About Parkour As a Tool in a Humanitarian Life Skills Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHARTA Charta Parkourone

ParkourONE CHARTA Charta ParkourONE Preface The following Charta is addressed to all interested in Parkour, ParkourONE, the community and our work. It is a business card to make the ParkourONE community graspable for outsiders, convey contents, as well as unveil our opinions, intentions and structures for the purpose of transparency. We do not regard this Charta a corset in which we are wedged, however as a self-imposed standard to be compared with. Purpose of the Charta is to describe and illuminate the following areas: The history of Parkour is pivotal for the ParkourONE community. We want to narrate our know- ledge about the history of the origin of our art and how we experienced it or interpret it. We affiliate our understanding of Parkour and its associated values directly to David Belle and have great respect for the pioneers of the ADD-culture. Thus, we perceive ourselves as bearer of a spe- cific idea; Parkour cannot be redefined randomly but rather has its own (even conceptual) history. We distinctly declare: David Belle is a living person; as such he and his perception, likewise, will change. We follow David‘s original idea, however, not him as a „Guru“, leader or the like. In other words, even if David Belle would fundamentally modify his understanding of Parkour, our idea of it would basically remain unimpaired - we follow our own path, it is precisely this which we regard an important piece of the initial conception of Parkour. The next chapter recounts the structures of the ParkourONE community, the ParkourONE Com- pany and our own history of genesis. -

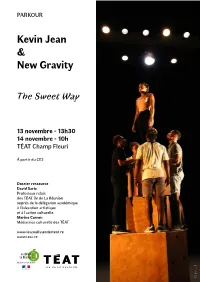

Kevin Jean & New Gravity

PARKOUR Kevin Jean & New Gravity The Sweet Way 13 novembre - 13h30 14 novembre - 10h TÉAT Champ Fleuri À partir du CE2 Dossier ressource David Sarie Professeur relais des TÉAT, île de La Réunion auprès de la délégation académique à l’éducation artistique et à l’action culturelle. Marine Carron Médiatrice culturelle des TÉAT www.lescoulissesdesteat.re www.teat.re 1 © iprod DOSSIER RESSOURCE SOMMAIRE P 3 - A propos du spectacle P 4 - Démarche artistique P 7 - A propos des artistes P 14 - Le parkour P 18 - Pistes pédagogiques Dossier ressource - The Sweet Way 2 A propos du spectacle The Sweet Way est le fruit d’une rencontre initiée par les TÉAT entre le chorégraphe Kevin Jean et les New Gravity, une équipe de traceurs qui font du parkour à La Réunion. Cette rencontre est celle de langages artistiques différents, d’histoires personnelles avec les failles intimes de chacun mais également d’un cheminement du travail des uns et des autres appelés logiquement à converger. Après Emergency chorégraphié par Jérôme Brabant en 2015, les New Gravity reviennent sur scène avec une création plus intimiste, moins acrobatique. Il s’agit de mettre l’énergie non plus au service de performances spectaculaires mais d’une démarche à la recherche de la douceur. Dans cette création, Kevin Jean poursuit un travail initié en 2016 avec Promesses du Magma vers des chorégraphies plus introspectives et apaisées. Il prend le contrepied de ses trois premiers spectacles, La 36ème chambre (2011), Derrière la porte verte (2012) et Des Paradis (2015) qui étaient centrés sur l’entrave et la contrainte. -

Kort Introduktion Til Parkour Og Freerunning

Kort introduktion til Parkour og Freerunning Parkour 'Parkour' eller 'Le Parkour' er en bevægelsesaktivitet, som handler om at udvikle sig fysisk og mentalt gennem naturlige og ekspressive bevægelser. Den grundlæggende ide bag bevægelserne er at bevæge sig gennem omgivelserne hurtigt og effektivt i flow, dvs. at komme fra punkt A til B, mest effektivt og hurtigst muligt, udelukkende ved brug af kroppen. Miljøet er oftest bymæssigt. Bygninger, gelænder, vægge anvendes til fremdrift på en alternativ måde. Det handler om at se udfordring og muligheder der hvor andre ser begrænsninger og funktionalitet. Parkourudøverne kaldes ’traceurs’, hvilket kan oversættes til projektil eller kugle, som henleder til udøvernes kontinuerlige bevægelser. En rigtig traceur har gjort parkour til en central del af hans livsstil, og lever derved efter filosofien om at opleve frihed. Parkour startede som en subkultur, der udviklede sig i de franske forstæder, men har siden spredt sig ud i hele verden via Internettet. Oprindelse Franskmanden David Belle betegnes som grundlæggeren af parkour. Belles far, Raymond Belle, var løjtnant i Vietnamkrigen. Til at træne sine soldater til at bevæge sig effektivt rundt i junglen, anvendte han træningssystemet ’methode naturalle1’, der grundlagdes af Georg Hébert (1875- 1957).2 Methode naturelle er kort fortalt et system af filosofiske idéer og fysiske metoder, der ontologisk knytter sig til Jean-Jacques Rousseaus (1712-1778) og Johan Gutsmuths (1759-1839) filantropiske tanker om at vende tilbage til naturen og dannelse af det hele menneske3. Systemet bygger på en holistisk verdensforståelse, og tager udgangspunkt i effektivitet, flow og hurtighed.4 Raymond Belle introducerede David Belle for ideerne bag dette træningssystem, hvilket han tog med ud på gaderne i de franske forstæder. -

The Phenomenological Aesthetics of the French Action Film

Les Sensations fortes: The phenomenological aesthetics of the French action film DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alexander Roesch Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Patrick Bray Dana Renga Copyrighted by Matthew Alexander Roesch 2017 Abstract This dissertation treats les sensations fortes, or “thrills”, that can be accessed through the experience of viewing a French action film. Throughout the last few decades, French cinema has produced an increasing number of “genre” films, a trend that is remarked by the appearance of more generic variety and the increased labeling of these films – as generic variety – in France. Regardless of the critical or even public support for these projects, these films engage in a spectatorial experience that is unique to the action genre. But how do these films accomplish their experiential phenomenology? Starting with the appearance of Luc Besson in the 1980s, and following with the increased hybrid mixing of the genre with other popular genres, as well as the recurrence of sequels in the 2000s and 2010s, action films portray a growing emphasis on the importance of the film experience and its relation to everyday life. Rather than being direct copies of Hollywood or Hong Kong action cinema, French films are uniquely sensational based on their spectacular visuals, their narrative tendencies, and their presentation of the corporeal form. Relying on a phenomenological examination of the action film filtered through the philosophical texts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Mikel Dufrenne, and Jean- Luc Marion, in this dissertation I show that French action cinema is pre-eminently concerned with the thrill that comes from the experience, and less concerned with a ii political or ideological commentary on the state of French culture or cinema. -

Parkour/Freerunning As a Pathway to Prosocial Change

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Parkour/Freerunning as a Pathway to Prosocial Change: A Theoretical Analysis By Johanna Herrmann Supervised by Prof Tony Ward A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forensic Psychology Victoria University of Wellington 2016 ii iii Acknowledgements Special thanks to my supervisor Prof Tony Ward for his constant support and constructive feedback throughout the pleasures and struggles of this project. His readiness to offer an alternative perspective has provided me with many opportunities to grow as a critical thinker, researcher, and as a person. I am grateful to Prof Devon Polaschek, Dr Clare-Ann Fortune, and all members of their lab for encouraging me to pursue an innovative research project, as well as for providing inspiration, insights and connections to other specialist research areas in offender rehabilitation. The German Academic Exchange Service deserves special mention for the financial support that allowed me to take up my dream course of study in the country that is farthest away from my home. Finally, I would like to thank Damien Puddle and Martini Miller for lively discussions, valuable feedback, and sharing the passion regarding research, parkour/freerunning, as well as youth development. iv v Abstract Parkour/freerunning is a training method for overcoming physical and mental obstacles, and has been proposed as a unique tool to engage youth in healthy leisure activities (e.g., Gilchrist & Wheaton, 2011). Although practitioners have started to utilise parkour/freerunning in programmes for youth at risk of antisocial behaviour, this claim is insufficiently grounded in theory and research to date. -

The Contemporary Sublime and the Culture of Extremes: Parkour and Finding the Freedom of the City

Amanda du Preez the contemporary sublime and the culture of extremes: parkour and finding the freedom of the city BIOGRAPHY Amanda du Preez completed her Doctoral studies at the University of South Africa in 2002 with the title Gendered Bodies and New Technologies. The thesis has one founding premise, namely that embodiment constitutes a non-negotiable prerequisite for human life. Over the past 15 years she has lectured at the University of Pretoria, University of South Africa, the Pretoria Technikon, and the Open Window Art Academy, on subjects ranging from Art History, Visual Communication, and Art Therapy to Open and Distance Learning. She is currently a Senior Lecturer at the University of Pretoria, in the Department of Visual Arts, and teaches Visual Culture and Art History. In 2005 she co-authored South African Visual Culture with J. van Eeden (Van Schaik: Pretoria). The following publications are forthcoming: Gendered Bodies and New Technologies: Re-thinking Embodiment in a Cyber Era (Unisa Press) and Taking a Hard Look: Gender and Visual Culture (Cambridge Scholars Press). Her field of expertise includes gender and feminist theories, virtual and cyber culture, bio-politics, new technologies, and film and 16 visual culture. → The aim is to explore and probe the possible ways in which the discourse of the sublime, as a modern aesthetic category, has mutated and morphed into the postmodern contemporary visual culture of extremes - extreme sports, extreme adventures, and extreme entertainment. The extreme activity of Le Parkour or obstacle-coursing, described by David Belle, its ‘founder’, as finding new and often dangerous ways through the city landscape – scaling walls, roof-running and leaping from building - to building, is identified as an interesting prospect for teasing out the postmodern contemporary visual culture of extremes. -

Re-Enchantment, Play, and Spirituality in Parkour

religions Article Tracing the Landscape: Re-Enchantment, Play, and Spirituality in Parkour Brett David Potter Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Sheridan College, Oakville, ON L6H 2L1, Canada; [email protected] Received: 2 August 2019; Accepted: 26 August 2019; Published: 28 August 2019 Abstract: Parkour, along with “free-running”, is a relatively new but increasingly ubiquitous sport with possibilities for new configurations of ecology and spirituality in global urban contexts. Parkour differs significantly from traditional sports in its use of existing urban topography including walls, fences, and rooftops as an obstacle course/playground to be creatively navigated. Both parkour and “free-running”, in their haptic, intuitive exploration of the environment retrieve an enchanted notion of place with analogues in the religious language of pilgrimage. The parkour practitioner or traceur/traceuse exemplifies what Michael Atkinson terms “human reclamation”—a reclaiming of the body in space, and of the urban environment itself—which can be seen as a form of playful, creative spirituality based on “aligning the mind, body, and spirit within the environmental spaces at hand”. This study will subsequently examine parkour at the intersection of spirituality, phenomenology, and ecology in three ways: (1) As a returning of sport to a more “enchanted” ecological consciousness through poeisis and touch; (2) a recovery of the lost “play-element” in sport (Huizinga); and (3) a recovery of the human body attuned to our evolutionary past. Keywords: parkour; free-running; religion; pilgrimage; poiesis; ecology; urban 1. Introduction Over the past two decades, the sport known as parkour has become a global phenomenon, with groups of practitioners or traceurs emerging from Paris to Singapore. -

Recognition Announcement Press Release Jan 2017

Pre-event press release Embargoed until 9am on Tuesday 10th January 2017 Parkour takes giant leap to become officially recognised sport The UK has becomes the first country in the world to officially recognise Parkour/Freerunning as a sport, after the Home Country Sports Councils approved Parkour UK’s application for recognition of the sport and the National Governing Body. Parkour, also known as Freerunning or Art du Deplacement, is the non-competitive physical discipline of training to move freely over and through any terrain using only the abilities of the body, principally through running, jumping, climbing and quadrupedal movement. In practice it focuses on developing the fundamental attributes required for such movement, which include functional strength and fitness, balance, spatial awareness, agility, coordination, precision, control and creative vision. Parkour/Freerunning motivates people to get active. Participants can take part in the sport whenever and wherever they want, without needing to meticulously manage their busy diaries, buy special equipment, join a club, or book a pitch or court. All you need is a pair of trainers and your imagination to #GiveParkourAGo! The recognition of Parkour/Freerunning as a sport & Parkour UK as the National Governing Body (NGB) by the Home Country Sports Councils - Sport England, Sport Northern Ireland, sportscotland, Sport Wales and UK Sport follows completion of the UK recognition process by Parkour UK. Parkour UK, was established in 2009 by the nation’s Parkour/Freerunning community and the City of Westminster. It began the formal recognition process in March 2013, with the pre application for recognition approved in March 2014. -

Parkour, the Affective Appropriation of Urban Space, and the Realvirtual

Parkour, The Affective Appropriation of Urban Space, and the Real/Virtual Dialectic Jeffrey L. Kidder∗ Northern Illinois University Parkour is a new sport based on athletically and artistically overcoming urban obsta- cles. In this paper, I argue that the real world practices of parkour are dialectically intertwined with the virtual worlds made possible by information and communi- cation technologies. My analysis of parkour underscores how globalized ideas and images available through the Internet and other media can be put into practice within specific locales. Practitioners of parkour, therefore, engage their immediate, physical world at the same time that they draw upon an imagination enabled by their on-screen lives. As such, urban researchers need to consider the ways that vir- tual worlds can change and enhance how individuals understand and utilize the material spaces of the city. EMPLACEMENT IN A VIRTUAL WORLD With the increasing integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) into our lives, more and more of our daily interactions take place “on screen” (Turkle 1995). Castells (1996) refers to this as a culture of real virtuality. In this process, the ex- periences of our physically situated, corporeal selves are becoming intertwined with the virtual presentation of our selves online (cf. Gottschalk 2010; Ito et al. 2010; Turkle 2011; Williams 2006). It is tempting, perhaps, to dichotomize on-screen and off-screen life. One is “real”—connected to the obdurate reality of time and space and hemmed in by biolog- ical limits and social inequalities (e.g., Robins 1995). The other is “virtual”—free-floating and filled with nearly limitless potential (e.g., Rheingold 1993). -

Martin Taylor

This matter is being dealt with by: Eugene Minogue Chief Executive Direct Line: +44 (0)7 920 793 728 Telephone: +44 (0)20 3544 5834 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.parkour.uk Date: Friday, 31 March 2017 President Morinari Watanabe Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique D Avenue de la Gare 12A a Case postale 630 t 1001 Lausanne e Switzerland : OPEN LETTER T h Dear President Morinari Watanabe, u r RE: ‘Development of a related FIG discipline’ based on Parkour/Freerunning s d I write from Parkour UK, the recognised National Governing Body (NGB) / National Federation for the recognised a sport of Parkour/Freerunning in the United Kingdom (appendix 1 – Letter of recognition from the UK Sports y Councils), regarding the encroachment and misappropriation of our sport by Fédération Internationale de , Gymnastique (FIG) via ‘development of a related FIG discipline’ based on Parkour/Freerunning, as detailed in your press release dated 24th February 2017, Lausanne (Sui), FIG Office. 3 0 As the recognised custodians of the recognised sport of Parkour/Freerunning in the UK and to protect and promote the integrity, rights, freedoms and interests of Traceurs/Freerunners (practitioners of our sport), our member M organisations & the UK community - as well as by legitimate extension the international Parkour/Freerunning a community - we feel that it is both necessary and expedient to provide some much needed clarification on r Parkour/Freerunning, such that our sport is neither misappropriated and/or encroached upon by FIG internationally c and/or nationally by any FIG member National Federations. h Clarification on Parkour/Freerunning; 2 0 What is a ‘sport’?: 1 7 The council of Europe definition of sport (Article 2): “Sport” means all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organised participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels. -

A Sociological Approach

NON-VIOLENT PROBLEM SOLVING IN PIERRE MOREL’S B13: A SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by: DEWAN PRIDITYO A 320 050 018 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2010 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study B13 film is one of the action films that tell about Paris, 2010, the government has walled in the ghettos of the city to contain crime. But things heat up when a super cop must go in and team up with a lone vigilante to fend off drug dealers and diffuse a bomb that threatens to kill millions. This had been made in 2002 directed by Pierre Morel, a man who has more talent of this work and was collaborate with two famous writers they are Luc Besson and Bibi Nacery. Both of them were good writers who have made many works. This film has 84 minutes of duration full action and adventure there. The big crime was cover there. In the middle of city, this film was setting in Paris building, on top of building, and in the police office also in the prison. The first time released on 10 November 2004 in French. An action crime film was created by the great hands and completed by two mean actors: David Belle (Leito) and Cyril Rafaely (Damien) with them acrobatic act (Parkour). Released on 2004 and on 2006 won one award from golden trailer for category of best foreign action trailer in New York. -

The Ultimate Book

150 mm 166 mm 166 mm 150 mm Boss - 328 Seiten 18,5 mm 2 mm Überhang The Ultimate The Ultimate & Parkour & Freerunning Parkour about the book FreerunningBook the authors The increasing number of followers of the two movement cultures, Parkour and Free- Jan Witfeld is a graduate in sports science and now • Always use your head first before giving free rein to your emotions or running, has given rise to the need for safe, methodical orientation, which the reader works as a school teacher. He discovered the Move moving a muscle. will find in this book. Artistic platform in 2003, and, two years later, Parkour • Always make sure that the “move” is safe. and Freerunning. He then went on to train as a Move Parkour, a new movement culture from France, is all about moving as efficiently as • Do not rush or make unpremeditated moves. Book Artistic instructor. possible between points A and B by sprinting fluently over obstacles. The sport of Free- • Never overestimate your ability. running has developed from it, involving developing and showing off the most creative, • Never practice demanding elements alone. extreme, flowing, acrobatic moves possible on obstacles. Ilona E. Gerling is a university lecturer at the German • Never practice alone in an unsafe and unfamiliar area. Someone must This book contains precise illustrations for the teaching of all basic techniques, easy-to- Sports University in Cologne and speaks at internatio- always be present in case of emergency. follow movement breakdowns and methodical tips for indoor and outdoor training. All nal gymnastics congresses and forums.