ACAD Cadillac Mountain Summit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2016 Volume 21 No

Fall/Winter 2016 Volume 21 No. 3 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities Friends of Acadia Journal Fall/Winter 2016 1 President’s Message FOA AT 30 hen a handful of volunteers And the impact of this work extends at Acadia National Park and beyond Acadia: this fall I attended a Wforward-looking park staff to- conference at the Grand Canyon, where gether founded Friends of Acadia in 1986, I heard how several other friends groups their goal was to provide more opportuni- from around the country are modeling ties for citizens to give back to this beloved their efforts after FOA’s best practices place that gave them so much. Many were and historic successes. Closer to home, avid hikers willing to help with trail up- community members in northern Maine keep. Others were concerned about dwin- have already reached out to FOA for tips dling park funding coming from Washing- as they contemplate a friends group for the ton. Those living in the surrounding towns newly-established Katahdin Woods and shared a desire to help a large federal agen- Waters National Monument. cy better understand and work with our As the brilliant fall colors seemed to small Maine communities. hang on longer than ever at Acadia this These visionaries may or may not year, I enjoyed a late-October morning on have predicted the challenges and the Precipice Trail. The young peregrine opportunities facing Acadia at the dawn FOA falcons had fledged, and the re-opened trail of its second century—such as climate featured a few new rungs and hand-holds change, transportation planning, cruise and partners whom we hope will remain made possible by a generous FOA donor. -

Acadia Activities Brochure

Acadia Mt Desert Island, Maine Samuel E. Lux June 2019 edition planyourvisit/conditions.htm or by searching http://www.mdislander.- Hiking com, the local newspaper, for “precipice trail”. Neither is reliably The hiking in Acadia is, to my mind, up-to-date. The Harbor Walk in Bar the best in America. The approxi- Harbor and the walk along Otter mately 135 miles of trails are beauti- Point (Ocean trail) are both very fully marked and maintained. Many beautiful and very easy. Another have granite steps, or iron ladders or short, easy hike is to Beech Cliffs railings to help negotiate difficult/ from the top of Beech mountain. dangerous spots. They range from road. Only 0.3 mile and great views. flat to straight up. And you get the Kids also love the short walk to the Fig. 1. View of Sand Beach from best views with the least work of any rocky coast and myriad tide pools on part way up Beehive trail trail system anywhere. Beehive to the Wonderland trail. Couch potatoes Gorham mountain and Cadillac can drive to the top of Cadillac Cliffs, then walk back along shore mountain, the highest point in the (Ocean trail), Precipice (appropriately park. Views are worth it. named), and the Jordan Cliffs trail Excellent Circle Hikes followed by a walk back down South Ridge of Penobscot mountain trail are Beehive-Gorham-Ocean Drive my favorites, but there are dozens of Park at Sand Beach on the Park Loop great ones, at least 50 overall. For Road. Do this hike early in the day kids over 6 to 7 years the Beehive trail before the crowds arrive. -

Nine Mile Thru Trail by Tom Sidar Long Cove to Schoodic Beach Long Pond Stream Runs North from the Outlet of Long Pond in the Town of Sullivan

Protecting the Land You Love NO. 58 SPRING 2013 Nine Mile Thru Trail by Tom Sidar Long Cove to Schoodic Beach Long Pond Stream runs north from the outlet of Long Pond in the town of Sullivan. Bounded by steep, hard granite ledges on the east, clear water runs in sparkling riffles and drops over miniature falls forming small pools and eddies that flow over fallen leaves and broken birch. Fur- ther along, the water slows and runs through dream-like, mossy banks of cedar swamp with deer tracks im- printed along the stream bank. December 30, 2011. Phillip Dunbar and I are walking north on Long Pond Brook. This is Dunbar land, hun- BROOKS dreds of acres of it, passed through ROB the generations. Phillip knows this land well. He tells me that, as a boy, PHOTO he would hunt and fish these waters and woods until daylight faded. This aerial photo shows the whole landscape of Long Pond to Schoodic and north. I am here for Frenchman Bay Conservancy. We are interested in The vision of this thru trail that once seemed purchasing a portion of this land as a link in a hiking trail that would be dreamy is starting to come into focus. open to the public from Old Route Over the past eight years, thanks and I am left to my own meandering One at Long Cove in Sullivan all the to the generosity of Land For Maine’s thoughts. “There are miles and miles way to the State of Maine Reserve Future, our members and friends, of habitat for wildlife like partridge, Land on the summit of Schoodic FBC has acquired the Schoodic Bog deer, snowshoe hare, brook trout, Mountain. -

Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program

Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program i Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program Prepared for the State Planning Office by Terry DeWan Terrence J. DeWan & Associates Landscape Architects Yarmouth, Maine October 2008 Printed Under Appropriation # 013-07B-3850-008201-8001 i Credits Prinicpal Author: Terry DeWan, Terrence J. Permission to use historic USGS maps from DeWan & Associates, Yarmouth, Maine University of New Hampshire Library web . with assistance from Dr. James Palmer, Es- site from Maptech, Inc. sex Junction, Vermont and Judy Colby- George, Spatial Alternatives, Yarmouth, This project was supported with funding Maine. from the Maine Coast Protection Initiative’s Implementation Grants program. The A project of the Maine State Planning Of- Maine Coast Protection Initiative is a first- fice, Jim Connors, Coordinator. of-its kind public-private partnership de- signed to increase the pace and quality of Special Thanks to the Maine Coastal Pro- land protection by enhancing the capacity gram Initiative (MCPI) workgroup: of Maine’s conservation community to pre- serve the unique character of the Maine • Judy Gates, Maine Department of coast. This collaborative effort is led by the Transportation Land Trust Alliance, NOAA Coastal Serv- • Bob LaRoche, Maine Department of ices Center, Maine Coast Heritage Trust, the Transportation Maine State Planning Office, and a coalition • Deb Chapman, Georges River Land of supporting organizations in Maine. Trust • Phil Carey, Land Use Team, Maine Printed Under Appropriation # 013-07B- State Planning Office 3850-008201-8001 • Stephen Claesson, University of New Hampshire • Jim Connors, Maine State Planning Office (Chair) • Amy Winston, Lincoln County Eco- nomic Development Office • Amy Owsley, Maine Coastal Planning Initiative Coordinator Maine State Planning Office 38 State House Station Photography by Terry DeWan, except as Augusta, Maine 04333 noted. -

The Regions of Maine MAINE the Maine Beaches Long Sand Beaches and the Most Forested State in America Amusements

the Regions of Maine MAINE The Maine Beaches Long sand beaches and The most forested state in America amusements. Notable birds: Piping Plover, Least Tern, also has one of the longest Harlequin Duck, and Upland coastlines and hundreds of Sandpiper. Aroostook County lakes and mountains. Greater Portland The birds like the variety. and Casco Bay Home of Maine’s largest city So will you. and Scarborough Marsh. Notable birds: Roseate Tern and Sharp-tailed Sparrow. Midcoast Region Extraordinary state parks, islands, and sailing. Notable birds: Atlantic Puffin and Roseate Tern. Downeast and Acadia Land of Acadia National Park, national wildlife refuges and state parks. Notable birds: Atlantic Puffin, Razorbill, and The Maine Highlands Spruce Grouse. Maine Lakes and Mountains Ski country, waterfalls, scenic nature and solitude. Notable birds: Common Loon, Kennebec & Philadelphia Vireo, and Moose River Downeast Boreal Chickadee. Valleys and Acadia Maine Lakes Kennebec & and Mountains Moose River Valleys Great hiking, white-water rafting and the Old Canada Road scenic byway. Notable birds: Warbler, Gray Jay, Crossbill, and Bicknell’s Thrush. The Maine Highlands Site of Moosehead Lake and Midcoast Mt. Katahdin in Baxter State Region Park. Notable birds: Spruce Grouse, and Black-backed Woodpecker. Greater Portland and Casco Bay w. e. Aroostook County Rich Acadian culture, expansive agriculture and A rich landscape and s. rivers. Notable birds: Three- cultural heritage forged The Maine Beaches toed Woodpecker, Pine by the forces of nature. Grossbeak, and Crossbill. 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Scale of Miles Contents maine Woodpecker, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Philadelphia Vireo, Gray Jay, Boreal Chickadee, Bicknell’s Thrush, and a variety of warblers. -

Discover New Places to Hike, Bike

Allagash Falls by Garrett Conover Explore MAINE 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE: Discover New Places to Hike, Bike, Swim, & More Favorite Protected Places Where in Maine do you want to go this summer? This year’s edition of Explore Maine offers spectacular places personally picked by NRCM staff, board, and members who know them well. Working together, over the last Books & Blogs 60 years, we helped ensure these places would be always be protected, for generations to come. We hope by NRCM Members you’ll make time to enjoy any and all of these recommendations. For even more ideas, visit our online Explore Maine map at www.nrcm.org. Cool Apps It is also our pleasure to introduce you to books and blogs by NRCM members. Adventure books, Explore Great Maine Beer biographies, children’s books, poetry—this year’s collection represents a wonderful diversity that you’re sure to enjoy. Hear first-hand from someone who has taken advantage of the discount many Maine sporting camps Maine Master provide to NRCM members. Check out our new map of breweries who are members of our Maine Brewshed Naturalist Program Alliance, where you can raise a glass in support of the clean water that is so important for great beer. And Finding Paradise we’ve reviewed some cool apps that can help you get out and explore Maine. Enjoy, and thank you for all you do to help keep Maine special. Lots More! —Allison Wells, Editor, Senior Director of Public Affairs and Communications Show your love for Explore Maine with NRCM a clean, beautiful Paddling, hiking, wildlife watching, cross-country skiing—we enjoy spending time in Maine’s great outdoors, and you’re invited to join us! environment Find out what’s coming up at www.nrcm.org. -

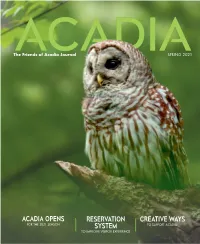

Spring 2021 Spring Creative Ways Ways Creative

ACADIA 43 Cottage Street, PO Box 45 Bar Harbor, ME 04609 SPRING 2021 Volume 26 No. 2 SPRING 2021 Volume The Friends of Acadia Journal SPRING 2021 MISSION Friends of Acadia preserves, protects, and promotes stewardship of the outstanding natural beauty, ecological vitality, and distinctive cultural resources of Acadia National Park and surrounding communities for the inspiration and enjoyment of current and future generations. VISITORS enjoy a game of cribbage while watching the sunset from Beech Mountain. ACADIA OPENS RESERVATION CREATIVE WAYS FOR THE 2021 SEASON SYSTEM TO SUPPORT ACADIA TO IMPROVE VISITOR EXPERIENCE ASHLEY L. CONTI/FOA friendsofacadia.org | 43 Cottage Street | PO Box 45 | Bar Harbor, ME | 04609 | 207-288-3340 | 800 - 625- 0321 PURCHASE YOUR PARK PASS! Whether walking, bicycling, riding the Island Explorer, or driving through the park, we all must obtain a park pass. Eighty percent of all fees paid in Acadia National Park stay in Acadia, to be used for projects that directly benefit park visitors and resources. BUY A PASS ONLINE AND PRINT Acadia National Park passes are available online: before you arrive at the park. This www.recreation.gov/sitepass/74271 allows you to drive directly to a Annual park passes are also available at trailhead/parking area & display certain Acadia-area town offices and local your pass from your vehicle. chambers of commerce. Visit www.nps.gov/acad/planyourvisit/fees.htm IN THIS ISSUE 10 8 12 20 18 FEATURES 6 REMEMBERING DIANNA EMORY Our Friend, Conservationist, and Defender of Acadia By David -

History of the Bar Harbor Water Company: 1873-2004

HISTORY OF THE BAR HARBOR WATER COMPANY 1873-2004 By Peter Morrison Crane & Morrison Archaeology, in association with the Abbe Museum Prepared for the National Park Service November, 2005 Frontispiece ABSTRACT In 1997, the Bar Harbor Water Company’s oldest major supply pipe froze and cracked. This pipe, the iron 12" diameter Duck Brook line was originally installed in 1884. Acadia National Park owns the land over which the pipe passes, and the company’s owner, the Town of Bar Harbor, wishes to hand over ownership of this pipe to the Park. Before this could occur, the Maine Department of Environmental Testing performed testing of the soil surrounding the pipe and found elevated lead levels attributable to leaching from the pipe’s lead joints. The Park decided that it would not accept responsibility for the pipe until the lead problem had been corrected. Because the pipe lies on Federally owned land, the Park requested a study to determine if the proposed lead abatement would affect any National Register of Historic Places eligible properties. Specifically, the Park wished to know if the Water System itself could qualify for such a listing. This request was made pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended. The research will also assist the Park in meeting obligations under Section 110 of the same act. Intensive historical research detailed the development of the Bar Harbor Water Company from its inception in the wake of typhoid and scarlatina outbreaks in 1873 to the present. The water system has played a key role in the growth and success of Bar Harbor as a destination for the east coast’s wealthy elite, tourists, and as a center for biological research. -

Randonnée Pédestre Le Maine

Index Les numéros de page en gras renvoient aux cartes. A Blueberry Mountain (région d’Evans Notch) 8 Abbe Museum (Acadia National Park) 29 Bubble – Pemetic Trail (Pemetic Mountain) 35 Abol Trail (Mount Katahdin) 24 Acadia Mountain Trail (Acadia C National Park) 36 Cadillac Mountain (Acadia National Acadia National Park 26,, 27 Park) 33 Appalachian Trail 6 Cathedral Trail (Mount Katahdin) 23 Chimney Pond Trail (Mount B Katahdin) 22 Baldface Circle (région d’Evans Notch) 10 D Bar Harbor Shore Path (Acadia Deer Hill (région d’Evans Notch) 10 National Park) 31 Dorr Mountain Trail (Acadia Bar Island (Acadia National Park) National Park) 31 31 Doubletop Mountain (Baxter State Baxter Peak (Helon Taylor Trail) Park) 26 (Mount Katahdin) 21 Dudley Trail (Mount Katahdin) 23 Baxter State Park 16, 17 A - Beachcroft Trail (Mount E Champlain) 31 East Royce Mountain (région Index Beech Mountain Trail (Acadia d’Evans Notch) 8 National Park) 37 Evans Notch, région d’ 7,, 9 Bigelow Mountain (région du mont Sugarloaf) 15 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782765828518 F K Flying Mountain Trail (Acadia Knife Edge Trail (Mount Katahdin) 22 National Park) 36 Frenchman’s Bay (Bar Harbor) 29 L Ledge Trail (Mount St. Sauveur) 36 G George B. Dorr Museum of Natural M History (Acadia National Maine 3,, 4 Park) 29 Mont Sugarloaf, région du 11,, 13 Gorham Mountain Trail (Acadia National Park) 33 Mount Abraham (région du mont Sugarloaf) 12 Great Head Trail (Acadia National Park) 32 Mount Champlain (Acadia National Park) 31 H Mount Coe (Baxter State Park) 25 Hamlin Peak (Mount Katahdin) 22 Mount Katahdin (Baxter State Park) 21 Hunt Trail (Mount Katahdin) 24 Mount St. -

Ellsworth Com Prehensive Plan Update 2004

ELLSWORTH COM PREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE November 2004 ELLSWORTH COM PREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE 2004 Prepared by the Ellsworth Comprehensive Planning Committee: Karen Hawes, Chairman Anne M. Hayes, Co-Chairman Nancy Alexander Ralph Buckminster Anne T. Hayes Debbie Hogan-Albert Brett Johnston Pat Jude Greg Lounder Daniel McClellan Victor Rydlizky Holly Shea Beth Smart Keith Smith Michele Gagnon, City Planner Timothy J. King, former City Manager Patricia Ryder, former Administrative Assistant Ellen Hathaway, former Administrative Assistant With technical assistance from the Hancock County Planning Commission Funding provided by Maine State Planning Office and the City of Ellsworth INDEX FOR COM PREHENSIVE PLAN CITY OF ELLSWORTH This index indicates where the proposed plan addresses the requirements of the Comprehensive Planning and Land Use Regulation Act (30-A M.R.S.A. Section 4326). Requirements I. Inventory and Analysis Section A. Population.......................................................................................................... A1-A8 B. Economy .............................................................................................................B1-B7 C. Housing...............................................................................................................C1-C8 D. Transportation … … … … ................................................................................ D1-D9 E. Existing Land Use Plan … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … .................. E1-E7 F. Public Services and Facilities)...........................................................................F1-F13 -

Winter 2015 Volume 20 No

Winter 2015 Volume 20 No. 3 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities Friends of Acadia Journal Winter 2015 1 Ways You Can Give Every gift, however large or small, helps further Friends of Acadia’s mission to preserve and protect Acadia National Park. Please consider these options for providing essential financial support to Friends of Acadia: Gift of Cash or Marketable Securities: Mail a check, payable to Friends of Acadia, to P.O. Box 45, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 or visit friendsofacadia.org to give online. Call 800-625-0321 or visit our website for instructions on giving appreciated securities. Gift of Retirement Assets: Designate FOA as a beneficiary of your IRA, 401(k), or other retirement asset. Gift of Property: Give real estate, boats, artwork, or other property to Friends of Acadia. Gift Through a Bequest in Your Will: Add Friends of Acadia as a beneficiary in your will. Your legacy will include a better future for Acadia. Ask your financial planner about possible tax benefits of your gift. For more information about how you can help support Friends of Acadia, contact Lisa Horsch Clark, Director of Development & Donor Relations, at 207-288-3340 or [email protected], or visit www.friendsofacadia.org President’s Message Using a Milestone to RediRect the Road or many of us, a birthday ending superintendent, Kevin Schneider, on in a zero is not something we look the job and contributing immediately to Fforward to. My recent passage into this important work. While I had little my fifties included a fair share of angst and doubt that the Acadia posting would at- gray hair. -

Spring 2015 (995 KB PDF)

Maine Chapter NON-PROFIT Appalachian Mountain Club U.S.-POSTAGE PO Box 1534 P A I D Portland, Maine 04104 PORTLAND,-ME PERMIT NO. 454 WILDERNESS MATTERS VOLUME XXXX • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 Appalachian Mountain Club Protects 4,311 Acres in Maine with Baker Mountain Purchase Scenic and ecologically significant lands on and around Baker Mountain in the 100-Mile Wilderness region near Greenville are now permanently protected following purchases by the AMC in late January, with assistance from The Nature Conservancy (TNC). The purchases by the nation’s oldest conservation and recreation organization conserve the second highest peak in Maine between Bigelow Mountain and Katahdin, as well as the headwaters of the West Branch of the Pleasant River, a vibrant wild brook trout fishery. The property lies within an unfragmented roadless area of mature hardwood and softwood forest, which also includes the preferred habitat of the rare Bicknell’s thrush. “Baker Mountain was surrounded by conservation lands, but the Baker Mountain tract itself was not protected. It was ‘the hole in the doughnut,’ and with this purchase, AMC and its conservation partner, TNC, have ensured that this ecologically significant land will be protected,” said AMC Senior Vice President Walter Graff. The land will be managed for a variety of uses, including recreation, habitat protection, and Photo by Noah Kleiner sustainable forestry. AMC will be providing Prentiss & Carlisle Group and Plum Creek Timber conservation easement on the first parcel covering pedestrian access to the land. Co., and a separate parcel comprising 1,200 acres about three-quarters of Baker Mountain, including AMC purchased two adjacent parcels abutting its from Plum Creek.