A Scoping Study of Illicit Financial Flows Impacting Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of Uganda (Ministry of Works And

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA (MINISTRY OF WORKS AND TRANSPORT COMPONENT) IDA CREDIT NO.4147 UG REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE EAST AFRICA TRADE AND TRANSPORT FACILITATION PROJECT (EATTFP) FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 2015 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2015 ...................................................................................................................... iv REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE SPECIAL ACCOUNT OPERATIONS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2015 ........................................................................................................... vi 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 3.0 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND COMPONENTS .......................................................................... 1 4.0 AUDIT OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. 2 5.0 AUDIT PROCEDURES PERFORMED ........................................................................................ 3 6.0 CATEGORIZATION AND SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................................................... 4 6.2 Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................... -

Distribution, Utilization and Management of the Extra-Limital Common Warthog (Phacochoerus Africanus) in South Africa

Distribution, utilization and management of the extra-limital common warthog (Phacochoerus africanus) in South Africa Monlee Swanepoel Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Conservation Ecology and Entomology) in the Faculty of AgriSciences, Stellenbosch University Promoter: Prof Louwrens C. Hoffman Co-Promoter: Dr. Alison J. Leslie March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to the following persons and institutions: My supervisors, Dr. Alison J. Leslie and Prof. Louwrens C. Hoffman for invaluable assistance, expertise, contribution and support and patience. The Meat Science team of Department of Animal Sciences at Stellenbosch University, including the technical and support staff for their extensive assistance, support and encouragement Academics, staff and colleagues of this institution and others for their contribution and assistance. An especial thank you to Prof. Martin Kidd, Marieta van der Rijst, Nina Muller, Erika Moelich, Lisa Uys, Gail Jordaan, Greta Geldenhuys, Michael Mlambo, Janine Booyse, Cheryl Muller, John Achilles, Dr. -

COVID-19 Interventions Report Financial Year 2019/20

COVID-19 Interventions Report Financial Year 2019/20 October 2020 Budget Monitoring and Accountability Unit (BMAU) Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Sector Performance .............................................................................................................. 2 2.1Agriculture Sector ............................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Education and Sports Sector ............................................................................................ 2 2.3 Health Sector .................................................................................................................... 7 2.3.1 Financial Performance................................................................................................... 7 2.3.2 Overall performance ...................................................................................................... 9 2.3.3 Detailed Performance by output for GoU Support........................................................ 9 2.3.4 Contingency Emergency Response Component (CERC) towards COVID-19 by the World Bank .......................................................................................................................... -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

The Informal Cross Border Trade Qualitative Baseline Study 2008 Uganda Bureau of Statistics

UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS THE INFORMAL CROSS BORDER TRADE QUALIT ATIVE BASELINE STUDY 2008 February 2009 FOREWORD The Qualitative Module of the Informal Cross Border Trade (ICBT) Survey is the first comprehensive Study of its kind to be conducted in Uganda to bridge information gaps regarding informal trade environment. The study was carried out at Busia, Mirama Hills, Mpondwe and Mutukula border posts. The ICBT Qualitative study collected information on informal trade environment and the constraints traders’ experience in order to guide policy formulation, planning and decision making in the informal cross border sub-sector. The study focused specifically on gender roles in ICBT, access to financial services, marketing information, food security, and tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade among others. This study was conducted alongside the ICBT Quantitative Module that collected information on the nature of products transacted, their volumes and value, and, the direction of trade. Notwithstanding the significant contribution informal cross border trade has made to the welfare of the people of the East African region (in terms of employment creation, economic empowerment of women, food security, regional and social integration), there are no appropriate policies designed to guide players in the informal trade sector. The information gathered, therefore, will provide an insight into the challenges informal traders face in their day to day business and will guide policy and decision makers to enact appropriate policies to harness the potential benefits of informal cross border trade. The Bureau is grateful to the Integrated Framework (IF) through TRACE Project of the Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Industry for the financial contribution that facilitated the study. -

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll Free Line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @Urapage Twitter: @Urauganda

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll free line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @URApage Twitter: @URAuganda CENTRAL REGION ( Kampala, Wakiso, Entebbe, Mukono) s/n Station Location Tax Heads URA Head URA Tower , plot M 193/4 Nakawa Industrial Ara, 1 Domestic Taxes/Customs Office P.O. Box 7279, Kampala 2 Katwe Branch Finance Trust Bank, Plot No 115 & 121. Domestic Taxes 3 Bwaise Branch Diamond Trust Bank,Bombo Road Domestic Taxes 4 William Street Post Bank, Plot 68/70 Domestic Taxes Nakivubo 5 Diamond Trust Bank,Ham Shopping Domestic Taxes Branch United Bank of Africa- Aponye Hotel Building Plot 6 William Street Domestic Taxes 17 7 Kampala Road Diamond Trust Building opposite Cham Towers Domestic Taxes 8 Mukono Mukono T.C Domestic Taxes 9 Entebbe Entebbe Kitooro Domestic Taxes 10 Entebbe Entebbe Arrivals section, Airport Customs Nansana T.C, Katonda ya bigera House Block 203 11 Nansana Domestic Taxes Nansana Hoima road Plot 125; Next to new police station 12 Natete Domestic Taxes Natete Birus Mall Plot 1667; KyaliwajalaNamugongoKira Road - 13 Kyaliwajala Domestic Taxes Martyrs Mall. NORTHERN REGION ( East Nile and West Nile) s/n Station Location Tax Heads 1 Vurra Vurra (UG/DRC-Border) Customs 2 Pakwach Pakwach TC Customs 3 Goli Goli (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 4 Padea Padea (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 5 Lia Lia (UG/DRC - Border) Customs 6 Oraba Oraba (UG/S Sudan-Border) Customs 7 Afogi Afogi (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 8 Elegu Elegu (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 9 Madi-opei Kitgum S/Sudan - Border Customs 10 Kamdini Corner -

African Studies Abstracts Online: Number 52, 2015

Number 52, 2015 AFRICAN STUDIES ABSTRACTS ONLINE Number 52, 2015 Contents Editorial policy .......................................................................................................... iii Geographical index.................................................................................................... 1 Subject index ............................................................................................................. 3 Author index .............................................................................................................. 6 Periodicals abstracted in this issue .......................................................................... 13 Abstracts ................................................................................................................. 16 Abstracts produced by Ursula Oberst, Katrien Polman, Angela Robson, Germa Seuren, Heleen Smits i ii EDITORIAL POLICY EDITORIAL POLICY African Studies Abstracts Online is published quarterly and provides an overview of journal articles and edited works on sub-Saharan Africa in the field of the social sciences and the humanities. All publications are available in the library of the African Studies Centre in Leiden, The Netherlands. Many are accessible full text in the library's online catalogue at catalogue.ascleiden.nl. Clicking on the title of an article or edited work in ASA Online brings you via the ASCLink to the full text if available (subject to access restrictions). Coverage ASA Online covers edited works (up to 50 in each issue) -

Mogondo Julius Wondero EOEIYE

d/ TELEPHONES: 04L434OLO0l4340LL2 Minister of State for East E.MAIL: [email protected] African Community Affairs TELEFAX: o4t4-348r7t 1't Floor, Postal Building Yusuf Lule Road ln any correspondence on this subject P.O. Box 7343, Kampala please quote No: ADM 542/583/01 UGANDA rHE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 22"4 August,2Ol9 FTHES P ( L \-, 4 Hon. Oumo George Abott U Choirperson, Committee for 2019 * 2 3 AUG s Eost Africon Community Affoirs Porlioment of Ugondo EOEIYE L t4 raE \, \, KAMPATA NT OF CLOSURE OF UGANDA.RWANDA BORDERS Reference is mode to letter AB: I 171287 /01 doted l5rn August,20l9 oddressed to the Minister of Eost Africon Community Affoirs ond copied to the Permonent Secretory, Ministry of Eost Africon Community Affoirs regording the obove subject motter. ln the letter, you invited the Ministry to updote the EAC Committee on the progress mode to hondle the Closure of Ugondo-Rwondo Borders on Ihursdoy,29r,August, 2019 at 10.00om. As stoted this discussion would help ensure thot the Eost Africon Common Morket Protocol is effectively implemented for the benefit of Ugondo ond other Portner Stofes. The Purpose of this letter therefore, is to forword to you o Report on the Stotus of the obove issue for further guidonce during our interoction with the committee ond to re-offirm our ottendonce os per the stipuloted dote ond time Mogondo Julius Wondero MINISTER OF STATE FOR EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS C.C. The Speoker, Porlioment of Ugondo, Kompolo The Clerk to Porlioment, Porlioment of Ugondo, Kompolo Permonent Secretory, Ministry of Eost Africon Community Affoirs MINISTRY OF EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS REPORT ON THE CLOSURE OF UGANDA. -

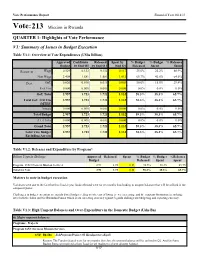

Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda QUARTER 1: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q1 by End Q 1 End Q1 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 0.529 0.132 0.132 0.117 25.0% 22.2% 88.9% Non Wage 2.408 1.581 1.581 1.012 65.7% 42.0% 64.0% Devt. GoU 0.020 0.010 0.010 0.003 50.0% 15.0% 29.4% Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total GoU+Ext Fin 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% (MTEF) Arrears 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Total Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% A.I.A Total 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Grand Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total Vote Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1652 Overseas Mission Services 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total for Vote 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Matters to note in budget execution Variances were due to the fact that this finacial year funds released were for six months thus leading to unspent balances that will be utilised in the subquent Quater. -

National Sports Calendar for the Financial Year 2019

NATIONAL SPORTS CALENDAR FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/2020 DATE ACTIVITY SPORT VENUE JULY 2019 TBC Ssesse Islands Cycling Tour Cycling Kalangala TBC Buganda cup Basketball tournament for High Schools (Regional) Basketball High schools in Buganda region 1st National Beach Volleyball Championship Volleyball Lido Beach 3rd -14th World Volley ball University Games Volleyball TBC Naples, Italy. 4th -7th Seals Invitational Swimming Gala at Kampala Parents Swimming Kampala Parents School 4th 7th Ivory Coast Badminton International Tournament Badminton Ivory coast 5th -7th National Zurkaneh Championship for all African games. Zurkaneh Kampala- Uganda 6th Ranking for Pro-Arm Kick Boxing 2nd Season Kickboxing Freedom City 6th S1 and S2 National Woodball championships WoodBall London College Nansana 6th 3rd FINA Swimming World Aquatics Day Celebrations Swimming TBD 6th Kyabazinga Athletics Championships/ Kids Athletics Athletics Iganga 6th Western Region Athletics Championships/ Kids Athletics Athletics Mbarara 6th -14th National Hockey League Hockey Lugogo 6th -7th YMCA Darts Sports Gala Singles(Men & Women) Darts Kalanamo 7th -8th National Volleyball League Volleyball UCU/ MUBS/ LUGOGO 7th Dolphins Fast and Furious 2019 clubs Swimming Gala at Gems Cambridge Swimming Gems Cambridge International School International School 7th -14th National Sec. School Netball Championship Netball Teso College Aloet 8th -14th Uganda Secondary Schools Athletics Championship Athletics Soroti/ Tororo 11th -12th Rowing World Cup III Rowing Rotterdam 12th – 14th Mayeku -

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

Uganda's Economic Development

CHECK REALITY UGANDA’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF CLIMATE CHANGE Emmanuel Kasimbazi This project is funded by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Uganda Plot 51 A, Prince Charles Drive, Kololo, P.O. Box 647 Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256 - (0)312 - 262011/2 www.kas.de/Uganda Uganda’s Economic Development REALITY CHECK UGANDA’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF CLIMATE CHANGE Emmanuel Kasimbazi The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung but rather those of the author. i REALITY CHECK UGANDA’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF CLIMATE CHANGE Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Uganda Programme 51A, Prince Charles Drive, Kololo P.O. Box 647, Kampala Tel: +256 - (0)312 - 262011/2 www.kas.de/uganda ISBN: 978 9970 477 00 5 Author: Dr. Emmanuel Kasimbazi Design and Production Media PH Limited Plot 4 Pilkington Road Tel: +256 (0) 312 371217 Email: [email protected] © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without written permission of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..................................................................... v FOREWORD .................................................................................. vi LIST OF FIGURES AND PHOTOS .................................................. viii LIST OF TABLES .........................................................................