45 Minutes from Doom! Tony Blair and the Radical Bible Rebranded." Harnessing Chaos: the Bible in English Political Discourse Since 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring Business Forum Programme

Join us in March for a series of events with our Frontbench politicians including Keir Starmer, Anneliese Dodds, Ed Miliband, Bridget Phillipson, Rachel Reeves, Emily Thornberry, Chi Onwurah, Lucy Powell, Pat McFadden, Jim McMahon and many others. Monday 8 march 2021 8am – 8.50am Breakfast Anneliese Dodds ‘In Conversation with’ Helia Ebrahimi, Ch4 Economics correspondent, and audience Q and A Supported by The City of London Corporation with introductory video from Catherine McGuinness 9am - 10.30am Breakout roundtables: Three choices of topics lasting 30 minutes each Theme: Economic recovery: Building an economy for the future 1. Lucy Powell – Industrial policy after Covid 2. Bridget Phillipson, James Murray – The future of business economic support 3. Ed Miliband, Matt Pennycook – Green economic recovery 4. Pat McFadden, Abena Oppong-Asare – What kind of recovery? 5. Emily Thornberry, Bill Esterson – Boosting British business overseas 6. Kate Green, Toby Perkins – Building skills for a post Covid economy 10:30 - 11.00am Break 11.00 - 12.00pm Panel discussion An Inclusive Economic Recovery panel, with Anneliese Dodds Chair: Claire Bennison, Head of ACCA UK Anneliese Dodds, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer Mary-Ann Stephenson, Director of the Women’s Budget Group Miatta Fahnbulleh, Chief Executive of the New Economics Foundation Rachel Bleetman, ACCA Policy and Research Manager Rain Newton-Smith, Chief Economist, CBI Supported by ACCA 14245_21 Reproduced from electronic media, promoted by David Evans, General Secretary, the Labour Party, -

From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies Sara Krausert

The University of Chicago Law School Roundtable Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-1998 From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies Sara Krausert Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/roundtable Recommended Citation Krausert, Sara (1998) "From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies," The University of Chicago Law School Roundtable: Vol. 5: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/roundtable/vol5/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Roundtable by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies SARA KRAUSERT t The paradigmatic First Lady' embodies the traditional role played by women in the United States. Since the position's creation, both Presidents and the public have wanted First Ladies to be seen and not heard. Some First Ladies have stayed within these confines, either by doing no more than simply supporting their husbands, or by taking care to exercise power only behind the scenes. Several First Ladies in this century, however have followed the lead of Eleanor Roosevelt, who broke barriers in her vigorous campaigns for various social causes, and they have brought many worthy issues to the forefront of the American consciousness.' Most recently, with the rumblings of discontent with the role's limited opportunities for independent action that accompanied the arrival of the women's movement, Rosalynn Carter and Hillary Clinton attempted to expand the role of the First Lady even further by becoming policy-makers during their husbands' presidencies.3 This evolution in the office of First Lady parallels women's general progress in society. -

For the Curious Mind. Be Part of It

For the curious mind. Be part of it. ProsPect – good writing about the things that matter Prospect breaks the mould of modern-day journalism. it covers a broad range of topics from current affairs to culture and business to science and technology. every month Prospect combines elegant design with a strikingly original mix of essays, opinion, debate and reviews. What sets it apart is its intellectual depth. Each issue brings together the sharpest minds to unravel the complexities of events and ideas that define the modern world. Politically, Prospect is neither left nor right. Its views are those of its opinionated mix of editors and contributors who write for an audience keen to participate in the debate, but who will ultimately make up their own mind. The result is an entertaining, informative and open minded magazine that mixes compelling argument and clear headed analysis with an international style. ❝Prospect offers intellectual discovery when everything else is going in the opposite direction.❞ david goodhart, editor, prospect. our editorial Prospect is britain’s foremost monthly commentary on current affairs, epitomising long-form journalism at its best. Features Nothing is off limits to our feature writers. What is certain is that this section combines breadth of coverage with thoughtful, unpredictable and eclectic comment. This is in-depth reading at its best – probing to awaken the curious mind. opinions Thought provoking, often intellectual, always surprising, these articles are written by leading thinkers and opinion formers. science and technology things to do this month The story behind the headlines, across a Our pick of what to see and do this month – mix of subjects, from hard sciences through from the popular to the obscure, this new section consumer technology and media. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

The Latest Version of the PM - Brown with Added Blair

The latest version of the PM - Brown with added Blair Suddenly, all the major political leaders are sounding like ardent Blairites. Even the man previously known as the Anti-Blair Andrew Rawnsley The Observer, Sunday February 10. 2008 One of our most senior politicians - to spare his blushes, let's call him Mr X - went to his doctor recently complaining of severe stomach pains. The GP sent him off to one of London's better regarded hospitals for an endoscopy. I've not had the pleasure myself, but those who have endured this procedure tell me that it is not the nicest way to spend your day, having a flexible tube with a camera on its snout stuck down your throat or up your rectum. Unless you are a masochist, it is certainly not a procedure you would want to repeat more times than you absolutely had to. Mr X waited some weeks for his appointment. He then had to wait some further weeks to hear from the hospital. When he made inquiries, the hospital told him that - whoops - it had lost his results. This confronted him with the choice of going back on the waiting list for another endoscopy or making other arrangements. He made - and who can blame him? - other arrangements. You could say that this is a story with a satisfyingly egalitarian moral. The NHS can be as hopeless when it is treating a very important person as it can be when it is dealing with an ordinary patient. But it leaves me alarmed. If a hospital can be so careless with a very well- known Member of Parliament, it is likely to be sloppier still when it comes to the average voter who does not have the same opportunities to raise his or her voice in protest. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

An Archive of Media References to the Cameron Personal Narrative, And

An archive of media references to the Cameron personal narrative and his repositioning of the Conservative party in his first 100 days as Conservative Party leader. (km, 12.4.06 version) David Cameron, it is very widely agreed, is repositioning/rebranding the Conservative Party, i. e. presenting a changed identity of it to the UK electorate. He is doing this in the light of where the Tories’ political competition is in terms of policy and personality. Also doing it because the Tories lost power in 1997 and have failed in two general elections to win it back. Below are 17 media references which are offered as instances of the rebranding exercise. Those references are interpreted by category afterwards. The term ‘branding’ has its origins in marketing for products, and from there it migrated to the promotion of corporate bodies in business, public and voluntary sectors. If this note was written in 1997, ‘repositioning’ would have been used to describe the process in hand, but now it has an outdated air in the face of the continuous intrusion of market behaviour into all aspects of public life. References 11.12.05 – The Observer, p. 19, carries a page entitled the ‘The Cameron Phenomenon’ with pics showing the new leader on his bike; buying milk; tieless on a bridge with an environmentalist. Cameron was elected party leader on December 6. The headline for the accompanying article by Ned Temko is ‘Within minutes of victory Cameron’s camp set in motion a tightly organised timetable’ 1.1.06 – The national papers carry a page advert from the Conservatives headlined ‘The world is changing . -

One East Midlands MP Guide 2014

One East Midlands MP Guide 2014 One East Midlands MP Guide 2014 1 One East Midlands MP Guide 2014 Contents Introduction Introduction 2 Following the success of our first three annual MP Guides in 2011, 2012 and 2013, this guide contains MPs by Party & Constituency 3-25 updated information on all 46 MPs covering the East Conservative 3-18 Midlands following the May 2010 general election. Labour 18-25 The guide is organised by political party and then Index by Name 26 arranged alphabetically by constituency. You will also find useful indexes by name and constituency at Index by Constituency 27 the back of the guide. All information is update as of May 2014. For each MP you will find details of their political party, constituency and contact details (at Westminister and their constituency). Where available, you will also find details of their current position within parliament, their departmental contact details, the select committees that they are a member of, their broader political interests, their departmental contact details, website and Twitter feed. For further information on individual MPs visit www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/mps . For further information on One East Midlands visit www.oneeastmidlands.org.uk . 2 One East Midlands MP Guide 2014 Nigel Mills MP Mark Simmonds MP Constituency: Amber Valley Constituency: Boston & Skegness Party: Conservative Party: Conservative Contact details (Westminster): Contact details (Westminster): House of Commons, London SW1A House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA 0AA Tel: 020 7219 7233 Tel: -

Championing the Talent and Potential of Women Leaders in Law

Championing the talent and potential of women leaders in law Championing the talent and potential of women leaders in law 1 Women Who Will 2020 Contents Contents & Methodology 2 Introduction 3 Foreword 4 Women in law: a snapshot 6 10 Women Who Will - in-house 8 10 Women Who Will - in private practice 13 10 Women Who Will - change makers 17 Women leaders in law: a call to action 20 About the Next 100 Years project 24 The Inspirational Women Awards at a glance 25 References 27 METHODOLOGY In compiling this report the teams at Obelisk Support and Next Hundred Years invited nominations from senior General Counsel and other senior leaders in law, as well as including women recognised by the judges of the First Hundred Years/Next Hundred Years Inspirational Women Awards and doing our own research across published and social media. Space only permits us to shout out 30 brilliant women in this report. We know there are many, many more Women Who Will out there, and we hope this prompts greater recognition of all the talented women across the legal industry. 2 Women Who Will 2020 INTRODUCTION A letter from Dana Denis- Smith, our CEO Back in 2019, as we celebrated 100 years of women being able to practise law in England & Wales, my team and I had the idea of inviting legal leaders in the FTSE 100 to champion some of the talented women they work with. As well as shining a light on talented individuals, we also wanted to reflect on the gender diversity of leadership in law forces with the Next 100 Years project and their and why it matters. -

May Day PROG 2014

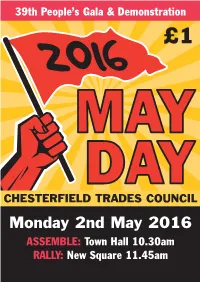

39th People’s Gala & Demonstration £1 CHESTERFIELD TRADES COUNCIL Monday 2nd May 2016 ASSEMBLE: Town Hall 10.30am RALLY: New Square 11.45am DEMONSTRATION Assemble at CHESTERFIELD TOWN HALL at 10.30am March Off at 11.00am (See inside of back cover for route) RALLY NEW SQUARE: 11.45am Speakers: Tosh McDonald President Amalgamated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen Jane Loftus President Communications Workers Union Toby Perkins MP for Chesterfield Raya Ziyaei Refugee Solidarity Campaigner MAY DAY at a GLANCE 9.00am - 4.00pm Stalls and Entertainment in New Square 10.30am March Assembles 10.45am Jill Brunt will address the marchers from the Town Hall Steps on “Women, Austerity and Pension Poverty” 11.00am March Off 11.45am Rally & Speeches in New Square 1.00pm Sheffield Socialist Choir in Market Hall Assembly Rooms 12.30pm - 4.00pm Live Entertainment in New Square (page 18-19) 12.30pm Faith and Branko 1.40pm Bikini Beach Band 2.50pm Bleeding Hearts “Folk-Punk for Punk-Folk” 2 Contents Page Welcome to Chesterfield’s 2015 May Day Event 4 - 5 Tosh McDonald 6 - 8 Jane Loftus 9 - 11 Raya Ziyaei 12 - 13 Toby Perkins 14 - 15 South Yorkshire Freedom Riders 16 - 17 FREE Concert in New Square 18 - 19 A Cooperative Manifesto for Chesterfield - a work in progress 20 - 21 Chesterfield’s other anti-war MP 22 - 24 International Solidarity in the Great Miners' Strike 25 - 26 Unite in Sports Direct - Shirebrook Project 28 - 29 Derbyshire Asbestos Support Team’s Panel Solicitors 31 Shock deaths amongst former Staveley Chemical workers 32 Asbestos: The hidden threat in many school buildings 33 May Day Route 35 The People’s Anthems 36 Chesterfield May Day Gala would like to thank Ruane Transport of Chesterfield for the use of their trailer in New Square. -

Literaturliste

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Sommersemester 2007 Institut für Politische Wissenschaft und Soziologie Hauptseminar für den Magister-Studiengang: Tony Blair und New Labour. Was bleibt? Dr. Brigitte Seebacher Literaturliste Signatur Titel A 06-07035 Astle, Julian (Ed.): Britain after Blair : a Liberal agenda. London 2006 POL 500 GROS Beck Becker, Bernd: Politik in Großbritannien. Paderborn 2002 X 08480/2001, 5 Suppl. Bischoff, Joachim / Lieber, Christoph: Epochenbegriff. „Soziale Gerechtigkeit“. Hamburg 2001 A 98-00618 Blair, Tony: Meine Vision. London 1997 A 05-04584 Coates, David: Prolonged labour : the slow birth of New Labour in Britain. Basingstoke 2005 A 06-03088 Coughlin, Con: American Ally. Tony Blair and the War on Terror. London 2006 A 00-04093 Dixon, Keith: Ein würdiger Erbe. Anthony Blair und der Thatcherismus. Konstanz 2000 C 06-00792 Haworth, Alan / Hayter, Dianne: Men Who Made Labour. 2006 A 06-07010 Hennessy, Peter: The prime minister. The office and its holders since 1945. London 2001 POL 500 GROS Hüb Hübner, Emil: Das politische System Großbritannien. Eine Einführung. 1999 [im Bestand nur die Auflage von 1998] A 06-07017 Jenkins, Simon: Thatcher & Sons: A Revolution in Three Acts. London 2006 A 06-00968 Kandel, Johannes: Der Nordirland Konflikt. Bonn 2005 POL 900 GROS Kaste Kastendiek, H / Sturm, R: (Hrsg): Länderbericht Großbritannien, Bonn 2006 (3. Aktualisierte und neu bearbeitete Auflage der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. POL 500 GROS Krumm Krumm, Thomas/ Noetzel, Thomas: Das Regierungssystem Großbritanniens. Eine Einführung. München 2006. POL 500 GROS Leach Leach, Robert/ u.a.: British politics. Basingstoke 2006 A 05-04568 Leonard, Dick: A century of premiers. Salisbury to Blair. -

Cultura Inglesa Proficiency Test Version: Test A

CULTURA INGLESA PROFICIENCY TEST VERSION: TEST A PAPER - Reading TEMPO: 2h00min INSTRUÇÃO AOS CANDIDATOS Só abra este caderno quando o fiscal autorizar. Escreva seu nome e data de da prova abaixo. Leia as instruções para cada parte corretamente. É permitido o uso de dicionário físico. Responda a prova à caneta. HÁ 2 QUESTÕES NESSA PROVA Student: ____________________________________________ Date: _____________ Teacher: ____________________________________________ Grade: ____________ 1 Reading – Text A Questions 1 - 6 Marque a resposta correta de acordo com o texto abaixo. The Politician, The Wife, The Citizen, and her Newspaper Rethinking women, democracy, and media(ted) representation Charlotte Adcock Introduction Our understanding of the problems of “real” women cannot lie outside the “imagined” constructs in and through which “women” emerge as subjects. (Rajeswari Sunder Rajan 1993, p. 10) On May 8, 1997, Britain's New Labour party chose to celebrate its first day in government by staging a photocall of its female MPs gathered around the new Prime Minister, Tony Blair. This image of a record number of 120 women elected to Westminster was initially widely interpreted as a fitting symbol of Labour's modernisation and commitment to a new, inclusive style of representative politics. In contrast to a Conservative Party many regarded as incompetent, sleazy or out-of-touch, these women appeared to embody a new political force. May 1997, declared one commentator, “promised the dawn of a new era in gender relations” (Wilkinson 1998, p. 58). “Blair's got a huge ‘girl power’ boost,” proclaimed The Sun newspaper, while The Guardian described the doubling of women in the House of Commons as an “irreversible trend” in the “slipstream” of the larger electoral revolution that “transforms absolutely every possibility on the political landscape.”1 “At the heart of this new Britain,” the Mirror's Woman page predicted, “will be the issues that affect women: child care, health and education.