Cash Alliance's Food Security and Livelihoods Project in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reserve 2016 Direct Beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 0 500 1

Requesting Organization : CARE Somalia Allocation Type : Reserve 2016 Primary Cluster Sub Cluster Percentage Nutrition 100.00 100 Project Title : Emergency Nutritional support for the Acutely malnourished drought affected population in Qardho and Bosaso Allocation Type Category : OPS Details Project Code : Fund Project Code : SOM-16/2470/R/Nut/INGO/2487 Cluster : Project Budget in US$ : 215,894.76 Planned project duration : 8 months Priority: Planned Start Date : 01/05/2016 Planned End Date : 31/12/2016 Actual Start Date: 01/05/2016 Actual End Date: 31/12/2016 Project Summary : This Project is designed to provide emergency nutrition assistance that matches immediate needs of drought affected women and children (boys and girls) < the age of 5 years in Bari region (Qardho and Bosaso) that are currently experiencing severe drought conditions. The project will prioritize the management of severe acute malnutrition and Infant and Young child Feeding (IYCF) and seeks to provide emergency nutrition assistance to 2500 boys and girls < the age of 5 years and 500 pregnant and lactating women in the drought affected communities in Bosaso and Qardho. Direct beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 0 500 1,250 1,250 3,000 Other Beneficiaries : Beneficiary name Men Women Boys Girls Total Children under 5 0 0 1,250 1,250 2,500 Pregnant and Lactating Women 0 500 0 0 500 Indirect Beneficiaries : Catchment Population: 189,000 Link with allocation strategy : The project is designed to provide emergency nutrition support to women and children that are currently affected by the severe drought conditions. The proposed nutrition interventions will benefit a total of 2500 children < the age of 5 years and 500 Pregnant and lactating women who are acutely malnourished. -

COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment

COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment PUNTLAND The information contained in this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission but with acknowledgement of this publication as a source. Suggested citation: Puntland Statistics Department, Puntland State of Somalia. COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment.. Additional information about the survey can be obtained from: Puntland Statistics Department, Ministry of Planning, Economic Development and International Cooperation, Puntland State of Somalia. Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.mopicplgov.net https://www.moh.pl.so http://www.pl.statistics.so Telephone no.: +252 906796747 or 00-252-5-843114 Social media: https://www.facebook.com/mopicpl https://www.facebook.com/ministryOfHealthPuntlamd/ https://twitter.com/PSD_MoPIC This report was produced by the Puntland State of Somalia, with support from the United Nations Population Fund, Somalia and key donors. COVID-19 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment PUNTLAND With technical support from: With financial contribution from: Puntland COVID-19 Report Foreword Today, Somalia and the world at large face severe Covid-19 pandemic crisis, coronavirus has no boundaries. It has severely affected the lives of people from different backgrounds. Across Somalia, disruptions of supply chains and closure of businesses has left workers without income, many of whom are vulnerable members in the society. The COVID-19 pandemic characterized by airports and border closures as well as lockdowns, is an economic and labour market shock, impacting not only supply but also demand. In Puntland, the implementation of lockdown measures has placed a major distress on the food value-chains, in particularly the international trade remittances from abroad and Small and Micro Enterprise Sector (SMEs) which are considered to be the main source of livelihoods for a greater part of the Somali population. -

Report of the Tsunami Inter Agency Assessment Mission, Hafun to Gara

TSUNAMI INTER AGENCY ASSESSMENT MISSION Hafun to Gara’ad Northeast Somali Coastline th th Mission: 28 January to 8 February 2005 2 Table of Content Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Description of the Tsunami.............................................................................................................. 12 2.2 Description of the Northeast coastline............................................................................................. 13 2.3 Seasonal calendar........................................................................................................................... 14 2.4 Governance structures .................................................................................................................... 15 2.5 Market prices ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.6 UN Agencies and NGOs (local and international) on ground.......................................................... 16 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 17 4. Food, Livelihood & Nutrition Security Sector......................................................................................... -

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law Pillars of Peace Somali Programme Garowe, November 2015 Acknowledgment This Report was prepared by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) and the Interpeace Regional Office for Eastern and Central Africa. Lead Researchers Research Coordinator: Ali Farah Ali Security and Rule of Law Pillar: Ahmed Osman Adan Democratization Pillar: Mohamoud Ali Said, Hassan Aden Mo- hamed Decentralization Pillar: Amina Mohamed Abdulkadir Audio and Video Unit: Muctar Mohamed Hersi Research Advisor Abdirahman Osman Raghe Editorial Support Peter W. Mackenzie, Peter Nordstrom, Jessamy Garver- Affeldt, Jesse Kariuki and Claire Elder Design and Layout David Müller Printer Kul Graphics Ltd Front cover photo: Swearing-in of Galkayo Local Council. Back cover photo: Mother of slain victim reaffirms her com- mittment to peace and rejection of revenge killings at MAVU film forum in Herojalle. ISBN: 978-9966-1665-7-9 Copyright: Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) Published: November 2015 This report was produced by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) with the support of Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contribut- ing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use -

Enhanced Enrolment of Pastoralists in the Implementation and Evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia

Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia Prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute UNICEF ESARO JUNE 2013 Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia © United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Nairobi, 2013 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) PO Box 44145-00100 GPO Nairobi June 2013 The report was prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF. The text has not been edited to official publication standards and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this publication do not imply an opinion on legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. For further information, please contact: Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel: [email protected] Eugenie Reidy, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Dorothee Klaus, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Cover photograph © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2301/Kate Holt 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Wash Cluster Meeting Minutes

WASH CLUSTER MEETING MINUTES Meeting WASH Cluster Meeting Date 06-01-2020 Time 9;00am Venue CARE Bosaso Office Participants S/N Name Agency Email Telephone 1 Dauud Said Ahmed AADSOM [email protected] 907738443 2 Mohamed Bardacad SCI [email protected] 907772900 3 Naimo Ali Nur MOH [email protected] 907744895 4 Abdirashid Abdullahi Osman PWDA [email protected] 907735581 5 Abshir Bashir Isse DRC [email protected] 907780907 6 Said Arshe Ahmed CARE [email protected] 907799710 7 Ahmed said Salaad NRC [email protected] 907795829 8 Said Mohamed Warsame SEDO [email protected] 907798446 9 Mohamed Abdiqadir Jama CARE [email protected] 906798053 10 Mohamed Ali Harbi SHILCON [email protected] 907638045 Agenda Items 1. Introduction and Open remarks among the members. 2. Review of the last meeting action points 3. PWDA updates for the floods affected water sources in Bari and Sanaag 4. Updates of the ongoing Wash interventions as well the projects in the pipeline in Bari and Sanaag. 5. Setting the yearly Wash cluster meeting schedule (Wash Meeting Calendar) 6. Sharing the hygiene and sanitation plans to Bosaso Local Authority 7. AOB Introduction and Opening remarks The WASH cluster chair opened and welcomed the participants to the WASH Cluster meeting in CARE Bosasso office and then an introduction between the participants was flowed and then the meeting agenda was outlined. Review of the last meeting action points The action points from the last meeting was reviewed. 1. PWDA will share the updates and Data of list of water sources in Bari and sanaag Regions to the Cluster. -

Somalia (Puntland & Somaliland)

United Nations Development Programme GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION SOMALIA (PUNTLAND & SOMALILAND) CASE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY FACTS .................................................................................................................................. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................................................. 4 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 6 CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................... 7 Socio-economic and political context .............................................................................................. 7 Gender equality context....................................................................................................................... 8 Public administration context .......................................................................................................... 12 WOMEN’S PARTICIPATION IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION .................................................16 POLICY AND IMPLEMENTATION REVIEW ............................................................................18 Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development Programme ................................................ -

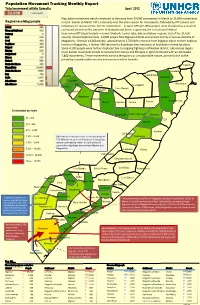

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report Total movement within Somalia April 2012 33,000 nationwide Population movement trends continued to decrease from 39,000 movements in March to 33,000 movements Region receiving people in April. Similar to March 2012, insecurity was the main reason for movements, followed by IDP returns and Region People Awdal 400 temporary or seasonal cross border movements. In April, 65% (21,000 people) were displaced as a result of Woqooyi Galbeed 500 continued armed conflict between Al Shabaab and forces supporting the Transitional Federal Sanaag 0 Government(TFG) particularly in Lower Shabelle, Lower Juba, Bay and Bakool regions. Out of the 21,000 Bari 200 security related displacements, 14,000 people fled Afgooye district and arrived mainly in various districts of Sool 400 Mogadishu. Of these 14,000 people, approximately 3,700 IDPs returned from Afgooye closer to their habitual Togdheer 100 homes in Mogadishu, a further 590 returned to Baydhaba after cessation of hostilities in these locations. Nugaal 400 Some 4,100 people were further displaced due to ongoing fighting in Afmadow district, Juba Hoose region. Mudug 500 Cross border movement trends to Somalia from Kenya and Ethiopia in April continued with an estimated Galgaduud 0 2,800 movements. These movements are of a temporary or unsustainable nature, primarily due to the Hiraan 200 Bakool 400 prevailing unpredictable security environment within Somalia. Shabelle Dhexe 300 Caluula Mogadishu 20,000 Shabelle Hoose 1,000 Qandala Bay 700 Zeylac Laasqoray Gedo 3,200 Bossaso Juba Dhexe 100 Lughaye Iskushuban Juba Hoose 5,300 Baki Ceerigaabo Borama Berbera Ceel Afweyn Sheikh Gebiley Hargeysa Qardho Odweyne Bandarbeyla Burco Caynabo Xudun Taleex Estimated arrivals Buuhoodle Laas Caanood Garoowe 30 - 250 Eyl Burtinle 251 - 500 501 - 1,000 Jariiban Goldogob 1,001 - 2,500 IDPs who were displaced due to tensions between Gaalkacyo TFG-Allied forces and the Al Shabaab in Baydhaba 2,501 - 5,000 district continued to return. -

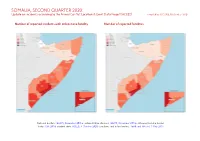

SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Ethiopia/Somalia border status: CIA, 2014; incident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 327 152 465 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 146 100 144 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Explosions / Remote 133 59 187 violence Methodology 3 Protests 28 1 1 Conflict incidents per province 4 Strategic developments 18 2 2 Riots 6 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 658 314 799 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

THE PUNTLAND STATE of SOMALIA 2 May 2010

THE PUNTLAND STATE OF SOMALIA A TENTATIVE SOCIAL ANALYSIS May 2010 Any undertaking like this one is fraught with at least two types of difficulties. The author may simply get some things wrong; misinterpret or misrepresent complex situations. Secondly, the author may fail in providing a sense of the generality of events he describes, thus failing to position single events within the tendencies, they belong to. Roland Marchal Senior Research Fellow at the CNRS/ Sciences Po Paris 1 CONTENT Map 1: Somalia p. 03 Map 02: the Puntland State p. 04 Map 03: the political situation in Somalia p. 04 Map 04: Clan division p. 05 Terms of reference p. 07 Executive summary p. 10 Recommendations p. 13 Societal/Clan dynamics: 1. A short clan history p. 14 2. Puntland as a State building trajectory p. 15 3. The ambivalence of the business class p. 18 Islamism in Puntland 1. A rich Islamic tradition p. 21 2. The civil war p. 22 3. After 9/11 p. 23 Relations with Somaliland and Central Somalia 1. The straddling strategy between Somaliland and Puntland p. 26 2. The Maakhir / Puntland controversy p. 27 3. The Galmudug neighbourhood p. 28 4. The Mogadishu anchored TFG and the case for federalism p. 29 Security issues 1. Piracy p. 31 2. Bombings and targeted killings p. 33 3. Who is responsible? p. 34 4. Remarks about the Puntland Security apparatus p. 35 Annexes Annex 1 p. 37 Annex 2 p. 38 Nota Bene: as far as possible, the Somali spelling has been respected except for “x” replaced here by a simple “h”. -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Somalia: Floods in Qardho

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Somalia: Floods in Qardho DREF Operation MDRSO009 Glide n°: FF-2020-000055-SOM Date of issue: 14 May 2020 Expected timeframe: 3 months Operation start date: 13 May 2020 Expected end date: 31 August 2020 Disaster / Crisis Category: Yellow DREF allocated: CHF 328,070 Total number of people 48,000 people (8,000 HHs) Number of people to be 9,000 people (1,500HHs) affected: assisted: Provinces affected: Puntland, Somalia Provinces/Regions Qardho targeted: Host National Society presence: Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS) has a Liaison Office in Nairobi where the National Society President sits with a small team. In addition, SRCS has two Coordination Offices in-country, one in Mogadishu and one in Hargeisa, which are managed by two Executive Directors. Mogadishu Coordination office manages 13 branches including those in Puntland (Garowe, Bosaso and North Galkaio). SRCS has a Branch in Bossaso and a Sub-Branch in Qardho. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Turkish Red Crescent Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management Agency (HADMA), UN (OCHA, WFP, HCR, FPA), INGOs (SC, CARE, WVI, Islamic Relief, NRC), NGOs (KAALO, PDO, PSA) and still evolving. <Please click here for the financial report and here for the contacts> A. Situation analysis Description of the Disaster. According to ECHO Daily Flash of 29 April, heavy rains are affecting most of Somalia States and territories since 20 April 2020, including South West, Jubaland, Banadir, Puntland, and Somaliland, causing rivers to overflow and triggering floods that have resulted in casualties and damage. -

RESPONSE to YEMEN SITUATION 1-31 May 2017

SOMALIA RESPONSE TO YEMEN SITUATION 1-31 May 2017 HIGHLIGHTS 504 new arrivals from Yemen 3,661 individuals provided with health care assistance 193 core relief items distributed to 188 households (350 individuals) 5,074 individuals provided with cash grants 955 beneficiaries enrolled in community-based projects NEW ARRIVALS Nationality 1-31 May 2017 2017 Cumulatively Somalis 417 2,071 31,546 Yemenis 78 422 5,394 Third country nationals 9 14 327 Total 504 2,507 37,267 UNHCR providing leaflets on services available in Somalia for new arrivals. © UNHCR/Berbera/May 2017 www.unhcr.org 1 Response to Yemen Situation - Somalia - May 2017 UPDATE ON ACHIEVEMENTS The King Salman Center for Humanitarian Aid and Relief (KS-Relief) conducted a field visit to Somalia to observe progress on projects funded by them. The delegation visited sites in Mogadishu where they met with local authorities and partners, and visited several programme sites launched under the KS-Relief contribution. PROTECTION New arrivals In May, 504 new arrivals (417 Somalis, 78 Yemenis, eight Ethiopians and one Djiboutian) arrived from Yemen to Somalia by boat. In 2017, 2,507 new arrivals, including 2,071 Somalis, 422 Yemenis and 14 nationals from various other countries arrived from Yemen to Somalia. Since the beginning of the conflict in Yemen in March 2015, 37,267 new arrivals were recorded in Somalia; 31,546 Somalis, 5,394 Yemenis and 327 third country nationals. Arrivals from Yemen by month in 2017 Cumulative arrivals by nationality Registration: In May, a total of 256 persons of concern; 161 Somalis, 93 Yemenis, one Djiboutian and one Ethiopian, were registered.