Johannesburg Street Traders Halt Operation Clean Sweep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

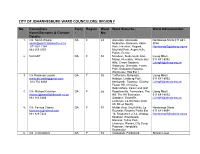

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Are Johannesburg's Peri-Central Neighbourhoods Irremediably 'Fluid'?

Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams Claire Bénit-Gbaffou To cite this version: Claire Bénit-Gbaffou. Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Lo- cal leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams. Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds), Changing Space, Changing City., Wits University Press, pp.252-268, 2014, 10.18772/22014107656.17. hal-02780496 HAL Id: hal-02780496 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02780496 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 13 Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams CLAIRE BÉNIT-gbAFFOU Johannesburg’s inner city is a convenient symbol in contemporary city culture for urban chaos, unpredictability, endless mobility and undecipherable change – as emblematised by portrayals of the infamous Hillbrow in novels and movies (Welcome to our Hillbrow, Room 207, Zoo City, Jerusalema)1 and in academic literature (Morris 1999; Simone 2004). Inner-city neighbourhoods in the CBD and on its immediate fringe (or ‘peri-central’ areas) currently operate as ports of entry into South Africa’s economic capital, for both national and international migrants. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

Public Announcement from City Power Johannesburg You Are Hereby

City Power Johannesburg 40 Heronmere Road PO Box 38766 Tel +27(0) 11 490 7000 Reuven Booysens Fax +27(0) 11 490 7590 Johannesburg 2016 www.citypower.co.za Public Announcement from City Power Johannesburg You are hereby notified of a planned power interruption on Monday the 10th of July 2017 at 22h00 and the following areas will be affected: Benrose Benrose Ext 1, 10, 11, 12, Cleveden and Cleveden 13, 14, 15, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Ext 7 8, 9 Denver Denver Ext 1, 10, 11, 12, Elcedes 13, 15, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9 Heriodtdale Ext 10,1,12, Jeppestown Jeppestown South 13, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Malvern and Malvern Ext Reynolds View Spes Bona 1, 3 Wolhuter Kensington Kensington Ext 11, 12, 13, 3, 4, 8, 9 Oospoort Ext 1 South Kensington The Gables and The Gabels Ext 1, 2, 3, 4 Bramley & Bramley Ext 1 Bramley Park Bramley View Ext 2, 8 Crystal Gardens A.H Gresswold Kew & Kew Ext 1 Lyndhurst & Lyndhurst Raumaris Park Whitney Gardens Ext 10, Ext 1, 2 14,1, 15, 2, 3, 4, 9 Wynberg Alexandra Ext 15, 18, 36, Bramley Manor 8 Bramley View Bramley View Ext 1, 11, Casey Park 12, 14, 15, 16, 2, 4, 6, 8,9 Corlett Gardens & Colett Dorelan Dunsevern & Dunsevern Gardens Ext 1, 2, 3 Ext 1, 4 Fairmount & Fairmount Formain Glenhazel & Glenhazel Ext 2 Ext 10, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9 Highlands North & Highlands North Ext 2, 3, Lombardy East & West Highlands North Ext 3, 9 4, 6, 6, 9 Longmeadow Business Percelia Estate & Raedene Estate & Estate Ext 10, 2 Percelia Estate Ext 1, 2 Raedene Estate Rembrandt Park & Rembrandt Ridge Rouxville Rembrandt Park Ext 10, 11, 12, 4, 5, 6, 9 Sunningdale -

Noordgesig Social Cluster Project Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan

tsica – the significance of cultural history Noordgesig Social Cluster Project Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan Draft for public comment Prepared for: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG Johannesburg Development Agency No 3 Helen Joseph Street The Bus Factory Newtown Johannesburg, 2000 PO Box 61877 Marshalltown 2107 Tel +27(0) 11 688 7851 Fax +27(0) 11 688 7899/63 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Ms. Shaakira Chohan Tel +27(0) 11 688 7858 E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by: tsica heritage consultants & Jacques Stoltz, Piet Snyman, Ngonidzashe Mangoro, Johann le Roux 41 5th Avenue Westdene 2092 Johannesburg tel/fax 011 477 8821 [email protected] th 25 of June 2016 Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants 2 Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Acknowledgements Tsica heritage consultants would like to thank the following community members for their assistance during the compilation of this report: Patrick Randles, George Rorke, Alan Tully, Terence Jacobs, Delia Malgas, Sister Elizabeth “Betty Glover, Bernice Charles, Rev. Stewart Basson, Nolan Borman, Councillor Basil Douglas, Burg Jacobs, Ivan Lamont, Charles Abrahams, Raymond Benson and Jeff Modise and everyone else who attended our meetings, opened their doors for us or talked to us in the streets of Bulte. Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants 3 Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Important notice The assessment of the heritage impacts of the proposed developments contemplated in this report is strictly limited to the developments detailed in the Noordgesig Precinct Plan of the City of Johannesburg (June 2016). -

Effect of Grootvlei Mine Water on the Blesbokspruit

THE EFFECT OF GROOTVLEI MINE WATER ON THE BLESBOKSPRUIT by TANJA THORIUS Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE in ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT in the Faculty of Science at the Rand Afrikaans University Supervisor: Professor JT Harmse July 2004 The Impact of Grootvlei Mine on the Water Quality of the Blesbokspruit i ABSTRACT Gold mining activities are widespread in the Witwatersrand area of South Africa. These have significant influences, both positive and negative, on the socio-economic and bio -physical environments. In the case of South Africa’s river systems and riparian zones, mining and its associated activities have negatively impacted upon these systems. The Blesbokspruit Catchment Area and Grootvlei Mines Limited (hereafter called “Grootvlei”) are located in Gauteng Province of South Africa. The chosen study area is east of the town of Springs in the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality on the East Rand of Gauteng Province. Grootvlei, which has been operating underground mining activities since 1934, is one of the last operational mines in this area. Grootvlei pumps extraneous water from its underground mine workings into the Blesbokspruit, which includes the Blesbokspruit Ramsar site. This pumping ensures that the mine workings are not flooded, which would result in the gold reserves becoming inaccessible and would shortly lead to the closure of Grootvlei. This closure would further affect at least three other marginal gold mines in the area, namely, Springs-Dagga, Droogebult-Wits and Nigel Gold Mine, all which rely on Grootvlei’s pumping to keep their workings dry. Being shallower than Grootvlei, they are currently able to operate without themselves having to pump any extraneous water from their underground workings. -

Gauteng Gauteng

Gauteng Gauteng Thousands of visitors to South Africa make Gauteng their first stop, but most don’t stay long enough to appreciate all it has in store. They’re missing out. With two vibrant cities, Johannesburg and Tshwane (Pretoria), and a hinterland stuffed with cultural treasures, there’s a great deal more to this province than Jo’burg Striking gold International Airport, says John Malathronas. “The golf course was created in 1974,” said in Pimville, Soweto, and the fact that ‘anyone’ the manager. “Eighteen holes, par 72.” could become a member of the previously black- It was a Monday afternoon and the tees only Soweto Country Club, was spoken with due were relatively quiet: fewer than a dozen people satisfaction. I looked around. Some fairways were in the heart of were swinging their clubs among the greens. overgrown and others so dried up it was difficult to “We now have 190 full-time members,” my host tell the bunkers from the greens. Still, the advent went on. “It costs 350 rand per year to join for of a fully-functioning golf course, an oasis of the first year and 250 rand per year afterwards. tranquillity in the noisy, bustling township, was, But day membership costs 60 rand only. Of indeed, an achievement of which to be proud. course, now anyone can become a member.” Thirty years after the Soweto schoolboys South Africa This last sentence hit home. I was, after all, rebelled against the apartheid regime and carved ll 40 Travel Africa Travel Africa 41 ERIC NATHAN / ALAMY NATHAN ERIC Gauteng Gauteng LERATO MADUNA / REUTERS LERATO its name into the annals of modern history, the The seeping transformation township’s predicament can be summed up by Tswaing the word I kept hearing during my time there: of Jo’burg is taking visitors by R511 Crater ‘upgraded’. -

![SIDA Gauteng 2011[2].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9301/sida-gauteng-2011-2-pdf-599301.webp)

SIDA Gauteng 2011[2].Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Letter from Ria Schoeman PhD 4 Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Helpline and Hotlines in South Africa MUNICIPALITIES 5 City of Johannesburg 29 City of Tshwane 45 Ekurhuleni 61 Metsweding 64 Sedibeng 72 West Rand 1 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ARV: Antiretroviral OVC: Orphans and Vulnerable Children PMTCT Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission STI: Sexually transmitted infection HELPLINE AND HOTLINES IN SOUTH AFRICA Abortion Helpline 080 117 785 Aid for AIDS Helpline 0860 100 646 Alcoholics Anonymous 0861 HELPAA (0861 435 722) Ambulance (Private) 082 911 Ambulance (Public) 10177 Cell phone Emergency Number 112 Child Victims of Sexual, Emotional 0800 035 553 and Physical Abuse Helpline Childline 0800 055 555 Crime Stop 0860 010 111 Department of Education Helpline 0800 202 933 Department of Health Helpline 0800 005 133 Department of Home Affairs Hotline 0800 601 190 Department of Social Development 0800 121 314 Substance Abuse Helpline Emergency Contraception Hotline 0800 246 432 Gay and Lesbian Network Helpline 0860 333 331 HIV Medicines Helpline 0800 212 506 HIV-911 Referral Centre 0860 HIV 911 (0860 448 911) Human Rights Advice Line 0860 120 120 Lifeline Southern Africa 0861 322 322 Legal Aid South Africa Advice Line 0800 204 473 loveLife Sexual Health Line 0800 121 900 (thetha junction) Marie Stopes Clinic Toll Free Number 0800 117 785 mothers2mothers 0800 668 4377 MRI Criticare Emergency Service 0800 111 990 National AIDS Helpline 0800 012 322 National HIV Health Care Workers Hotline 0800 212 506 National Youth Information -

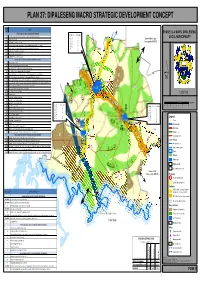

Dipaleseng Macro Strategic Development Concept

PLAN 37: DIPALESENG MACRO STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT CONCEPT Project Projects No SPATIAL OBJECTIVE: EXPLOIT ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES T 7 PHASE 3 & 4 MAPS: DIPALESENG PROJECTS: STRATEGIES: o 1 N /N 1 Compilation of an implementation plan to create mining enabling environment 17 18 C n i o g v LOCAL MUNICIPALITY 2 Beneficiation of coal 24 28 D e e Govan Mbeki Local 29 35 F l D o F Municipality (MP307) 3 (n/a) Development of a Tourism Strategy 38 43 G T 4 (n/a) Access suitable land for irrigation farming and beneficiation of agricultural products 44 46 H 47 50 I 5 (n/a) Access agricultural support programmes for the development of arable land 52 J 1! 7 (n/a) Beneficiation of agricultural products K 23! 8 (n/a) Implement land reform Programme L L 8 15 (n/a) SMME/BEE Development Programmes 4 5 SPATIAL OBJECTIVE: CREATE SUSTAINABLE HUMAN SETTLEMENTS R 17 Thusong service centres. F 18 Draft detailed Urban Design Framework for nodes E P e t r u s v d M e r w e ! 19 Upgrade of the R23 road between Greylingstad and Balfour P e t r u s v d M e r w e 1 1 5 HHaarrooffff DDaamm 20 Upgrade of the R51 road between Balfour and Grootvlei R 21! 21 Maintain R23 transport corridor to the east of Greylingstad and to the north of Balfour N 22 (n/a) Upgrade gravel access roads to schools to enable public transport provision 23 Maintain R51-R548 main road south of Grootvlei (to Vaal River) and north of Balfour (to Devon, Secunda) F 55! ´ S i y a t h e m b a 24 Develop services master plans (roads, water, sewer, electricity) for Balfour, Greylingstad and Grootvlei T S i y a t h e m b a o 28 Identification of new cemetery and land fill sites in all main towns H / ! B 1 ! e /!!! 53 L B aa ll ff o u r L 29 Upgrade Main Substations (Bulk Electricity supply) id ! u r e 53 30 (n/a) Rural Water Supply (15 boreholes) lb e 32 (n/a) Provision of VIP's rg 1:320 000 35 Develop Storm Water Master Plan N N 19! 38 Sewer Reticulation & Maintenance L B B R 39 Sewer Reticulation 700 H/H Ext. -

Department of Human Settlements Government Gazette No

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 671 NO. 671 NO. Priority Housing Development Areas Department of Human Settlements Housing Act (107/1997): Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas HousingDevelopment Priority Proposed (107/1997): Act Government Gazette No.. I, NC Mfeketo, Minister of Human Settlements herewith gives notice of the proposed Priority Housing Development Areas (PHDAs) in terms of Section 7 (3) of the Housing Development Agency Act, 2008 [No. 23 of 2008] read with section 3.2 (f-g) of the Housing Act (No 107 of 1997). 1. The PHDAs are intended to advance Human Settlements Spatial Transformation and Consolidation by ensuring that the delivery of housing is used to restructure and revitalise towns and cities, strengthen the livelihood prospects of households and overcome apartheid This gazette isalsoavailable freeonlineat spatial patterns by fostering integrated urban forms. 2. The PHDAs is underpinned by the principles of the National Development Plan (NDP) and allied objectives of the IUDF which includes: DEPARTMENT OFHUMANSETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT 2.1. Spatial justice: reversing segregated development and creation of poverty pockets in the peripheral areas, to integrate previously excluded groups, resuscitate declining areas; 2.2. Spatial Efficiency: consolidating spaces and promoting densification, efficient commuting patterns; STAATSKOERANT, 2.3. Access to Connectivity, Economic and Social Infrastructure: Intended to ensure the attainment of basic services, job opportunities, transport networks, education, recreation, health and welfare etc. to facilitate and catalyse increased investment and productivity; 2.4. Access to Adequate Accommodation: Emphasis is on provision of affordable and fiscally sustainable shelter in areas of high needs; and Departement van DepartmentNedersettings, of/Menslike Human Settlements, 2.5. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Inner City Eastern Gateway Urban Development Framework & Implementation Plan Report | 2016

INNER CITY EASTERN GATEWAY URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK & IMPLEMENTATION PLAN REPORT | 2016 Prepared for: Prepared by: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG & OSMOND LANGE ARCHITECTS JOHANNESBURG DEVELOPMENT & PLANNERS (Pty) Ltd AGENCY Unit 3, Ground Floor The Bus Factory 3 Melrose Boulevard No. 3 President Street Melrose Arch Newtown 2196 Johannesburg [t]: 011 994 4300 [t]: 011 688 7851 [f]: 011 684 1436 [f]: 011 688 7899 email: [email protected] In Collaboration with: URBAN- ECON , HATCH GOBA, U SPACE & TANYA ZACK DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8.0 URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 8.1 VISION PLAN 2.0. INTRODUCTION 8.2 LAND USE 8.2.1. PROPOSED LAND USES 3.0. STATUS QUO 8.2.2. ZONING 3.1 REGIONAL CONTEXT 8.3 PUBLIC ENVIRONMENT 3.1.1 LOCALITY 8.3.1. PUBLIC REALM 3.1.2 GAUTENG CITY REGION CONTEXT 8.3.2 MOVEMENT NETWORK 3.1.3 METROPOLITAN CONTEXT 8.3.3. PARKS & GREEN SPACES 3.1.4 THE ROLE OF JOHANNESBURG INNER CITY 8.4 BUILT FORM 3.1.5 AEROTROPOLIS CONTEXT 8.4.1. HEIGHT AND GRAIN GUIDELINES 8.4.2. STREET EDGE GUIDELINES 8.5 HOUSING 3.2 STUDY AREA 8.5.1. ASSUMPTIONS: NUMBER OF HOUSEHOLDS THAT 3.2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT REQUIRE HOUSING INTERVENTION I TOPOGRAPHY 8.5.2 ESTIMATES OF HOUSING NEED II OPEN SPACE SYSTEM 8.5.3 POSSIBLE INTERVENTIONS – HOUSING FORMS 3.2.2 BUILT ENVIRONMENT 8.5.4 APPLYING ICHIP IN EASTERN GATEWAY i LAND USE 8.5.5 LOGIC FOR HOUSING INTERVENTION II ZONING 8.5.6 ICHIP PRIORITY HOUSING PRECINCTS III BUILT FORM 8.5.7 HOUSING DELIVERY REQUIREMENTS iv HERITAGE 8.5.8 PROPOSED HOUSING INTERVENTIONS v TRANSPORT & TRAFFIC 8.5.9 PROPOSED HOUSING TYPOLOGIES 3.2.3 SOCIO- ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT 8.6 SOCIAL FACILITIES i POPULATION 8.6.1.