University of Pretoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

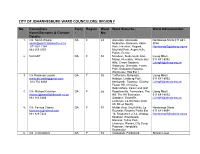

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Are Johannesburg's Peri-Central Neighbourhoods Irremediably 'Fluid'?

Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams Claire Bénit-Gbaffou To cite this version: Claire Bénit-Gbaffou. Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Lo- cal leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams. Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds), Changing Space, Changing City., Wits University Press, pp.252-268, 2014, 10.18772/22014107656.17. hal-02780496 HAL Id: hal-02780496 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02780496 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 13 Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams CLAIRE BÉNIT-gbAFFOU Johannesburg’s inner city is a convenient symbol in contemporary city culture for urban chaos, unpredictability, endless mobility and undecipherable change – as emblematised by portrayals of the infamous Hillbrow in novels and movies (Welcome to our Hillbrow, Room 207, Zoo City, Jerusalema)1 and in academic literature (Morris 1999; Simone 2004). Inner-city neighbourhoods in the CBD and on its immediate fringe (or ‘peri-central’ areas) currently operate as ports of entry into South Africa’s economic capital, for both national and international migrants. -

Public Announcement from City Power Johannesburg You Are Hereby

City Power Johannesburg 40 Heronmere Road PO Box 38766 Tel +27(0) 11 490 7000 Reuven Booysens Fax +27(0) 11 490 7590 Johannesburg 2016 www.citypower.co.za Public Announcement from City Power Johannesburg You are hereby notified of a planned power interruption on Monday the 10th of July 2017 at 22h00 and the following areas will be affected: Benrose Benrose Ext 1, 10, 11, 12, Cleveden and Cleveden 13, 14, 15, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Ext 7 8, 9 Denver Denver Ext 1, 10, 11, 12, Elcedes 13, 15, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9 Heriodtdale Ext 10,1,12, Jeppestown Jeppestown South 13, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Malvern and Malvern Ext Reynolds View Spes Bona 1, 3 Wolhuter Kensington Kensington Ext 11, 12, 13, 3, 4, 8, 9 Oospoort Ext 1 South Kensington The Gables and The Gabels Ext 1, 2, 3, 4 Bramley & Bramley Ext 1 Bramley Park Bramley View Ext 2, 8 Crystal Gardens A.H Gresswold Kew & Kew Ext 1 Lyndhurst & Lyndhurst Raumaris Park Whitney Gardens Ext 10, Ext 1, 2 14,1, 15, 2, 3, 4, 9 Wynberg Alexandra Ext 15, 18, 36, Bramley Manor 8 Bramley View Bramley View Ext 1, 11, Casey Park 12, 14, 15, 16, 2, 4, 6, 8,9 Corlett Gardens & Colett Dorelan Dunsevern & Dunsevern Gardens Ext 1, 2, 3 Ext 1, 4 Fairmount & Fairmount Formain Glenhazel & Glenhazel Ext 2 Ext 10, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9 Highlands North & Highlands North Ext 2, 3, Lombardy East & West Highlands North Ext 3, 9 4, 6, 6, 9 Longmeadow Business Percelia Estate & Raedene Estate & Estate Ext 10, 2 Percelia Estate Ext 1, 2 Raedene Estate Rembrandt Park & Rembrandt Ridge Rouxville Rembrandt Park Ext 10, 11, 12, 4, 5, 6, 9 Sunningdale -

Department of Human Settlements Government Gazette No

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 671 NO. 671 NO. Priority Housing Development Areas Department of Human Settlements Housing Act (107/1997): Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas HousingDevelopment Priority Proposed (107/1997): Act Government Gazette No.. I, NC Mfeketo, Minister of Human Settlements herewith gives notice of the proposed Priority Housing Development Areas (PHDAs) in terms of Section 7 (3) of the Housing Development Agency Act, 2008 [No. 23 of 2008] read with section 3.2 (f-g) of the Housing Act (No 107 of 1997). 1. The PHDAs are intended to advance Human Settlements Spatial Transformation and Consolidation by ensuring that the delivery of housing is used to restructure and revitalise towns and cities, strengthen the livelihood prospects of households and overcome apartheid This gazette isalsoavailable freeonlineat spatial patterns by fostering integrated urban forms. 2. The PHDAs is underpinned by the principles of the National Development Plan (NDP) and allied objectives of the IUDF which includes: DEPARTMENT OFHUMANSETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT 2.1. Spatial justice: reversing segregated development and creation of poverty pockets in the peripheral areas, to integrate previously excluded groups, resuscitate declining areas; 2.2. Spatial Efficiency: consolidating spaces and promoting densification, efficient commuting patterns; STAATSKOERANT, 2.3. Access to Connectivity, Economic and Social Infrastructure: Intended to ensure the attainment of basic services, job opportunities, transport networks, education, recreation, health and welfare etc. to facilitate and catalyse increased investment and productivity; 2.4. Access to Adequate Accommodation: Emphasis is on provision of affordable and fiscally sustainable shelter in areas of high needs; and Departement van DepartmentNedersettings, of/Menslike Human Settlements, 2.5. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Inner City Eastern Gateway Urban Development Framework & Implementation Plan Report | 2016

INNER CITY EASTERN GATEWAY URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK & IMPLEMENTATION PLAN REPORT | 2016 Prepared for: Prepared by: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG & OSMOND LANGE ARCHITECTS JOHANNESBURG DEVELOPMENT & PLANNERS (Pty) Ltd AGENCY Unit 3, Ground Floor The Bus Factory 3 Melrose Boulevard No. 3 President Street Melrose Arch Newtown 2196 Johannesburg [t]: 011 994 4300 [t]: 011 688 7851 [f]: 011 684 1436 [f]: 011 688 7899 email: [email protected] In Collaboration with: URBAN- ECON , HATCH GOBA, U SPACE & TANYA ZACK DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8.0 URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 8.1 VISION PLAN 2.0. INTRODUCTION 8.2 LAND USE 8.2.1. PROPOSED LAND USES 3.0. STATUS QUO 8.2.2. ZONING 3.1 REGIONAL CONTEXT 8.3 PUBLIC ENVIRONMENT 3.1.1 LOCALITY 8.3.1. PUBLIC REALM 3.1.2 GAUTENG CITY REGION CONTEXT 8.3.2 MOVEMENT NETWORK 3.1.3 METROPOLITAN CONTEXT 8.3.3. PARKS & GREEN SPACES 3.1.4 THE ROLE OF JOHANNESBURG INNER CITY 8.4 BUILT FORM 3.1.5 AEROTROPOLIS CONTEXT 8.4.1. HEIGHT AND GRAIN GUIDELINES 8.4.2. STREET EDGE GUIDELINES 8.5 HOUSING 3.2 STUDY AREA 8.5.1. ASSUMPTIONS: NUMBER OF HOUSEHOLDS THAT 3.2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT REQUIRE HOUSING INTERVENTION I TOPOGRAPHY 8.5.2 ESTIMATES OF HOUSING NEED II OPEN SPACE SYSTEM 8.5.3 POSSIBLE INTERVENTIONS – HOUSING FORMS 3.2.2 BUILT ENVIRONMENT 8.5.4 APPLYING ICHIP IN EASTERN GATEWAY i LAND USE 8.5.5 LOGIC FOR HOUSING INTERVENTION II ZONING 8.5.6 ICHIP PRIORITY HOUSING PRECINCTS III BUILT FORM 8.5.7 HOUSING DELIVERY REQUIREMENTS iv HERITAGE 8.5.8 PROPOSED HOUSING INTERVENTIONS v TRANSPORT & TRAFFIC 8.5.9 PROPOSED HOUSING TYPOLOGIES 3.2.3 SOCIO- ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT 8.6 SOCIAL FACILITIES i POPULATION 8.6.1. -

Infrastructures of Property and Debt: Making Affordable Housing, Race and Place in Johannesburg

Infrastructures of Property and Debt: making affordable housing, race and place in Johannesburg A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Siân Butcher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisors: Helga Leitner and Eric Sheppard Department: Geography, Environment and Society July 2016 ©2016 by Siân Butcher Acknowledgements This dissertation is not only about debt, but has been made possible through many debts, but also gifts of various kinds. I want to start by thanking the following for their material support of my graduate study at the University of Minnesota (UMN), my dissertation research and my writing time. Institutionally, my homes have been the department of Geography, Environment and Society (GES) and the Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change (ICGC). ICGC supported me for two years in partnership with the Center for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) through the generous ICGC-Mellon Scholar fellowship. Pre-dissertation fieldwork between 2010-2011 was supported by GES, ICGC, the York-Wits Global Suburbanisms project, and the Social Science Research Council’s Dissertation Proposal Development Fellowship (SSRC DPDF). Dissertation fieldwork in Johannesburg was made possible by UMN’s Global Spotlight Doctoral Dissertation International Research Grant (2012- 2013) and the immeasurable support of friends and family. My two years of writing was enabled by a semester’s residency at the CHR at UWC in Cape Town; a Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship from the University of Minnesota (2014-5), and a home provided by my partner Trey Smith and then my mother, Sue Butcher. -

Turffontein Precinct Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan Report Phase 3

tsica – the significance of cultural history Turffontein Precinct Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan Report Phase 3 Turffontein Development Corridor Prepared for: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG Johannesburg Development Agency No 3 Helen Joseph Street The Bus Factory Newtown Johannesburg, 2000 PO Box 61877 Marshalltown 2107 Tel +27(0) 11 688 7851 Fax +27(0) 11 688 7899/6 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Ms. Yasmeen Dinath Tel +27(0) 11 688 7800 E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by: tsica heritage consultants & Clive Chipkin,Jacques Stoltz, Piet Snyman, Ngonidzashe Mangoro, Johann le Roux 41 5th Avenue Westdene 2092 Johannesburg tel/fax 011 477 8821 [email protected] Date: 26 May 2016 2 Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Glossary of terms Biodiversity An area defined as such by the City of Johannesburg area Conservation As defined in the NHRA means the protection, maintenance, preservation and sustainable use of places or objects so as to safeguard their cultural significance Conservation Heritage areas officially designated as such by the area Heritage Resources Authority in consultation with the City of Johannesburg Conservation A policy aimed at the management of a heritage Management resource and that is approved by the Heritage Plan Resources Authority setting out the manner in which the conservation of a site, place or object will be achieved Corridors of Spatially -

Johannesburg Street Traders Halt Operation Clean Sweep

Johannesburg Street Traders Halt Operation Clean Sweep September 2014 WIEGO LAW & INFORMALITY PROJECT Johannesburg Street Traders Halt Operation Clean Sweep Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing is a global network focused on securing livelihoods for the working poor, especially women, in the informal economy. We believe all workers should have equal economic opportunities and rights. WIEGO creates change by building capacity among informal worker organizations, expanding the knowledge base about the informal economy and influencing local, national and international policies. WIEGO’s Law & Informality project analyzes how informal workers’ demands for rights and protections can be transformed into law. The Social Law Project (SLP), based at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, is a dynamic research and training unit staffed by a core of research and training professionals specialising in labour and social security law. It aims to promote sustainable workplace democracy by: • conducting (applied) research supportive of the development of employment rights and rights-based culture in the workplace. • providing training services in labour and social security law with a focus on client-specific training need. Publication date: September 2014 Please cite this publication as: Social Law Project. 2014. Johannesburg Street Traders Halt Operation Clean Sweep. WIEGO Law and Informality Resources. Cambridge, MA, USA: WIEGO. Published by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee – Company No. 6273538, Registered Charity No. 1143510 WIEGO Secretariat WIEGO Limited Harvard Kennedy School, 521 Royal Exchange 79 John F. Kennedy Street Manchester, M2 7EN Cambridge, MA 02138, USA United Kingdom www.wiego.org Copyright © WIEGO. -

SAARF OHMS 2006 Database Layout

SAARF OUTDOOR MEASUREMENT SURVEY PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL Outdoor Database Layout South Africa (GAUTENG & KWAZULU-NATAL) August 2007 FILES FOR COMPUTER BUREAUX Prepared for: - South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) Prepared by: - Nielsen Media Research and Nielsen Outdoor Copyright Reserved Confidential 1 The following document describes the content of the database files supplied to the computer bureaux. The database includes four input files necessary for the Outdoor Reach and Frequency algorithms: 1. Outdoor site locations file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Sites) 2. Respondent file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Respondents) 3. Board Exposures file (2 – Boards Exposure file) 4. Smoothed Board Impressions file (2 – Smoothed Board Impressions File) The data files are provided in a tab separated format, where all files are Window zipped. 1) Outdoor Site Locations File Format: The file contains the following data fields with the associated data types and formats: Data Field Max Data type Data definitions Extra Comments length (where necessary) Media Owner 20 character For SA only 3 owners: Clear Channel, Outdoor Network, Primedia Nielsen Outdoor 6 integer Up to a 6-digit unique identifier for Panel ID each panel Site type 20 character 14 types. (refer to last page for types) Site Size 10 character 30 size types (refer to last pages for sizes) Illumination hours 2 integer 12 (no external illumination) 24 (sun or artificially lit at all times) Direction facing 2 Character N, S, E, W, NE, NW, SE, SW Province 25 character 2 Provinces – Gauteng , Kwazulu- -

Our Areas of Finance Our Branches

OUR BRANCHES OUR AREAS OF FINANCE GAUTENG GAUTENG Johannesburg Pretoria JOHANNESBURG • Hillbrow • Rosettenville 12th Floor, Libridge Building 8th Floor, Olivetti House • Auckland Park • Jeppestown • Rouxville 25 Ameshoff street 100 Pretorius Street • Bellevue • Johannesburg CBD • Selby Braamfontein Cnr Pretorius & Schubart Str • Bellevue East • Joubert Park • Springs CBD Johannesburg, 2001 Pretoria, 0117 • Benoni • Judiths Paarl • Troyeville +27 (10) 595 9000 +27 (10) 595 9000 • Berea • Kempton Park CBD • Turf Club WELCOME • Bertrams • Kenilworth • Turffontein • Bezuidenhout KWAZULU NATAL • Kensington • Westdene Valley • Krugersdorp • Witpoortjie 27th Floor, Embassy Building • Boksburg North • La Rochelle • Yeoville TO TUHF 199 Anton Lembede Street • Braamfontein Durban, 4001 • Langbaagte • Brakpan +27 (31) 306 5036 • Lorentzville PRETORIA • Brixton • Marshall Town • Arcadia • City and Suburban • Melville • Capital Park CBD EASTERN CAPE • Doornfontein • New Doornfontein • Gezina CBD 2nd Floor, BCX Building • Fairview • Newtown • Hatfield 106 Park Drive • Florida • North Doornfontein • Pretoria CBD St. George’s Park • Forest Hill • Orange Grove • Pretoria North CBD Port Elizabeth, 6000 • Germiston • Primrose • Pretoria West +27 (41) 582 1450 • Highlands • Randburg CBD • Silverton CBD • Highlands North • Roodepoort • Sunnyside WESTERN CAPE KWAZULU NATAL 5th Floor South Block, Upper East Side 31 Brickfield Road DURBAN • Montclair • Wentworth Woodstock, • Albert Park • Overport Cape Town, 7925 • Bluff • Pinetown Central PIETERMARITZBURG +27 -

Exploring High Streets in Suburban Johannesburg

EXPLORING HIGH STREETS IN SUBURBAN JOHANNESBURG By Tatum Tahnee Kok A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Town and Regional Planning. Johannesburg, 2016 1 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. It is being submitted for the Degree of Master of Science to the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination to any other University. …………………………………………………………………………… (Signature of Candidate) ……….. Day of …………….., …………… (Day) (Month) (Year) 2 ABSTRACT Traditionally the high street serviced residents in the local suburb. The proliferation of entertainment and leisure activities on the high street in suburban Johannesburg has appealed to people in the broader region. These social spaces within the suburb provide a simultaneous interaction of individuals who can carry out their daily activities of shopping, dining and socializing and essentially has contributed to these high streets being successful destination points. Patrons, the foot traffic of the high street, sustain businesses on the high street. Some business owners neglect to implement city by-laws and comply with licensing regulations often perpetuating unfavourable circumstances for residents in the suburb. Noise, petty crime and parking constraints detract from the street's allure. Alternatively, some residents enjoy easy access to the street's activities. Using a mixed method research approach, this research reveals some of the perceptions, regulations and tensions regarding the prominence of entertainment and leisure activities on the high street. Three case studies (7th Street in Melville, 4th Avenue in Parkhurst and Rockey/Raleigh Street in Greater Yeoville) are explored to evaluate the role of entertainment and leisure on the suburban high street.