Nerve Advancement with End-To-End Reconstruction After Partial Neurovascular Bundle Resection:A Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Avoid the Seven Deadly Sins of Surgery

INTRODUCTION HOW TO AVOID THE ‘ SEVEN DEADLY SINS OF SURGERY ’ † † Roger Kirby * , Ben Challacombe * , Prokar Dasgupta * and Increasingly, especially as surgeons, we live ‡ † in a world where the hue and cry resulting John M. Fitzpatrick – * The Prostate Centre , and Department of Urology, MRC from one single untoward incident can Centre for Transplantation, Guy ’ s Hospital, King ’ s College London, King ’ s Health Partners, drown out the plaudits that ought to be due London, UK , and ‡ Mater Misericordiae Hospital and University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland for literally thousands of cases that have Accepted for publication 14 September 2011 gone smoothly. As a result, it is essential for each and every one of us to try by every means possible to avoid medical accidents, errors and untoward incidents. And when they do occur, we need to deal with their to the patient and his or her relatives, with A similar failure to appreciate what is really aftermath calmly and professionally. follow-up meetings, can avoid months, if happening may arise in the operating not years, of anxiety-inducing litigation. theatre. If advice from the team, including Looking back over seven decades of the assistant, the anaesthetist, the scrub combined experience in urological surgery, The increased focus on teaching these nurse and even the medical student is we thought it might be useful to consider non-technical skills aims to improve factored in, it can sometimes help to avoid a the seven key lessons (mainly learned the standards of communication [ 1 ] . The launch fatal error being made. An operation with hard way) in an attempt to help others of the BAUS national simulation program, ‘ unusual anatomy ’ often suggests that a avoid falling into the traps that lurk in wait SIMULATE, should achieve standardisation of surgeon is in the wrong tissue plane or for the unwary. -

Ilk Sayfalar 7/6/04 14:13 Page 1 ANDROLOJ‹ BÜLTEN‹

ilk sayfalar 7/6/04 14:13 Page 1 ANDROLOJ‹ BÜLTEN‹ TÜRK ANDROLOJ‹ DERNE⁄‹ YAYIN ORGANIDIR Türk Androloji Derne¤i Cemil Aslan Güder Sok. ‹dil Ap. B Blok D.1 80280 Gayrettepe, ‹stanbul Tel: 0212 288 50 99 Faks: 0212 288 50 98 E-posta: [email protected] Web: www.androloji.org.tr TÜRK ANDROLOJ‹ DERNE⁄‹ ADINA SAH‹B‹ Prof. Dr. Atefl Kad›o¤lu GENEL YAYIN YÖNETMEN‹ Uz. Dr. Memduh Ayd›n REDAKTÖR Uz. Dr. Ertan Sakall› YÖNET‹M KURULU Atefl Kad›o¤lu (Baflkan) Bülent Semerci (Genel Yazman) ‹rfan Orhan (Sayman) Ramazan Aflç› (Üye) M. Önder Yaman (Üye) Selahittin Çayan (Üye) Mustafa F. Usta (Üye) Nisan 2004 Say› 17 2 Ayda Bir Yay›nlan›r ilk sayfalar 7/6/04 14:14 Page 2 GENEL YAYIN YÖNETMENİ REDAKTÖR Uz. Dr. Memduh Aydın Uz. Dr. Ertan Sakallı BİLİMSEL KURUL ERKEK CİNSEL SAĞLIĞI Yaşlılık ve Cinsellik Ejakülasyo PrekoksRekonstrüktif Cerrahi ED ve Farmakoterapisi Doç. Dr. Ali Atan Prof. Dr. Ahmet Metin Prof. Dr. Erdal Apaydın Uz. Dr. Ertan Sakallı Uz. Dr. Melih Beysel Temel Araştırma Psikolojik ED Doç. Dr. Emin Özbek Yrd. Doç. Dr. Hakan Kılıçarslan Yrd. Doç. Dr. Mustafa Faruk Usta Doç. Dr. Doğan Şahin INFERTİLİTE Varikosel Endokrinoloji Doç. Dr. Selahittin Çayan Uz. Dr. Necati Gürbüz Doç. Dr. Turhan Çaşkurlu Doç. Dr. İsa Özbey Yardımla Üreme Teknikleri Genetik Prof. Dr. Kaan Aydos Doç. Dr. Barış Altay Uz. Dr. Lütfi Tunç Uz. Dr. A. Arman Özdemir Yrd. Doç. Dr. Murat Şamlı Obstrüktif İnfertilite Kadın İnfertilitesi Doç. Dr. Hamdi Özkara Doç. Dr. İrfan Orhan Prof. Dr. Cihat Ünlü Doç. Dr. Erkut Attar Pediatrik Androloji Androloji Laboratuarı Doç. -

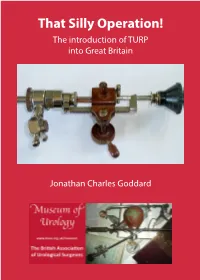

That Silly Operation! the Introduction of TURP Into Great Britain

That Silly Operation! The introduction of TURP into Great Britain Jonathan Charles Goddard 1 Jonathan Charles Goddard Curator of the Museum of Urology, BAUS Consultant Urological Surgeon Leicester General Hospital Acknowledgements I’m very grateful to Mr Bernard Ferrie FRCS, retired Urological Surgeon, who acted as expert editor. Thanks to Miss H.P.H. Goddard, Junior Curator, for photographing the instruments from the collection. I’m extremely grateful to KARL STORZ Endoscopy (UK) Ltd. who generously published this booklet for the 2019 BAUS Annual Meeting in Glasgow. 2 “That Silly Operation!” The introduction of TURP into Great Britain “We want you to give up that silly TURP operation John, it will bring St Peter’s into disrepute”. This is what John Blandy, one of the icons of Twentieth Century British Urology, was told by his “greaters and betters” at St Peter’s Hospital (the famous London urology centre) as late as the 1960’s[1]. TURP even at that stage was still seen as a “silly” new and dangerous operation that should not replace open prostatectomy. However, Transurethral Resection of the Prostate, TURP, is now seen as one of the operations that define Urology. Certain procedures, over time, have stood out as key indicators of Urology; lithotomy, lithotrity, cystoscopy, open prostatectomy, radical prostatectomy and now robotic prostatectomy. They are each surgeries of their age, their names associated with Urology and even certain urologists. A brief roll call of names are easily linked with each one; Cheselden (lithotomy), Civiale and Sir Henry Thompson (blind lithotrity), Nitze and Hurry Fenwick (Cystoscopy), Sir Peter Freyer (open prostatectomy), Patrick Walsh (Radical Retropubic Prostatectomy), Roger Kirby and Prokar Dasgupta (Robotic prostatectomy in the UK). -

Urethro-Vesical Dysfunction in Progressive Autonomic Failure with Multiple System Atrophy

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1986;49:554-562 Urethro-vesical dysfunction in progressive autonomic failure with multiple system atrophy ROGER KIRBY,* CLARE FOWLER,* JOHN GOSLING,t ROGER BANNISTER$ From the Department of Urology, Middlesex Hospital,* London, The National Hospitalfor Nervous Diseases, London, and the Department ofAnatomy, University ofManchester,t UK SUMMARY Fourteen patients with progressive autonomic failure and multiple system atrophy have been investigated by urodynamic, electromyographic and neurohistochemical means and the results compared with a series of age-matched controls. Three fundamental abnormalities of lower urinary tract function have been identified: (1) Involuntary detrusor contractions in response to bladder filling. It is suggested that these may be the result of a loss of inhibitory influences from the corpus striatum and substantia nigra. (2) Loss of the ability to initiate a voluntary micturition reflex. This may reflect the degeneration of neurons in pontine and medullary nuclei and in the sacral inter- mediolateral columns. In addition, these studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in the density of acetylcholinesterase-containing nerves in bladder muscle. (3) Profound urethral dys- function. This appears to be partly due to a loss of proximal urethral sphincter tone, which causes bladder neck incompetence. In addition, the function of the striated component of the urethral sphincter is impaired. Individual motor units recorded from this muscle were clearly abnormal when compared with controls and suggested that reinnervation had occurred. We suggest that this is the result of degeneration of a specific group of sacral anterior horn cells known as Onuf's nucleus. The evidence that these particular motor units are affected, while others are spared, poses fundamental questions about the nature of selective vulnerability in degenerative diseases of the nervous system. -

University of Birmingham So Much Cost, Such Little Progress

University of Birmingham So Much Cost, Such Little Progress Bryan, Richard T; Kirby, Roger; O'Brien, Tim; Mostafid, Hugh DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.031 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Bryan, RT, Kirby, R, O'Brien, T & Mostafid, H 2014, 'So Much Cost, Such Little Progress', European urology, vol. 66, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.031 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked October 2015 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Queen Square Alumnus Association

QUEEN SQUARE ALUMNUS ASSOCIATION Issue 4 December 2012 Editor Mr David Blundred Teaching and E-Learning Administrator [email protected] Editorial Leads Professor Simon Shorvon Professor Andrew Lees Miss Jean Reynolds Ms Daniela Warr Schori Miss Pat Harris Professor Ian McDonald dŚĞ ŽƉŝŶŝŽŶƐ ĞdžƉƌĞƐƐĞĚ ŝŶ ƚŚĞ ŶĞǁ ƐůĞƩ Ğƌ ďLJ authors and interviewees do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Editor or the UCL /ŶƐƟƚƵƚĞŽĨE ĞƵƌŽůŽŐLJĂŶĚE ĂƟŽŶĂů, ŽƐƉŝƚĂůĨŽƌ Neurology and Neurosurgery. All photographs have been kindly provided by D ĞĚŝĐĂů/ůůƵƐƚƌĂƟŽŶ͕ Y ƵĞĞŶ^ƋƵĂƌĞ>ŝďƌĂƌLJĂŶĚ ƚŚĞĚŝƚŽƌƐƉƌŝǀ ĂƚĞĐŽůůĞĐƟŽŶ͘ Contents Editorial 02 News 03 Queen Square Alumnus A round-up of the latest news Association meeting 2013 from Queen Square Alumni News 09 Queen Square Alumnus Association Meeting 11 News, views and recollections from Programme details your fellow alumni Upcoming Events 12 Queen Square Interview 13 A sample of events on offer The Editor interviews Professor Clare over the next few months Fowler on her career at Queen Square Alumni Interview 18 The Editors Travels 20 Dr Andreas Moustris talks about his time at Queen Square An update on the Editors Travels Focus on the Dominican Republic 21 Wilsons Disease Centenary Symposium 23 Professor Jose Puello updates us on developments Professor Niall Quinn and Dr Ted Reynolds in the Dominican Republic speak about this event Out of the Archives 26 Photos from our Archives 28 Christmas recollections from 1906 A look at some of our photos from our archives Belfast Neurology 30 Front Cover Explained 33 Dr Stanley Hawkins talks about Neurology in the Nineteenth and A look at the front cover Early Twentieth Century 1 EDITORIAL The Queen square Alumnus Association Meeting July 2013 I am delighted to announce that we will be holding a two day Alumnus meeting on the 8th and 9th July 2013. -

Prostate Cancer and Diet Update Study Conclusion

prostate matters Newsletter of the Prostate Cancer Support Federation Issue 7 February 2010 Contents New Year, new layout Page 2 Report of the Great PSA Debate and a sponsor for our Page 3 PSA Debate continued Page 4 Prostate Cancer and new all colour newsletter! Diet Update Page 5 Diet and Lifestyle The Prostate Cancer Support Federation Changes Page 6 RADICALS Annual Conference & AGM Clinical Trial Page 7 The Great PSA Debate Questionnaire Analysis Report Living well with Page 8 National Cancer Patient Information Prostate Cancer Prescriptions Worried or concerned Saturday 24th April 2010 about prostate cancer? 11.00 to 4.45pm National Help at the Line 0845 601 0766 Penny Brohn Cancer Centre Chapel Pill Lane PM Editor: Roger Bacon email: [email protected] Pill, Bristol You can download this newsletter direct from our website. Go to: BS20 0HH www.prostatecancerfederation.org.uk/ ProstateMatters_latest.pdf Book by phone: 01243 572990 or online The Federation e mail address is: Full programme of speakers will be sent out to member groups [email protected] and published on our website when available It is intended to publish this www.prostatecancerfederation.org.uk/agm_2010.htm newsletter 4 times a year Newsletter Sponsored by Mediwatch “Providing the complete diagnostic solution for Urologists” The Great PSA Debate – November 10th 2009, Leamington Spa Over a hundred representatives of Invited speakers that attach to its use, in particular prostate cancer patient support Before the debate proper, the scene automatic biopsy and treatment of groups went to Leamington Spa was set by Dr Dennis Brennan, a men with a PSA above a notional th on 10 November 2009 to join with recently retired company doctor, threshold. -

A Comprehensive Review of Overactive Bladder Pathophysiology: on the Way to Tailored Treatment

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 75 (2019) 988– 1000 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.europeanurology.com Review – Female Urology – Incontinence – Editor’s Choice A Comprehensive Review of Overactive Bladder Pathophysiology: On the Way to Tailored Treatment Benoit Peyronnet a,*, Emma Mironska b, Christopher Chapple b, Linda Cardozo c, Matthias Oelke d, Roger Dmochowski e,Ge´rard Amarenco f, Xavier Game´ g, Roger Kirby h, Frank Van Der Aa i, Jean-Nicolas Cornu j a Department of Urology, University Hospital of Rennes, Rennes, France; b Department of Urology, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK; c Department of Urology, St. Antonius Hospital, Gronau, Germany; d Department of Urology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA; e Department of Neurourology, Tenon Hospital, Paris, France; f Department of Urogynaecology, King’s College Hospital, London, UK; g Department of Urology, University Hospital of Toulouse, Toulouse, France; h The Prostate Centre, London, UK; i Department of Urology, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; j Department of Urology, University Hospital of Rouen, Rouen, France Article info Abstract Article history: Context: Current literature suggests that several pathophysiological factors and mechanisms might Accepted February 28, 2019 be responsible for the nonspecific symptom complex of overactive bladder (OAB). Objective: To provide a comprehensive analysis of the potential pathophysiology underlying Associate Editor: detrusor overactivity (DO) and OAB. Evidence acquisition: A PubMed-based literature -

Achieving Effective Risk-Factor Modification in Men

Risk Factor Modification v2_Layout 1 20/05/2011 15:05 Page 1 TALKING POINTS 13 Achieving effective risk-factor modification in men MICHAEL KIRBY AND ROGER KIRBY Urological complaints in men provide healthcare professionals with an opportunity to modify risk factors, thus not only averting the progression of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia, but also reducing the hazards of cardiovascular events in men presenting with erectile dysfunction. he concept of ‘risk’ is not well will translate into Tappreciated by most men. In the premature business world, risk, when adroitly judged, morbidity and can lead to significant rewards. By mortality. contrast, most men tend to be somewhat risk averse, not only financially, but also Risk prediction more importantly in terms of approaching has become a hot their health. Attitudes between the sexes topic, not only in vary, as does their willingness to seek cardiovascular medical help and advice. Women tend to disease, but also in localised prostate Figure 1. Helping seek help earlier and are much more likely cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) patients counter obesity to confide in friends and relatives. and erectile dysfunction (ED), and there are by encouraging lifestyle modification major opportunities to advise corrective (patient handout available from When men eventually do present to us treatment and/or lifestyle modification www.trendsinurology.com) in the surgery or clinic, we need to take accordingly. the opportunity to think about their future risk and modify those things that PROSTATE CANCER are modifiable. A subgroup of patients presenting with localised prostate cancer can certainly be From middle age onwards we all carry stratified as high risk. -

TUF Matters Issue 12 Read More

ISSUE 12 TUF SPRING NEWS AND VIEWSmatters FROM THE UROLOGY FOUNDATION 2021 Bringing follow-up to the forefront Creating a lasting legacy Ending the suffering caused by urology disease theurologyfoundation.org TUFmatters ISSUE 12 | theurologyfoundation.org contents welcome to 03 Big Bake Recipe TUF matters Swap 04 Improving care and well-being across all Hello and welcome to urology TUF matters. 06 Save the Ball First I very much hope that you are keeping safe and well. We continue to live in uncertain times. When 08 Creating a lasting the pandemic first began last year we initially had legacy hopes of it being over by summer, and then by the end of the year. Now it is becoming apparent that 10 Bringing follow up Covid is something we might have to learn to live to the forefront with on an ongoing basis. Hospitals and GP practices have worked hard to make Covid-secure spaces and 12 Ticket to ride the message from urologists is clear: if you have any worries or symptoms please do not delay to seek 14 Supporting the next help or advice. Good outcomes and quality of life generation depend upon early diagnosis so don’t hesitate if you have any health concerns. 15 TUF Nuts Tuesday In the meantime, despite the stresses and strains of 2020, TUF continued to support the urology TUF Heroes 16 community and made a number of research and training awards last year, funding 10 research projects Dates for your diary 18 and supporting over 100 trainees to take part in online lectures and tutorials via the RSM. -

Urologic Robotic Surgery in Clinical Practice Prokar Dasgupta Editor

Urologic Robotic Surgery in Clinical Practice Prokar Dasgupta Editor Urologic Robotic Surgery in Clinical Practice Foreword by James O. Peabody and Mani Menon 123 Editor Prokar Dasgupta Department of Urology Guy’s Hospital London UK [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-84800-242-5 e-ISBN: 978-1-84800-243-2 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-84800-243-2 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2008936130 c Springer-Verlag London Limited 2008 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc., in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. Product liability: The publisher can give no guarantee for information about drug dosage and application thereof contained in this book. -

So Much Cost, Such Little Progress

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 66 (2014) 263–264 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.europeanurology.com Platinum Priority – Editorial Referring to the article published on pp. 253–262 of this issue So Much Cost, Such Little Progress Richard T. Bryan a,b,*, Roger Kirby c,d, Tim O’Brien e,f, Hugh Mostafid g,h a School of Cancer Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; b Royal Society of Medicine Section of Urology, London, UK; c The Prostate Centre, London, UK; d The Urology Foundation, London, UK; e Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; f British Association of Urological Surgeons Section of Oncology, London, UK; g Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, UK; h Action on Bladder Cancer, London, UK Urothelial bladder cancer (UBC) is burdensome for patients In this month’s issue of European Urology, Svatek et al. and expensive for health care providers [1]. Outcomes have provide a review of the costs and other considerations for changed little for three decades, despite significant these approaches and discuss key issues regarding the improvements in 5-yr survival rates for prostate and kidney wider economics of UBC care [6]. Their review represents a cancers during this period [1]. Patient pathways are useful overview for the practicing urologist. In particular, complex, prolonged, and practised in various permutations the authors demonstrate that there are large gaps in our at every stage: knowledge regarding the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of these approaches and a lack of sufficiently powered The investigation of patients with suspected UBC requires randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with expensive tools multiple diagnostic procedures [2,3]; various combina- having crept into everyday practice without the necessary tions of tests are used [4].