2014 Post-Election Analysis: Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guns, Grass, and God's Wrath, Colorado's Budget, Politics, and Elections

Guns, Grass, and God’s Wrath, Colorado’s Budget, Politics, and Elections Michael J. Berry University of Colorado, Denver I. Introduction At the 2014 Democratic Party Assembly, incumbent Governor John Hickenlooper lamented that no “other state in the union . has been through as much as Colorado has in the past couple of years.” His statement was an implicit reference to a number of recent tragedies in the state. Among the most prominent were the 2012 Aurora movie theater shooting, the callous murder of Department of Corrections director Tom Clements in his home in early 2013, and the most dev- astating forest fires and floods to ever hit the state in June and September 2013. Hickenlooper’s statement on the uniqueness of the state, however, could just as easily apply to the state’s politi- cal realm. Colorado received considerable notoriety from the commencement of recreational marijuana sales on January 1, 2014. In a carefully staged photo opportunity, Iraq war veteran, Sean Azzariti, made the first legal recreational marijuana purchase as the state embarked on a grand social ex- periment. The prior year witnessed the first recall elections in state history resulting in the re- moval of two Democratic legislators from office including Senate President John Morse. An ad- ditional state senator facing a strong recall effort resigned under pressure. These highly charged campaigns to remove legislators were in response to the enactment of several controversial gun control laws. The legalization of recreational marijuana and the fight over gun control grabbed the lion’s share of headlines in the state over the past year. -

The Corrosive Effect of Recall Elections on State Legislative Politics Zachary J

86.1 SIEGEL_FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/14/2014 11:01 AM RECALL ME MAYBE? THE CORROSIVE EFFECT OF RECALL ELECTIONS ON STATE LEGISLATIVE POLITICS ZACHARY J. SIEGEL* For the first time in Colorado’s 137-year history, voters in two districts recalled their state senators from office in September 2013. Although the event prompted significant debate over the controversial gun legislation that sparked the grassroots efforts to trigger the recall elections, discussion generally overlooked the implications of using political recall altogether—implications that concern the very foundation of American democracy: the role of the legislator. This Comment aims to fill that gap, examining politically motivated recalls in the context of state legislatures. Using the recent Colorado examples as a case study, this Comment argues that increased use of the tactic will shake the foundation of state legislative politics. By forcing legislators to consider the chance that they might be recalled after voting on any controversial issue, the tactic upsets the delicate balance between a legislator’s ideal dual-role as a delegate and trustee, thereby distorting legislative decision- making. Additionally, increased use of political recall threatens to create a literal manifestation of the “permanent campaign,” and disproportionately advantage special interest and national groups in state politics. Seeking to address the problems associated with the increased use of this dangerous tactic, this Comment presents three policy recommendations. Two of the recommendations are aimed at preventing politically * J.D. Candidate, 2015, University of Colorado Law School; Executive Editor, University of Colorado Law Review. I would like to thank Carey DeGenaro, Elizabeth Sullivan, Cayla Crisp, Andrew Gomez, Cassady Adams, Alex Haynes, Shannon Kerr, Vanya Akraboff, and Vikrama Chandrashekar for their thoughtful edits. -

AURORASENTINEL.COM | 1 2 | AURORASENTINEL.COM | OCTOBER 13 - OCTOBER 19, 2016 Colorado Voters Have Plenty of Options on — and Leading up to — Election Day

OCTOBER 13 - OCTOBER 19, 2016 | AURORASENTINEL.COM | 1 2 | AURORASENTINEL.COM | OCTOBER 13 - OCTOBER 19, 2016 Colorado voters have plenty of options on — and leading up to — Election Day all inside. than 22 days before an election. candidate per race. If you select After last year’s successful Residents can register to vote multiple options, your vote in that ELECTION BY THE AURORA SENTINEL launch of mail ballots to all Colo- by appearing in-person at a voter race cannot be counted. INFORMATION ust when you thought every- rado residents, many of you read- service and polling center through • Do not draw or write outside • Mail-in ballots will be sent to thing had gone to pot with the ing this right now can start making Election Day. of the arrow, except to print the homes beginning Oct. 17. 2012 elections in Colorado, this those decisions sooner than later. Aurora is served by three coun- name of a write-in candidate. J • Election Day is Nov. 8. year’s General Election run-up — Voters statewide will start receiv- ties, and each county has slightly • Remember to sign your ballot especially at the top o’ the ticket ing mail ballots Oct. 17, and have different rules. envelope. Every signature will be • Voting service centers are — has had some moments even until Election Day, Nov. 8, to re- In Arapahoe County, general- compared to the voter’s registra- online for Arapahoe County smellier than the dankest, and now turn them or drop them in a local ly south of East Colfax Avenue, tion record, to ensure the correct at arapahoevotes.com and perfectly legal, Colorado cannabis. -

Chris Hansen, Gardner for Senate General Consultant Date: June 30, 2020 Re: Gardner Set to Face “Hot Mess” Hickenlooper in General Election ______

To: Interested Parties From: Chris Hansen, Gardner for Senate General Consultant Date: June 30, 2020 Re: Gardner set to face “hot mess” Hickenlooper in general election ____________________________________________________________________________ Today is Election Day in Colorado and Senator Cory Gardner will finally have an opponent. Although we fully expect John Hickenlooper to win tonight, he will emerge a bruised and battered candidate. His once-pristine reputation is tarnished. His glass jaw is fully exposed. And we haven't even started yet. John Hickenlooper is the worst candidate in the country One thing is clear, John Hickenlooper is the worst senate candidate in the country - in either party. Not counting his embarrassment of a presidential campaign, this primary was the first significant challenge in his political career and it was a complete disaster, requiring a multi-million dollar bailout in the form of a flood of last-minute ads from Chuck Schumer to prop him up. Just look at the last 30 days of headlines for Chuck Schumer’s number one recruit: ● AP NEWS: ‘A hot mess’: Hickenlooper stumbles into Democratic primary ● CO SUN: John Hickenlooper apologizes for 2014 “ancient slave ship” comment ● THE HILL: '#DropOutHick': Outcry from Indigenous women, allies over Hickenlooper in red face ● CPR: ‘Disrespect For The Rule Of Law’: Colorado Ethics Commission Holds Hickenlooper In Contempt For Skipping Hearing ● DENVER POST: John Hickenlooper violated ethics laws twice in 2018, commission finds ● CBS4 DENVER: Corporate Donations To Colorado Governor’s Office Raise ‘All Sorts Of Red Flags’ ● NPR: 1 Of Democrats' Top Senate Recruits Stumbles Amid Protests Recall that this primary was the easy path for Hickenlooper. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks at a Democratic

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks at a Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee Lunch in Denver, Colorado July 9, 2014 Thank you, everybody. Thank you. Thank you so much. Everybody, have a seat, have a seat. It is good to be back here. [Laughter] I love Colorado, love Denver. Everybody looks good in Denver too. [Laughter] I don't know what it is, the hair or sun, altitude? I don't know. [Laughter] It's just a bunch of good-looking people in Denver, Colorado. [Laughter] We've got some great friends here, and I just want to mention some of them. First of all, nobody has a bigger heart, nobody did better work on behalf of the natural resources of this amazing country of ours, nobody has been a better friend to me than the person who just introduced me. Love him dearly. We came into the Senate together, and our lives have crossed paths ever since, and I'm so very, very proud of him and Hope. So please give Ken Salazar a big round of applause. To Maggie Fox and Tess Udall, thank you for putting up with somebody in politics. [Laughter] That's always rough, but you do it with grace, and we're so grateful to you. To your wonderful former Governor, Bill Ritter, who continues to do great work on behalf of the environment. My dear friend, who was actually on the steering committee for my first race in '08, one of our national board members, Federico Peña, your former mayor. Somebody who helped begin the tradition of great Democratic Senators from Colorado, Gary Hart is here. -

Ova2011 REPORT to the COMMUNITY

2011 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY innovation “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.” – Steve Jobs Inspiring a Diverse Community of vision Leadership to Improve Colorado. Providing Content, Context and Access to Inspire Leaders to Engage in Issues mission Critical to the Region’s Success. · Cooperative, Collaborative Relationships · Inclusivity and Diversity of Perspective values · Dedication to Quality · Commitment to Volunteerism 2011 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY FROMTHECHAIRANDEXECUTIVEDIRECTOR November, 2011 The past year has been one of many accomplishments for the Denver Metro Chamber Leadership Foundation. As we reflected on 2010-2011, we noticed a thread that was woven throughout all of our programs—the thread of energetic innovation. The late Steve Jobs, former CEO and co- founder of Apple, is quoted as saying, “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.” In order for the Leadership Foundation to effectively carry out its mission of providing content, context and access to inspire leadership, it has made innovation a top priority, taking the initiative to introduce new programs, processes and content that broaden our perspective, provide an even stronger platform for dialogue and elevate our overall effectiveness at inspiring and educating our community’s leaders. One of the year’s brightest highlights was the launch of Colorado Experience’s pilot program. For many years, the Leadership Foundation has imagined bringing the Leadership Exchange program to a local level, and it was thanks to the strong support of our board of directors and hard work of the Colorado Experience committee that we made this vision into a reality with a trip to Colorado Springs. -

HOUSE JOURNAL SEVENTIETH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE of COLORADO First Regular Session

Page 1 HOUSE JOURNAL SEVENTIETH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE OF COLORADO First Regular Session First Legislative Day Wednesday, January 7, 2015 1 Prayer by the Reverend Felicia Smith-Graybeal, St. Bridget Episcopal 2 Church, Frederick. 3 4 The hour of ten o'clock having arrived, the House of Representatives of 5 the 70th General Assembly of the State of Colorado, pursuant to law, 6 was called to order by Mark Ferrandino, Speaker of the House of 7 Representatives, 69th General Assembly, State of Colorado. 8 9 Colors were posted by the Colorado Honor Guard 10 11 The National Anthem was sung by the University of Colorado Jazz 12 Ensemble 13 14 Pledge of Allegiance led by Student Leaders, Heather Elementary, 15 Frederick. 16 17 Speaker Mark Ferrandino announced that if there were no objections, 18 Marilyn Eddins would be appointed Temporary Chief Clerk. 19 ______________ 20 21 State of Colorado 22 Department of State 23 24 25 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) SS. CERTIFICATE 26 STATE OF COLORADO ) 27 28 I, Scott Gessler, Secretary of State of the State of Colorado, certify that 29 I have canvassed the "Abstract of Votes Cast" submitted in the State of 30 Colorado, and do state that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, the 31 attached list represents the total votes cast for the members of the 32 Colorado State House of Representatives for the 70th General Assembly 33 by the qualified electors of the State of Colorado in the November 4, 2014 34 General Election. 35 36 In testimony whereof I have set my hand and affixed the Great Seal of the 37 State of Colorado, at the City of Denver this tenth day of December, 38 2014. -

Senator Mark Udall (D) – First Term

CBHC Lunchtime Webinar – Preparing for the NCCBH Hill Day in Washington, D.C. June 2010 Working together to develop and deliver health resources to Colorado Communities Colorado Specifics • Colorado has almost 80 people attending this year • CBHC is scheduling meetings with all of the members of Congress on your behalf • CBHC will email virtual Hill Day packets this year to all registered participants – These will include individualized agenda’s for Hill Visits • Please register with the National Council on the website: http://www.thenationalcouncil.org/cs/join_us_in_2010 June 29th, 2010—Hyatt Regency Hotel • Opening Breakfast & Check-in-- 8:00-8:30 a.m. • Policy Committee Meeting Morning Session—8:30-11:45 • "National Council Policy Update" - Linda Rosenberg, President and CEO, National Council • "Implementing Healthcare Reform: New Payment Models" - Dale Jarvis, MCPP Consulting • Participant Briefing Lunch-12:00-1:00 p.m. • "The 2010 Elections Outlook" - Charlie Cook, The Cook Political Report--1:00-2:00 p.m. • "Healthcare Reform and the Medicaid Expansion" - Andy Schneider, House Committee on Energy & Commerce 2:00-3:00 p.m. June 29th Hyatt Regency • Public Policy Committee Meetings 3:15-5:00 p.m. Speakers for the afternoon session include: • "CMS Update" - Barbara Edwards, Director, Disabled and Elderly Health Programs Group, Center for Medicaid, CHIP, and Survey and Certification (CMCS), CMS • "Parity Implementation - What You Should Know and Do" - Carol McDaid, Capitol Decisions, Parity Implementation Coalition June 29—Break Out -

Office of Government Relations Annual Report 2016

Office of Government Relations Annual Report 2016 Table of Contents Page Office of Government Relations Overview 2 Office of Government Relations Contacts 3 State Relations ♦ CU Initiated Legislation 4 ♦ Key Higher Education Legislation 5 ♦ Key Health Care Legislation 9 ♦ Other Legislation 12 Federal Relations ♦ Key Research Legislation 15 ♦ Key Health Care Legislation 68 ♦ Key Education Legislation 70 ♦ Key Immigration Legislation 73 State and Federal Meetings, Events and Tours 74 Office of Government Relations Team 81 OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT RELATIONS Overview This annual report covers work by the Office of Government Relations from January 1 – December 31, 2016. Mission The mission of the Office of Government Relations is to support the University of Colorado by building effective partnerships between the University and state and federal governments. This is achieved through representation and advocacy of CU’s needs and interests with state and federal elected officials in Colorado and Washington, D.C. Goals • Promote the University’s interests at the state and federal level. • Enhance the understanding of the role and value of CU. • Achieve status as one of the top public university governmental relations offices in the United States. Strategies 1) Maintain visibility at both the state and federal level through testimony, tours, outreach events, Hill visits, and other activities to increase contact with state and federal policy makers. 2) Foster relationships between the president, chancellors and designated officers of the university with members of the General Assembly, Colorado Congressional Delegation, and Executive branch of both the state and federal government. 3) Engage the business community, CU Advocates, and alumni to help advocate for the university’s initiatives. -

Congressional District 7 This Page Includes All of the State Legislative Districts That Are Within, Or Partially Within, Congressional District 7

2016 Ballot Buddy - Congressional District 7 This page includes all of the state legislative districts that are within, or partially within, Congressional District 7. Candidates that CVA has endorsed are designated in the right-hand column as a "Pro-Animal Pick." We may not make an endorsement in every race. Our endorsements are non-partisan and are based solely on the candidate’s stance on animal issues. We consider questionnaire responses and voting history. Other candidates may earn a "Paws Down" for their history of sponsoring anti-animal bills or working against humane legislation. Office Sought and Candidates Incumbent V oting Record (last 6 years): Questionnaire listed in party order (may be for different offices) Notes Score Name Party 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 U.S. Senate Michael Bennet DEM 42% 50% 57% (so far) Darryl Glenn REP Lily Tang Williams LIB Arn Menconi GRN Bill Hammons UNI Paul Noel Fiorino U Dan Chapin U Don Willoughby (write-in) U U.S. Representative - Congressional District 7 Ed Perlmutter DEM 54% 66% 78% (so far) George Athanasopoulos REP Martin L. Buchanan LIB (Congressional scores compiled by the Humane Society Legislative Fund) Colorado State Senate - Senate District 19 Rachel Zenzinger DEM 100% A 100% Pro-Animal Pick! Laura J. Woods REP 67% C+ 0% F No Response Colorado State Senate - Senate District 21 Dominick Moreno DEM 100% A- 100% A- 100% A- 100% A- 80% Pro-Animal Pick! Kara Leach Palfy REP 70% Colorado State Senate - Senate District 25 Jenise May DEM 100% A- 100% A- 80% Pro-Animal Pick! Kevin Priola REP -

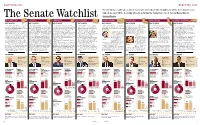

The 2010 Senate Landscape Is Almost Evenly Split Down The

ELECTION 2010 ELECTION 2010 The 2010 Senate landscape is almost evenly split down the middle: Republicans will be defending 18 seats, while Democrats will be defending 19 seats, including the January special election in Massachusetts. The Senate Watchlist BY CHARLES MAHTESIAN CONNECTICUT NEVada ARKANSAS COLORADO PENNSYLVANIA LOUISIANA CALIFORNIA NORTH CAROLINA WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH Chris Dodd, a five-term Democrat, is arguably The only thing stopping Senate Majority Leader In a state where John McCain crushed Barack Democrat Michael Bennet, appointed Democratic Sen. Arlen Specter faces what may Just when it looked like GOP Sen. David Democratic Sen. Barbara Boxer won a There’s no scandal or silver-bullet issue. He’s the party’s most vulnerable Senate incumbent — Harry Reid from being rated as the most vulnerable Obama by 20 points in 2008 and where polls show to the Senate seat left vacant when Ken be the toughest election of his Senate career, Vitter might weather the scandal surrounding second term in 1998 by 10 percentage points reasonably well-funded. And unlike former GOP just look at the lengthy list of Republicans who are Democratic senator is the quality of his opposition. voters are deeply skeptical of Obama’s health care Salazar became interior secretary, has two which is saying something given the long arc of his the revelation that he was a client of a and a third in 2004 by 20 points. colleague Sen. Elizabeth Dole, who lost by a champing at the bit to take him on. -

Nnual Report 16 a 2016 $122.7 11,945 Colorado Million Sbdc Totals $95.9 1 = $1,000,000 1 = 100 1 = 50 Compared to 2015 Million $88.7 Million 6,233 3,771 3,094

’ NNUAL REPORT 16 A 2016 $122.7 11,945 COLORADO MILLION SBDC TOTALS $95.9 1 = $1,000,000 1 = 100 1 = 50 COMPARED TO 2015 MILLION $88.7 MILLION 6,233 3,771 3,094 451 CAPITAL SALES CLIENTS TRAINING JOBS JOBS NEW FORMATION INCREASE CONTRACTS CONNECTED ATTENDEES CREATED RETAINED BUSINESSES WHAT IS THE ABOUT THIS REPORT COLORADO SBDC? The Colorado Small Business Development Center Network’s 2016 annual report The Colorado Small Business Development Center (SBDC) Network is dedicated to highlights the cooperation among community organizations that support small helping existing and new businesses grow and prosper in Colorado by providing free, businesses. Academic institutions, economic development organizations and local confidential consulting and no- or low-cost training programs and workshops. The governments, as well as corporate partners, all play a part in the success of the SBDC. SBDC strives to be the premier, trusted choice of Colorado businesses for consulting, The participation of these entities is crucial to the support given to businesses around training and resources. the state. participation of these entities is crucial to the The sbdc is dedicated to helping small and mid-sized businesses throughout the state achieve their goals. support given to businesses around the state. This report contains success stories of SBDC clients from across the state, as well The SBDC is dedicated to helping small and mid-sized businesses throughout the as financial impact numbers, all organized by center and congressional district. state achieve their goals of growth, expansion, innovation, increased productivity, management improvement and overall success. The network combines the resources As a result of its one-on-one consulting and free or low-cost training programs, the of federal, state and local organizations with those of the educational system and Colorado SBDC was able to assist in the generation of $19.58 in capital formation for private sector to meet the specialized and complex needs of the small business every federal grant dollar obtained by the state.