Metcalf, Franz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005 Primary Point Primary Point 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 • Fax 401/658-1188 www.kwanumzen.org • [email protected] online archives www.kwanumzen.org/primarypoint Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit religious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He gave transmission to Zen Masters, and “inka”—teaching authority—to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, “dharma masters.” The Kwan Um School of Zen supports the worldwide teaching schedule of the Zen Masters and Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, assists the member Zen centers and groups in their growth, issues publications In this issue on contemporary Zen practice, and supports dialogue among religions. If you would like to become a member of the School and receive Let’s Spread the Dharma Together Primary Point, see page 29. The circulation is 5000 copies. Seong Dam Sunim ............................................................3 The views expressed in Primary Point are not necessarily those of this journal or the Kwan Um School of Zen. Transmission Ceremony for Zen Master Bon Yo ..............5 © 2005 Kwan Um School of Zen Founding Teacher In Memory of Zen Master Seung Sahn Zen Master Seung Sahn No Birthday, No Deathday. Beep. Beep. School Zen Master Zen -

American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter

CHAPTER FO U R American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter ★ he Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated for weeks on end in Los Angeles. TMore than three hundred Buddhist temples sit in this great city fac- ing the Pacific, and every weekend for most of the month of May the Buddha’s Birthday is observed somewhere, by some group—the Viet- namese at a community college in Orange County, the Japanese at their temples in central Los Angeles, the pan-Buddhist Sangha Council at a Korean temple in downtown L.A. My introduction to the Buddha’s Birthday observance was at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, just east of Los Angeles. It is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere, built by Chinese Buddhists hailing originally from Taiwan and advocating a progressive Humanistic Buddhism dedicated to the pos- itive transformation of the world. In an upscale Los Angeles suburb with its malls, doughnut shops, and gas stations, I was about to pull over and ask for directions when the road curved up a hill, and suddenly there it was— an opulent red and gold cluster of sloping tile rooftops like a radiant vision from another world, completely dominating the vista. The ornamental gateway read “International Buddhist Progress Society,” the name under which the temple is incorporated, and I gazed up in amazement. This was in 1991, and I had never seen anything like it in America. The entrance took me first into the Bodhisattva Hall of gilded images and rich lacquerwork, where five of the great bodhisattvas of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition receive the prayers of the faithful. -

Great Teacher Mahapajapati Gotami

Zen Women A primer for the chant of women ancestors used at the Compiled by Grace Schireson, Colleen Busch, Gary Artim, Renshin Bunce, Sherry Smith-Williams, Alexandra Frappier Berkeley Zen Center and Laurie Senauke, Autumn 2006 A note on Romanization of Chinese Names: We used Pinyin Compiled Fall 2006 for the main titles, and also included Wade-Giles or other spellings in parentheses if they had been used in source or other documents. Great Teacher Mahapajapati Gotami Great Teacher Khema (ma-ha-pa-JA-pa-tee go-TA-me) (KAY-ma) 500 BCE, India 500 BCE, India Pajapati (“maha” means “great”) was known as Khema was a beautiful consort of King Bimbisāra, Gotami before the Buddha’s enlightenment; she was his who awakened to the totality of the Buddha’s teaching after aunt and stepmother. After her sister died, she raised both hearing it only once, as a lay woman. Thereafter, she left Shakyamuni and her own son, Nanda. After the Buddha’s the king, became a nun, and converted many women. She enlightenment, the death of her husband and the loss of her became Pajapati’s assistant and helped run the first son and grandson to the Buddha’s monastic order, she community of nuns. She was called the wisest among all became the leader of five hundred women who had been women. Khema’s exchange with King Prasenajit is widowed by either war or the Buddha’s conversions. She documented in the Abyakatasamyutta. begged for their right to become monastics as well. When Source: Therigata; The First Buddhist Women by Susan they were turned down, they ordained themselves. -

Eminent Nuns

Bu d d h i s m /Ch i n e s e l i t e r a t u r e (Continued from front flap) g r a n t collections of “discourse records” (yulu) Of related interest The seventeenth century is generally of seven officially designated female acknowledged as one of the most Chan masters in a seventeenth-century politically tumultuous but culturally printing of the Chinese Buddhist Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face creative periods of late imperial Canon rarely used in English-language sC r i p t u r e , ri t u a l , a n d iC o n o g r a p h i C ex C h a n g e in me d i e v a l Ch i n a Chinese history. Scholars have noted scholarship. The collections contain Christine Mollier the profound effect on, and literary records of religious sermons and 2008, 256 pages, illus. responses to, the fall of the Ming on exchanges, letters, prose pieces, and Cloth ISBN: 978-0-8248-3169-1 the male literati elite. Also of great poems, as well as biographical and interest is the remarkable emergence autobiographical accounts of various “This book exemplifies the best sort of work being done on Chinese beginning in the late Ming of educated kinds. Supplemental sources by Chan religions today. Christine Mollier expertly draws not only on published women as readers and, more im- monks and male literati from the same canonical sources but also on manuscript and visual material, as well portantly, writers. -

Dharma Combat Zen Master Wu Kwang Zen Master Wu Bong (Richard Shrobe)

Dharma Combat Zen Master Wu Kwang Zen Master Wu Bong (Richard Shrobe) (Jacob Perl) Question: You now become Buddha but, Zen Master Seung Sahn says, "In the end of the world, not so many Question: The Heart Sutra says form is emptiness, people believe Buddha's speech." So, if nobody listens emptiness is form. Then why do you practice so hard, to you, what can you do? Providence Zen Center style? Zen Master Wu Kwang: You already understand. Zen Master Wu Bong: For you. Q: So I ask you. Q: I don't understand. ZMWK: Soon, lunch is coming. Don't worry... Your ZMWB:Not enough? stomach is already full? Q: So please teach me. Q: I'm not asking about stomach... ZMWB: Go drink some tea. ZMWK: Not enough? Q: Thank you for your teaching. Q: Not enough. ZMWB: You're welcome. ZMWK: Did you get enough sleep last night? Q: Yes, thank you. Thank you for your teaching. Q: Our teachers said that all Buddhas are the true masters in front of your nose. So already all true masters Q: So, our teaching appears to be to take away this appeared without any ceremony. What are you doing up opposites world and attain this don't know world. So there? what is taking away this opposites world and attaining ZMWB: You already understand. don't know world? Q: I ask you. ZMWK: You already understand. ZMWB: Sitting here talking with you. Q: I'm asking you. Q: Thank you very much. ZMWK: Your face is brown. My face is red. -

P Int Primary Volume 33 • Number 1 • Spring 2016

PRIMARY POINT® Kwan Um School of Zen 99 Pound Rd Cumberland, RI 02864-2726 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Primary Primary P int P Volume 33 • Number 1 • Spring 2016 2016 Spring • 1 Number • 33 Volume Summer Kyol Che 2016 July 9 - August 5 Silent retreats including sitting, chanting, walking and bowing practice. Dharma talks and Kong An interviews. Retreats Kyol Che Visit, practice or live at the head YMJJ 401.658.1464 Temple of Americas Kwan Um One Day www.providencezen.com School of Zen. Solo Retreats [email protected] Guest Stays Residential Training Rentals PRIMARY POINT Spring 2016 Primary Point 99 Pound Road IN THIS ISSUE Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 The Moment I Became a Monk www.kwanumzen.org Zen Master Dae Jin .....................................................................4 online archives: Visit kwanumzen.org to learn more, peruse back Biography of Zen Master Dae Jin ............................................5 issues and connect with our sangha. Funeral Ceremony and Cremation Rites for Zen Master Dae Jin ...................................................................5 Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit reli- gious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Bodhisattva Way Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Zen Master Dae Jin .....................................................................6 Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um The True Spirit of Zen sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He Zen Master Dae Jin gave transmission to Zen Masters, and inka (teaching author- .....................................................................8 ity) to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sas (dharma masters). -

The Compass of Zen by Zen Master Seung Sahn

I N D E X to The Compass of Zen by Zen Master Seung Sahn John Holland Ty Koontz The Kwan Um School of Zen 2016 Foreword Zen Master Seung Sahn tells many good stories in his book, including how he shocked a group of French priests in explaining primary point to them and how nuns from the Eastern temple and the Western temple vied to impress Zen Master Hak Un with their pronunciations of Kwan Seum Bosal. When I prepare a dharma talk, the question for me has always been, where in The Compass of Zen are the stories discussed? The work desperately needed an index. Experience told me it would be a difficult task, and I turned for help to Ty Koontz. I had admired the index Ty made for Zen Master Wu Kwang’s (Richard Shrobe) book Elegant Failure: A Guide to Zen Koans and was delighted that Ty agreed to help me. Because we have attempted to do justice to DSSN’s teaching, for which we are all so grateful, this index is long. The ideal index does not exist. All an indexer can do is to make the best possible index he or she can. That means following one’s intuition and general knowledge. One of the most challenging aspects of making an index for The Compass of Zen is the way in which everything is interrelated. Cross-references are needed to help the reader find related concepts while avoiding an enormous snarled spider-web of relationships. Main headings for concepts like attainment, emptiness, meditation, mind, practice, suffering, thinking, and truth are necessary, but these concepts relate to so much of the book that subentries could easily overwhelm the index. -

The New Buddhism: the Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition

The New Buddhism: The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS the new buddhism This page intentionally left blank the new buddhism The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman 1 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and an associated company in Berlin Copyright © 2001 by James William Coleman First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, 10016 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2002 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coleman, James William 1947– The new Buddhism : the western transformation of an ancient tradition / James William Coleman. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-19-513162-2 (Cloth) ISBN 0-19-515241-7 (Pbk.) 1. Buddhism—United States—History—20th century. 2. Religious life—Buddhism. 3. Monastic and religious life (Buddhism)—United States. I.Title. BQ734.C65 2000 294.3'0973—dc21 00-024981 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America Contents one What -

Formation and Supervision in Buddhist Chaplaincy

Formation and Supervision in Buddhist Chaplaincy Tina Jitsujo Gauthier hen a Zen student receives the Bodhisattva precepts, they take refuge in the three jewels of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Tak- Wing refuge in the Buddha is taking refuge in the formless awak- ened nature of all beings. Taking refuge in the Dharma is taking refuge in differences, the multitude of diverse forms. Taking refuge in the Sangha is taking refuge in harmony, the integration of formlessness and forms, the interdependence of all creation. Receiving the Buddhist precepts is vowing to both maintain and embody them.1 To symbolize this vow, Zen students make a rakusu2 before the precept ceremony and a kesa3 before the ordination ceremony. Both rakusu and kesa represent the field of interconnection. They are made by sewing many pieces of fabric together. I wear my kesa over my ordination robe and my rakusu over my everyday clothing. There is a ritual for putting on the kesa and rakusu, along with a verse: Vast is the robe of liberation a formless field of benefaction I wear the Tathagata teaching serving all sentient beings. Tina Jitsujo Gauthier completed her CPE resident training in New York City and later served as a chaplain in San Diego. She has a PhD in religious studies from the University of the West and was ordained as a Zen Buddhist priest in 2010. She currently serves on the faculty in the Buddhist Chaplaincy Program, University of the West, Rosemead, Cali- fornia. Email: [email protected]. Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry ISSN 2325-2847 (print)* ISSN 2325-2855 (online) * © Copyright 2017 Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry All Rights Reserved 186 FORMatiON AND SUPERVISION IN BUDDHIST CHAPLAINCY Tathagata is the Enlightened Buddha and also means thusness.4 Remem- bering that I am wearing thusness is a way of seeing interconnection in my life as a gift. -

Volume 27 • Number 1 • Winter 2010

Volume 27 • Number 1 • Winter 2010 Primary P int Primary Point 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 www.kwanumzen.org [email protected] online archives: www.kwanumzen.org/primarypoint Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit For All of Us religious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He gave transmission to Zen Masters, and “inka”—teaching authority—to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, IN THIS ISSUE “dharma masters.” For All of Us The Kwan Um School of Zen supports the worldwide teaching schedule of the Zen Masters and Ji Do Poep Zen Master Dae Bong ........................................................3 Sa Nims, assists the member Zen centers and groups Transmission Ceremony for Zen Master Dae Jin .............4 in their growth, issues publications on contemporary Zen practice, and supports dialogue among religions. Inka Ceremony for Paul Majchrzyk JDPSN ....................6 If you would like to become a member of the School Inka Ceremony for José Ramirez JDPSN ........................8 and receive Primary Point, see page 25. The circulation 2] is 5000 copies. The Whole World is a Single Flower Conference The views expressed in Primary Point are not necessarily those of this journal or the Kwan Um School of Zen. Opening Poem -

Buddhism and Ecology Bibliography

The Forum on Religion and Ecology Buddhism and Ecology Bibliography Bibliography by Chris Ives, Stonehill College, Duncan Ryuken Williams, Trinity College, and The Forum on Religion and Ecology Abe, Masao. “Man and Nature in Christianity and Buddhism.” Japanese Religions 7, no. 1 (July 1971): 1–10. Abraham, Ralph. “Orphism: The Ancient Roots of Green Buddhism.” In DharmaGaia: A Harvest of Essays in Buddhism and Ecology, ed. Allan Hunt Badiner, 39–49. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax Press, 1990. Aitken, Robert. “Envisioning the Future.” In Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism, edited by Stephanie Kaza and Kenneth Kraft, 423-38. Boston: Shambhala, 2000. _____. The Practice of Perfection: The Paramitas from a Zen Buddhist Perspective. New York: Pantheon, 1994. _____. “Right Livelihood for the Western Buddhist.” In Dharma Gaia: A Harvest of Essays in Buddhism and Ecology, ed. Allan Hunt Badiner, 227–32. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax Press, 1990. Reprinted in Primary Point 7, no. 2 (summer 1990): 19–22. _____. “Gandhi, Dogen, and Deep Ecology.” In Deep Ecology: Living As If Nature Mattered, eds. Bill Devall and George Sessions, 232–35. Salt Lake City, Utah: Peregrine Smith Books, 1985. Reprinted in The Path of Compassion: Writings on Socially Engaged Buddhism, ed. Fred Eppsteiner, 86–92. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax Press, 1988. _____. The Mind of Clover: Essays in Zen Buddhist Ethics. San Francisco, Calif.: North Point Press, 1984. Allendorf, Fred W., and Bruce A. Byers. “Salmon in the Net of Indra: A Buddhist View of Nature and Communities.” Worldviews 2 (1998): 37-52. Almon, Bert. “Buddhism and Energy in the Recent Poetry of Gary Snyder.” Mosaic 11 (1977): 117–25. -

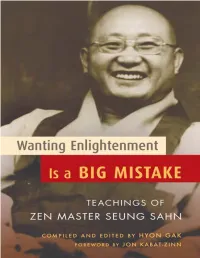

Wanting Enlightenment Is a Big Mistake

“Now that Soen Sa Nim [Zen Master Seung Sahn] is gone, we have only the stories, and, thankfully, books such as this one, to help bring him alive to those who never had a chance to encounter him in the flesh. In these pages, if you linger in them long enough, and let them soak into you, you will indeed meet him in his inimitable suchness, and perhaps much more important, as would have been his hope, you will meet yourself.” —Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of Coming to Our Senses “Zen Master Seung Sahn’s teachings will always bring great light into the world. His extraordinary wit, intelligence, courage, and compassion are brought to us in this wonderful and important book. Thousands of students have benefited from his great understanding. Now more will come to know the heart of this rare and profound human being.” —Joan Halifax, Abbot, Upaya Zen Center ABOUT THE BOOK A major figure in the transmission of Zen to the West, Zen Master Seung Sahn was known for his powerful teaching style, which was direct, surprising, and often humorous. He taught that Zen is not about achieving a goal, but about acting spontaneously from “don’t-know mind.” It is from this “before- thinking” nature, he taught, that true compassion and the desire to serve others naturally arises. This collection of teaching stories, talks, and spontaneous dialogues with students offers readers a fresh and immediate encounter with one of the great Zen masters of the twentieth century. HYON GAK SUNIM, a Zen monk, was born Paul Muenzen in Rahway, New Jersey.