Paper Optics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typography One Typeface Classification Why Classify?

Typography One typeface classification Why classify? Classification helps us describe and navigate type choices Typeface classification helps to: 1. sort type (scholars, historians, type manufacturers), 2. reference type (educators, students, designers, scholars) Approximately 250,000 digital typefaces are available today— Even with excellent search engines, a common system of description is a big help! classification systems Many systems have been proposed Francis Thibaudeau, 1921 Maximillian Vox, 1952 Vox-ATypI, 1962 Aldo Novarese, 1964 Alexander Lawson, 1966 Blackletter Venetian French Dutch-English Transitional Modern Sans Serif Square Serif Script-Cursive Decorative J. Ben Lieberman, 1967 Marcel Janco, 1978 Ellen Lupton, 2004 The classification system you will learn is a combination of Lawson’s and Lupton’s systems Black Letter Old Style serif Transitional serif Modern Style serif Script Cursive Slab Serif Geometric Sans Grotesque Sans Humanist Sans Display & Decorative basic characteristics + stress + serifs (or lack thereof) + shape stress: where the thinnest parts of a letter fall diagonal stress vertical stress no stress horizontal stress Old Style serif Transitional serif or Slab Serif or or reverse stress (Centaur) Modern Style serif Sans Serif Display & Decorative (Baskerville) (Helvetica) (Edmunds) serif types bracketed serifs unbracketed serifs slab serifs no serif Old Style Serif and Modern Style Serif Slab Serif or Square Serif Sans Serif Transitional Serif (Bodoni) or Egyptian (Helvetica) (Baskerville) (Rockwell/Clarendon) shape Geometric Sans Serif Grotesk Sans Serif Humanist Sans Serif (Futura) (Helvetica) (Gill Sans) Geometric sans are based on basic Grotesk sans look precisely drawn. Humanist sans are based on shapes like circles, triangles, and They have have uniform, human writing. -

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at Totaling 350 Font Families with a Total of 1357 Font Styles

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/bitstream totaling 350 font families with a total of 1357 font styles The former Bitstream typeface libraries consisted mainly of forgeries of Linotype fonts and of ITC fonts. See the list below on the pages 24–29 about the old Bitstream Typeface Library of 1992. The 2005 Bitstream typeface library contains the same forgeries of Linotype fonts as formerly and also the same ITC fonts, but it also includes a lot of new mediocre „rubbish fonts“ (e.g. „Alphabet Soup“, „Arkeo“, „Big Limbo“), but also a few new quality fonts (e.g. „Drescher Grotesk“, „Prima Serif“ etc.). On the other hand, a few old fonts (e.g. „Caxton“) were removed. See the list below on pages 1–23. The typeface collection of CorelDraw comprises almost the entire former old Bitstream typeface library (see the list below on pages 24–29) with the following exceptions: 1. A few (ca. 3) forgeries of Linotype fonts are missing in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. the fonts „Baskerville No. 2“ (= Linotype Baskerville No. 2), „Italian Garamond“ (= Linotype Garamond Simoncini), and „Revival 555“ (= Linotype Horley Old Style). 2. A lot (ca. 11) of ITC fonts are not contained in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. „ITC Berkeley Oldstyle“, „ITC Century“, „ITC Clearface“, „ITC Isbell“, „ITC Italia“, „ITC Modern No. 216“, „ITC Ronda“, „ITC Serif Gothic“, „ITC Tom’s Roman“, „ITC Zapf Book“, and „ITC Zapf International“. Ulrich Stiehl, Heidelberg 3-May 2005 Aachen – 2 styles Ad Lib™ – 1 styles Aerospace Pi – 1 styles Aldine -

Afgbaskerville (The Type Face)

gfaBaskerville (the type face) xagfi {the type} {the man} abcdefghijklmn opqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHI JKLMNOPQR STUVWXYZ Having been an early admirer of the beauty of letters, I vertical stress relatively low contrast “became insensibly desirous of contributing to the perfection Baskerville is a transitional type of them. I formed to myself ideas of greater accuracy than had yet appeared, and had endeavoured to produce a set of types according to what I conceived to be their true { old style type modern type proportion. oblique stress vertical stress —John Baskerville, preface to Milton, 1758 relatively low contrast high contrast (Anatomy of a Typeface) ” {looks} use of orthogonal lines use of orthogonal + curvy lines FHTt BDp use of curvy lines use of diagonal lines cOQ vwXZ In order to truely appreciate the quialities of Baskerville, one must understand the The Baskerville type is known for the crisp edges, high contrast and generous process of its creation. Being a printer, John Baskerville paid close attention to the proportions. Baskerville is categorized as a transitional typeface in between classical technology, creating his own intense black ink. He boiled fine linseed oil to a certain typefaces and the high contrast modern faces. density, dissolved rosin, and let it subside for months before using it. He also studied and invested in presses, resulting in the development of high standards for presses altogether. {anatomy} crossbar serif ear head serif ascender counter apex A a x g Q b q O spur x-height descender swash {characteristics} {1}g Q {2} A {3} {4}J {5}C {6}E {7}ea {1} tail on lower case g does not close {2} swash-like tail of Q {4} J well below baseline {3} high crossbar and pointed apex of A {5} top and bottom serifs on C {6} long lower arm of E {7} small counter of italic e compared to italic a {comparison} Bembo Baskerville Bembo Baskerville d The head serif of Baskerville is generally more horizontal than that of Bembo. -

Vision Performance Institute

Vision Performance Institute Technical Report Individual character legibility James E. Sheedy, OD, PhD Yu-Chi Tai, PhD John Hayes, PhD The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors that influence the legibility of individual characters. Previous work in our lab [2], including the first study in this sequence, has studied the relative legibility of fonts with different anti- aliasing techniques or other presentation medias, such as paper. These studies have tested the relative legibility of a set of characters configured with the tested conditions. However the relative legibility of individual characters within the character set has not been studied. While many factors seem to affect the legibility of a character (e.g., character typeface, character size, image contrast, character rendering, the type of presentation media, the amount of text presented, viewing distance, etc.), it is not clear what makes a character more legible when presenting in one way than in another. In addition, the importance of those different factors to the legibility of one character may not be held when the same set of factors was presented in another character. Some characters may be more legible in one typeface and others more legible in another typeface. What are the character features that affect legibility? For example, some characters have wider openings (e.g., the opening of “c” in Calibri is wider than the character “c” in Helvetica); some letter g’s have double bowls while some have single (e.g., “g” in Batang vs. “g” in Verdana); some have longer ascenders or descenders (e.g., “b” in Constantia vs. -

Download Futura Font Word

1 / 5 Download Futura Font Word Futuristic Fonts Download Free futuristic fonts at UrbanFonts.com Our site carries ... '80s generator gives your words a neon retro tribute Oct 07, 2016 · Well, if you ... Futuristic Logos Futura Fonts generator tool will let you convert simple and .... Download Futura fonts from UrbanFonts.com for PC and Mac. Futura EF Fonts Free ... Futura Lt Font. How to Install Futura Font in Adobe, Ms Word, Mac or Pc?. 11 Free Chrome Graphics Generators Welcome to MyFonts, the #1 place to download great @font-face webfonts and desktop fonts: classics (Baskerville, Futura, .... Mar 12, 2020 — Want to use beautiful custom fonts in your WordPress theme? ... First thing you need to do is download the font that you like in a web format.. Download Futura PT font (22 styles). Futura PT FuturaPTBold.otf 126 Kb | Futura PT Bold Italic FuturaPTBoldOblique.otf 125 Kb | Futura PT FuturaPTBook.otf ... Download Futura PT Font click here: https://windows10freeapps.com/futura-pt-font-free-download .... Free Font for Designers! High quality design resources for free. And helps introduce first time customers to your products with free fonts downloads and allow .... I'll use Futura PT Heavy which I downloaded from Adobe Typekit, but any font will work: ... This Font used for copy and paste and also for word generator.. Sep 23, 2011 — This is the page of Futura font. You can download it for free and without registration here. This entry was published on Friday, September 23rd .... ... the text it generates may look similar to text generated using the HTML or tags or the CSS attributes font-weight: bold or font-style: italic , it isn't. -

„Bitstream“ Fonts

Key to the „Bitstream“ Fonts The history of typefaces is the history of forgeries. One of the greatest forgers of the 20th century was Matthew Carter. The Bitstream website (http://www.myfonts.com) describes him as follows: Matthew Carter of United Kingdom. Born: 1937 Son of Harry Carter, Royal Designer for Industry, contemporary British type designer and ultimate craftsman, trained as a punchcutter at Enschedé by Paul Rädisch, responsible for Crosfield's typographic program in the early 1960s, Mergenthaler Linotype's house designer 1965-1981. Carter co-founded Bitstream with Mike Parker in 1981. In 1991 he left Bitstream to form Carter & Cone with Cherie Cone. In 1997 he was awarded the TDC Medal, the award from the Type Directors Club presented to those „who have made significant contributions to the life, art, and craft of typography“. Carter’s „significant contribution to the life, art, and craft of typography“ consisted of forging the Linotype typeface collection. Carter can be characterized as a split personality. On the one hand, he has designed several original typefaces. On the other hand, he has forged hundreds of fonts. The following lists reveal that ca. 90% of the „Bitstream“ fonts are forgeries of the fonts contained in the catalog „LinoTypeCollection 1987“ („Mergenthaler Type Library“), i.e. the „Bitstream“ fonts are „nefarious evil knock-off clones“ (Bruno Steinert) of fonts sold by Linotype in the mid-1980s.1 „L“ in the following lists denotes that the font is contained in the „LinoTypeCollection 1987“. In the mid-1980s, the Linotype library comprised hundreds of typefaces with a total of 1700 fonts. -

OMEGA CS Fonts

OMEGA CS Fonts A ACADEMY ENGRAVED ACCT AK REV C American Uncial Inl Accolade Bold American Uncial Shadow Accolade Light AMERICANA BOLD ACCT.AK.REV.C Accolade Light Ita Americana URW T Bol Accolade Med Americana URW T Reg Alcuin Caps URW T Bol Americana URW T Reg Ita Alcuin Caps URW T Lig Americana URW T Xtr Bol Alcuin Caps URW T Reg ANN. GROTESQUE ACCT.A.K.REV.C Alcuin Caps URW T Xtr Bol ANTIQUE OLIVE BOLD ACCT AK REV E Alcuin Discaps URW D Bol ANTIQUE OLIVE MED ACCT AK REV C Alcuin URW T Bol Antique Olive Nord Reg Ita Alcuin URW T Lig ARNOLD BOCKLIN ACCT.A.K.REV.D Alcuin URW T Reg Arnold Boecklin D Alcuin URW T Xtr Bol Arnold Boecklin Initials D Alternate Gothic No1 D Arnold Boecklin No2 Alternate Gothic No2 D Arnold Boecklin Outl Alternate Gothic No3 D ATH.SCRIPT CONN.ACCT.A.K.REV.D American Uncial D AVANT EXTRA BOLD ACCT. AK. REV G American Uncial Initials D AVANT GARDE ACCT. A.K. REV.K B BABYTEETH ACCT.AK REV B Baskerville T Bol Balloon Caps D Xtr Bol Baskerville T Med Balloon D Xtr Bol Baskerville T Med Ita Balloon Drop Shadow D Baskerville T Reg Balloon Outl P Xtr Bol Baskerville T Reg Ita Balloon P Xtr Bol Baskerville URW Bol Balloon URW Bold Baskerville URW BolNar Balloon URW Light Baskerville URW BolNarObl BASKERVILLE ACCT AK REV B Baskerville URW BolObl Baskerville AI Ad Weight Baskerville URW BolWid Baskerville AI Heavy Weight Baskerville URW BolWidObl Baskerville AI Over Weight Baskerville URW BolXtrNar BASKERVILLE BOLD ACCT.A.K.REV.F Baskerville URW BolXtrNarObl Baskerville Handcut Bold Baskerville URW BolXtrWid Baskerville -

Design Principles and Context

MODULE CM 2004 / STAGE 2 / SEMESTER 2 / SESSION 06-07 Module title Design Principles and Context Typography Fonts are classified under the following headings. • Old Face fonts make use of contrasting wide and narrow strokes reminiscent of marks made with a pen. Eg Garamond - http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/itc/garamond Palatino - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=palatino • Script fonts are based upon hand drawn calligraphic shapes Eg Palace Script - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=palace+script • Transitional/Neo Grotesque fonts have highly contrasting wide and narrow strokes and an almost vertical axis. Eg Baskerville - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=baskerville Century - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=century • Modern fonts have contrasting thick and thin strokes. They have a vertical feel and thin serifs. Eg Bodoni - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=bodoni • Slab Serif fonts have heavy and even stroke weights Eg Rockwell - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=rockwell • Humanist fonts originated in the 15th Century and have different stroke thicknesses. Eg Verona - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=verona • Sans Serif fonts have fairly even stroke weights and no serifs (the name “Sans” comes from the French word “Sans” meaning “without” Eg Helvetica - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=helvetica Futura - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=futura Sometimes you may find that a font falls under more than one classification. eg Gill Sans is regarded as a Humanist Sans Serif font Gill Sans - http://www.myfonts.com/search?search%5Btext%5D=gill+sans Style Commonly available type style variations – • Roman • Italic • Condensed • Extended • Thin • Light • Bold • Extrabold Size When discussing the size of font we refer to its Point Size. -

A Brief History of Typefaces the Invention of Printing Movable Type Was Invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Fifteenth-Century Germany

A brief history of typefaces The invention of printing Movable type was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in fifteenth-century Germany. His typography took cues from the dark, dense handwriting of the period, called “blackletter.” The traditional storage of fonts in two cases, one for majuscules and one for minuscules, yielded the terms “uppercase” and “lowercase” still used today. Working in Venice in the late fifteenth century, Nicolas Jenson created letters that combined gothic calligraphic traditions with the new Italian taste for humanist handwriting, which were based on classical models. )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) )ADMIT)HAVEHADALITTLEWORKDONE 2PCFSU4MJNCBDITUZMFE!DOBE+FOTPO BGUFS/JDPMBT+FOTPOTSPNBOUZQFT ANDTHEITALICSOF,UDOVICODEGLI!RRIGHI DSFBUFEJOmGUFFOUIDFOUVSZ*UBMZ )DONTLOOKADAYOVERFIVEHUNDRED DO) The Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius distributed inexpensive, small-format books in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries to a broad, international public. His books used italic types, a cursive form that economized printing by allowing more words to fit on a page. This page combines italic text with roman capitals. Integrated uppercase and lowercase typefaces. The quick brown fox ran over lazy d the lazy dog 2 or 3 times. ITC Garamond, 1976 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Adobe Garamond, 1986 The quick brown fox ran over the lazy d lazy dog 2 or 3 (2 or 3) times. Garamond Premier Regular, 2005 Garamond typefaces, based on the Renaissance designs of Claude Garamond, sixteenth century Enlightenment and abstraction The painter and designer Geofroy Tory believed that the proportions of the alphabet should reflect the ideal human form. -

Bitstream Font Name Aliases Fontotéka 3.0 Compiled by Petr Somol, Based on Jon A

Bitstream Font Name Aliases fontotéka 3.0 Compiled by Petr Somol, based on Jon A. Pastor‘s list from http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/jonpastor.txt. E-mail: [email protected] The list should not be considered complete, nor accurate. It is more a work in progress than anything else. Bitstream Name Common Name Designer(s) Date(s) Orig. Remarks/Attributions Vend. (all) (M.Macrone/J.Pastor,P.S.) (M.M,P.S.) (J.P., P.S.) Aachen Aachen Colin Brignall, Alan Meeks 1969-1977 17 Ad Lib Ad Lib Freeman Craw 1961 6 Aldine 401 Bembo Stanley Morison after Francesco 1929 after 1,4 Griffo / Giovanni Tagliente 1495 / 1520 Aldine 721 Plantin Frank Hinman Pierpont after ~1930 after 1,4 Robert Granjon‘s type used by 16th ~1550 / 16h century printer Christophe Plantin cent. Alternate Gothic No. 2 Alternate Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1903 6 Amazone Amazone Leonard H. D. Smit 1958 12 Amelia Amelia Stanley Davis 1967 18, 2 American Text American Text Morris Fuller Benton 1932 6 Americana Americana Richard Isbell, Whedon Davis 1965 6 Aurora Aurora ? 1928 (c.) 11 Baker Signet Baker Signet Arthur Baker 1965 18 Balloon Balloon Max R. Kaufmann 1939 6 Bank Gothic Bank Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1930-33 6 Baskerville Baskerville George W. Jones after John 1929 after 2 Baskerville ~1754-1775 Baskerville No.2 Baskerville No.2 ? ? 19 Bauer Bodoni Bauer Bodoni Heinrich Jost, Louis Höll after 1926 after 8 Giambattista Bodoni ~1800 Bell Gothic Bell Gothic Chauncey H. Griffith 1938 2 Belwe Belwe Georg Belwe before 1950 20 Bernhard Bold Con- Bernhard Bold Con- Lucian Bernhard -

Typography Evolved from Handwriting, Which Is Created By

PARTS OF THE LETTER Typography evolved from handwriting, which is created by making a series of marks by hand; therefore, the fundamen- tal element constructing a letterform is the linear stroke (stem). Each letter of our alphabet developed as a simple mark whose visual characteristics clearly sepa- rated it from all others. PARTS OF THE LETTER By learning the vocabulary designers and typographers can develop a greater understanding and sensitivity to the visual harmony and complexity of the alphabet. PARTS OF THE LETTER As with any craft that has evolved over 500 years, typography employs a number of technical terms. We will be learning these terms throughout the semester. The following describes specific parts of letterforms. Knowing the letterform component parts will make it much easier to identify specific typeface in the future. serif: the short strokes that finish off the major strokes of the letterform. bracket: a curving joint between the serif and the stroke bracket A baskerville bodoni rockwell Atransitional Amodern slab serif extreme thick and thins nearly mono-weight stroke width A baskerville bodoni rockwell Atransitional Amodern slab serif extreme thick and thins nearly mono-weight baseline: the imaginary line defining the visual base of the letterform. all letterforms sit on the baseline. baseline xAapdeCGgQk cap height: the height of the upper case in a font, taken from the base- line to the top of the character. cap height baseline xAapdeCGgQk x-height: the height lowercase x. if you compare typefaces of the same point size they may not have the same x-height. all of the lowercase x’s are the same point size. -

Parent Ad Style Guide

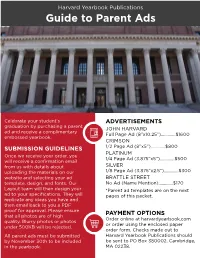

Harvard Yearbook Publications Guide to Parent Ads Celebrate your student’s ADVERTISEMENTS graduation by purchasing a parent JOHN HARVARD ad and receive a complimentary Full Page Ad (8”x10.25”).............$1600 embossed yearbook. CRIMSON SUBMISSION GUIDELINES 1/2 Page Ad (8”x5”).............$800 PLATINUM Once we receive your order, you 1/4 Page Ad (3.875”x5”).............$500 will receive a confirmation email from us with details about SILVER uploading the materials on our 1/8 Page Ad (3.875”x2.5”).............$300 website and selecting your ad BRATTLE STREET template, design, and fonts. Our No Ad (Name Mention).............$170 Layout team will then design your *Parent ad templates are on the next ad to your specifications. They will pages of this packet. replicate any ideas you have and then email back to you a PDF proof for approval. Please ensure that all photos are of high PAYMENT OPTIONS Order online at harvardyearbook.com quality. Blurry photos or photos or order using the enclosed paper under 500KB will be rejected. order form. Checks made out to All parent ads must be submitted Harvard Yearbook Publications should by November 30th to be included be sent to PO Box 380002, Cambridge, in the yearbook. MA 02238. ADVERTISEMENT SIZE: SILVER (1/8 PAGE) - 3.875 x 2.5 in. Layout: Silver #1 John Harvard Font: Times (Bold & Regular) Congratulations on all of your accomplishments! We are so very proud of you. Love, Mom, Dad, and Drew Layout: Silver #2 John Harvard Font: Arial (Bold & Regular) Congratulations on all of your accomplishments! We are so very proud of you.