Palawan, the Calamianes Islands and Esperanza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2017 Palawan Council for Sustainable Development

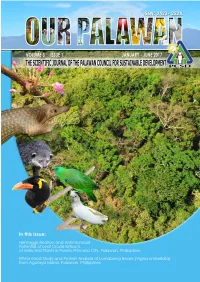

© 2017 Palawan Council for Sustainable Development OUR PALAWAN The Scientific Journal of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Volume 3 Issue 1, January - June 2017 Published by The Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) PCSD Building, Sports Complex Road, Brgy. Sta. Monica Heights, Puerto Princesa City P.O. Box 45 PPC 5300 Philippines PCSD Publications © Copyright 2017 ISSN: 2423-222X Online: www.pkp.pcsd.gov.ph www.pcsd.gov.ph Cover Photo The endemic species of Palawan and Philippines (from top to bottom) : Medinilla sp., Palawan Pangolin Manus culionensis spp., Palawan Bearcat Arctictis binturong whitei, Palawan Hill Mynah Gracula religiosa palawanensis, Blue-naped parrot Tanygnathus lucionensis, Philippine Cockatoo Cacatua haematuropydgia. (Photo courtesy: PCSDS) © 2017 Palawan Council for Sustainable Development EDITORS’ NOTE Our Palawan is an Open Access journal. It is made freely available for researchers, students, and readers from private and government sectors that are interested in the sustainable management, protection and conservation of the natural resources of the Province of Palawan. It is accessible online through the websites of Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (pcsd.gov.ph) and Palawan Knowledge Platform for Biodiversity and Sustainable Development (pkp.pcsd.gov.ph). Hard copies are also available in the PCSD Library and are distributed to the partner government agencies and academic institutions. The authors and readers can read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to -

A5 8Pp Format

Palawan ‘CAN ’ Palawan is 1,780 islands of pristine white beaches, dramatic rock A nature lover ’s paradise and an formations, secret coves and underground mysteries. An untamed CULTURE . The island province of Palawan land, a nature lover’s paradise and an adventurer’s dream: Palawan adventurer ’s dream has much to offer to those who want to get to certainly lives up to its image as the last frontier. LAOAG the heart and soul of the Philippines. The more Getting there adventurous traveller can visit one of Palawan’s The island province has been declared a nature sanctuary of the world Palawan Banaue Major Airport Gateways: indigenous people, the Batak, whose settlements and for good reason. It is wrapped in a mantel of rainforests, outstanding Luzon dive sites, majestic mountains, primeval caves and shimmering beaches. Puerto Princesa, El Nido, Sandoval, Busuanga and PHILIPPINE SEA are on the slope of Cleopatra’s Needle. The Tabon Cuyo. Distance from Manila to Puerto Princesa is and Palawan Museums with their displays of It bursts with exotic flora and fauna and is surrounded by a coral shelf 306 nautical miles MANILAMMAMANMANIMANIL prehistoric artifacts from the Tabon caves and that abounds with varied and colourful marine life. Air Transport: items from the Spanish era bring the areas’ local Mindoro The long narrow strip of the main island, located southwest of Manila, Various domestic carriers fly to Palawan's major history to life and are well worth exploring. gateways from Manila (20+ flights daily), Cebu Busuanga Boracay Samar is around 425 kilometres long and 40 kilometres at its widest. -

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

Diversity, Habitat Distribution, and Indigenous Hunting of Marine Turtles

JAPB111_proof ■ 23 January 2016 ■ 1/5 Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity xxx (2016) 1e5 55 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect 56 57 Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 58 59 60 journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/japb 61 62 63 Original article 64 65 1 Diversity, habitat distribution, and indigenous hunting of marine 66 2 67 3 turtles in the Calamian Islands, Palawan, Republic of the Philippines 68 4 69 a,b,* b b 5 Q16 Christopher N.S. Poonian , Reynante V. Ramilo , Danica D. Lopez 70 6 a 71 7 Community Centred Conservation (C3), London, UK b C3 Philippines and Micronesia Programme, Busuanga, Philippines 72 8 73 9 74 10 article info abstract 75 11 76 12 Article history: All of the world’s seven species of marine turtle are threatened by a multitude of anthropogenic pres- 77 13 Received 26 May 2015 sures across all stages of their life history. The Calamian Islands, Palawan, Philippines provide important 78 14 Received in revised form foraging and nesting grounds for four species: green turtles (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill turtles (Eret- 79 22 December 2015 15 mochelys imbricata), loggerheads (Caretta caretta), and leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea). This work 80 Accepted 30 December 2015 16 aimed to assess the relative importance of turtle nesting beaches and local threats using a combination of Available online xxx 81 17 social science and ecological research approaches. Endangered green turtles and critically endangered 82 hawksbills were found to nest in the Calamianes. The most important nesting sites were located on the 18 Keywords: 83 islands off the west of Busuanga and Culion, particularly Pamalican and Galoc and along the north coast 19 Busuanga 84 20 Q1 Coron of Coron, particularly Linamodio Island. -

24Th Annual Philippine Biodiversity Symposium

24th Annual Philippine Biodiversity Symposium University of Eastern Philippines Catarman, Northern Samar 14-17 April 2015 “Island Biodiversity Conservation: Successes, Challenges and Future Direction” th The 24 Philippine Biodiversity Symposium organized by the Biodiversity Conservation Society of the Philippines (BCSP), hosted by the University of Eastern Philippines in Catarman, Northern Samar 14-17 April 2015 iii iv In Memoriam: William Langley Richardson Oliver 1947-2014 About the Cover A Tribute to William Oliver he design is simply 29 drawings that represent the endemic flora and fauna of the Philip- illiam Oliver had spent the last 30 years working tirelessly pines, all colorful and adorable, but the characters also all compressed and crowded in a championing threatened species and habitats in the small area or island much like the threat of the shrinking habitats of the endemics in the Philippines and around the world. William launched his islands of the Philippines. This design also attempts to provide awareness and appreciation W wildlife career in 1974 at the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust. In Tof the diverse fauna and flora found only in the Philippines, which in turn drive people to under- 1977, he undertook a pygmy hog field survey in Assam, India and from stand the importance of conserving these creatures. There are actually 30 creatures when viewing then onwards became a passionate conservationist and defender the design, the 30th being the viewer to show his involvement and responsibility in conservation. of the plight of wild pigs and other often overlooked animals in the Philippines, Asia and across the globe. He helped establish the original International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Pigs and Peccaries Specialist Group in 1980 at the invitation of British conservationist, the late Sir Peter Scott. -

Nuisance Behaviors of Macaques in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park, Palawan, Philippines

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles online OPEN ACCESS every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Nuisance behaviors of macaques in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park, Palawan, Philippines Lief Erikson Gamalo, Joselito Baril, Judeline Dimalibot, Augusto Asis, Brian Anas, Nevong Puna & Vachel Gay Paller 26 February 2019 | Vol. 11 | No. 3 | Pages: 13287–13294 DOI: 10.11609/jot.4702.11.3.13287-13294 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, the host, and the part- Publisher & Host ners are not responsible for the accuracy of the politcal boundaries shown in the maps by the authors. -

Discovery O F Triassic Conodonts from Uson Islands O F the Calamian

No. 2] Proc. Japan Acad., 56, Ser. B (1980) 69 14. Discovery of Triassic Conodonts from Malajon and Uson Islands of the Calamian Island Group, Palawan Province, the Philippines, and Its Geological Significance By wataru HASHIM0T0,*) Shigeru TAKIZAWA,**) Guillermo R. BALCE, * * * ) Ernesto A. ESPIRITU, * * * and Crisanto A. BAURA* * * > (Communicated by Teiichi KoBAYASxi, M. J. A., Feb. 12, 1980) This short article deals with the discovery of Epigondolella ab- neptis (Huckriede) , a Lower Norian index conodont of Japan, in the limestone at the southeastern coast of Malajon Island, the Calamian Island Group, and its geological significance. The general geology of the Calamian Island Group had not been surveyed since Smith (1924) reported the manganese-bearing chert formation from Busuanga Island and limestone from Coron Island, until 1978, when H. Fontaine reported the geological and palaeon- tological results of his reconnaissance works conducted in this island group (Fontaine, 1978, 1979; Fontaine et al., 1979). The Calamian Island Group is geographically situated between Mindoro and Palawan Islands, where the Mindoro and the Palawan Metamorphics are exposed respectively. Concerning the origin of these schists in the Recent Palawan Arc trending from Palawan to Mindoro, Gervasio (1971) and Hashimoto and Sato (1973) are of different opinions. Gervasio (1971) referred to the schist in the Palawan Arc as the basement of the Philippines and the non-metamorphosed Palaeozoic sediments including limestone in northern Palawan as well as that in the Calamian Island Group and the Permian limestone on Carabao Island as Palaeozoic formation deposited in a miogeosyncline, occur- ring in an east-west direction upon the basement schist terrain. -

The IUCN Wild Pig Challenge 2015

The IUCN Wild Pig Challenge 2015 M ATTHEW L INKIE,JASLINE N G ,ZHI Q I L IM,MUHAMMAD I. LUBIS M ARK R ADEMAKER and E RIK M EIJAARD Abstract Asian mammal species are facing unprecedented Sumatra it is often referred to as lumba lumba pressures from hunting and habitat conversion. Efforts to (Indonesian for dolphin) because local people believe that mitigate these threats often focus on charismatic large-bodied when sounders of up to foraging pigs disappear from species, while many other species or even guilds receive less a forest patch they turn into dolphins and swim to the sea. attention, particularly Asian wild pigs. To address this we de- Also, because of their importance to many communities, veloped a rapid questionnaire survey and administered it to wild pigs are considered to be cultural keystone species. relevant experts to identify the presence, population trends The IUCN/SSC Wild Pig Specialist Group seeks to raise and conservation needs of Asia’s threatened wild pig spe- the profile of wild pigs, draw attention to their plight and cies. The results highlighted geographical differences within support conservation interventions. Of the extant pig spe- species (e.g. the near collapse of bearded pig populations in cies in the Suidae family, occur in Asia and of these are Peninsular Malaysia yet their widespread presence on threatened with extinction (categorized as Vulnerable, Borneo), and knowledge gaps for many endemic species of Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red the Philippines, notably the Critically Endangered Visayan List; IUCN, ), mainly as a result of hunting and loss of warty pig Sus cebifrons. -

SPR(2006).Calamianes

Summary Field Report: Saving Philippine Reefs Coral Reef Surveys for Conservation in Calamianes Islands, Palawan, Philippines April, 2006 A joint project of: Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, In. and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project With the participation and support of the Expedition volunteers THE DAVID AND LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION Summary Field Report “Saving Philippines Reefs” Coral Reef Monitoring Expedition to the Calamianes Islands, Palawan, Philippines April 8-16, 2006 A Joint Project of: The Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. (formerly Sulu Fund for Marine Conservation, Inc.) and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project With the participation and support of the Expedition Volunteers Principal investigators and primary researchers: Alan T. White, Ph.D. Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project Tetra Tech EM Inc., Cebu, Philippines Aileen Maypa, M.Sc. Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. Cebu, Philippines Sheryll C. Tesch Anna T. Meneses Brian Stockwell, M.Sc. Evangeline E. White Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. Rafael Martinez Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project Summary Field Report: “Saving Philippine Reefs” Coral Reef Monitoring Expedition to Calamianes Islands, Palawan, Philippines, April 8-16, 2006. Produced by the Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project Cebu City, Philippines Citation: White, A.T., A. Maypa, S. Tesch, A. Meneses, B. Stockwell, E. White and R. Martinez. 2006. Summary Field Report: Coral Reef Monitoring Expedition to Calamianes Islands, Palawan, Philippines, April 8-16, 2006. The Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, Cebu City, 92p. -

Culion Municipality

BASELINE REPORT ON COASTAL RESOURCES for Culion Municipality September 2006 Prepared for: PALAWAN COUNCIL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Palawan Center for Sustainable Development Sta. Monica Heights, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines 5300 Email: [email protected] Tel.: (63-48) 434-4235, Fax: 434-4234 Funded through a loan from : JAPAN BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION Prepared by: PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL in association with ALMEC Corporation CERTEZA Information Systems, Inc. DARUMA Technologies Inc. Geo-Surveys & Mapping, Inc. Photo Credits: Photos by PCSDS and SEMP-NP ECAN Zoning Component Project Management Office This report can be reproduced as long as the convenors are properly acknowledged as the source of information Reproduction of this publication for sale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the written consent of the publisher. Printed by: Futuristic Printing Press, Puerto Princesa City, Philippines Suggested Citation: PCSDS. 2006. Baseline Report on Coastal Resources for Culion, Municipality. Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables v List of Figures vii List of Plates x List of Appendices xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xii CHAPTER I: CORAL REEFS 1 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Materials and Methods 6 3.0 Survey Results 7 4.0 Discussions 10 5.0 Summary 12 6.0 Recommendations 12 CHAPTER II: REEF FISHES 13 7.0 Introduction 13 8.0 Materials and Methods 13 9.0 Results 14 10.0 Discussions 21 11.0 Conclusions and Recommendations 22 CHAPTER III: SEAGRASSES -

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE in the PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-Largest Archipelago in the World Comprising 7,641 Islands

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN THE PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-largest archipelago in the world comprising 7,641 islands Current population is 100 million, but projected to reach 125 million by 2030; most people, particularly the poor, depend on biodiversity 114 species of amphibians 240 Protected Areas 228 Key Biodiversity Areas 342 species of reptiles, 68% are endemic One of only 17 mega-diverse countries for harboring wildlife species found 4th most important nowhere else in the world country in bird endemism with 695 species More than 52,177 (195 endemic and described species, half 126 restricted range) of which are endemic 5th in the world in terms of total plant species, half of which are endemic Home to 5 of 7 known marine turtle species in the world green, hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE The value of Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is estimated at $10 billion–$23 billion per year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and arms. The Philippines is a consumer, source, and transit point for IWT, threatening endemic species populations, economic development, and biodiversity. The country has been a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity since 1992. The value of IWT in the Philippines is estimated at ₱50 billion a year (roughly equivalent to $1billion), which includes the market value of wildlife and its resources, their ecological role and value, damage to habitats incurred during poaching, and loss in potential -

Free and Prior Informed Consent

Is the Concept of “Free and Prior Informed Consent” Effective as a Legal and Governance Tool to Ensure Equity among Indigenous Peoples? (A Case Study on the Experience of the Tagbanua on Free Prior Informed 1 Consent, Coron Island, Palawan, Philippines) Grizelda Mayo-Anda, Loreto L. Cagatulla, Antonio G. M. La Viňa EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Free and Prior Informed Consent is a process established under Philippine law which seeks to guarantee the participation of indigenous communities in decision making on matters affecting their common interests. This paper looks into the experience of the Tagbanua indigenous community of Coron Island, Palawan, Philippines on the application of the concept of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). The study area focused on the two Tagbanua communities in Coron Island - Barangays Banuang Daan and Cabugao. Coron Island is home to the seafaring Tagbanua tribes and has been identified as one of the country’s important areas for biodiversity.. The Tagbanua community has managed to secure their tenure on the island and its surrounding waters through the issuance and recognition by the government of an ancestral domain title, one of the first examples of its kind in the Philippines. The study concludes that the exercise of Free Prior and Informed Consent by the Tagbanua community is an important and fundamental tool to ensure that the indigenous peoples will benefit from the resources within their ancestral territory. Among others, it has given them a new tool to protect their environment and to obtain an equitable share of the economic benefits of their natural resources. The study also shows that the exercise of Free Prior and Informed Consent by the Tagbanua communities of Barangays Banuang Daan and Cabugao was recognized by government and non-government stakeholders, although in varying degrees.