Views About His Own Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai Quartet 2020-21 Biography

SHANGHAI QUARTET 2020-21 BIOGRAPHY Over the past thirty-seven years the Shanghai Quartet has become one of the world’s foremost chamber ensembles. The Shanghai’s elegant style, impressive technique, and emotional breadth allows the group to move seamlessly between masterpieces of Western music, traditional Chinese folk music, and cutting-edge contemporary works. Formed at the Shanghai Conservatory in 1983, soon after the end of China’s harrowing Cultural Revolution, the group came to the United States to complete its studies; since then the members have been based in the U.S. while maintaining a robust touring schedule at leading chamber-music series throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. Recent performance highlights include performances at Carnegie Hall, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Freer Gallery (Washington, D.C.), and the Festival Pablo Casals in France, and Beethoven cycles for the Brevard Music Center, the Beethoven Festival in Poland, and throughout China. The Quartet also frequently performs at Wigmore Hall, the Budapest Spring Festival, Suntory Hall, and has collaborations with the NCPA and Shanghai Symphony Orchestras. Upcoming highlights include the premiere of a new work by Marcos Balter for the Quartet and countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo for the Phillips Collection, return performances for Maverick Concerts and the Taos School of Music, and engagements in Los Angeles, Syracuse, Albuquerque, and Salt Lake City. Among innumberable collaborations with eminent artists, they have performed with the Tokyo, Juilliard, and Guarneri Quartets; cellists Yo-Yo Ma and Lynn Harrell; pianists Menahem Pressler, Peter Serkin, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, and Yuja Wang; pipa virtuoso Wu Man; and the vocal ensemble Chanticleer. -

Pipa Performance Reflects Agility, Ability

FEATURED Review: Pipa performance reflects agility, ability By Peter Jacobi | H-T Reviewer | April 2, 2017 An instrument that has a history of more than 2,000 years played in solo, played in combination with a classical string quartet and played as one among more than a dozen other members of an ensemble specializing in the avant-garde. The instrument, originated in China, is called pipa, part of the lute family that looks daunting to pluck and strum on. A full-house audience gathered Friday evening in the Buskirk-Chumley Theater to watch a virtuoso give sound to that daunting object of attention. Her name is Wu Man, a remarkable China-born and trained champion of the pipa, which can produce sweet and soft melodies along with forceful, even abrasive, sounds. Wu has lived the past quarter-century in the United States, spreading the word about her beloved pipa and commissioning new music for it. Here in Bloomington — thanks to support from the Lotus Education and Arts Foundation, the Indiana University Arts and Humanities Council and the IU Jacobs School of Music — Wu attached her artistry to the Vera Quartet, this school year’s graduate quartet in residence, and to David Dzubay’s influential New Music Ensemble. That made for a stellar lineup of musicians. The opening portion of Friday’s concert, however, belonged to Man alone. She performed three solo works that supremely tested her abilities. But from the first measures of “Dance of the Yi People,” based on tunes from a minority society that inhabits territory in southwestern China, one sensed that nothing technical could faze her. -

Silent Night the College Held a Brief, Yet Moving, Ceremony to Mark the Centennial of the Start of World Where: Singletary Center War I

OPERALEX.ORGbravo lex!FALL 2018 inside SOOP Little Red teaches kids to love opera, and obey SILENT their parents. Page 2 NIGHT Pulitzer Prize winner's moving story During the summer of 2014, I took a course at Merton College, Oxford. While I was there, Silent Night the college held a brief, yet moving, ceremony to mark the centennial of the start of World Where: Singletary Center War I. The ceremony was held outdoors in for the Arts, UK campus front of a list of names carved into a wall. The When: Nov. 9,10 at 7:30 p.m.; Nov. 11 at 2 p.m. names were those of young men from Merton Tickets: Call 859.257.4929 SUMMER DAYS College who died in the war. Some had been or visit We'll reap the benefit from students, others sons of staff and workers. We Taylor Comstock's summer www.SCFATickets.com all put poppies in our lapels and listened as the at Wolf Trap. Page 4 names were read out. The last one was the More on Page 3 name of a Merton student who had returned nLecture schedule for home to Germany to enlist, and like the others, other events n had fallen on the battlefield. A century later, all UK's Crocker is an expert on the Christmas truce the young men were together again as Merton See Page 3 Now you can support us when you shop at Amazon! Check out operalex.org FOLLOW UKOT on social media! lFacebook: UKOperaTheatre lTwitter: UKOperaTheatre lInstagram: ukoperatheatre Page 2 SOOPER OPERA! Little Red moves kids with music, story, acting SOOP – the Schmidt Opera Outreach Program – is performing Little Red’s Most Unusual Day in Kentucky schools this fall and the early reviews are promising. -

Making Chinese Choral Music Accessible in the United States: a Standardized Ipa Guide for Chinese-Language Works

MAKING CHINESE CHORAL MUSIC ACCESSIBLE IN THE UNITED STATES: A STANDARDIZED IPA GUIDE FOR CHINESE-LANGUAGE WORKS by Hana J. Cai Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Carolann Buff, Research Director __________________________________________ Dominick DiOrio, Chair __________________________________________ Gary Arvin __________________________________________ Betsy Burleigh September 8, 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 Hana J. Cai For my parents, who instilled in me a love for music and academia. Acknowledgements No one accomplishes anything alone. This project came to fruition thanks to the support of so many incredible people. First, thank you to the wonderful Choral Conducting Department at Indiana University. Dr. Buff, thank you for allowing me to pursue my “me-search” in your class and outside of it. Dr. Burleigh, thank you for workshopping my IPA so many times. Dr. DiOrio, thank you for spending a semester with this project and me, entertaining and encouraging so much of my ridiculousness. Second, thank you to my amazing colleagues, Grant Farmer, Sam Ritter, Jono Palmer, and Katie Gardiner, who have heard me talk about this project incessantly and carried me through the final semester of my doctorate. Thank you, Jingqi Zhu, for spending hours helping me to translate English legalese into Chinese. Thank you to Jeff Williams, for the last five years. Finally, thank you to my family for their constant love and support. -

Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello

Monday Evening, December 11, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello Bell and Drum: Percussion Music From China GUO WENJING (b. 1956) Parade (2003) SAE HASHIMOTO EVAN SADDLER DAVID YOON ZHOU LONG (b. 1953) Wu Ji (2006) CHRISTOPHER STAKNYS, Piano BENJAMIN CORNOVACA LEO SIMON LEI LIANG (b. 1972) Inkscape (2014) DANIEL PARKER, Piano TYLER CUNNINGHAM JAKE DARNELL OMAR EL-ABIDIN EUIJIN JUNG Intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. CHOU WEN-CHUNG (b. 1923) Echoes From the Gorge (1989) Prelude: Exploring the modes Raindrops on Bamboo Leaves Echoes From the Gorge, Resonant and Free Autumn Pond Clear Moon Shadows in the Ravine Old Tree by the Cold Spring Sonorous Stones Droplets Down the Rocks Drifting Clouds Rolling Pearls Peaks and Cascades Falling Rocks and Flying Spray JOSEPH BRICKER TAYLOR HAMPTON HARRISON HONOR JOHN MARTIN THENELL TAN DUN (b. 1957) Elegy: Snow in June (1991) ZLATOMIR FUNG, Cello OMAR EL-ABIDIN BENJAMIN CORNOVACA TOBY GRACE LEO SIMON Performance time: Approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission Notes on the Program Scored for six Beijing opera gongs laid flat on a table, Parade is an exhilarating work by Jay Goodwin that amazes both with its sheer difficulty to perform and with the incredible array of dif - “In studying non-Western music, one ferent sounds that can be coaxed from must consider the character and tradition what would seem to be a monochromatic of its culture as well as all the inherent selection of instruments. -

Music for Piano

ECHOES OF CHINA Contemporary Piano Music Zhou Long Doming Lam Alexina Louie Tan Dun Chen Yi Susan Chan, Piano Echoes of China Doming Lam (b. 1926): Alexina Louie (b. 1949): Music for Piano (1982) Contemporary Piano Music Lamentations of Lady Chiu-Jun (1964) Alexina Louie is one of Canada’s I am honoured to collaborate with these renowned living Composer’s Note Born in 1926 in Macau, Doming Lam most highly regarded and most Chinese composers and to record their music, which is a former composer-in-residence often performed composers. Her mixes old and new, East and West – elements that Pianobells was commissioned by Susan Chan and first of the University of Hong Kong and desire for self-expression, her resonate with me. The commissioning project with Chen performed on 20th April 2012 at the Musica Nova concert the winner of 2010 and 2012 CASH recognizable sound world, as well Yi and Zhou Long resulted in the birth of two stunning of the UKMC Conservatory of Music and Dance. The Golden Sail Music Awards. He is the as her explorations of Asian music, works that bring together eastern and western aesthetics, commission was made possible by May Lui, the Portland Founding Director of the Asian art, and philosophy, have contributed and their cultures of origin. Heartfelt thanks go to these State University Foundation, the Regional Arts & Culture Composers’ League. Lam studied to the development of her unique composers who make the world smaller and more Council, and Oregon Arts Commission. music in Canada, the United States musical voice. Louie’s work is beautiful, and to all who contributed to this project. -

An Annotated Bibliography and Performance Commentary of The

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-1-2016 An Annotated Bibliography and Performance Commentary of the Works for Concert Band and Wind Orchestra by Composers Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music 1993-2015, and a List of Their Works for Chamber Wind Ensemble Stephen Andrew Hunter University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Music Education Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Hunter, Stephen Andrew, "An Annotated Bibliography and Performance Commentary of the Works for Concert Band and Wind Orchestra by Composers Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music 1993-2015, and a List of Their Works for Chamber Wind Ensemble" (2016). Dissertations. 333. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/333 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY OF THE WORKS FOR CONCERT BAND AND WIND ORCHESTRA BY COMPOSERS AWARDED THE PULITZER PRIZE IN MUSIC 1993-2015, AND A LIST OF THEIR WORKS FOR CHAMBER WIND ENSEMBLE by Stephen Andrew Hunter A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Catherine A. Rand, Committee Chair Associate Professor, School of Music ________________________________________________ Dr. -

CARMINA BURANA Thursday, March 28 at 7 P.M

CLASSICAL SERIES 2018/19 SEASON CARMINA BURANA Thursday, March 28 at 7 p.m. Friday and Saturday, March 29-30 at 8 p.m. Sunday, March 31 at 2 p.m. RYAN McADAMS, guest conductor SARAH KIRKLAND Something for the Dark SNIDER AUGUSTA READ EOS (Goddess of the Dawn), a Ballet for Orchestra THOMAS I. Dawn V. Spring Rain II. Daybright and Firebright VI. Golden Chariot III. Shimmering VII. Sunlight IV. Dreams and Memories INTERMISSION ORFF Carmina burana Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World) Part I. Primo vere (In Springtime) Uf dem anger (On the lawn) Part II. In taberna (In the Tavern) Part III. Cour d’amours (The Court of Love) Blanziflor et Helena (Blanchefleur and Helen) Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi JENNIFER ZETLAN, soprano | NICHOLAS PHAN, tenor | HUGH RUSSELL, baritone KANSAS CITY SYMPHONY CHORUS, CHARLES BRUFFY, chorus director LAWRENCE CHILDREN’S CHOIR, CAROLYN WELCH, artistic director *See program insert for Carmina Burana text and translation. The 2018/19 season is generously sponsored by Friday’s concert sponsored by SHIRLEY and BARNETT C. HELZBERG, JR. JIM AND JUDY HEETER Saturday’s concert sponsored by The Classical Series is sponsored by CAROL AND JOHN KORNITZER Guest Conductor Ryan McAdams sponsored by ANN MARIE TRASK Additional support provided by R. Crosby Kemper, Jr. Fund Podcast available at kcsymphony.org KANSAS CITY SYMPHONY 43 Kansas City Symphony PROGRAM NOTES By Ken Meltzer SARAH KIRKLAND SNIDER (b. 1973) Something for the Dark (2016) 12 minutes Piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, chimes, crotales, cymbals, glockenspiel, marimba, sleigh bells, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tom-toms, triangle, vibraphone, harp, piano, celesta and strings. -

Tools of the Trade #62 Songlines Feature

° tOOLS OF THE tRaDe° ° the pipa ° thousand varieties of folk Ming dynasty took over, the pipa – associated music still thrive in China’s with foreign culture – was removed from its villages, but after 60 years of court position and took root in the provinces communism, Red Guardism, instead. And that led to the different schools of and rampant capitalism, China’s playing which persist to this day, with Shanghai Acourt tradition has withered on the vine. as the dominant focus. Styles were passed Belatedly, the country’s rulers have now woken down orally, within families. up to the musical heritage they have all but lost. Hence the eagerness with which they are now War and peace promoting young virtuosi on the pipa, which What’s remarkable is that, despite the historically spans both court and folk traditions, considerable changes in both the instrument Tools of The Trade without belonging entirely in either. And hence and how it’s played – moving from a horizontal the close attention Western musicians are to a near-vertical position – the main elements paying to the new soundworlds being opened in the repertoire have hardly changed over four up through cross-cultural collaborations led centuries. The pipa piece which most Chinese by the instrument’s most celebrated exponent, know today is ‘Ambush From Ten Sides,’ a Wu Man. “The shape and the sound of the rousing evocation of the Han founder’s victory pipa is elegant, yet also dramatic,” she says. over the warlord of Chu, complete with the “And its personality is strong – you can express sounds of drumming hooves, screaming The yourself in many ways.” soldiers and clashing weapons, and first As a soloist, the effects Wu Man can published in 1662. -

JIAO, WEI, D.M.A. Chinese and Western Elements in Contemporary

JIAO, WEI, D.M.A. Chinese and Western Elements in Contemporary Chinese Composer Zhou Long’s Works for Solo Piano Mongolian Folk-Tune Variations, Wu Kui, and Pianogongs. (2014) Directed by Dr. Andrew Willis. 136 pp. Zhou Long is a Chinese American composer who strives to combine traditional Chinese musical techniques with modern Western compositional ideas. His three piano pieces, Mongolian Folk Tune Variations, Wu Kui, and Pianogongs each display his synthesis of Eastern and Western techniques. A brief cultural, social and political review of China throughout Zhou Long’s upbringing will provide readers with a historical perspective on the influence of Chinese culture on his works. Study of Mongolian Folk Tune Variations will reveal the composers early attempts at Western structure and harmonic ideas. Wu Kui provides evidence of the composer’s desire to integrate Chinese cultural ideas with modern and dissonant harmony. Finally, the analysis of Pianogongs will provide historical context to the use of traditional Chinese percussion instruments and his integration of these instruments with the piano. Zhou Long comes from an important generation of Chinese composers including, Chen Yi and Tan Dun, that were able to leave China achieve great success with the combination of Eastern and Western ideas. This study will deepen the readers’ understanding of the Chinese cultural influences in Zhou Long’s piano compositions. CHINESE AND WESTERN ELEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE COMPOSER ZHOU LONG’S WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO MONGOLIAN FOLK-TUNE VARIATIONS, WU KUI, AND PIANOGONGS by Wei Jiao A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2014 Approved by _________________________________ Committee Chair © 2014 Wei Jiao APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

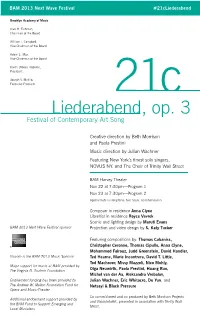

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

Music from China & Talujon Tales from the Cave

Williams College Department of Music Music From China & Talujon Tales from the Cave PROGRAM NOTES Mount a Long Wind (2004) ZHOU LONG For pipa, flute, erhu, zheng, percussion Mount a Long Wind is dedicated to Music From China on their 20th anniversary. It is inspired by Tang dynasty poet Li Bai's “The Hard Road” (One of Three). The music reflects the vivid imagery of the poem. Textured waves accompanied by strong rhythmic chords on pipa and zheng symbolize a journey -- to mount a long wind and break the heavy waves. As the music briefly calms, a vigorous rhythmic section ensues which shapes a scene of driving the dragon boat. In the middle section, a melody played by erhu with harmonics on pipa and glissandi on zheng evoke sounds of nature. A recapitulation of the vigorous rhythmic section brings the music to a celebratory climax. * * * * * Zhou Long is internationally recognized for creating a unique body of music that brings together the aesthetic concepts and musical elements of East and West. Winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for his first opera, Madame White Snake, Dr. Zhou also received the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, and the 2012-2013 Elise Stoeger Prize from Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society. He has been two-time recipient of commissions from the Koussevitzky, Fromm Music Foundations, Meet the Composer, Chamber Music America, and the New York State Council on the Arts. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundations, and the New York Foundation for the Arts.