Planning in Cold War Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aporie Dell'integrazione Europea: Tra Universalismo Umanitario E

TRA UNIVERSALISMO UMANITARIO E SOVRANISMO APORIE DELL’INTEGRAZIONE EUROPEA: Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Scuola delle Scienze Umane e Sociali Scuola delle Scienze Umane e Sociali Quaderni 19 Questo volume è frutto di un percorso di studio e di ricerca che ha coinvolto studiosi afferenti all’Università di Évora e al Centro de Investigação em Ciência Política (CICP) in Portogallo e studiosi del DSU della Federico II di Napoli e di altre prestigiose universi- APORIE DELL’INTEGRAZIONE EUROPEA: tà italiane. Articolato in tre sezioni, affronta con un approccio in- terdisciplinare la tensione tra l’universalismo – inteso tanto come TRA UNIVERSALISMO UMANITARIO principio filosofico proprio della tradizione culturale occidentale, E SOVRANISMO quanto come principio giuridico-politico che è alla base del proces- so di integrazione – e il principio di sovranità che invece tende a a cura di Anna Pia Ruoppo e Irene Viparelli preservare l’autonomia politica degli stati all’interno del processo di integrazione. Contributi di: Peluso, Morfino, Cacciatore, Gianni- ni, Rocha Cunha, Boemio, Basso, Amendola, Arienzo, Tinè, Höbel, Donato, D’Acunto. Anna Pia Ruoppo è ricercatrice di Filosofia Morale presso il Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell’Università di Napoli “Federico II” e insegna Filosofia Pra- tica nel CdlM in Filosofia. La sua ricerca si articola intorno al nesso tra etica, prassi ed esistenza, umanismo e antiumanismo con particolare riferimento al pensiero di Heidegger e Sartre. È autrice di numerosi saggi e traduzioni, oltre che dei libri: Vita e Metodo (Firenze 2008), L’attimo della decisione. Su possibi- lità e limiti di un’etica in Essere e Tempo (Genova 2011). -

Fonds André Fougeron Inventaire

Fonds André Fougeron (1913-1998) Inventaire Versement de 2001 201FGR/1 - 201FGR/29 Instrument de rechercheréalisé par Anysia l’Hôtellier sous la direction de Sandrine Samson octobre 2012 révisé en janvier 2019 © Imec - Tous droits réservés Introduction Identification Producteur : André Fougeron Bbiographie : Autodidacte issu d’un milieu ouvrier, André Fougeron entra en peinture dans les années 1935-1936 et adhéra au Parti communiste français en 1939. Tout en continuant à exposer pendant l’Occupation, il transforma son atelier en imprimerie clandestine et fonda le Front national des arts avec Édouard Goerg et Édouard Pignon. À la Libération, attaché au cabinet de Joseph Billiet, directeur des Beaux-Arts, il fut chargé d’organiser l’épuration de la scène artistique française et de préparer un hommage à Picasso au Salon d’automne de 1944. Élu secrétaire général de l’Union des arts plastiques, il obtint le prix national des Arts et des Lettres (1946). À partir de 1947-1948, s’éloignant d’une certaine tradition moderne proche de Picasso et du fauvisme, Fougeron devint le chef de file du Nouveau Réalisme, trop facilement perçu comme la version française du réalisme socialiste. Sa toile Parisiennes au marché, véritable manifeste pictural, fit scandale au Salon d’automne de 1948. Fidèle à ses convictions communistes, André Fougeron n’a cessé de questionner son époque à travers une œuvre souvent teintée d’allégorie. Durant les années soixante-dix, il fut considéré comme un précurseur de la Nouvelle Figuration critique. Modalité d'entrée Fonds déposé par les ayants droit en 2001. Contenu et structure Présentation du contenu : Une importante correspondance (avec notamment Renato Guttuso, Jean Guillon, Peintres témoins de leur temps, Union des artistes de l'URSS...) et de nombreux dossiers thématiques éclairent tout à la fois l'évolution artistique et les activités militantes au sein du Parti communiste français d'André Fougeron. -

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

World Migration Report 2005

WORLD MIGRATION Costs and benefits of international migration 2005 VOLUME 3 – IOM World Migration Report Series 2005 WORLD MIGRATION The opinions and analyses expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect the views and official policies of the International Organization for Migration or its Member States. The book is an independent publication commissioned by IOM. It is the fruit of a collaborative effort by a team of contributing authors and the editorial team under the direction of the editor-in-chief. Unless otherwise stated, the book does not refer to events occurring after November 2004. The maps do not reflect any opinion on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or the delimitation of frontiers or boundaries. Publisher International Organization for Migration 17, route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax.: +41 22 798 61 50 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.iom.int ISSN 1561-5502 ISBN 92-9068-209-4 Layout/production: Explorations – 74 Chamonix France – +33 (0)4 50 53 71 45 Printed in France by Clerc S.A.S– 18200 Saint-Amand Montrond © Copyright International Organization for Migration, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 4 WORLD MIGRATION 2005 IOM EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-In-Chief And Concept Irena Omelaniuk Editorial Board Gervais -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

The International Possibilities of Insurgency and Statehood in Africa: the U.P.C

The International Possibilities of Insurgency and Statehood in Africa: The U.P.C. and Cameroon, 1948-1971. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2013 Thomas Sharp School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Table of Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 5 DECLARATION ....................................................................................................................... 6 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT .................................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 9 The U.P.C.: Historical Context and Historiography ......................................................... 13 A Fundamental Function of African Statehood ................................................................. 24 Methodology and Sources: A Transnational Approach ..................................................... 32 Structure of the Thesis ....................................................................................................... 37 CHAPTER ONE: METROPOLITAN -

From the Collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ

From the collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ These documents can only be used for educational and research purposes (“Fair use”) as per U.S. Copyright law (text below). By accessing this file, all users agree that their use falls within fair use as defined by the copyright law. They further agree to request permission of the Princeton University Library (and pay any fees, if applicable) if they plan to publish, broadcast, or otherwise disseminate this material. This includes all forms of electronic distribution. Inquiries about this material can be directed to: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library 65 Olden Street Princeton, NJ 08540 609-258-6345 609-258-3385 (fax) [email protected] U.S. Copyright law test The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or other reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or other reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Princeton Mathematics Community in the 1930s Transcript Number 11 (PMC11) © The Trustees of Princeton University, 1985 MERRILL FLOOD (with ALBERT TUCKER) This is an interview of Merrill Flood in San Francisco on 14 May 1984. The interviewer is Albert Tucker. -

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 Email: [email protected]

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 email: [email protected] In this column we review the following books. 1. We review four collections of papers by Donald Knuth. There is a large variety of types of papers in all four collections: long, short, published, unpublished, “serious” and “fun”, though the last two categories overlap quite a bit. The titles are self explanatory. (a) Selected Papers on Discrete Mathematics by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon. (b) Selected Papers on Design of Algorithms by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon (c) Selected Papers on Fun & Games by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. (d) Companion to the Papers of Donald Knuth by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. 2. We review jointly four books from the Bolyai Society of Math Studies. The books in this series are usually collections of article in combinatorics that arise from a conference or workshop. This is the case for the four we review. The articles here vary tremendously in terms of length and if they include proofs. Most of the articles are surveys, not original work. The joint review if by William Gasarch. (a) Horizons of Combinatorics (Conference on Combinatorics Edited by Ervin Gyori,¨ Gyula Katona, Laszl´ o´ Lovasz.´ (b) Building Bridges (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday-Vol 1) Edited by Martin Grotschel¨ and Gyula Katona. (c) Fete of Combinatorics and Computer Science (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday- Vol 2) Edited by Gyula Katona, Alexander Schrijver, and Tamas.´ (d) Erdos˝ Centennial (In honor of Paul Erdos’s˝ 100th birthday) Edited by Laszl´ o´ Lovasz,´ Imre Ruzsa, Vera Sos.´ 3. -

Cross Cultural & Strategic Management

Cross Cultural & Strategic Management The traditional Chinese philosophies in inter-cultural leadership: The case of Chinese expatriate managers in the Dutch context Li Lin, Peter Ping Li, Hein Roelfsema, Article information: To cite this document: Li Lin, Peter Ping Li, Hein Roelfsema, (2018) "The traditional Chinese philosophies in inter-cultural leadership: The case of Chinese expatriate managers in the Dutch context", Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, Vol. 25 Issue: 2, pp.299-336, https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-01-2017-0001 Permanent link to this document: https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-01-2017-0001 Downloaded on: 24 January 2019, At: 00:53 (PT) References: this document contains references to 102 other documents. The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 1078 times since 2018* Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by All users group For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. -

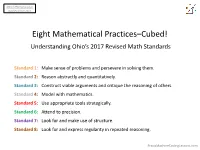

Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’S 2017 Revised Math Standards

NWO STEM Symposium Bowling Green 2017 Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards Standard 1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Standard 2: Reason abstractly and quantitatively. Standard 3: Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. Standard 4: Model with mathematics. Standard 5: Use appropriate tools strategically. Standard 6: Attend to precision. Standard 7: Look for and make use of structure. Standard 8: Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Exploring What’s New in Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards • No Revisions to Math Practice Standards. • Minor Revisions to Grade Level and/or Content Standards. • Revisions Clarify and/or Lighten Required Content. Drill-Down Some Old/New Comparisons… PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Clarify Kindergarten Counting: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Adding 5th Grade Fractions: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Solving High School Quadratics: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Ohio 2017 Math Practice Standard #1 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Mathematically proficient students start by explaining to themselves the meaning of a problem and looking for entry points to its solution. They analyze givens, constraints, relationships, and goals. They make conjectures about the form and meaning of the solution and plan a solution pathway rather than simply jumping into a solution attempt. They consider analogous problems, and try special cases and simpler forms of the original problem in order to gain insight into its solution. They monitor and evaluate their progress and change course if necessary. Older students might, depending on the context of the problem, transform algebraic expressions or change the viewing window on their graphing calculator to get the information they need. -

The Italian Communist Party and The

CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The Italian Communist Party and the Hungarian crisis of 1956 History one-year M. A. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Candidate: Aniello Verde Supervisor: Prof. Marsha Siefert Second reader: Prof. Alfred Rieber CEU eTD Collection June 4th, 2012 A. Y. 2011/2012 Budapest, Hungary Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection Acknowledgements I would like to express my frank gratitude to professors Marsha Siefert and Alfred Rieber for their indispensible support, guidance and corrections. Additionally, I would like to thank my Department staff. Particularly, I would like to thank Anikó Molnar for her continuous help and suggestions. CEU eTD Collection III ABSTRACT Despite a vast research about the impact of the Hungarian crisis of 1956 on the legacy of Communism in Italy, the controversial choices of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) have been often considered to be a sort of negative exception in the progressive path of Italian Communism toward modern European socialism. Instead, the main idea of this research is to reconstruct the PCI’s decision-making within the context of the enduring strategic patterns that shaped the political action of the party: can the communist reaction to the impact in Italy of the Hungarian uprising be interpreted as a coherent implication of the communist preexisting and persisting strategy? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to reconstruct how the news coming from Hungary left an imprint on the “permanent interests” of the PCI, and how the communist apparatus reacted to the crisis. -

Russia Hears Plan I. to Unify Germans; Already

----------------------- j^g^pipe, Steel A-Energy Might Be Used Russia Hears Plan i. FirnrSchtdules ^erP0W 6i^Pim t“T n rr^ f.FvStructures Ocean-Into Fresh-Water To Unify Germans; industry plans immL-diutc con?tnictioti i WASHINGTON, ..May 1-J (LTD — Interiiir .^ecrctary Fivil A. Seaton .-^aid lodav 'south Idaho Pipe nnd Sled corporation com- atomic energy may lie nscd to power the «ecoiul of the Koveninicnfs propo.scd dL'nmri- (\*tn rilJ13* ^ r<nnnimt'ori i\i flin fiiitil iT^^.^iianizntioii nnd announced piirchnse of th« fiiiii! .stratiowplant.s for lurninjr nea w a ter into frusli uiilcr. Sealon said the plan m a y “ oin-n Already Criticized! ! orga | p W ^ PKiimbcr o f C om m crcu industrial nrca in Soulh new horixon.s fur tlie iicaeoful ii])iilientioii <if nli-mic ^ c r t y . " He ad d ed : "T h e (iir;im n t h c Gl-'NEVA. May M (/P)—The western powers confronted Russia today with a| l* '‘^‘Tliursdny, T^ilfr5v. Lvnn L. UuiKii"ii. prc^idciil of Ihc now o f large, voltnnw o f |inv.co.-;t converted w a ter I'or'ilie arid luoas o f the w orld t^hoiild hu sweejnnjr :»)-m onih piickaBc plan for unilin^r divided Berlin, mcrj^inK' Kast and W e s t ! id president, will retain o)iura- a long .step ne;ircr reality.” A t the sam e time. .Seaton announced that n miilti-staKe Germany and inakiiiK a start on «lobul disarmament. Soviet Foreign .^linister A n d r c l l |ii't®-?”,l„^rT(rVscVt’ industries.