The Surprising Bunts and Smuts: “Still a Threat After All These Years”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ustilago: Habitat, Symptoms and Reproduction | Teliomycetes

Ustilago: Habitat, Symptoms and Reproduction | Teliomycetes For B.Sc. Botany 1st By Dr. Meenu Gupta Assistant Professor Botany J.D.W.C. Patna 1. Habit and Habitat of Ustilago: Ustilago, the largest genus of the family Ustilaginaceae is represented by more than 400 cosmopolitan species. Butler and Bisby (1958) reported 108 species from India. All species are parasitic and infect the floral parts of wheat, barley, oat, maize, sugarcane, Bajra, rye and wild grasses. The name Ustilago has been derived from a Latin word ustus meaning ‘burnt’ because the members of the genus produce black, sooty powdery mass of spores on the host plant parts imparting them a ‘burnt’ appearance. This black dusty mass of spores resembles soot or smut, therefore, commonly it is also known as smut fungus. The fungus is of much economic importance, because it causes heavy loss to various economically important plants. This genus is very common in U.P., Bihar, Punjab and Madhya Pradesh. 2. Symptoms of Ustilago: The symptoms appear only on the floral parts. The floral spikes turn black and remain filled with the smut spores. Ustilago produces two main types of symptoms: 1. The blackish powder of spores is easily blown away by the wind, leaving a bare stalk of inflorescence (Fig. 1 B). Species showing such symptoms are called loose smuts e.g., (a) Loose smut of oat caused by U. avenae (b) Loose smut of barley caused by U. nuda (c) Loose smut of wheat caused by U. nuda var. tritici. (Fig. 13A, B). (d) Loose smut of doob grass caused by U. -

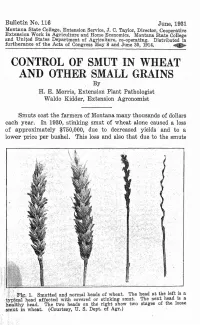

CONTROL of SMUT in WHEAT and OTHER SMALL GRAINS by H

Bulletin No. 116 June, 1931 Montana State College, Extension Service, J. C. Taylor, Director, Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics. Montana State College and Uni~ed States Department of Agriculture, co-operating. Distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress ~ay 8 and June 30, 1.914. ~ CONTROL OF SMUT IN WHEAT AND OTHER SMALL GRAINS By H. E. Morris, Extension Plant Pathologist Waldo Kidder, Extension Agronomist Smuts cost the farmers of Montana many thousands of dollars each year. In 1930, stinking smut of wheat alone caused a loss of approximately $750;000, due to decreased yields and to a lower price per bushel. This loss and also that due to the smuts {..:Fig. 1. Smutted and normal heads of wheat. The head at the left ,is a typi:cal head affected with covered or stinking smut, The next, head IS a he'althy head. The two heads on the right show two stages of the loose smut in wheat. (-Courtesy,D. S. Dept. of Agr.) . ,( 2 MONTANA EXTENSION SERVICE of oats, barley and rye may be largely prevented by adopting the methods of seed treatment described in this bulletin. What Is Smut Smut is produced by a small parasitic plant, mould-like in appearance, belonging to a group called fungi (Fig. 2). Smut lives most of its life within and at the expense of the wheat plant. The smut powder, so familiar to all, is composed of myriads of spores which correspond to seeds in the higher plants. In the process of harvesting and threshing, these spores are dis· I Fig'. -

The History, Fungal Biodiversity, Conservation, and Future Volume 1 · No

IMA FungUs · vOlume 1 · no 2: 123–142 The history, fungal biodiversity, conservation, and future ARTICLE perspectives for mycology in Egypt Ahmed M. Abdel-Azeem Botany Department, Faculty of Science, University of Suez Canal, Ismailia 41522, Egypt; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Records of Egyptian fungi, including lichenized fungi, are scattered through a wide array Key words: of journals, books, and dissertations, but preliminary annotated checklists and compilations are not checklist all readily available. This review documents the known available sources and compiles data for more distribution than 197 years of Egyptian mycology. Species richness is analysed numerically with respect to the fungal diversity systematic position and ecology. Values of relative species richness of different systematic and lichens ecological groups in Egypt compared to values of the same groups worldwide, show that our knowledge mycobiota of Egyptian fungi is fragmentary, especially for certain systematic and ecological groups such as species numbers Agaricales, Glomeromycota, and lichenized, nematode-trapping, entomopathogenic, marine, aquatic and coprophilous fungi, and also yeasts. Certain groups have never been studied in Egypt, such as Trichomycetes and black yeasts. By screening available sources of information, it was possible to delineate 2281 taxa belonging to 755 genera of fungi, including 57 myxomycete species as known from Egypt. Only 105 taxa new to science have been described from Egypt, one belonging to Chytridiomycota, 47 to Ascomycota, 55 to anamorphic fungi and one to Basidiomycota. Article info: Submitted: 10 August 2010; Accepted: 30 October 2010; Published: 10 November 2010. INTRODUCTION which is currently accepted as a working figure although recognized as conservative (Hawksworth 2001). -

Archaeobotanical Evidence of the Fungus Covered Smut (Ustilago Hordei) in Jordan and Egypt

ANALECTA Thijs van Kolfschoten, Wil Roebroeks, Dimitri De Loecker, Michael H. Field, Pál Sümegi, Kay C.J. Beets, Simon R. Troelstra, Alexander Verpoorte, Bleda S. Düring, Eva Visser, Sophie Tews, Sofia Taipale, Corijanne Slappendel, Esther Rogmans, Andrea Raat, Olivier Nieuwen- huyse, Anna Meens, Lennart Kruijer, Harmen Huigens, Neeke Hammers, Merel Brüning, Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Pieter van de Velde, Hans van der Plicht, Annelou van Gijn, Miranda de Kreek, Eric Dullaart, Joanne Mol, Hans Kamermans, Walter Laan, Milco Wansleeben, Alexander Verpoorte, Ilona Bausch, Diederik J.W. Meijer, Luc Amkreutz, Bertil van Os, Liesbeth Theunissen, David R. Fontijn, Patrick Valentijn, Richard Jansen, Simone A.M. Lemmers, David R. Fontijn, Sasja A. van der Vaart, Harry Fokkens, Corrie Bakels, L. Bouke van der Meer, Clasina J.G. van Doorn, Reinder Neef, Federica Fantone, René T.J. Cappers, Jasper de Bruin, Eric M. Moormann, Paul G.P. PRAEHISTORICA Meyboom, Lisa C. Götz, Léon J. Coret, Natascha Sojc, Stijn van As, Richard Jansen, Maarten E.R.G.N. Jansen, Menno L.P. Hoogland, Corinne L. Hofman, Alexander Geurds, Laura N.K. van Broekhoven, Arie Boomert, John Bintliff, Sjoerd van der Linde, Monique van den Dries, Willem J.H. Willems, Thijs van Kolfschoten, Wil Roebroeks, Dimitri De Loecker, Michael H. Field, Pál Sümegi, Kay C.J. Beets, Simon R. Troelstra, Alexander Verpoorte, Bleda S. Düring, Eva Visser, Sophie Tews, Sofia Taipale, Corijanne Slappendel, Esther Rogmans, Andrea Raat, Olivier Nieuwenhuyse, Anna Meens, Lennart Kruijer, Harmen Huigens, Neeke Hammers, Merel Brüning, Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Pieter van de Velde, Hans van der Plicht, Annelou van Gijn, Miranda de Kreek, Eric Dullaart, Joanne Mol, Hans Kamermans, Walter Laan, Milco Wansleeben, Alexander Verpoorte, Ilona Bausch, Diederik J.W. -

Color Plates

Color Plates Plate 1 (a) Lethal Yellowing on Coconut Palm caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen. (b, c) Tulip Break on Tulip caused by Lily Latent Mosaic Virus. (d, e) Ringspot on Vanda Orchid caused by Vanda Ringspot Virus R.K. Horst, Westcott’s Plant Disease Handbook, DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2141-8, 701 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 702 Color Plates Plate 2 (a, b) Rust on Rose caused by Phragmidium mucronatum.(c) Cedar-Apple Rust on Apple caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Color Plates 703 Plate 3 (a) Cedar-Apple Rust on Cedar caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi.(b) Stunt on Chrysanthemum caused by Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid. Var. Dark Pink Orchid Queen 704 Color Plates Plate 4 (a) Green Flowers on Chrysanthemum caused by Aster Yellows Phytoplasma. (b) Phyllody on Hydrangea caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen Color Plates 705 Plate 5 (a, b) Mosaic on Rose caused by Prunus Necrotic Ringspot Virus. (c) Foliar Symptoms on Chrysanthemum (Variety Bonnie Jean) caused by (clockwise from upper left) Chrysanthemum Chlorotic Mottle Viroid, Healthy Leaf, Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid, Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid, and Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (Mild Strain) 706 Color Plates Plate 6 (a) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Dieffenbachia caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi.(b) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Philodendron caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi Color Plates 707 Plate 7 (a) Common Leafspot on Boston Ivy caused by Guignardia bidwellii.(b) Crown Gall on Chrysanthemum caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens 708 Color Plates Plate 8 (a) Ringspot on Tomato Fruit caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus. (b, c) Powdery Mildew on Rose caused by Podosphaera pannosa Color Plates 709 Plate 9 (a) Late Blight on Potato caused by Phytophthora infestans.(b) Powdery Mildew on Begonia caused by Erysiphe cichoracearum.(c) Mosaic on Squash caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus 710 Color Plates Plate 10 (a) Dollar Spot on Turf caused by Sclerotinia homeocarpa.(b) Copper Injury on Rose caused by sprays containing Copper. -

Common Diseases of Small Grains and Their Management

Common Diseases of Small Grains and Their Management Gary C. Bergstrom Cornell University Section of Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Central New York Small Grains Workshop February 3, 2015 West Winfield, NY Plant Disease: A condition of a plant of abnormal growth or function Plant Pathogen: A living organism that can incite plant disease Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University When a microbe feeds on a: It is called a: Living host parasite Non-living host saprophyte When a pathogen: It is called a: Gets its nutrients from biotroph living cells Kills host cells before necrotroph acquiring nutrients Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Causal agents (pathogens) of infectious plant diseases • FUNGUS • OOMYCETE • BACTERIUM • VIRUS • NEMATODE Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Factors affecting disease epidemiology and management • Pathogen dissemination potential – (long-distance, regional, local) • Survival in debris • Vector relationship • Favorable environment Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Methods of disease management • Cultural (e.g., crop rotation) • Resistance (e.g., resistant or tolerant varieties) • Biological (e.g., biopesticides) • Chemical (e.g., fungicide seed treatment) • Regulatory (e.g., seed certification) Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Yellow dwarf of cereals and grasses Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Yellow dwarf of cereals and grasses • Pathogen: Barley yellow dwarf luteovirus and Cereal yellow dwarf polerovirus strains • Host range: all grasses • Symptoms: leaves yellow to red or purple; stunting • Conditions: early planting; large aphid populations • Survival: in infected aphids and grasses • Spread: by aphids (short & long distance) • Management:plant after Hessian fly free date, systemic seed insecticides Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Soilborne viruses © G.C. Bergstrom Gary C. -

Control of Loose Smut of Barley Richard Mullington Lewis Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1962 Control of loose smut of barley Richard Mullington Lewis Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Richard Mullington, "Control of loose smut of barley " (1962). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 2102. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/2102 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 63-1587 microfilmed exactly as received LEWIS, Richard Mullington, 1920- CONTROL OF LOOSE SMUT OF BARLEY. Iowa State University of Science and Technology Ph.D., 1962 Agriculture, plant pathology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CONTROL OF LOOSE SMUT OF BARLEY by Richard Mullington Lewis A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Plant Pathology Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge of Major Signature was redacted for privacy. Head of Major D rtment Signature was redacted for privacy. D^ân of Grad lollege Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa 1962 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 PERTINENT LITERATURE 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 6 Materials 6 Methods of Application 7 Seed Treatment Evaluations 12 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS 15 1952 Results 15 1953 Results 18 195m- Results 24 1955 Results 39 DISCUSSION 41 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 48 LITERATURE CITED 51 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 APPENDIX 54 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. -

Topic – Loose Smut of Wheat

Course – M. Sc. Botany Part 1 Paper III Topic – Loose Smut of Wheat Prepared by – Dr. Santwana Rani Coordinated by – Prof. (Dr.) Shyam Nandan Prasad Loose Smut of Wheat ➢ The disease loose smut of wheat is caused by ustilago nuda tritici. ➢ Incidence is more in north than in south India. ➢ Country wide loss is about 2-3%of total yield. ➢ There was a loose smut epidemic in Punjab, Haryana and western U.P. in 1970-75. Distribution: ➢ All wheat growing regions of India. ➢ Particularly in Punjab, Haryana, U.P. and certain regions of M.P. Symptoms: ➢ Symptoms appear after ear emergence. ➢ Diseased ear emerged first than normal in some varieties ➢ Mostly all ears is converted into a black mass of spores ➢ All the floral parts of the head, except the rachis and pericarp membrane, are invaded by mycelium of the fungus and converted into loose aggregation of smut spores(teliospores). ➢ Significant reduction in tillering. ➢ Except awns all parts of ear converted into smut spore. ➢ Black powder in ear-covered by slivery membrane. ➢ Membrane burst later & smut spore release. ➢ Group of smut spore called sorus. ➢ High respiration and low dry weight. Causal agent: Etiology Pathogen - Ustilago nuda tritici. (Syn. U. segetum var. tritici) Systematic position: Kingdom: Fungi Phylum: Basidiomycota Sub phylum: Ustilaginomycotina Class: Ustilaginomycetes Order: Ustilaginales Family: Ustilaginaceae Genus: Ustilago Species: U tritici (Pers.) Pathogen characters: ➢ It is an internally seed borne fungal disease. ➢ It causes systemic infection. ➢ The teliospores of the fungus are pale, olive brown, spherical to oval in shape, about 5-9 micro diameter and are adorned with minute echinulations on the wall. -

Iodiversity of Australian Smut Fungi

Fungal Diversity iodiversity of Australian smut fungi R.G. Shivas'* and K. Vanky2 'Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Plant Pathology Herbarium, 80 Meiers Road, Indooroopilly, Queensland 4068, Australia 2 Herbarium Ustilaginales Vanky, Gabriel-Biel-Str. 5, D-72076 Tiibingen, Germany Shivas, R.G. and Vanky, K. (2003). Biodiversity of Australian smut fungi. Fungal Diversity 13 :137-152. There are about 250 species of smut fungi known from Australia of which 95 are endemic. Fourteen of these endemic species were first collected in the period culminating with the publication of Daniel McAlpine's revision of Australian smut fungi in 1910. Of the 68 species treated by McAlpine, 10 were considered to be endemic to Australia at that time. Only 23 of the species treated by McAlpine have names that are currently accepted. During the following eighty years until 1990, a further 31 endemic species were collected and just 11 of these were named and described in that period. Since 1990, 50 further species of endemic smut fungi have been collected and named in Australia. There are 115 species that are restricted to either Australia or to Australia and the neighbouring countries of Indonesia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines . These 115 endemic species occur in 24 genera, namely Anthracoidea (1 species), Bauerago (1), Cintractia (3), Dermatosorus (1), Entyloma (3), Farysporium (1), Fulvisporium (1), Heterotolyposporium (1), Lundquistia (1), Macalpinomyces (4), Microbotryum (2), Moreaua (20), Pseudotracya (1), Restiosporium (5), Sporisorium (26), Thecaphora (2), Tilletia (12), Tolyposporella (1), Tranzscheliella (1), Urocystis (2), Ustanciosporium (1), Ustilago (22), Websdanea (1) and Yelsemia (2). About a half of these local and regional endemic species occur on grasses and a quarter on sedges. -

Comparative Analysis of the Maize Smut Fungi Ustilago Maydis and Sporisorium Reilianum

Comparative Analysis of the Maize Smut Fungi Ustilago maydis and Sporisorium reilianum Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) dem Fachbereich Biologie der Philipps-Universität Marburg vorgelegt von Bernadette Heinze aus Johannesburg Marburg / Lahn 2009 Vom Fachbereich Biologie der Philipps-Universität Marburg als Dissertation angenommen am: Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Regine Kahmann Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Bölker Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Die Untersuchungen zur vorliegenden Arbeit wurden von März 2003 bis April 2007 am Max-Planck-Institut für Terrestrische Mikrobiologie in der Abteilung Organismische Interaktionen unter Betreuung von Dr. Jan Schirawski durchgeführt. Teile dieser Arbeit sind veröffentlicht in : Schirawski J, Heinze B, Wagenknecht M, Kahmann R . 2005. Mating type loci of Sporisorium reilianum : Novel pattern with three a and multiple b specificities. Eukaryotic Cell 4:1317-27 Reinecke G, Heinze B, Schirawski J, Büttner H, Kahmann R and Basse C . 2008. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis and its relevance for increased IAA levels in infected tissue and host tumour formation. Molecular Plant Pathology 9(3): 339-355. Erklärung Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich meine Dissertation mit dem Titel ”Comparative analysis of the maize smut fungi Ustilago maydis and Sporisorium reilianum “ selbständig, ohne unerlaubte Hilfe angefertigt und mich dabei keiner anderen als der von mir ausdrücklich bezeichneten Quellen und Hilfen bedient habe. Diese Dissertation wurde in der jetzigen oder einer ähnlichen Form noch bei keiner anderen Hochschule eingereicht und hat noch keinen sonstigen Prüfungszwecken gedient. Ort, Datum Bernadette Heinze In memory of my fathers Jerry Goodman and Christian Heinze. “Every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life are based on the labors of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the same measure as I have received and am still receiving. -

The Smuts of Wheat, Oats, Barley

360 YEARBOOK OF AGRICULTURE 1953 consist of chlor otic spots and streaks. The virus is transmitted by at least two species of leafhoppcrs, Nephoiettix apicalis (hipunctatus) var. cincticeps and Deltocephalus dor salis. Experiments with N. apicalis have shown that the virus The Smuts of passes through part of the eggs to the next generation, for as many as seven generations. Wheat, Oats, H. H. McKiNNEY holds degrees from Michigan State College and the University Barley of Wisconsin. In igig he joined the staff of the division of cereal crops and diseases of the Bureau of Plant Industry^ Soils, and C. S. Holton, V. F. Tapke Agricultural Engineering, where he has devoted most of his lim.e in research on Many millions of dollars' worth of viruses and virus diseases. grain are destroyed every year by the smuts of wheat, oats, and barley. For further reading: For purposes of study and control, //. H. McKinney: Evidence of Virus Muta- we can consider the smuts as being tion in the Common Mosaic of Tobcicco, seedling-infecting or floral-infecting. Journal of Agricultural Research, volume 5/, The seedling-infecting species come pages g^i-gSi, 1^33; Mosaic Diseases of Wheat and Related Cereals, U. S. D. A. Circular ^42, in contact with the host plants as ig37; Mosaic of Bromus inermis, Knih H. follows: The microscopic spores from Fellows and C. 0. Johnston, Phytopaihology, smutted plants are carried by wind, volume j2, page 331, ig42; Genera of the Plant rain, insects, and other agencies to Viruses, Journal oj the Washington Academy oj Sciences, volume 34, pages I3g-i54, 1944; De- the heads of healthy plants (as in scriptions and Revision of Several Species of loose smut of oats). -

Loose Smut and Common Bunt of Wheat Stephen N

® ® KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIKUQBKPFLK KPQFQRQBLCDOF@RIQROB>KA>QRO>IBPLRO@BP KLTELT KLTKLT G1978 Loose Smut and Common Bunt of Wheat Stephen N. Wegulo, Extension Plant Pathologist loss from loose smut is usually minimal (about 1 percent or Loose smut and common bunt are fungal diseases less). However, the disease can cause losses as high as 25 common to wheat in Nebraska. Planting resistant cul- percent or more in severe cases. In general, percent yield loss tivars and fungicide-treated seed will help with control from loose smut is approximately equal to the percentage of and management. affected wheat heads. Common bunt reduces both grain quality and yield. Grain contaminated by bunt spores has a darkened appearance and a Cause and Occurrence fishy, pungent smell. The smell is due to an organic compound, trimethylamine, which in appropriate concentrations can The smut diseases of wheat that occur in Nebraska are cause explosions in combines during harvest or in elevators loose smut (Figure 1) and common bunt (stinking smut, during storage. Contaminated grain usually is discounted at Figure 2). Loose smut is caused by the fungus Ustilago the elevator and can be rejected altogether. It cannot be used tritici and common bunt is caused by the fungi Tilletia tritici as feed because the strong order causes livestock to reject it. and T. laevis. Both diseases can occur anywhere in the state However, it may be used in ethanol production. where wheat is grown and are noticeable from heading to harvest. Rye, triticale, and some grasses also can be affected Disease Symptoms by both diseases.