Opening Doors: Unlocking Housing Supply for Affordability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginning of a Sacred and Culturally Safe Healing Journey

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE **TRIGGER WARNING** This news release contains information about Indian Residential Schools. Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh Nations Announce Investigation at Former St. Paul’s Indian Residential School Site Beginning of a sacred and culturally safe healing journey Coast Salish Territories | August 10, 2021 — Today, the Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation) announced it has embarked on an Indigenous-led initiative, on behalf of its people and in partnership with its relatives, the xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm (Musqueam) and səl̓ilw̓ ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, to find answers about the children who attended the former St. Paul’s Indian Residential School but never made it home. Over 2,000 Indigenous children, representing six generations of Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh, xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm, and səl̓ilw̓ ətaʔɬ Nations, and other Indigenous communities, were institutionalized at St. Paul’s from grades one through eight. Many of these same children were then forcibly relocated to Kamloops Indian Residential School, where the remains of at least 215 children were confirmed this May. Oral histories told by St. Paul’s survivors include stories about children who disappeared. According to public records, 12 unidentified students died while attending St. Paul’s between 1904 and 1913. The Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh Úxwumixw’s goal with the investigation of the former residential school site, located within Squamish unceded territory, is to find the location of each of these children and bring them home to rest. “It’s important to note that our People’s experiences with St. Paul’s Indian Residential School are well known and healing is needed to move forward. This work is being done to respect and address both known and unknown knowledge, and is a critical part of reconciliation,” says Khelsilem, spokesperson for the Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh Úxwumixw. -

First Nations, Catholics Work at North Vancouver Residential School Site

First Nations, Catholics work at North Vancouver residential school site NORTH VANCOUVER, British Columbia (CNS) — Three First Nations are working with the Archdiocese of Vancouver to look for remains of at least 12 students who attended the former St. Paul’s Indian Residential School. The investigation is complicated because it is roughly where the parking lot sits at St. Thomas Aquinas Regional Secondary School in North Vancouver. “Our intention here today is to begin a healing process for our survivors and for our people, for the survivors who attended St. Paul’s Indian Residential School, but also the intergenerational survivors who live with and have felt the effects of the residential school system,” said Squamish Nation spokesman Khelsilem, also known as Dustin Rivers. He announced Aug. 10 that the inquiry would begin in mid- August and would involve hearing personal accounts from survivors, collecting archival material about St. Paul’s, and a field search that could involve ground-penetrating radar or other technology. “We know based off of the current archival information that we have that there are a number of children that attended the school that did not make it home,” he said, “but most of the information is piecemeal.” A news release from the Squamish Nation said public records show 12 unidentified students died while at St. Paul’s between 1904 and 1913, but the location of their remains is unknown. Rivers said his hope is the investigation will bring to light truths about the residential school, which operated from 1899 to 1959, and the students who attended it. -

Broadcasting Live from Unceded Coast Salish Territory: Aboriginal Community Radio, Unsettling Vancouver

Broadcasting Live from Unceded Coast Salish Territory: Aboriginal Community Radio, Unsettling Vancouver Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Margaret Helen Bissler, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Christine Ballengee-Morris Danielle Fosler-Lussier Copyright by Margaret Helen Bissler 2014 Abstract This thesis examines moments of spatial, historical, and identity transformation through the performance of aboriginal community radio production in contemporary Vancouver, BC. It highlights points at which space is marked as indigenous and colonial through physical movement and through discourse. Beginning with a trip to record a public demonstration for later broadcast, this thesis follows the event in a public performance to question and unpack spatial, sonic, and historical references made by participants. The protest calls for present action while drawing upon past experiences of indigenous peoples locally and nationwide that affect the lived present and foreseeable future. This thesis also moves to position aboriginal community radio practice in a particular place and time, locating the discussion in unceded indigenous territory within the governmental forces of Canadian regulation at a single radio station. Vancouver Co- op Radio, to provide a more coherent microcosm of Vancouver's indigenous community radio scene. CFRO is located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and its shows, mostly aired live from the studio, broadcast a marginalized voices. The content of its overtly indigenous shows includes aboriginal language learning and revival, aboriginal political issues or “talk radio,” “NDN” (pronounced “Indian”) pop culture/music, and aboriginal music more broadly writ. -

Temstl'i7 Ta Snichm

Kwi Awt Stelmexw.com [email protected] PO Box 57145 East Hastings Vancouver, BC, V5K 5G6 TEMSTL’I7 TA SNICHM 2017-2018 Adult Immersion Program Follow these four steps to apply to the 2017-2018 Adult Immersion Program Step 1 Read the Program Guidelines for information about the purpose of the program, who should apply, program timeline, application assessment process and criteria, and other details. Step 2 Read the Important Information section. If you still have questions about the program or the application process, contact Kwi Awt Stelmexw as indicated below. Step 3 Study for and complete the Oral Admissions Exam (see Appendix B). Step 4 Complete all sections of the attached application form. Be sure to use the Checklist (Part E of the form) to confirm that you have completed all relevant sections of the form and have included all required support material. The purpose of Kwi Awt Stelmexw is to strengthen all aspects of Squamish heritage, language, culture, and art, and we welcome applications from all people, although priority selection will be given to applicants with Squamish ancestry. Deadline: Monday, February 13th, 2017 at 5pm. Your completed application form and all required support material must be received electronically or in-hand by the Department of First Nations Studies at Simon Fraser University by Monday, February 13th, 2017, at 5pm. Submit Applications To: Main Program Contact: Lorraine Yam, First Nations Studies Academic Advisor Khelsilem [email protected] 778-782-5595 Programming Director [email protected] Department of First Nations Studies 778-987-8809 Kwi Awt Stelmexw Simon Fraser University PO Box 57145 8888 University Drive, Saywell Hall 9091 East Hastings Street Burnaby, British Columbia Vancouver, B.C., V5K 5G6 Canada V5A 1S6 1 Kwi Awt Stelmexw.com [email protected] PO Box 57145 East Hastings Vancouver, BC, V5K 5G6 PROGRAM GUIDELINES Mandate of Kwi Awt Stelmexw is a registered non-profit based in Vancouver, British Columbia. -

The District of Squamish Government-To-Government Collaboration

Pathways to Collaboration SQUAMISH NATION - THE DISTRICT OF SQUAMISH GOVERNMENT-TO-GOVERNMENT COLLABORATION PATHWAY OVERVIEW The District of Squamish is located on the unceded territory of the Squamish Nation, whose territory stretches from North Vancouver to Gibson’s Landing to the north area of Howe Sound. Squamish Nation has seven reserves within the District of Squamish, and is a significant land owner within the District, with lands poised for economic development purposes and future member housing. In 2007, the District of Squamish and Squamish Nation formalized their commitments to a spirit of co-operation and government-to- government relationship by signing a Co-operation Protocol agreement. Based on the principles of co-operation outlined in the agreement, the Nation and the District established a working relationship that has allowed them to collaborate on several fronts. Today, the fruits of this collaborative relationship can be seen in an ongoing initiative to establish a jointly administered community forest. PATHWAY ACTIVITIES The collaborative pathway activities undertaken by the Squamish Nation and the District of Squamish included the following. $ $ Protocol and Joint Economic Communications Agreements Development Initiatives PROJECT OVERVIEW The District of Squamish and Squamish Nation have been forward in a relationship based on “trust, respect, and working together in a spirit of collaboration for many years mutual understanding.” Since the signing of the Co-operation now. In 2007, a Co-operation Protocol was signed with Protocol, the District of Squamish and Squamish Nation have the intention of establishing a government-to-government moved forward together on several collaborative initiatives. relationship. The purpose of the protocol was to formalize information sharing, improve communications, address The Squamish communities are nestled in a beautiful natural specific issues of mutual interest, and raise awareness and area enjoyed by a wide range of people. -

Culture|Shift: Blanketing

सं 啃 ति Kultura �رھ�گ 문화 šxʷtəhim̓ Culture Shift Blanketing the City in Arts & Culture Wa lhtim̓ á Vancouver Culture Plan 2020 - 2029 文化 حضارهCultura art & culture awaken provoke inspire inquire connect catalyze unsettle open clarify heal disrupt realize animate attune nourish dissolve reckon crystallize celebrate lead the way CULTURE|SHIFT CITY OF VANCOUVER 2 CULTURE|SHIFT CITY OF VANCOUVER Public Art Partnerships- Uninterrupted 20173 Unceded Lands of Musqueam, Squamish, & Tsleil-Waututh Culture|Shift is built upon the understanding and recognition that what is now known as Vancouver is located on the traditional, unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh (Squamish) and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, who have lived throughout this region for thousands of years. Their ancient continuity on these lands is reflected in their oral histories, arts and culture practices, and deep relationships with the lands and waters—and in the archaeological record. In this section, excerpts from the websites of each Nation are shared to affirm the importance of Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh visibility and voice in the work of building better relationships and futures on their lands. Musqueam Indian Band We are traditional hən̓ q̓ əmin̓ əm̓ speaking people… We have always moved throughout our territory using the resources it provides for fishing, hunting, trapping and gathering. We remain distinct and our cultural practices are strong, despite the devastating impacts of residential schools, colonial laws banning our ceremonies, and other attempts to assimilate our people. Our lands and waters continue to support our cultural and economic practices while serving as a source of knowledge and memory, encoded with our teachings and laws. -

Missionization and Sḵwxwú7mesh ̱ Political Economy, 1864-1923

Missionization and Sḵwxwú7mesẖ Political Economy, 1864-1923 by Sean Wilkinson B.A. (History & Economics), Simon Fraser University, 2009 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Wilkinson 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/) Approval Name: Sean Wilkinson Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title of Thesis: Missionization and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Political Economy, 1864-1923 Examining Committee: Chair: Jay Taylor, Professor Mary-Ellen Kelm Senior Supervisor Professor J.I. Little Co-Supervisor Professor Rudy Reimer/Yumḵs Internal Examiner Assistant Professor Date Defended/Approved: 17 January 2012 ii Abstract This thesis describes the relationship between Sḵwx̱wú7mesh-speaking people of present-day North Vancouver and the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in the period between 1864 and 1923. It presents the argument that the mission that the Oblates and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh mutually founded in the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh settlement of Eslhá7an (in present-day North Vancouver) was the most significant point of cultural contact between Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and non-native people during this period. Reading Sḵwx̱wú7mesh history during this period as primarily a story of responses to colonization, it argues that some of the most important Sḵwx̱wú7mesh political and diplomatic strategies, including external strategies of resistance and accommodation as well as internal strategies of political economy, were linked to trans-cultural experiences centred at Eslhá7an. It concludes by suggesting that the emergence of Sḵwx̱wú7mesh nationalism, culminating in the establishment of the modern Squamish Nation, may have been driven by these Eslhá7an-based political strategies. -

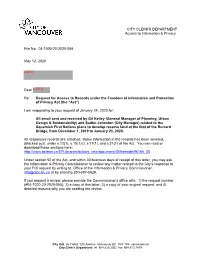

2020-065-Release.Pdf

CITY OF CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information & Privacy File No.: 04-1000-20-2020-065 May 12, 2020 s.22(1) Dear s.22(1) Re: -Request for Access to Records under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the “Act”) I am responding to your request of January 24, 2020 for: All email sent and received by Gil Kelley (General Manager of Planning, Urban Design & Sustainability) and Sadhu Johnston (City Manager) related to the Squamish First Nations plans to develop reserve land at the foot of the Burrard Bridge, from December 1, 2019 to January 23, 2020. All responsive records are attached. Some information in the records has been severed, (blacked out), under s.13(1), s.15(1)(l), s.17(1), and s.21(1) of the Act. You can read or download these sections here: http://www.bclaws.ca/EPLibraries/bclaws new/document/ID/freeside/96165 00 Under section 52 of the Act, and within 30 business days of receipt of this letter, you may ask the Information & Privacy Commissioner to review any matter related to the City’s response to your FOI request by writing to: Office of the Information & Privacy Commissioner, [email protected] or by phoning 250-387-5629. If you request a review, please provide the Commissioner’s office with: 1) the request number (#04-1000-20-2020-065); 2) a copy of this letter; 3) a copy of your original request; and 4) detailed reasons why you are seeking the review. City Hall 453 West 12th Avenue Vancouver BC V5Y 1V4 vancouver.ca City Clerk's Department tel: 604.829.2002 fax: 604.873.7419 Yours truly, Cobi Falconer, FOI Case Manager, for [Signature on file] Barbara J. -

Indigenous Relations Committee Agenda Package

METRO VANCOUVER REGIONAL DISTRICT INDIGENOUS RELATIONS COMMITTEE REGULAR MEETING Thursday, February 4, 2021 1:00 PM – 4:00 PM 28th Floor Committee Room, 4730 Kingsway, Burnaby, British Columbia and online via Zoom (log-in details provided) A G E N D A1 OPENING REMARKS Director Sav Dhaliwal, Board Chair 1. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA 1.1 February 4, 2021 Regular Meeting Agenda That the Indigenous Relations Committee adopt the agenda for its regular meeting scheduled for February 4, 2021 as circulated. 2. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES 2.1 October 8, 2020 Regular Meeting Minutes That the Indigenous Relations Committee adopt the minutes of its regular meeting held October 8, 2020 as circulated. 3. DELEGATIONS 4. INVITED PRESENTATIONS 5. REPORTS FROM COMMITTEE OR STAFF 5.1 2021 Indigenous Relations Committee Priorities and Work Plan That the Indigenous Relations Committee endorse the work plan as presented in the report dated January 20, 2021, titled “2021 Indigenous Relations Committee Priorities and Work Plan.” 1 Note: Recommendation is shown under each item, where applicable. January 22, 2021 43194761 Indigenous Relations Committee Indigenous Relations Committee Regular Agenda February 4, 2021 Agenda Page 2 of 3 5.2 Quarterly Report on Reconciliation Activities That the Indigenous Relations Committee receive for information the report dated January 8, 2021, titled “Quarterly Report on Reconciliation Activities.” 5.3 Metro Vancouver’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples That the MVRD Board receive for information the report dated January 22, 2021, titled “Metro Vancouver’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.” 5.4 Manager’s Report That the Indigenous Relations Committee receive for information the report dated January 14, 2021, titled “Manager’s Report.” 6. -

Climate Emergency Action Plan

REPORT Report Date: October 22, 2020 Contact: Matt Horne Contact No.: 604.673.8331 RTS No.: 13199 VanRIMS No.: 08-2000-20 Meeting Date: November 3, 2020 TO: Vancouver City Council FROM: General Manager of Planning, Urban Design and Sustainability and General Manager of Engineering Services SUBJECT: Climate Emergency Action Plan RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HOW WE MOVE To achieve the City’s complete, walkable neighbourhoods target (by 2030, 90% of people live within an easy walk/roll of their daily needs): A. THAT Council direct staff to report back on specific recommendations and actions on achieving the City’s complete, walkable neighbourhoods target through the Vancouver Plan. B. THAT Council direct staff to seek to exceed the City’s walkable neighbourhoods target in current planning initiatives, such as the Broadway Plan, and that Council adopt a sustainable transportation target of at least 80% of trips being made on foot, bike or transit by 2030 in current and emerging planning areas around rapid transit stations. To achieve the City’s sustainable transportation target (by 2030, two thirds of all trips in Vancouver will be made on foot, bike or transit): C. THAT Council direct staff to accelerate implementation of the Transportation 2040 directions. D. THAT Council direct staff to develop a Vancouver Transport Pricing Strategy and work toward implementation within the Metro Core by 2025 in accordance with Appendix A. Climate Emergency Action Plan – RTS 13199 2 E. THAT Council direct staff to develop 5-year (2021–25) active transportation and transit priority plans and begin to seek implementation in 2021 in accordance with Appendices B1–B4. -

![Indigenous People in North Vancouver Book]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6838/indigenous-people-in-north-vancouver-book-6646838.webp)

Indigenous People in North Vancouver Book]

North Vancouver Museum & Archives SCHOOL PROGRAMS 2017/18 Docent Script Secondary Indigenous Peoples in Education North Vancouver Book Guide Secondary Education Guide [INDIGENOUS PEOPLE IN NORTH VANCOUVER BOOK] Introduction/Background This education kit is based on the book Indigenous People and First Nations in North Vancouver: History, Traditions, and Culture written by Khelsilem, a Sk_wxmu7mesh-kwakwaka’wakw* writer and educator raised in North Vancouver. The book highlights significant aspects of the traditional and contemporary culture of Indigenous people and communities in North Vancouver. While acknowledging that many different groups and communities of Indigenous people travelled throughout, occupied, and gathered resources on the north shore of Burrard Inlet and surrounding areas, including the ancestors of the present-day Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, this book focuses on the recent contributions and histories of the Indigenous people who have communities on the north shore today. This book is part of the North Vancouver Museum and Archives series of “flipbooks,” large format, limited edition illustrated books, which provide easily accessible introductions to aspects of North Vancouver’s history. It also constitutes part of the NVMA travelling exhibit “Chief Dan George: Actor and Activist.” This book is an introduction to the rich histories, traditions, and culture of the Indigenous people in North Vancouver. It draws on archival documents and historic images from the NVMA and other institutions, and contemporary images and stories. Included in this kit is a detailed teacher’s package that provides instructors with lesson plan activities that guide students in the analysis of archival photographs. The lessons and activities were designed to complement BC’s social studies curriculum for grades 9 & 10, as well as the 2017 draft curriculum for the following grade 11 & 12 courses: BC First Peoples 11 and Contemporary Indigenous Studies 12. -

PROGRAM GUIDELINES 2017-2018 Adult Immersion Program

Kwi Awt Stelmexw.com [email protected] PO Box 57145 East Hastings Vancouver, BC, V5K 5G6 PROGRAM GUIDELINES 2017-2018 Adult Immersion Program Follow these four steps to apply to the 2017-2018 Adult Immersion Program Step 1 Read the Program Guidelines for information about the purpose of the program, who should apply, program timeline, application assessment process and criteria, and other details. Step 2 Read the Important Information section. If you still have questions about the program or the application process, contact Kwi Awt Stelmexw as indicated below. Step 3 Study for and complete the Oral Admissions Exam (see Appendix B). Step 4 Complete all sections of the attached application form. Be sure to use the Checklist (Part E of the form) to confirm that you have completed all relevant sections of the form and have included all required support material. The purpose of Kwi Awt Stelmexw is to strengthen all aspects of Squamish heritage, language, culture, and art, and we welcome applications from all people, although priority selection will be given to applicants with Squamish ancestry. Deadline: Monday, February 13th, 2017 at 12:00pm. Your completed application form and all required support material must be received electronically or in-hand by the Department of First Nations Studies at Simon Fraser University by Monday, February 13th, 2017, at 12:00pm SFU Contact: Main Program Contact: Lorraine Yam, Khelsilem First Nations Studies Academic Advisor Programming Director [email protected] [email protected] 778-782-5595 778-987-8809 Department of First Nations Studies Kwi Awt Stelmexw www.sfu.ca/fns/community PO Box 57145 East Hastings Street Simon Fraser University Vancouver, B.C., V5K 5G6 8888 University Drive, Saywell Hall 9091 Burnaby, British Columbia Canada V5A 1S6 1 Kwi Awt Stelmexw.com [email protected] PO Box 57145 East Hastings Vancouver, BC, V5K 5G6 Mandate of Kwi Awt Stelmexw is a registered non-profit based in Vancouver, British Organization Columbia.