Analysis and Discussion of Selected Vocal Motets of Anton Bruckner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

Linz Simonystraße Bussteig 1 Gültig Ab: 21.04.2019 2 0 17.22 S 400 Steyr City Point 0 18.33

Départ/Departure Aktuelle Abfahrt Abfahrten Linz Simonystraße Bussteig 1 gültig ab: 21.04.2019 2 0 17.22 S 400 Steyr City Point 0 18.33 . Montag - Freitag 17.23 410 Sierning Busterminal 0 18.09 14.00 Linie Verlauf/Endhaltestelle an 0 17.41 410 Niederneukirchen Ortsmitte 0 18.06 14.03 409 Asten Ortsmitte 2 14.15 . 0 18.21 14.23 05.00 Linie Verlauf/Endhaltestelle an 17.46 611 Traun Hauptplatz (Neubauer Straße) ¶' Enns Dr.-Renner-Straße 17.52 401 Steyr City Point 0 19.07 Mauthausen Bahnhof (Vorplatz) 14.34 0 06.15 05.06 400 Steyr City Point 0 0 2 . 14.46 611 Traun Hauptplatz (Neubauer Straße) 15.21 . 18.00 Linie Verlauf/Endhaltestelle an 0 16.00 06.00 Linie Verlauf/Endhaltestelle an 14.52 401 Steyr City Point 18.07 611 Haid Busterminal (Hauptplatz) 0 18.43 0 06.03 409 Asten Ortsmitte 2 06.15 . 18.11 410 Sierning Busterminal 0 19.00 15.00 Linie Verlauf/Endhaltestelle an ¶' Enns Dr.-Renner-Straße 06.23 18.22 S 400 Enns Hauptplatz (Stadtturm) 0 18.49 15.42 S 410 Sierning Busterminal 0 16.23 Mauthausen Bahnhof (Vorplatz) 06.34 18.41 411 Hofkirchen i.Tkr. Ortsmitte 0 19.17 15.42 F 410 Sierning Busterminal 0 16.23 06.12 412 Hofkirchen i.Tkr. Ortsmitte 0 06.35 18.46 611 Traun Hauptplatz (Neubauer Straße) 0 19.21 õ 06.12 S 401 Steyr City Point 0 07.21 18.52 401 Steyr City Point 0 20.05 15.46 611 Traun Hauptplatz (Neubauer Straße) 0 16.21 06.12 F 401 Steyr City Point 0 07.25 0 0 0 07.30 . -

Neukonzeption Wirtschaftförderung Und Stadtmarketing Heilbronn

CIMA Beratung + Management GmbH Kaufkraftstrom- und Einzelhandelsstrukturanalyse Oberösterreich-Niederbayern Detailpräsentation für den Bezirk Linz Land Stadtentwicklung M a r k e t i n g Regionalwirtschaft Einzelhandel Wirtschaftsförderung Citymanagement I m m o b i l i e n Präsentation am 09. Februar 2015 Ing. Mag. Georg Gumpinger Organisationsberatung K u l t u r T o u r i s m u s I Studien-Rahmenbedingungen 2 Kerninhalte und zeitlicher Ablauf . Kerninhalte der Studie Kaufkraftstromanalyse in OÖ, Niederbayern sowie allen angrenzenden Räumen Branchenmixanalyse in 89 „zentralen“ oö. und 20 niederbayerischen Standorten Beurteilung der städtebaulichen, verkehrsinfrastrukturellen und wirtschaftlichen Innenstadtrahmenbedingungen in 38 oö. und 13 bayerischen Städten Entwicklung eines Simulationsmodells zur zukünftigen Erstbeurteilung von Einzelhandelsgroßprojekte . Bearbeitungszeit November 2013 bis Oktober 2014 . „zentrale“ Untersuchungsstandorte im Bezirk Ansfelden Neuhofen an der Krems Asten Pasching Enns St. Florian Hörsching Traun Leonding 3 Unterschiede zu bisherigen OÖ weiten Untersuchungen Projektbausteine Oberösterreich niederbayerische Grenzlandkreise angrenzende Räume Kaufkraftstrom- 13.860 Interviews 3.310 Interviews 630 Interviews in analyse Südböhmen davon 1.150 830 Interviews in im Bezirk Linz Land Nieder- und Oberbayern Branchenmix- 7.048 Handelsbetriebe 2.683 Handelsbetriebe keine Erhebungen analyse davon 660 im Bezirk Linz Land City-Qualitätscheck 38 „zentrale“ 13„zentrale“ keine Erhebungen Handelsstandorte -

I N F O R M a T I O N

I N F O R M A T I O N zur Pressekonferenz mit Markus ACHLEITNER Wirtschafts-Landesrat zum Thema Landesrat Achleitner on Tour – im Gespräch im Bezirk Linz-Land Dienstag, 29. Jänner 2019 Restaurant Cubus, AEC, 4040 Linz www.markus-achleitner.at LR Achleitner 2 Auf Tour durch alle Bezirke Oberösterreichs Vergangene Woche startete Wirtschafts-Landesrat seine Tour durch alle oberösterreichischen Bezirke und verbrachte jeweils einen Tag in den Bezirken Kirchdorf und Ried im Innkreis. „Nach den ersten Wochen in meiner neuer Funktion ist es mir wichtig, in die Regionen zu kommen, mir selbst ein Bild zu machen und aus erster Hand im Gespräch mit den Menschen zu erfahren, was die Anliegen und Wünsche an das Zukunftsressort sind“, erklärt Wirtschafts-Landesrat Markus Achleitner. Im Mittelpunkt der Bezirkstage steht dabei naturgemäß der Kontakt mit den Unternehmerinnen und Unternehmer im Bezirk. Deshalb startete der heutige Tag mit einem Business-Frühstück mit den Vertreterinnen und Vertretern der Wirtschaft im Bezirk Linz-Land. Darüber hinaus am Programm stehen Besuche mit Firmenbesichtigungen in den Unternehmen TRUMPF Maschinen Austria in Pasching und bei Rosenbauer International AG in Leonding. Im Rahmen des Besuchs bei Rosenbauer International AG wird auch ein Gespräch mit den Vertreterinnen und Vertreter der Industrie im Bezirk stattfinden. Bis April wird Wirtschafts-Landesrat Markus Achleitner alle Bezirke besuchen. „Politik findet nicht hinter dem Schreibtisch statt, sondern im Gespräch mit den Menschen und dafür werde ich mir in den nächsten Monaten noch ausgiebiger als sonst Zeit nehmen“, betont Wirtschafts- Landesrat Achleitner. Pressekonferenz am 29. Jänner 2019 LR Achleitner 3 Aktuelle wirtschaftliche Situation und aktuelle Projekte im Bezirk Linz-Land Arbeitsmarkt Die Situation des Arbeitsmarktes in Oberösterreich zeigt sich aktuell grundsätzlich sehr erfreulich. -

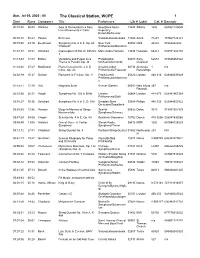

5, 2020 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Jul 05, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 05:50 Watkins Soul of Remembrance from New Black Music 13225 Albany 1200 034061120025 Five Movements in Color Repertory Ensemble/Dunner 00:08:3505:43 Paulus Berceuse Yolanda Kondonassis 11483 Azica 71281 787867128121 00:15:4844:19 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 New York 08852 CBS 42222 07464422222 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Bernstein 01:01:37 10:51 Schubert Impromptu in B flat, D. 935 No. Marc-Andre Hamelin 13496 Hyperion 68213 034571282138 3 01:13:4317:49 Britten Variations and Fugue on a Philadelphia 04033 Sony 62638 074646263822 Theme of Purcell, Op. 34 Orchestra/Ormandy Classical 01:33:02 27:47 MacDowell Piano Concerto No. 2 in D Amato/London 00734 Archduke 1 n/a minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Freeman Recordings 02:02:1910:37 Dvorak Romance in F minor, Op. 11 Frank/Czech 05323 London 460 316 028946031629 Philharmonic/Mackerra s 02:14:1117:25 Dett Magnolia Suite Denver Oldham 05092 New World 367 n/a Records 02:33:0626:51 Haydn Symphony No. 102 in B flat London 00664 London 414 673 028941467324 Philharmonic/Solti 03:01:2730:36 Schubert Symphony No. 6 in C, D. 589 Dresden State 03988 Philips 446 539 028944653922 Orchestra/Sawallisch 03:33:3312:36 Hanson Elegy in Memory of Serge Seattle 00825 Delos 3073 013491307329 Koussevitsky Symphony/Schwarz 03:47:2409:55 Chopin Scherzo No. 4 in E, Op. 54 Benjamin Grosvenor 10752 Decca 478 3206 028947832065 03:58:49 13:08 Harbach One of Ours - A Cather Slovak Radio 08416 MSR 1252 681585125229 Symphony Symphony/Trevor 04:13:1227:41 Chadwick String Quartet No. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2018 This

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2018 This is the fifteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2017-November 2018). The 130 selections have come from 25 members of the team and 70 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources - I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, 8 have received two nominations: Mahler and Strauss with Sergiu Celibidache on the Munich Phil choral music by Pavel Chesnokov on Reference Recordings Shostakovich symphonies with Andris Nelsons on DG The Gluepot Connection from the Londinium Choir on Somm The John Adams Edition on the Berlin Phil’s own label Historic recordings of Carlo Zecchi on APR Pärt symphonies on ECM works for two pianos by Stravinsky on Hyperion Chandos was this year’s leading label with 11 nominations, significantly more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2400 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year the choice was a little easier than usual. Pavel CHESNOKOV Teach Me Thy Statutes - PaTRAM Institute Male Choir/Vladimir Gorbik rec. 2016 REFERENCE RECORDINGS FR-727 SACD The most significant anniversary of 2018 was that of the centenary of the death of Claude Debussy, and while there were fine recordings of his music, none stood as deserving of this accolade as much as the choral works of Pavel Chesnokov. -

M1928 1945–1950

M1928 RECORDS OF THE GERMAN EXTERNAL ASSETS BRANCH OF THE U.S. ALLIED COMMISSION FOR AUSTRIA (USACA) SECTION, 1945–1950 Matthew Olsen prepared the Introduction and arranged these records for microfilming. National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC 2003 INTRODUCTION On the 132 rolls of this microfilm publication, M1928, are reproduced reports on businesses with German affiliations and information on the organization and operations of the German External Assets Branch of the United States Element, Allied Commission for Austria (USACA) Section, 1945–1950. These records are part of the Records of United States Occupation Headquarters, World War II, Record Group (RG) 260. Background The U.S. Allied Commission for Austria (USACA) Section was responsible for civil affairs and military government administration in the American section (U.S. Zone) of occupied Austria, including the U.S. sector of Vienna. USACA Section constituted the U.S. Element of the Allied Commission for Austria. The four-power occupation administration was established by a U.S., British, French, and Soviet agreement signed July 4, 1945. It was organized concurrently with the establishment of Headquarters, United States Forces Austria (HQ USFA) on July 5, 1945, as a component of the U.S. Forces, European Theater (USFET). The single position of USFA Commanding General and U.S. High Commissioner for Austria was held by Gen. Mark Clark from July 5, 1945, to May 16, 1947, and by Lt. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes from May 17, 1947, to September 19, 1950. USACA Section was abolished following transfer of the U.S. occupation government from military to civilian authority. -

2. Kammerkonzert „HAYDNS ENTDECKER“ Eine Hommage an Den Komponisten Johann Georg Reutter So 13

Generalmusikdirektor Axel Kober PROGRAMM 2. Kammerkonzert „HAYDNS ENTDECKER“ Eine Hommage an den Komponisten Johann Georg Reutter So 13. Oktober 2019, 19.00 Uhr Philharmonie Mercatorhalle Hana Blažíková Sopran Barockensemble nuovo aspetto Ermöglicht durch Kulturpartner Gefördert vom Duisburger Kammerkonzerte Johann Georg Reutter Sonntag, 13. Oktober 2019, 19.00 Uhr „Soletto al mio caro“, Arie aus „Alcide trasformato in dio“ Philharmonie Mercatorhalle für Sopran, Salterio und Basso continuo (1729) Giuseppe Porsile Andante aus „Il giorno felice“ (1723) Hana Blažíková Sopran Francesco Bartolomeo Conti (1681-1732) „Dei colli nostri", nuovo aspetto: Arie aus „Il trionfo dell’amicizia e dell’amore“ für Sopran, Christian Binde Horn Mandoline, Harfe, Baryton und Basso continuo (1711) Jörg Schultess Horn Helena Zemanová Violine Pause Frauke Pöhl Violine Corina Golomoz Viola Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) / Henri Compan Elisabeth Seitz Salterio „Je ne vous disais point: j’aime“ Johanna Seitz Harfe aus „Le Fat dupé“ für Sopran und Harfe Michael Dücker Laute, Mandolino Ulrike Becker Violoncello, Barytono Johann Georg Reutter „Dura legge a chi t’adora“, Arie aus „Archidamia“ Francesco Savignano Wiener Bass für Sopran, Salterio, Laute und Basso continuo (1727) Luca Quintavalle Cembalo Joseph Haydn Aus: Sinfonie C-Dur „Le Distrait“ Hob. I:60 Programm in der Kammermusikfassung für Harfe, Violine, Viola und Bass von Meingosus Gaelle (1774/1809) Adagio – Finale Johann Georg Reutter (1708-1772) „Dal nostro nuovo aspetto“, „The Inspired Bard“ Hob. XXXIb:25 aus -

Grosser Saal Klangwolke Brucknerhaus Präsentiert Von Der Linz Ag Linz

ZWISCHEN CREDO Vollendeter Genuss TRADITION BEKENNTNIS braucht ein & GLAUBE perfektes MODERNE Zusammenspiel RELIGION Als führendes Energie- und Infrastrukturunternehmen im oberösterreichischen Zentralraum sind wir ein starker Partner für Wirtschaft, Kunst und Kultur und die Menschen in der Region. Die LINZ AG wünscht allen Besucherinnen und Besuchern beste Unterhaltung. bezahlte Anzeige LINZ AG_Brucknerfest 190x245.indd 1 02.05.18 10:32 6 Vorworte 12 Saison 2018/19 16 Abos 2018/19 22 Das Große Abonnement 32 Sonntagsmatineen 44 Internationale Orchester 50 Bruckner Orchester Linz 56 Kost-Proben 60 Das besondere Konzert 66 Oratorien 128 Hier & Jetzt 72 Chorkonzerte 134 Moderierte Foyer-Konzerte INHALTS- 78 Liederabende 138 Musikalischer Adventkalender 84 Streichquartette 146 BrucknerBeats 90 Kammermusik 150 Russische Dienstage 96 Stars von morgen 154 Musik der Völker 102 Klavierrecitals 160 Jazz VERZEICHNIS 108 Orgelkonzerte 168 Jazzbrunch 114 Orgelmusik zur Teatime 172 Gemischter Satz 118 WortKlang 176 Kinder.Jugend 124 Ars Antiqua Austria 196 Serenaden 204 Kooperationen 216 Kalendarium 236 Saalpläne 242 Karten & Service 4 5 Linz hat sich schon längst als interessanter heimischen, aber auch internationalen Künst- Der Veröffentlichung des neuen Saisonpro- Musik wird heutzutage bevorzugt über diverse und innovativer Kulturstandort auch auf in- lerinnen und Künstlern es ermöglichen, ihr gramms des Brucknerhauses Linz sehen Medien, vom Radio bis zum Internet, gehört. ternationaler Ebene Anerkennung verschafft. Potenzial abzurufen und sich zu entfalten. Für unzählige Kulturinteressierte jedes Jahr er- Dennoch hat die klassische Form des Konzerts Ein wichtiger Meilenstein auf diesem Weg war alle Kulturinteressierten jeglichen Alters bietet wartungsvoll entgegen. Heuer dürfte die nichts von ihrer Attraktivität eingebüßt. Denn bislang auf jeden Fall die Errichtung des Bruck- das ausgewogene und abwechslungsreiche Spannung besonders groß sein, weil es die das Live-Erlebnis bleibt einzigartig – dank der nerhauses Linz. -

Vida De Anton Bruckner

CICLO BRUCKNER ENERO 1996 Fundación Juan March CICLO BRUCKNER ENERO 1996 ÍNDICE Pág. Presentación 3 Cronología básica 5 Programa general 7 Introducción general, por Angel-Fernando Mayo 11 Notas al programa: Primer concierto 17 Segundo concierto 21 Textos de las obras cantadas 25 Tercer concierto 31 Participantes 35 Antón Bruckner es hoy uno de los sinfonistas más prestigiosos del siglo XIX. Ya son páginas de historia de la música su ferviente admiración por Wagnery las diatribas que Hanslicky los partidarios de Brahms mantuvieron entonces respecto a su arte sinfónico, y un capítulo importante de la historia de la difusión musical lo ocupa la lenta recepción de su obra hasta el triunfo incuestionable de los últimos años. Pero Bruckner es también autor de un buen número de obras corales, con o sin acompañamiento de órgano, y de muy pocas pero significativas obras de cámara. También escribió para órgano -aunque siempre añoraremos más y más ambiciosas obras en quien fue organista profesional-, algo para piano y muy pocas canciones. En este ciclo, que no puede acercarse al mundo sinfónico, hemos acogido la mayor parte de su obra camerística centrándola en su importante Quinteto para cuerda, y una buena antología de su obra coral, desde la temprana Misa para el Jueves Santo de 1844 hasta ejemplos de su estilo final en 1885, en la época de su explosión sinfónica. Más de cuarenta años de actividad musical que ayudará al buen aficionado a completar la imagen de uno de los músicos más importantes del posromanticismo. Para no dejar aislado el Cuarteto de cuerda de 1862, hemos programado uno de los de su colega y contrincante Brahms. -

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers by Bwaar Omer

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers By Bwaar Omer Germany is known as a land of poets and thinkers and has been the origin of many great composers and artists. In the early 1920s, the country was becoming a hub for artists and new music. In the time of the Weimar Republic during the roaring twenties, jazz music was a symbol of the time and it was used to represent the acceptance of the newly introduced cultures. Many conservatives, however, opposed this rise of for- eign culture and new music. Guido Fackler, a German scientist, contends this became a more apparent issue when Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) took power in 1933 and created the Third Reich. The forbidden music during the Third Reich, known as degen- erative music, was deemed to be anti-German and people who listened to it were not considered true Germans by nationalists. A famous composer who was negatively affected by the brand of degenerative music was Kurt Weill (1900-1950). Weill was a Jewish composer and playwright who was using his com- positions and stories in order to expose the Nazi agenda and criticize society for not foreseeing the perils to come (Hinton par. 11). Weill was exiled from Germany when the Nazi party took power and he went to America to continue his career. While Weill was exiled from Germany and lacked power to fight back, the Nazis created propaganda to attack any type of music associated with Jews and blacks. The “Entartete Musik” poster portrays a cartoon of a black individual playing a saxo- phone whose lips have been enlarged in an attempt to make him look more like an animal rather than a human. -

J Präsidenten Des Nationalrates Dr

4208/AB XVIII. GP - Anfragebeantwortung (gescanntes Original) 1 von 10 C" 11- q~'44 der Beilagen zu den Stenographischen Protokollen des Nationalrates XVIII. Gesetzgebungsperiode DR. FRANZ LOSCHNAK BUNDESMINISTER FOR INNERES L/2c€ IAB r Zahl: 42.999/tO-IV/6/93 199~ ... f'!k.. 01. An den zu 41ff2 ~J Präsidenten des Nationalrates Dr. Heinz FISCHER Parlament t017 Wien Wien, am 1. April 1993 Die Abgeordneten zum Nationalrat Dr. PARTIK-PABLE und Genossen haben am 1. März 1993 unter der Nummer 4393/J an mich eine schriftliche parlamentarische Anfrage betreffend "Unregelmäßigkeiten bei der Durchführung des Volksbegehrens 'Österreich zuerst'" gerichtet, die folgenden Wortlaut hat: "1. Ist Ihnen o.a. Vorfall bekannt? 2. Wieviele Unterschriften auf den Eintragungslisten des Volksbegehrens "Österreich zuerst" wurden aus welchen Gründen für ungültig erklärt? Es wird um genaue Auf gliederung nach Bezirken und Einti'agungslokalen, sowie den· Gründen ftir die U ngül• tigerklärung ersucht. 3. Aus o.a. Zeitungsartikel läßt sich weiters entnehmen, daß es einen Erlaß des Bundes ministeriums für Inneres gibt, wonach für die Gültigkeit der Eintragung auch die Unterschrift lesbar sein muß. a) Gibt es einen solchen Erlaß? b) Wenn ja, wie ist der gen aue Wortlaut dieses Erlasses? 4. Warum wurden österreichischen Bürgerinnen und Bürgern, die ihre Unterschrift leisteten, nicht mitgeteilt, daß nur eine leserliche Unterschrift gültig ist? www.parlament.gv.at 2 von 10 4208/AB XVIII. GP - Anfragebeantwortung (gescanntes Original) - 2- 5. Aus o.a. läßt sich schließen, daß Beamte den im Gesetz nonnierten und von ihnen durch Erlaß in Erinnerung gerufenen Bestimmungen der Manuduktionspflicht nicht nachgekommen sind. Werden Sie gegen die involvierten Beamten dienstrechtliche Schritte veranlassen? a) Wenn ja, welche Maßnahmen werden Sie setzen? b) Wenn nein, warum nicht? 6.