Johannesburg and Its Epidemics: Can We Learn from History?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

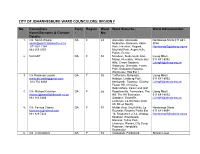

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

Discussion Have You Heard from GuiDe Johannesburg Have You Heard Campaign support from major funding provided By from JoHannesburg Have You Heard from Johannesburg The World Against Apartheid A new documentary series by two-time Academy Award® nominee Connie Field TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 about the Have you Heard from johannesburg documentary series 3 about the Have you Heard global engagement project 4 using this discussion guide 4 filmmaker’s interview 6 episode synopses Discussion Questions 6 Connecting the dots: the Have you Heard from johannesburg series 8 episode 1: road to resistance 9 episode 2: Hell of a job 10 episode 3: the new generation 11 episode 4: fair play 12 episode 5: from selma to soweto 14 episode 6: the Bottom Line 16 episode 7: free at Last Extras 17 glossary of terms 19 other resources 19 What you Can do: related organizations and Causes today 20 Acknowledgments Have You Heard from Johannesburg discussion guide 3 photos (page 2, and left and far right of this page) courtesy of archive of the anti-apartheid movement, Bodleian Library, university of oxford. Center photo on this page courtesy of Clarity films. Introduction AbouT ThE Have You Heard From JoHannesburg Documentary SEries Have You Heard from Johannesburg, a Clarity films production, is a powerful seven- part documentary series by two-time academy award® nominee Connie field that shines light on the global citizens’ movement that took on south africa’s apartheid regime. it reveals how everyday people in south africa and their allies around the globe helped challenge — and end — one of the greatest injustices the world has ever known. -

(Special Trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300

Place Name Code Hub Surch Regional A KRIEK (special trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300 BFN No AANHOU WEN, Stellenbosch 7600 SSS No ABBOTSDALE 7600 SSS No ABBOTSFORD, East London 5241 ELS No ABBOTSFORD, Johannesburg 2192 JNB No ABBOTSPOORT 0608 PTR Yes ABERDEEN (48 hrs) 6270 PLR Yes ABORETUM 3900 RCB Town Ships No ACACIA PARK 7405 CPT No ACACIAVILLE 3370 LDY Town Ships No ACKERVILLE, Witbank 1035 WIR Town Ships Yes ACORNHOEK 1 3 5 1360 NLR Town Ships Yes ACTIVIA PARK, Elandsfontein 1406 JNB No ACTONVILLE & Ext 2 - Benoni 1501 JNB No ADAMAYVIEW, Klerksdorp 2571 RAN No ADAMS MISSION 4100 DUR No ADCOCK VALE Ext/Uit, Port Elizabeth 6045 PLZ No ADCOCK VALE, Port Elizabeth 6001 PLZ No ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 DUR No ADDNEY 0712 PTR Yes ADDO 2 5 6105 PLR Yes ADELAIDE ( Daily 48 Hrs ) 5760 PLR Yes ADENDORP 6282 PLR Yes AERORAND, Middelburg (Tvl) 1050 WIR Yes AEROTON, Johannesburg 2013 JNB No AFGHANI 2 4 XXXX BTL Town Ships Yes AFGUNS ( Special Trip ) 0534 NYL Town Ships Yes AFRIKASKOP 3 9860 HAR Yes AGAVIA, Krugersdorp 1739 JNB No AGGENEYS (Special trip) 8893 UPI Town Ships Yes AGINCOURT, Nelspruit (Special Trip) 1368 NLR Yes AGISANANG 3 2760 VRR Town Ships Yes AGULHAS (2 4) 7287 OVB Town Ships Yes AHRENS 3507 DBR No AIRDLIN, Sunninghill 2157 JNB No AIRFIELD, Benoni 1501 JNB No AIRFORCE BASE MAKHADO (special trip) 0955 PTR Yes AIRLIE, Constantia Cape Town 7945 CPT No AIRPORT INDUSTRIA, Cape Town 7525 CPT No AKASIA, Potgietersrus 0600 PTR Yes AKASIA, Pretoria 0182 JNB No AKASIAPARK Boxes 7415 CPT No AKASIAPARK, Goodwood 7460 CPT No AKASIAPARKKAMP, -

Zapiro : Tooning the Odds

12 Zapiro : Tooning The Odds Jonathan Shapiro, or Zapiro, is the editorial cartoonist for The Sowetan, the Mail & Guardian and the Sunday Times, and his work is a richly inventive daily commentary on the rocky evolution of South African democracy. Zapiro’s platforms in the the country’s two largest mass-market English-language newspapers, along with one of the most influential weeklies, give him influential access to a large share of the national reading public. He occupies this potent cultural stage with a dual voice: one that combines a persistent satirical assault on the seats of national and global power with an unambiguous commitment to the fundamentally optimistic “nation-building” narrative within South African political culture. Jeremy Cronin asserts that Zapiro "is developing a national lexicon, a visual, verbal and moral vocabulary that enables us to talk to each other, about each other."2 It might also be said that the lexicon he develops allows him to write a persistent dialogue between two intersecting tones within his own journalistic voice; that his cartoons collectively dramatise the tension between national cohesion and tangible progress on the one hand, and on the other hand the recurring danger of damage to the mutable and vulnerable social contract that underpins South African democracy. This chapter will outline Zapiro’s political and creative development, before identifying his major formal devices and discussing his treatment of some persistent themes in cartoons produced over the last two years. Lines of attack: Zapiro’s early work Zapiro’s current political outlook germinated during the State of Emergency years in the mid- eighties: he returned from military service with a fervent opposition to the apartheid state, became an organiser for the End Conscription Campaign, and turned his pen to struggle pamphlets. -

Noordgesig Social Cluster Project Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan

tsica – the significance of cultural history Noordgesig Social Cluster Project Heritage Impact Assessment & Conservation Management Plan Draft for public comment Prepared for: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG Johannesburg Development Agency No 3 Helen Joseph Street The Bus Factory Newtown Johannesburg, 2000 PO Box 61877 Marshalltown 2107 Tel +27(0) 11 688 7851 Fax +27(0) 11 688 7899/63 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Ms. Shaakira Chohan Tel +27(0) 11 688 7858 E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by: tsica heritage consultants & Jacques Stoltz, Piet Snyman, Ngonidzashe Mangoro, Johann le Roux 41 5th Avenue Westdene 2092 Johannesburg tel/fax 011 477 8821 [email protected] th 25 of June 2016 Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants 2 Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Acknowledgements Tsica heritage consultants would like to thank the following community members for their assistance during the compilation of this report: Patrick Randles, George Rorke, Alan Tully, Terence Jacobs, Delia Malgas, Sister Elizabeth “Betty Glover, Bernice Charles, Rev. Stewart Basson, Nolan Borman, Councillor Basil Douglas, Burg Jacobs, Ivan Lamont, Charles Abrahams, Raymond Benson and Jeff Modise and everyone else who attended our meetings, opened their doors for us or talked to us in the streets of Bulte. Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants 3 Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] Important notice The assessment of the heritage impacts of the proposed developments contemplated in this report is strictly limited to the developments detailed in the Noordgesig Precinct Plan of the City of Johannesburg (June 2016). -

Braamfontein Aims to Be National Digital Hub

Views, Comments and Opinion Braamfontein aims to be national digital hub by Hans van de Groenendaal, features editor Prof. Barry Dwolatzky, director of the the Joburg Centre for Sofware Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand believes in the value of an attractive and vibrant digital technolgy hub in Braamfontein to support skills development, job creation, entrepreneurship and the rejuvenation of Johanesburg's inner city. Braamfontein has seen much urban renewal in recent times, and is begining to regain its erstwhile trendiness. Prof. Barry Dwolatzky calls this new digital development the Tshimologong Precinct and is planning to create an exciting new-age software skills and innovation hub. Tshimologong is the seSotho for "place of new beginnings". The precinct is part of an ambitious ICT cluster development programme, Tech-in-Braam, aimed at turning the once dilapidated suburb into the new technical heart of South Africa and beyond. Prof. Dwolatzky is in the process of setting up shop in a series of five unused buildings. After some extensive refurbishments, a one-time night club floor will become a meeting space and will house server rooms; warehouses will be converted into computer labs and retail outlets will reincarnate as development pods. Braamfontein’s many advantages have made the neighbourhood an obvious The Tshimologong precinct will be developed in this part of Braamfontein. location for the precinct – it is convenient to two universities (the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg); it is centrally located with good public transport; it is the site of local government departments and many non-governmental organisations; and it is within easy reach of banks and mining houses, as well as a multitude of corporate headquarters. -

Blurred Lines

BLURRED LINES: HOW SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM HAS CHANGED WITH A NEW DEMOCRACY AND EVOLVING COMMUNICATION TOOLS Zoe Schaver The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism Advised by: __________________________ Chris Roush __________________________ Paul O’Connor __________________________ Jock Lauterer BLURRED LINES 1 ABSTRACT South Africa’s developing democracy, along with globalization and advances in technology, have created a confusing and chaotic environment for the country’s journalists. This research paper provides an overview of the history of the South African press, particularly the “alternative” press, since the early 1900s until 1994, when democracy came to South Africa. Through an in-depth analysis of the African National Congress’s relationship with the press, the commercialization of the press and new developments in technology and news accessibility over the past two decades, the paper goes on to argue that while journalists have been distracted by heated debates within the media and the government about press freedom, and while South African media companies have aggressively cut costs and focused on urban areas, the South African press has lost touch with ordinary South Africans — especially historically disadvantaged South Africans, who are still struggling and who most need representation in news coverage. BLURRED LINES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction A. Background and Purpose B. Research Questions and Methodology C. Definitions Chapter II: Review of Literature A. History of the Alternative Press in South Africa B. Censorship of the Alternative Press under Apartheid Chapter III: Media-State Relations Post-1994 Chapter IV: Profits, the Press, and the Public Chapter V: Discussion and Conclusion BLURRED LINES 3 CHAPTER I: Introduction A. -

The Politics of the Coronavirus and Its Impact on International Relations

Vol. 14(3), pp. 116-125, July-September 2020 DOI: 10.5897/AJPSIR2020.1271 Article Number: FA1630564661 ISSN: 1996-0832 Copyright ©2020 African Journal of Political Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR International Relations Full Length Research Paper The politics of the coronavirus and its impact on international relations Bheki Richard Mngomezulu Department of Political Science, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. Received 7 June, 2020; Accepted 1 July, 2020 Pandemic outbreaks are not a new phenomenon globally. There is plethora of evidence to substantiate this view. However, each epidemic has its own defining features, magnitude, and discernible impact. Societies are affected differently. The coronavirus or COVID-19 is not an incongruity. Although it is still active, thus making detailed empirical data inconclusive, it has already impacted societies in many ways - leaving indelible marks. Regarding methodology, this paper is an analytic and exploratory desktop study which draws evidence from different countries to advance certain arguments. It is mainly grounded in political science (specifically international relations) and history academic disciplines. Firstly, the paper begins by looking at how the coronavirus has affected international relations – both positively and negatively. Secondly, using examples from different countries, it argues that the virus has exposed the political leadership by bringing to bear endemic socio-economic inequalities which result in citizens responding differently to government regulations meant to flatten the curve of infection. Thirdly, in the context of Africa, the paper makes a compelling argument that some of the socio-economic situations found within the continent are remnants of colonialism and apartheid. -

Speech by Cllr Mpho Parks Tau, Executive Mayor Of

SPEECH BY CLLR MPHO PARKS TAU, EXECUTIVE MAYOR OF JOHANNESBURG, AT THE GENERAL MEETING OF MEMBERS OF THE GAUTENG CIRCLE OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF THE NOTHERN PROVINCES, SUNNYSIDE PARK HOTEL, JOHANNESBURG, 11 OCTOBER, 2014 Chairperson of the Gauteng Circle of the Law Society Mr. T. Mkhonto Our keynote speaker for today Honourable Judge V Saldanha Members of the Gauteng Circle of the Law Society Distinguished guests Ladies and Gentlemen Good Morning On behalf of the City of Johannesburg I would like to thank you for inviting us to this important function of the legal fraternity. Gatherings like these offer us an opportunity to share ideas but also to immerse ourselves in the country’s legal issues and in the latest debates in the field. Ladies and gentlemen, as a country we have come a long way since the dawn of democracy in 1994. The democratically elected government led by the African National Congress has done much to deliver on the people’s expectations since then. We now have the most liberal constitution in the world. Previously, human rights violations were an intrinsic part of the system. Now, when they occur, they are seen as a disgrace to our society and action is taken against the perpetrators. Apartheid, which left many of us with physical and mental scars, has been buried for good. As the City of Johannesburg we have also made strides in implementing national policy. We continue to transform our City, including our townships such as Soweto and Alexandra, from a city based on segregation and suspicion to a non-racial people’s city. -

Statement of the Executive Mayor of Johannesburg, Cllr. Geoffery Makhubo, on COVID-19 Interventions

Statement of the Executive Mayor of Johannesburg, Cllr. Geoffery Makhubo, on COVID-19 Interventions 18 March 2020 The Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg, Cllr Geoffrey Makhubo, yesterday, 17 March 2020, convened an urgent Mayoral Committee meeting as a response to the pronouncements of President Cyril Ramaphosa around the management and spread of the COVID-19. In the recently released figures by the Department of Health, we have noted that the majority of cases reported and confirmed are within the Gauteng province and the City of Johannesburg in particular. Given that the City has a population of 5, 5 million residents, mostly located in high density settlements and with a significant population located in informal settlements, this warrants the implementation of drastic yet responsible interventions to prevent a potential rapid spread that could affect millions in a short space of time and with devastating effects on the capacity of our health facilities and personnel to respond. 1 As a City we are organized into seven (7) regions which also cover key nodal points such as the Johannesburg inner-city, Ennerdale, Fourways, Lenasia, Midrand, Randburg, Roodepoort, Sandton and Soweto. These are areas wherein there is a high concentration of people, businesses and settlements. The City’s approach is thus to prevent, contain and manage the spread of the COVID-19 through efficient and equitable deployment of resources to regions and the most vulnerable areas, particularly areas of high volumes in human traffic and informal and densely populated settlements. The Mayoral Committee in line with the above background has thus taken the following decisions: 1. -

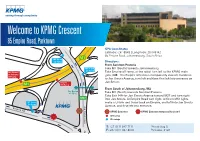

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

City of Johannesburg Pikitup

City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za DEPOT SUBURB/TOWNSHIP PRIORITY AREAS TO BE CLEARED ON FRIDAY, 05 FEB 2016 AVALON DEPOT Eldorado Park Ext 2 and Eldorado Park Proper (Michael Titus 083 260 1776) Eldorado Park Ext 10 and Proper Eldorado Park Ext 1, 3, and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 6 and 4 Eldorado Park Ext 4, Proper and Nancefield Industria Eldorado Park Ext 2, 3 and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 4 and Proper Eldorado Park Proper and M/Park Orange Farm Ext 3 and 1 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Proper CENTRAL CAMP Selinah Pimville Zones 1 - 4 Tshablala 071 8506396 MARLBORO DEPOT Buccleuch ‘Nyane Motaung - 071 850 6395 Sandown City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za MIDRAND DEPOT Cresent wood, Erands gardens, Erands AH and Noordwyk South Jeffrey Mahlangu 082 492 8893 Juskeyview, Waterval estate, South , west and north NORWOOD DEPOT Bruma (Neil Observatory Macherson 071 Kensington 682 1450) Yeoville RANDBURG DEPOT Majoro Letsela Blairgowrie 082 855 9348 ROODEPOORT DEPOT Stella Wilson - Florida 071 856 6822 SELBY DEPOT Fordsburg Sobantwana Mkhuseli CBD 1: (Noord to Commissioner & End to Rissik Streets) 082 855 9321 CBD 2: (Rissik to