S T a T E P # 0 L I C E RESEARCH REPORT RESEARCH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Kidder, Jefferson Parish Collection

ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 949 East Second Street Library and Archives Tucson, AZ 85719 (520) 617-1157 [email protected] MS 406 KIDDER, JEFFERSON PARISH, 1875-1908 PAPERS, 1902-1972 DESCRIPTION Jeff Kidder was a member of the Arizona Rangers from 1904 until he was killed by Mexican police in 1908. Most of this collection consists of material from the period shortly before and after his death on April 5, 1908: his daily diary from 1907, letters to Kidder, his letters to his mother and letters of condolence to his mother following his death. The collection also includes his enlistment and discharge papers from the Rangers, “Wanted” posters from 1907, newspaper clippings from the time of his shooting and several newspaper and magazine articles retelling the legend of the shooting of Sgt. Kidder. One box, .5 linear foot BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Jefferson Parish Kidder, Arizona Ranger, was born in Vermilion, South Dakota, on November 5,1875. He was named after his grandfather who was a judge and an active politician in Vermont, Minnesota and the Dakotas. Jeff graduated from high school in Vermilion and then headed West. About the same time his parents moved to San Jacinto, California. After a time in Montana, Jeff ended up in Bisbee where he was associated with the Arizona Copper Company. He enlisted in the Arizona Rangers in April of 1903. Most of his time with the Rangers was spent patrolling the Arizona/Mexico border where he had the reputation of being “Hell on smugglers.” Kidder was also reported to be a very quick hand with a six-shooter. -

The Posse Comitatus and the Office of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned to the Aid of Law Enforcement

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 104 Article 3 Issue 4 Symposium On Guns In America Fall 2015 The oP sse Comitatus And The Office Of Sheriff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement David B. Kopel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation David B. Kopel, The Posse Comitatus And The Office Of erSh iff: Armed Citizens Summoned To The Aid Of Law Enforcement, 104 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 761 (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol104/iss4/3 This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/15/10404-0761 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 104, No. 4 Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. THE POSSE COMITATUS AND THE OFFICE OF SHERIFF: ARMED CITIZENS SUMMONED TO THE AID OF LAW ENFORCEMENT DAVID B. KOPEL* Posse comitatus is the legal power of sheriffs and other officials to summon armed citizens to aid in keeping the peace. The posse comitatus can be traced back at least as far as the reign of Alfred the Great in ninth- century England. The institution thrives today in the United States; a study of Colorado finds many county sheriffs have active posses. Like the law of the posse comitatus, the law of the office of sheriff has been remarkably stable for over a millennium. -

Tombstone Arizona's History and Information Journal

Tombstone Arizona’s History and Information Journal - September 2014 - Vol. 12 - Issue 09 - ISSN 1942-096X Interesting historical tidbits of news and information from the Town Too Tough to die. Tombstone Epitpah - December 15, 1927 “Oh! Oh! What a Night ‘Twas Says A. H. Gardner, Tombstone, Ariz. That Night Before Christmas “The evening’s entertainment began with a knockout. Johnny Walker – John W. Walker, you understand, then federal court reporter and fresh from Chicago – and I were just about putting the finishing touches to a roast mallard duck supper at the old Kreuder Café on Allen Street when Kreuder met one of his customers at the cashier’s counter and laid him cold with an uppercut that would have at that time done credit to even hard hitting bog Fitzsimmons. There were no frills to the affair. Kreuder just waited until his man came down the aisle, gave one glance at the check he handed to the cashier, and then applied a clenched fist to the point of his customer’s jaw. All was over but the shouting. “The proceedings struck me as not only being odd but as being carried out in a rather cold-blooded, businesslike manner. Being just from New York City, one might think that such an occurrence would have little effect on me. But I had never seen anything in which Kreuder laid low the man which 5 his establishment had just feasted. “Oh, yes! I did forget to tell you why Kreuder took a punch at his customer. It was this way. “I supposed the customer got some peculiar notion that a 50 per cent discount should be made on all T-bone steak dinners which he ate at Kreuder’s for every time a check for 50 cents was handed to him, he erased the ‘0,’ put a ‘2’ in front of the ‘5’ and then put the ‘cents’ mark – ‘c’ – after the ‘25.’ It seemed that the cashier became suspicious, told Kreuder CORNER OF 5TH & ALLEN STREETS about it, and according to the customs of old Tombstone of a quarter-century ago, the customer ‘had it coming to him.’ Forthwith Kreuder was duly bound to see that ‘it’ arrived in true western style. -

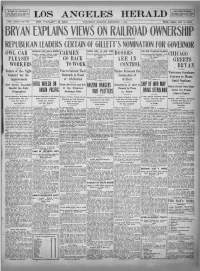

Bryanexplains Views on Railroad Ownership

TIMK ISMONEY AnyKRTisrcn s Vnn will have mor# <lm« tat Who rnnnnt Mffnttt to n«» <tlapl*.T• o«li<T IhlniriIf you rn(ru.l more n<tv«rM«tne nhnnlrt huff \u25a0 •»«»< of your InnUn to lltrnM n<H. Los Angeles Herald. nrt la The llrrxlfl. II will p*y. i) XXXIII, n l VOL. NO. 340. PRICE: | "&r*s,<£ff"{'6s CENTS WEDNESDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 5, 1906. PRICE: SINGLE COPY 6, CENTS BRYAN EXPLAINS VIEWS ON RAILROAD OWNERSHIP BRYAN EXPLAINS VIEWS ON RAILROAD OWNERSHIP BURGLAR TRAP KILLS WOMAN SCORE HURT IN NEW YORK FOR NEW FLOATING PALACES OWL CAR Seattle Landlady Opens Lodger's Ferry Car Strikes Van and Passengers BOSSES Hamburg.American Steamship Conic Trunk and Receives Fatal Bui- CARMEN Are Jumbled To- pany Adds Five Millions to CHICAGO let, Dying Instantly i aether Its Capital By Associated Press. By Associated Press. By Awoelated Press. PLEASES SEATTLE, Wash., Sept. 4.—Mrs. GO BACK NEW YORK, Sept. 4.—Six men were IN HAMBURG, Sept. 4.— The Hamburg- Daly, proprietress of Induing bndly In the ABE Steamship company toduy Emma a so hurt an accident on American Avenue, Thirty-ninth street of plan GEEETS house at 582H First In thl9 ferry line the announced a to lseue $5,000,000 now city, was shot and Instantly killed this Brooklyn Ilapld Transit .that they were capital, making a total of $30,000,000. afternoon by a burglar trap arranged taken to the Coney Island reception The official statement explains that WORKERS In his trunk by one of her lodgers, Gene TOWORK hospital. -

ARIZONA RANGERS COLLECTION MS 1063 Collection, 1901-1909, 1958-1970 (Bulk 1958-1970)

ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 949 East Second Street Library and Archives Tucson, AZ 85719 (520) 617-1157 Fax: (520) 628-5695 [email protected] ARIZONA RANGERS COLLECTION MS 1063 Collection, 1901-1909, 1958-1970 (bulk 1958-1970) DESCRIPTION The bulk of the collection consists of minutes of meetings and correspondence between the various Ranger groups in Arizona from 1958 to 1970. Although these are not official records of the organization they do provide valuable information and background. Also included are photocopies of by-laws and reports from the original Arizona Rangers which were in existence from 1901 to 1910. 5 Boxes, 2.5 linear feet. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE The Arizona Rangers were organized in 1901 to combat the organized banditry growing in the territory. The Rangers were reorganized in 1957 to assist state and local law enforcement agencies and provide community service when needed. Stuart Copeland was the Historian for the Arizona Rangers when the group was reorganized in 1957. He compiled copies of historical materials for the earlier Rangers as well as maintained the historical records of the group reorganized in 1957. ACQUISITION This collection was donated to the Arizona Historical Society by Carol Dingel on November 29, 1993. ACCESS There are no restrictions on this collection. COPYRIGHT Requests for permission to publish materials from this collection should be addressed to the Arizona Historical Society. PROCESSING This collection was processed in April 1995 by Brian Beattie, under the supervision of Archivists Jerry Kyle and Rose Byrne. The collection was consolidated in May 1997 by William Tackenberg under the supervision of Archivist Rose Byrne. -

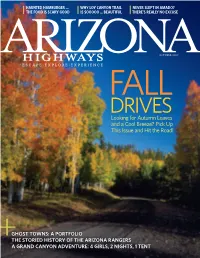

DRIVES Looking for Autumn Leaves and a Cool Breeze? Pick up This Issue and Hit the Road!

HAUNTED HAMBURGER ... WHY LOY CANYON TRAIL NEVER SLEPT IN AMADO? THE FOOD IS SCARY GOOD IS SOOOOO ... BEAUTIFUL THERE’S REALLY NO EXCUSE OCTOBER 2009 ESCAPE. EXPLORE. EXPERIENCE FALL DRIVES Looking for Autumn Leaves and a Cool Breeze? Pick Up This Issue and Hit the Road! GHOST TOWNS: A PORTFOLIO + THE STORIED HISTORY OF THE ARIZONA RANGERS A GRAND CANYON ADVENTURE: 4 GIRLS, 2 NIGHTS, 1 TENT features departments contents Grand Canyon 14 FALL DRIVES 2 EDITOR’S LETTER 3 CONTRIBUTORS 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR National Park It doesn’t matter where you’re from, autumn is special. 5 THE JOURNAL Flagstaff 10.09 Even people in Vermont get excited about fall color. People, places and things from around the state, including Oatman Jerome We’re no different in Arizona. The weather is beautiful. an old-time prospector who’s still hoping to strike it rich, White Mountains a hamburger joint in Jerome that’s loaded with spirit — The leaves are more beautiful. And the combination Stanton or spirits — and the best place to shack up in Amado. Superstition Mountains adds up to a perfect scenic drive, whether you hop in a PHOENIX Pinaleño Mountains car or hop on a bike. Either way, this story will steer you 44 SCENIC DRIVE Castle Dome Tucson in the right direction. EDITED BY KELLY KRAMER Box Canyon Road: About four months ago, a lightning fire touched this scenic drive. Turns out, it was just Box Canyon Chiricahua Mountains 24 TOWN SPIRIT Mother Nature working her magic. Amado Gleeson Ghost towns are pretty common in Arizona. -

Arizona Historical Review, Vol

Arizona Historical Review, Vol. 5 No. 4 (January 1933) Item Type text; Article Publisher Arizona State Historian (Phoenix, AZ) Journal Arizona Historical Review Rights This content is in the public domain. Download date 05/10/2021 17:04:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623331 THE ARIZONA HISTORICAL REVIEW Vol. V. JANUARY, 1933 No. 4 CONTENTS The Autobiography of George Wiley Paul Hunt 253 As Told by GEORGE WILEY PAUL HUNT to SIDNEY KARTUS Phoenix—A History of Its Pioneer Days and People 264 By JAMES M. BARNEY Arizona Place Names 286 By WILL C. BARNES A Description of Sonora in 1772 302 By ALFRED BARNABY THOMAS Kino of Pimeria Alta (Continued) _308 BY RUFUS KAY WYLLYS Pioneers: 1854 to 1864 (Continued) 327 BY FRANK C. LOCKWOOD Some Unpublished History of the Southwest (Continued) 333 BY COL. CORNELIUS C. SMITH Book Reviews _341 Arizona Pioneers Historical Society 345 Arizona Museum Notes 346 Published Quarterly by the ARIZONA STATE HISTORIAN By Authority of the State Historian EFFIE R. KEEN SIDNEY KARTUS Editor Managing Editor Associate Editors Contributing Editor RUFUS K. WYLLYS MRS. GEO. F. KITT WILL C. BARNES EFFIE R. KEEN, STATE HISTORIAN The publication is not responsible for opinions expressed by contributors. Subscription $3.00 a year. Single copies $1.00 Entered as second class matter at the Postoffice at Phoenix, Arizona, under Act of Congress, October 3, 1917, Sec. 395. PUBLICATIONS FOR SALE HISTORY OF ARIZONA, by Thomas Edwin Parish, in eight vol- umes. Vols. VII and VIII are out of Print. Vols. I and II, $1.50 each; V and VI $5.00 each; and a few copies without covers of III and IV, reading matter intact, $3.00 each. -

HISTORY of MORENCI, ARIZONA by Roberta Watt a Thesis Submitted To

History of Morenci, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Watt, Roberta, 1918- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 10:41:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/338164 HISTORY OF MORENCI, ARIZONA by Roberta Watt A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of \ MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona AHOSIHA tIDHS?OI T5»T8IH S$bW s&i9doR 8±89ffT A n± r; ?0 % C H M 9 maec E979/ /9s0> 7 6 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major depart ment or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

A Look Back at the History of the Arizona Department of Public Safety

50 YEARS OF VIGILANCE A LOOK BACK AT THE HISTORY OF THE ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY (602) 223-2000 | azdps.gov 2102 West Encanto Boulevard Phoenix, AZ 85009 50th ANNIVERSARY EDITION 3 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR You are about to embark on a journey through history. Take a ride with us, “Down the Highways”, as we celebrate 50 years of the Arizona Department of Public Safety. The Digest, an internal publication of AZDPS, has been in circulation for over 60 years, highlighting stories of employees and the Department. The following stories are excerpts directly taken from a Digest publication in that respective year with some years omitted. Over the last 50 years, there have been many agency changing events but there have also been lull years, which is common for any large organizations, especially governmental. Creative Services Unit 4 VANTAGE POINT COL. FRANK MILSTEAD We, the Arizona Department of Public Safety, are made of history and, today, we are the makers of history. It is an indescribable feeling of honor being the director of the Department during its 50th anniversary. This is an incredible, venerable organization with a storied past. A past full of highs and lows, miracles and tragedies, excitement and lulls. Many changes have occurred in the last four years of my administration and in the Department’s 50 years, but one thing that has not changed is the amazing personnel that make up AZDPS - past, present, and future. Life is funny and unpredictable. In 1988, a time capsule was buried under the flagpoles of the Headquarters Building in Phoenix with an unearthing scheduled in 2019. -

Civil Action No. 13-CV-1300-MSK-MJW JOHN B

Case 1:13-cv-01300-MSK-MJW Document 70 Filed 08/22/13 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 50 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Civil Action No. 13-CV-1300-MSK-MJW JOHN B. COOKE, Sheriff of Weld County, Colorado; et al. Plaintiffs, vs. JOHN W. HICKENLOOPER, Governor of the State of Colorado, Defendant. FIFTY-FIVE COLORADO SHERIFFS’ RESPONSE BRIEF TO DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS THEM IN THEIR OFFICIAL CAPACITIES Fifty-five Colorado Sheriffs, by and through their counsel, file this Response Brief to Defendant’s motion to dismiss them from the case in their official capacities.1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT Under the Tenth Circuit’s precedents on the political subdivision doctrine, the 55 Sheriffs have standing because they have “a personal stake” in the case. As will be described below, the personal stake includes the apprehension of criminals who have murdered a Sheriff. This did happen in 1994, and if HB 1224 had been in effect then, the murderers could have escaped. 1 For the reasons set forth in the separate Response filed by the other Plaintiffs, which the 55 Sheriffs also join, this Court should deny Defendant’s motion to dismiss the second, third, and fourth claims for relief. 1 Case 1:13-cv-01300-MSK-MJW Document 70 Filed 08/22/13 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 50 The Sheriffs also have a personal stake in HB 1229, which makes every Sheriff into a criminal simply for conducting the ordinary operations of his or her Office by temporarily transferring firearms to deputies. -

A Comprehensive History of the West Virginia State Police, 1919-1979 By

A Comprehensive History of the West Virginia State Police, 1919-1979 by Merle T. Cole (Copyright, Merle T. Cole, 1998) Among state police departments [the West Virginia State Police] may, with its long and arduous experience, be regarded as a battle scarred veteran. It helped develop a new era of policing in the United States. Only three surviving departments preceded it. None faced greater obstacles. None have contributed more to the safety and well-being of the citizens whose lives and property it protects or to the strength and development of democracy within a state.--Col. H. Clare Hess, Superintendent, Department of Public Safety (West Virginia State Police) Twelfth Biennial Report (1940- 1942) NEW INTRODUCTION (1998) This is a minor rewrite of my original monograph, "Sixty Years of Service: A History of the West Virginia State Police, 1919-1979" (Copyright, 1979). I want to thank Sergeant Ric Robinson, Director of Media Relations, West Virginia State Police, for his support in the electronic publication of this study. -Merle T. Cole ORIGINAL INTRODUCTION (1979) This is a history of the origins and development of the West Virginia State Police (WVSP), the fourth oldest state police agency in America, now entering its 60th year of public service. My interest in the WVSP reached an early peak while I was a political science student at Marshall University. At the time, I could only manage to produce a limited study in the form of a term paper. Time and opportunity being more abundant recently, I have been able to complete a long-felt desire by producing this monograph.