Program Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai Quartet 2020-21 Biography

SHANGHAI QUARTET 2020-21 BIOGRAPHY Over the past thirty-seven years the Shanghai Quartet has become one of the world’s foremost chamber ensembles. The Shanghai’s elegant style, impressive technique, and emotional breadth allows the group to move seamlessly between masterpieces of Western music, traditional Chinese folk music, and cutting-edge contemporary works. Formed at the Shanghai Conservatory in 1983, soon after the end of China’s harrowing Cultural Revolution, the group came to the United States to complete its studies; since then the members have been based in the U.S. while maintaining a robust touring schedule at leading chamber-music series throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. Recent performance highlights include performances at Carnegie Hall, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Freer Gallery (Washington, D.C.), and the Festival Pablo Casals in France, and Beethoven cycles for the Brevard Music Center, the Beethoven Festival in Poland, and throughout China. The Quartet also frequently performs at Wigmore Hall, the Budapest Spring Festival, Suntory Hall, and has collaborations with the NCPA and Shanghai Symphony Orchestras. Upcoming highlights include the premiere of a new work by Marcos Balter for the Quartet and countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo for the Phillips Collection, return performances for Maverick Concerts and the Taos School of Music, and engagements in Los Angeles, Syracuse, Albuquerque, and Salt Lake City. Among innumberable collaborations with eminent artists, they have performed with the Tokyo, Juilliard, and Guarneri Quartets; cellists Yo-Yo Ma and Lynn Harrell; pianists Menahem Pressler, Peter Serkin, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, and Yuja Wang; pipa virtuoso Wu Man; and the vocal ensemble Chanticleer. -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

I .Concert Theatre Tonight!

FIL™ n r a "WS ■ J O 3 : BOYS îîS*!9â k IWâ S 7A FEATURE 3 A | REVIEW Actors Ricky From the Ricardo's London Logical Stage Heir The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus/For the Week of Oct.25-Nov.2 1989 Syllabus OF NOTE THIS WEEK MUSIC Top 5 This Week at Rockhouse Records: 1. Camper Van Beethoven Key Lime Pie 2. Erasure Wild 3. Jesus & Mary Chain Automatic 4. Kate Bush The Sensual World 5. Aerosmith Pump at The Wherehouse: 1. Rolling Stones Steel Wheels 2. Milli Vanilli Girl You Know It’s True 3. Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation 1814 4. Tears For Fears The Seeds of Love 5. Fine Young Cannibals The Raw and the Cooked FILM Tonight: Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m.; $3/students Saturday: 21st Tournament of Animation, at I.V. Theater, 7,9,11 p.m.; $3 Sunday: King of the Children, at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m.; $3/students □ PERFORMANCE Which, too, Tonight: about. Music/Rally Phranc, as part of Take ■By Doug Arellane Back the Night, Storke Plaza, 7 p.m. ^ ¡§ ta ff Writer Phranc also dgjeys Free She says so on tie title Friday: Music 8th Annual World Music Festi new album, I Enjoy Being A val, at the Multicultural Center, 3 ^ s c r i b e s which is a cover of ah old Ro p.m.; Until Saturday; Free your average lesbian Jewis f ^ a*M ^ Poetry Ana Castillo, at the Women’s and Hammerstein number Yo Center, 12 p.m.; Free ger,” andgpsses it o^yitl for being a lesbian Jewish folks! Saturday:Afusic Udan Asih Gamelan kind of jinchalanceas ifllhe wHS & dance concert, at Campbell Hall, 8 Phranic$8ias a sense of humg p.m.; $10/students, $15/non-students P h ra n y “just your^ average sharp a! her flattop. -

Pipa Performance Reflects Agility, Ability

FEATURED Review: Pipa performance reflects agility, ability By Peter Jacobi | H-T Reviewer | April 2, 2017 An instrument that has a history of more than 2,000 years played in solo, played in combination with a classical string quartet and played as one among more than a dozen other members of an ensemble specializing in the avant-garde. The instrument, originated in China, is called pipa, part of the lute family that looks daunting to pluck and strum on. A full-house audience gathered Friday evening in the Buskirk-Chumley Theater to watch a virtuoso give sound to that daunting object of attention. Her name is Wu Man, a remarkable China-born and trained champion of the pipa, which can produce sweet and soft melodies along with forceful, even abrasive, sounds. Wu has lived the past quarter-century in the United States, spreading the word about her beloved pipa and commissioning new music for it. Here in Bloomington — thanks to support from the Lotus Education and Arts Foundation, the Indiana University Arts and Humanities Council and the IU Jacobs School of Music — Wu attached her artistry to the Vera Quartet, this school year’s graduate quartet in residence, and to David Dzubay’s influential New Music Ensemble. That made for a stellar lineup of musicians. The opening portion of Friday’s concert, however, belonged to Man alone. She performed three solo works that supremely tested her abilities. But from the first measures of “Dance of the Yi People,” based on tunes from a minority society that inhabits territory in southwestern China, one sensed that nothing technical could faze her. -

上海四重奏 2020年2月12日至13日 Board of Program Book Contact Directors Credits Us

上海四重奏 2020年2月12日至13日 BOARD OF PROGRAM BOOK CONTACT DIRECTORS CREDITS US James Reel Arizona Friends of Editor President Chamber Music Jay Rosenblatt Post Office Box 40845 Paul Kaestle Tucson, Arizona 85717 Vice-President Contributors Robert Gallerani Phone: 520-577-3769 Joseph Tolliver Holly Gardner Email: [email protected] Program Director Nancy Monsman Website: arizonachambermusic.org Helmut Abt Jay Rosenblatt Recording Secretary James Reel Operations Manager Cathy Anderson Wes Addison Advertising Treasurer Cathy Anderson USHERS Philip Alejo Michael Coretz Nancy Bissell Marvin Goldberg Barry & Susan Austin Kaety Byerley Paul Kaestle Lidia DelPiccolo Laura Cásarez Jay Rosenblatt Susan Fifer Michael Coretz Randy Spalding Marilee Mansfield Dagmar Cushing Allan Tractenberg Elaine Orman Bryan Daum Susan Rock Alan Hershowitz Design Jane Ruggill Tim Kantor Openform Barbara Turton Juan Mejia Diana Warr Jay Rosenblatt Printing Maurice Weinrobe & Trudy Ernst Elaine Rousseau West Press Randy Spalding VOLUNTEERS Paul St. John George Timson Dana Deeds Leslie Tolbert Beth Daum Ivan Ugorich Beth Foster Bob Foster Traudi Nichols Allan Tractenberg Diane Tractenberg 2 FROM THE PRESIDENT Our celebration of Beethoven’s 250th anniversary The argument in favor is that there is no single right continues this week with a pair of concerts by the way to play Beethoven, and each score offers a wealth Shanghai Quartet, presenting nearly one-third of of interpretive options. Each ensemble we present has Beethoven’s string quartet output. The Jerusalem its own distinctive approach to the music—free- Quartet will have its turn in April, and we’ll conclude wheeling, or elegant, or intense. Opening your ears to the festivities in the fall with double concerts by the multiple interpretations can lead you to hear new Auryn, Juilliard, and Pacifica Quartets. -

Silent Night the College Held a Brief, Yet Moving, Ceremony to Mark the Centennial of the Start of World Where: Singletary Center War I

OPERALEX.ORGbravo lex!FALL 2018 inside SOOP Little Red teaches kids to love opera, and obey SILENT their parents. Page 2 NIGHT Pulitzer Prize winner's moving story During the summer of 2014, I took a course at Merton College, Oxford. While I was there, Silent Night the college held a brief, yet moving, ceremony to mark the centennial of the start of World Where: Singletary Center War I. The ceremony was held outdoors in for the Arts, UK campus front of a list of names carved into a wall. The When: Nov. 9,10 at 7:30 p.m.; Nov. 11 at 2 p.m. names were those of young men from Merton Tickets: Call 859.257.4929 SUMMER DAYS College who died in the war. Some had been or visit We'll reap the benefit from students, others sons of staff and workers. We Taylor Comstock's summer www.SCFATickets.com all put poppies in our lapels and listened as the at Wolf Trap. Page 4 names were read out. The last one was the More on Page 3 name of a Merton student who had returned nLecture schedule for home to Germany to enlist, and like the others, other events n had fallen on the battlefield. A century later, all UK's Crocker is an expert on the Christmas truce the young men were together again as Merton See Page 3 Now you can support us when you shop at Amazon! Check out operalex.org FOLLOW UKOT on social media! lFacebook: UKOperaTheatre lTwitter: UKOperaTheatre lInstagram: ukoperatheatre Page 2 SOOPER OPERA! Little Red moves kids with music, story, acting SOOP – the Schmidt Opera Outreach Program – is performing Little Red’s Most Unusual Day in Kentucky schools this fall and the early reviews are promising. -

Grant Recognition Reception

Grant Recognition Reception April 16, 2013 Celebrating Research, Scholarship and Service Offi ce of Research and Sponsored Programs/University Advancement April 16th, 2013 Dear Colleagues On behalf of Vice President Jack Shannon and myself, I’m pleased to welcome you to the 1st Annual Grant Recognition Reception. During the calendar years 2011 and 2012, Montclair State University faculty and staff received over 185 grant awards through the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs and the Division of University Advancement. These grants were awarded by a growing list of external sponsors to include federal, state and local agencies, and private foundations, corporations and international organizations. In a time of increased competition for external funding for research and program support, the success of University faculty and staff in receiving external sponsorship to carry out their research, scholarly and service activities is a true testament to the innovative, creative and impactful work being conducted here at Montclair State. Our faculty and staff are forging collaborations across disciplines, institutions, communities and, increasingly, nations. They also are sharing ideas, maximizing creative energy and innovation to create new knowledge and address societal challenges. To all of those who have applied for and received support, we congratulate you and wish you the best for continued success. To those who will revise and resubmit, we applaud your persistence and determination and wish you better fortune going forward. To all of -

Making Chinese Choral Music Accessible in the United States: a Standardized Ipa Guide for Chinese-Language Works

MAKING CHINESE CHORAL MUSIC ACCESSIBLE IN THE UNITED STATES: A STANDARDIZED IPA GUIDE FOR CHINESE-LANGUAGE WORKS by Hana J. Cai Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Carolann Buff, Research Director __________________________________________ Dominick DiOrio, Chair __________________________________________ Gary Arvin __________________________________________ Betsy Burleigh September 8, 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 Hana J. Cai For my parents, who instilled in me a love for music and academia. Acknowledgements No one accomplishes anything alone. This project came to fruition thanks to the support of so many incredible people. First, thank you to the wonderful Choral Conducting Department at Indiana University. Dr. Buff, thank you for allowing me to pursue my “me-search” in your class and outside of it. Dr. Burleigh, thank you for workshopping my IPA so many times. Dr. DiOrio, thank you for spending a semester with this project and me, entertaining and encouraging so much of my ridiculousness. Second, thank you to my amazing colleagues, Grant Farmer, Sam Ritter, Jono Palmer, and Katie Gardiner, who have heard me talk about this project incessantly and carried me through the final semester of my doctorate. Thank you, Jingqi Zhu, for spending hours helping me to translate English legalese into Chinese. Thank you to Jeff Williams, for the last five years. Finally, thank you to my family for their constant love and support. -

Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello

Monday Evening, December 11, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello Bell and Drum: Percussion Music From China GUO WENJING (b. 1956) Parade (2003) SAE HASHIMOTO EVAN SADDLER DAVID YOON ZHOU LONG (b. 1953) Wu Ji (2006) CHRISTOPHER STAKNYS, Piano BENJAMIN CORNOVACA LEO SIMON LEI LIANG (b. 1972) Inkscape (2014) DANIEL PARKER, Piano TYLER CUNNINGHAM JAKE DARNELL OMAR EL-ABIDIN EUIJIN JUNG Intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. CHOU WEN-CHUNG (b. 1923) Echoes From the Gorge (1989) Prelude: Exploring the modes Raindrops on Bamboo Leaves Echoes From the Gorge, Resonant and Free Autumn Pond Clear Moon Shadows in the Ravine Old Tree by the Cold Spring Sonorous Stones Droplets Down the Rocks Drifting Clouds Rolling Pearls Peaks and Cascades Falling Rocks and Flying Spray JOSEPH BRICKER TAYLOR HAMPTON HARRISON HONOR JOHN MARTIN THENELL TAN DUN (b. 1957) Elegy: Snow in June (1991) ZLATOMIR FUNG, Cello OMAR EL-ABIDIN BENJAMIN CORNOVACA TOBY GRACE LEO SIMON Performance time: Approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission Notes on the Program Scored for six Beijing opera gongs laid flat on a table, Parade is an exhilarating work by Jay Goodwin that amazes both with its sheer difficulty to perform and with the incredible array of dif - “In studying non-Western music, one ferent sounds that can be coaxed from must consider the character and tradition what would seem to be a monochromatic of its culture as well as all the inherent selection of instruments. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Betsy Aldredge Media Relations Specialist

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Betsy Aldredge Media Relations Specialist 914-251-6959 [email protected] PURCHASE COLLEGE LECTURER DU YUN WINS PULITZER PRIZE FOR HER OPERATIC WORK Angel’s Bone is About Human Trafficking Purchase, NY, [April 12, 2017]: Purchase College, SUNY is pleased to announce that Du Yun, a lecturer in the School of the Arts, has been awarded a Pulitzer Prize in music for her groundbreaking operatic work about human trafficking, Angel’s Bone, which was first produced at the Protoype Festival, 3LD Arts and Technology Center, New York City in January 2016. The piece includes a libretto by Royce Vavrek. The Pulitzer jury described it as a “bold operatic work that integrates vocal and instrumental elements and a wide range of styles into a harrowing allegory for human trafficking in the modern world.” Du Yun, who is known for her cutting edge work, told NPR that “When we look at human trafficking, we always think that it's far away from us. We all have our own narrative of what human trafficking is supposed to be, but if you do a little research, human trafficking happens, in many different forms and shapes, right in our backyard." Born and raised in Shanghai, China, and currently based in New York, Du Yun is a Pulitzer Prize– winning composer, multi-instrumentalist, performance artist, activist, and curator for new music, working at the intersection of orchestral, opera, and chamber music, theatre, cabaret, oral tradition, public performance, sound installation, electronics, and noise. Hailed by The New York Times as a leading figure in China’s new generation of composers, Du Yun’s music is championed by some of today’s finest performing artists, ensembles, orchestras, and organizations. -

The Shanghai Quartet with Eugenia Zukerman

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 10-30-1995 The hS anghai Quartet with Eugenia Zukerman Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "The hS anghai Quartet with Eugenia Zukerman" (1995). Music Department Concert Programs. 590. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/590 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CONCERT SERIES THE SHANGHAI QUARTET Quartet-in-Residence Weigang Li, violin Yi-Wen Jiang, violin Honggang Li, viola James Wilson, cello ~ith Guest Artist Eugenia Zukerman, flute October 30, 1995, 8:15 PM Cannon Memorial Chapel An extraordinary flutist whose communicative gifts extend to other media, Eugenia Zukerman is in great demand worldwide as she appears regularly with orchestras, in solo and duo recitals, and in chamber music ensembles in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East over the past twenty-five years. Ms. Zukerman is also a successful writer and television commentator. As a recording artist, Ms. Zukerman is embarlcing on a series for Delos, of which the first album, Music for a Sunday Morning, has just been released. In this recording, Ms. Zukerman teams up with her frequent concert collaborators, the Shanghai Quartet and keyboardist Anthony Newman for a delightful program including music of Mozart, Bach, American composers Amy Beach and Arthur Foote, and finally South American composer Alberto Ginastera. -

Views About His Own Opera

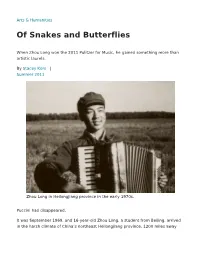

Arts & Humanities Of Snakes and Butterflies When Zhou Long won the 2011 Pulitzer for Music, he gained something more than artistic laurels. By Stacey Kors | Summer 2011 Zhou Long in Heilongjiang province in the early 1970s. Puccini had disappeared. It was September 1969, and 16-year-old Zhou Long, a student from Beijing, arrived in the harsh climate of China’s northeast Heilongjiang province, 1200 miles away from his family. His father was a painter and fine arts professor, and his mother a Western-style voice teacher. Zhou ’93GSAS, who had taken lessons in voice and piano, had been preparing for conservatory study. Now, he was assigned to drive a tractor, grow crops, and spend hours every day hauling heavy sacks of beans and wheat down a narrow gangplank to the granary. During the long winters, the winds roared and the temperatures averaged nine degrees Fahrenheit, sending the inhabitants into underground dwellings. This was the Heilongjiang Production and Construction Corps, a state farm near Hegang City. Zhou desperately missed his family and his music, and tried to find solace in the only melodies allowed on the farm: revolutionary songs, which he taught himself to play on his accordion. “I played some operas from the Cultural Revolution, too,” he says. “But back home I had played art songs and listened to Puccini.” But Puccini was gone. The Cultural Revolution, Mao’s brutal program of socialist orthodoxy that began in 1966, had expunged many things that smacked of the indulgent, capitalist West. Hundreds of thousands of city youth, like Zhou, left their families for the countryside, where they learned agricultural skills through manual labor.