UGANDA: Skills to Support the Transport Public Disclosure Authorized and Logistics Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of Uganda (Ministry of Works And

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA (MINISTRY OF WORKS AND TRANSPORT COMPONENT) IDA CREDIT NO.4147 UG REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE EAST AFRICA TRADE AND TRANSPORT FACILITATION PROJECT (EATTFP) FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 2015 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2015 ...................................................................................................................... iv REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE SPECIAL ACCOUNT OPERATIONS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2015 ........................................................................................................... vi 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 3.0 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND COMPONENTS .......................................................................... 1 4.0 AUDIT OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. 2 5.0 AUDIT PROCEDURES PERFORMED ........................................................................................ 3 6.0 CATEGORIZATION AND SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................................................... 4 6.2 Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................... -

COVID-19 Interventions Report Financial Year 2019/20

COVID-19 Interventions Report Financial Year 2019/20 October 2020 Budget Monitoring and Accountability Unit (BMAU) Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Sector Performance .............................................................................................................. 2 2.1Agriculture Sector ............................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Education and Sports Sector ............................................................................................ 2 2.3 Health Sector .................................................................................................................... 7 2.3.1 Financial Performance................................................................................................... 7 2.3.2 Overall performance ...................................................................................................... 9 2.3.3 Detailed Performance by output for GoU Support........................................................ 9 2.3.4 Contingency Emergency Response Component (CERC) towards COVID-19 by the World Bank .......................................................................................................................... -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

The Informal Cross Border Trade Qualitative Baseline Study 2008 Uganda Bureau of Statistics

UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS THE INFORMAL CROSS BORDER TRADE QUALIT ATIVE BASELINE STUDY 2008 February 2009 FOREWORD The Qualitative Module of the Informal Cross Border Trade (ICBT) Survey is the first comprehensive Study of its kind to be conducted in Uganda to bridge information gaps regarding informal trade environment. The study was carried out at Busia, Mirama Hills, Mpondwe and Mutukula border posts. The ICBT Qualitative study collected information on informal trade environment and the constraints traders’ experience in order to guide policy formulation, planning and decision making in the informal cross border sub-sector. The study focused specifically on gender roles in ICBT, access to financial services, marketing information, food security, and tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade among others. This study was conducted alongside the ICBT Quantitative Module that collected information on the nature of products transacted, their volumes and value, and, the direction of trade. Notwithstanding the significant contribution informal cross border trade has made to the welfare of the people of the East African region (in terms of employment creation, economic empowerment of women, food security, regional and social integration), there are no appropriate policies designed to guide players in the informal trade sector. The information gathered, therefore, will provide an insight into the challenges informal traders face in their day to day business and will guide policy and decision makers to enact appropriate policies to harness the potential benefits of informal cross border trade. The Bureau is grateful to the Integrated Framework (IF) through TRACE Project of the Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Industry for the financial contribution that facilitated the study. -

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll Free Line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @Urapage Twitter: @Urauganda

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll free line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @URApage Twitter: @URAuganda CENTRAL REGION ( Kampala, Wakiso, Entebbe, Mukono) s/n Station Location Tax Heads URA Head URA Tower , plot M 193/4 Nakawa Industrial Ara, 1 Domestic Taxes/Customs Office P.O. Box 7279, Kampala 2 Katwe Branch Finance Trust Bank, Plot No 115 & 121. Domestic Taxes 3 Bwaise Branch Diamond Trust Bank,Bombo Road Domestic Taxes 4 William Street Post Bank, Plot 68/70 Domestic Taxes Nakivubo 5 Diamond Trust Bank,Ham Shopping Domestic Taxes Branch United Bank of Africa- Aponye Hotel Building Plot 6 William Street Domestic Taxes 17 7 Kampala Road Diamond Trust Building opposite Cham Towers Domestic Taxes 8 Mukono Mukono T.C Domestic Taxes 9 Entebbe Entebbe Kitooro Domestic Taxes 10 Entebbe Entebbe Arrivals section, Airport Customs Nansana T.C, Katonda ya bigera House Block 203 11 Nansana Domestic Taxes Nansana Hoima road Plot 125; Next to new police station 12 Natete Domestic Taxes Natete Birus Mall Plot 1667; KyaliwajalaNamugongoKira Road - 13 Kyaliwajala Domestic Taxes Martyrs Mall. NORTHERN REGION ( East Nile and West Nile) s/n Station Location Tax Heads 1 Vurra Vurra (UG/DRC-Border) Customs 2 Pakwach Pakwach TC Customs 3 Goli Goli (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 4 Padea Padea (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 5 Lia Lia (UG/DRC - Border) Customs 6 Oraba Oraba (UG/S Sudan-Border) Customs 7 Afogi Afogi (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 8 Elegu Elegu (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 9 Madi-opei Kitgum S/Sudan - Border Customs 10 Kamdini Corner -

Mogondo Julius Wondero EOEIYE

d/ TELEPHONES: 04L434OLO0l4340LL2 Minister of State for East E.MAIL: [email protected] African Community Affairs TELEFAX: o4t4-348r7t 1't Floor, Postal Building Yusuf Lule Road ln any correspondence on this subject P.O. Box 7343, Kampala please quote No: ADM 542/583/01 UGANDA rHE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 22"4 August,2Ol9 FTHES P ( L \-, 4 Hon. Oumo George Abott U Choirperson, Committee for 2019 * 2 3 AUG s Eost Africon Community Affoirs Porlioment of Ugondo EOEIYE L t4 raE \, \, KAMPATA NT OF CLOSURE OF UGANDA.RWANDA BORDERS Reference is mode to letter AB: I 171287 /01 doted l5rn August,20l9 oddressed to the Minister of Eost Africon Community Affoirs ond copied to the Permonent Secretory, Ministry of Eost Africon Community Affoirs regording the obove subject motter. ln the letter, you invited the Ministry to updote the EAC Committee on the progress mode to hondle the Closure of Ugondo-Rwondo Borders on Ihursdoy,29r,August, 2019 at 10.00om. As stoted this discussion would help ensure thot the Eost Africon Common Morket Protocol is effectively implemented for the benefit of Ugondo ond other Portner Stofes. The Purpose of this letter therefore, is to forword to you o Report on the Stotus of the obove issue for further guidonce during our interoction with the committee ond to re-offirm our ottendonce os per the stipuloted dote ond time Mogondo Julius Wondero MINISTER OF STATE FOR EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS C.C. The Speoker, Porlioment of Ugondo, Kompolo The Clerk to Porlioment, Porlioment of Ugondo, Kompolo Permonent Secretory, Ministry of Eost Africon Community Affoirs MINISTRY OF EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS REPORT ON THE CLOSURE OF UGANDA. -

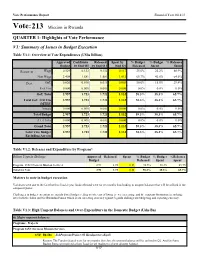

Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda QUARTER 1: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q1 by End Q 1 End Q1 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 0.529 0.132 0.132 0.117 25.0% 22.2% 88.9% Non Wage 2.408 1.581 1.581 1.012 65.7% 42.0% 64.0% Devt. GoU 0.020 0.010 0.010 0.003 50.0% 15.0% 29.4% Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total GoU+Ext Fin 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% (MTEF) Arrears 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Total Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% A.I.A Total 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Grand Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total Vote Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1652 Overseas Mission Services 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total for Vote 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Matters to note in budget execution Variances were due to the fact that this finacial year funds released were for six months thus leading to unspent balances that will be utilised in the subquent Quater. -

Bmau Briefing Paper (15/18) May2018

BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (15/18) MAY 2018 Achievement of the NDPII targets for national roads. Is the Uganda National Roads Authority on track? Overview Key Issues The Government of Uganda (GoU) is implementing i) Budget allocation to the sector has the second National Development Plan (NDP II, persistently fallen short of the NDPII FY2015/16 – FY2019/20). This plan recognises projections. Worse still, not all infrastructure as one of the development appropriated funds are released. fundamentals required to attain middle income status target by 2040. The NDPII has four objectives but ii) More than 100 projects are earmarked the one directly applicable to the roads sub-sector is: under UNRA for implementation within increasing the stock and quality of strategic the NDPII period, but over 60% of the infrastructure to accelerate the country’s these are still at either design and competitiveness. procurement stages, so UNRA is unlikely As a result, a sizeable share of commitments are to achieve the NDPII targets. being directed to infrastructure investments with a iii) Allocations of resources between focus on reducing travel times between regions, new road development projects and integrating the national market and connecting it to maintenance is at a ratio of 80:20% hence other markets in the East African Community. creating a maintenance backlog. This briefing paper assesses the extent to which Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) is achieving the national roads NDPII targets over time. Introduction of paved and unpaved roads. The network also comprises of 10 ferries located at The Uganda National Roads Authority strategic points that link national roads (UNRA) aims to develop and maintain a across major water bodies. -

Background to the Budget Background to the Budget

BACKGROUND TO THE BUDGET 2015/16 FISCAL YEAR Maintaining Infrastructure Investment and Promoting Excellence in Public Service Delivery Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development BACKGROUND TO THE BUDGET 2015/16 FISCAL YEAR Maintaining Infrastructure Investment and Promoting Excellence in Public Service Delivery Maintaining Infrastructure Investment and Promoting Excellence in Public Service Delivery BACKGROUND TO THE BUDGET 2015/16 FISCAL YEAR able of Contents TChapter 1 : INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................1 Chapter 2 : GLOBAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENTS AND PROSPECTS .................4 2.1 Global Economic Developments and Prospects .........................................................4 2.1.1 Global Economic Growth ..............................................................................4 2.1.2 World Commodity Prices and Inflation ..........................................................5 2.1.3 International Trade .......................................................................................6 2.1.4 International Finance for Development ..........................................................7 2.2 Regional Economic Developments and Prospects .................................................8 2.2.1 Sub Saharan Africa .......................................................................................8 2.2.2 The East African Community and South Sudan ...........................................9 Chapter 3 : REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT -

Health Sector Annual Budget Monitoring Report FY2019/20

Health SECtor ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug Health Sector : Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2019/20 A HEALTH SECtor ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................................................... iii FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Scope ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 Sampling ..................................................................................................................................... -

Uganda UNHCR Presence and Refugee Locations As of 18 Oct 2018

Uganda UNHCR Presence and refugee locations as of 18 Oct 2018 SOUTH SUDAN Madi-Opei Angilia Aweno-Olwiyo Afoji Ngomoromo Busia Moyo Kaabong ± Sub Office Moyo Waligo Madi Opei CP Oraba Sub Office Yumbe Elegu Lokung CP Yumbe Lamwo Lobule Bidibidi Palabek Kitgum Koboko Field Office Lamwo Imvepi Maracha Sub Office Ocea RC Adjumani Arua Amuru Kotido Gulu Arua Pader Agago Moroto Omoro Abim Nwoya Zombo Pakwach Otuke Nebbi Napak Kole Oyam Kapelebyong DEMOCRATIC Lira Alebtong REPUBLIC Kiryandongo Amuria OF THE CONGO Nabilatuk Buliisa Field Unit Kiryandongo Apac Kwania Dokolo Katakwi Kiryandongo rt Amudat e Soroti Nakapiripirit lb Masindi A ke Kaberamaido a Hoima L. Bisina L Amolatar Ngora Bulambuli Sebagoro Sub Office Hoima Lake Kyoga Serere Kumi Nakasongola Kween Bukedea Kikuube Kapchorwa Nsonga Field Unit Kyangwali Bukwo Buyende Pallisa Kyangwali Kyankwanzi Butebo Budiba Makindo Sironko Kagoma RC Nakaseke Budaka Rwebisengo Ntoroko Kaliro Kibuku Mbale Kagadi V Bududa i Kakumiro c t o Namisindwa Nyankanda r Kamuli Kayunga i Namutumba a Butaleja Luwero Bundibugyo Kiboga N Iganga i Kibaale l Manafwa Butogo Bubukwanga TC e Kyenjojo Luuka Kasiri Kabarole Tororo Busunga Mubende Bugweri Bulyantano Kyegegwa Jinja Kassanda Bugiri Bunyangabu Mityana Field Unit Rwamwanja Field Unit Kyaka II Branch Office Kampala KENYA Mahani RC Sweswe RC Buikwe Busia Kyaka II Mayuge Kamwenge Rwamwanja Kampala Gomba Butambala Kasese Lake Mpondwe Ssembabule George Mpigi Wakiso Mukono Kalungu Namayingo Ibanda Kiruhura Lyantonde Bukomansimbi Rubirizi Buhweju Lake Buvuma Lwengo -

PAR RSSP3 Nyakahita

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP MULTINATIONAL BUSEGA-MPIGI AND KAGITUMBA-KAYONZA-RUSUMO ROADS PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT OITC DEPARTMENT May 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms & Abbreviations i Loan Information ii Project Summary iv Result-Based Logical Frameworks vi Project Timeframe viii I. STRATEGIC THRUST AND RATIONALE 1 1.1 Project Linkages with Country Strategy and Objectives 1 1.2 Rationale for Bank’s Involvement 1 1.3 Donors Coordination 2 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2 2.1 Project Objectives 3 2.2 Project Components 4 2.3 Technical Solution Retained and Other Alternatives Explored 4 2.4 Project Type 4 2.5 Project Cost and Financing Arrangements 4 2.6 Project’s Target Area and Population 5 2.7 Participatory Processes for Project Identification, Design and Implementation 6 2.8 Bank Group Experiences and Lessons Reflected in Project Design 6 2.9 Key Performance Indicators 7 III. PROJECT FEASIBILITY 7 3.1 Economic and Financial Performance 7 3.2 Environmental and Social Impacts 8 IV. IMPLEMENTATION 11 4.1 Implementation Arrangements 11 4.2 Monitoring 13 4.3 Governance 13 4.4 Sustainability 14 4.5 Risk Management 16 4.6 Knowledge Building 16 V: LEGAL INSTRUMENTS AND AUTHORITY 16 5.1 Legal Instrument 16 5.2 Conditions Associated with Bank’s Intervention 16 5.3 Compliance with Bank Policies 17 VI. RECOMMENDATION 17 Appendices I. Country’s Comparative Socio-Economic Indicators I II. Table of ADB’s Portfolio in Uganda and Rwanda III III. Key Related Projects Financed by the Bank and Other Development Partners in Uganda V and Rwanda IV. Map of the Project Area VII V.