Migration and Domestic Workers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everyone Loves E30s and This Triumvirate Must Rate As Three of The

040-048 BMWCAR 0314 07/02/2014 15:22 Page 40 Everyone loves E30s and this o finally the day has come where we can In the right corner the reigning world champion, measure up these legendary box-shaped the E30 M3, is painted in Lachs silver and weighs in triumvirate must rate as three beauties. This has to be one of the BMW (from new) at 1200kg and develops 200hp (140kW) showdowns of the century and who at 6750rpm and has a maximum torque of 177lb ft of the most desirable of the would have thought it would happen (238Nm) at 4750rpm. breed. The iconic M3 goes under African skies? Today is going to be a brawler; we are out in the In the left corner we have the two contenders, the west of the province of Gauteng approximately 40 head-to-head with the E30 333i and the E30 325iS Evolution. The 333i is kilometres outside of Johannesburg at the Delportan painted in Aero silver and weighs in at 1256kg. It Hill in Krugersdorp which has been a popular hillclimb South African-only 333i develops 197hp (145kW) at 5500rpm and has a venue since the ‘60s. We are in ‘Cradle’ country not and 325iS Evolution maximum torque of 210lb ft (285Nm) at 4300rpm. too far off from here are the Sterkfontein Caves – a The 325iS is painted in Ice white and weighs1147kg. World Heritage Site where ‘Mrs Ples’, a 2.1-million- Words: Johann Venter It develops 210hp (155kW) at 5920rpm, and has a year-old skull, and ‘Little Foot’, an almost complete Photography: Oliver Hirtenfelder maximum torque of 195lb ft (265Nm) at 4040rpm. -

Rooftop Solar PV Potential Assessment in the City of Johannesburg

Rooftop Solar PV Potential Assessment in the City of Johannesburg by Moroasereme Ntsoane Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sustainable Development in the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Alan Brent March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i | Page Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Cities are the modern era’s undisputed drivers for economic growth and development. But cities are also highly energy and resource intensive. Therefore, it is predictable that cities would be active participants in the global effort to creatively strike a balance between resources consumption and economic growth for a sustainable future. Part of this is exploiting the often neglected, but vital, solar photovoltaic (PV) resource and rooftop real estate within cities. At face value, a city with the real estate infrastructural sophistication of the City of Johannesburg (CoJ), presents an attractive opportunity for generating renewable energy from its building rooftops. However, the magnitude of this potential is yet to be fully characterised. Assessments of the rooftop solar PV potential of buildings in inner city locale are made complex by the variety of building typologies and rooftop accessibility. -

Budgeting for HIV/AIDS in South Africa: Report on Intergovernmental Funding Flows for an Integrated Response in the Social Sector

Budgeting for HIV/AIDS in South Africa: Report on intergovernmental funding flows for an integrated response in the social sector Alison Hickey Nhlanhla Ndlovu Teresa Guthrie AIDS Budget Unit November 2003 IDASA - Budget Information Service (BIS) 6 SPIN STREET • CHURCH SQUARE • CAPE TOWN 8001 PO BOX 1739 • CAPE TOWN 8000 • SOUTH AFRICA TEL + 27 (021) 467-5600 • FAX +27 (021) 462-0162 This Report is also available on-line at: www.idasa.org.za This research paper is jointly sponsored by the foreign development agencies of Australia (AusAID), the United Kingdom (DFID) and the United States (USAID) and admini stered by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies through a subcontract agreement with Nathan Associates Inc. © Budget Information Service, Idasa, 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The AIDS Budget Unit of the Budget Information Service, Idasa, would like to extend its gratitude to various people for their contribution towards the publication of this report. Firstly we would like to thank government officials who were able to take time off their very busy schedules to participate in our research advisory group and to offer us invaluable inputs and feedback on our research. Specifically we would like to thank Mrs Nomalanga Makwedini from the Eastern Cape, Dr Sandile Buthelezi from KwaZulu-Natal, Mrs Ntsiki Jolingana from the Free State, Dr Mark Blecher from National Treasury, Mr Gandi Moetlo from Limpopo, Dr Elizabeth Floyd from Gauteng, Dr Fareed Abdullah from the Western Cape and Mr Martin Hensher from the national Department of Health. We would also like to thank the following national government officials for making time to talk to us about HIV/AIDS budgets and expenditure issues: Gerritt Muller, Chief Director: Financial Management, national Department of Health; Johanna de Beer, Deputy Director: HIV/AIDS, national Department of Social Development; and Lungisa Fuzile, Chief Director: Provincial Policy and Planning, National Treasury. -

South African Climate Finance Landscape 2020

South African Climate Finance Landscape 2020 January 2021 AUTHORS Adila Cassim The GreenCape Sector Development Agency [email protected] Jack-Vincent Radmore The GreenCape Sector Development Agency [email protected] Natasha Dinham The Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship [email protected] Steve McCallum The Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Our analysis benefited from close dialogue and interaction about specific climate finance flows with a number of organisations and ministries active in areas relevant for this study, including, in alphabetical order: AIIM, BloombergNEF – BNEF, Carbon Trust, Climate and Development Knowledge Network, Climate Fund Managers, Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, Environmental Resources Management (ERM), FMO: Entrepreneurial Development Bank, FNB, Future growth (Old Mutual), Green Climate Fund, Inspired Evolution, International Finance Corporation, JHP Advisory, KfW Group, National Business Initiative, Nedbank, NESA Capital, Old Mutual, Old Mutual Alternatives, Prescient Capital, South African National Biodiversity Institute, South African National Treasury, Southern African Venture Capital and Private Equity Association, SouthSouthNorth, Standard Bank, The Department of Trade Industry and Competition, The Development Bank of Southern Africa, TIPS, United Farmer Fund. Experts in these organisations were critical in helping us better understand the available data, and our work has benefited -

Weekly Funding Opportunity Announcements Friday June 12, 2015

Weekly Funding Opportunity Announcements Friday June 12, 2015 NIH Funding Announcements – New This Week New RFA’s: Announcement Issuing Release Opening Date Expiration Activity Title Number Organization Date (SF424 Only) Date Code(s) NIDDK Centers for Diabetes RFA-DK-15-003 NIDDK 06-11-2015 10-23-2015 11-24-2015 P30 Translation ResearcH (P30) Novel or EnHanced Dental Restorative Materials for Class V RFA-DE-16-007 NIDCR 06-11-2015 08-29-2015 09-30-2015 R01 Lesions (R01) PartnersHips for tHe Development of Novel Assays to Predict Vaccine RFA-AI-15-033 NIAID 06-10-2015 08-30-2015 10-01-2015 R01 Efficacy (R01) Short Courses in HigH Priority Domains of BeHavioral and Social RFA-AG-16-010 NIA 06-09-2015 09-07-2015 10-08-2015 R25 Research on Aging (R25) Open Design Tools for SpeecH RFA-DC-16-002 NIDCD 06-08-2015 09-01-2015 10-02-2015 R43/R44 Signal Processing (R43/R44) Open Design Tools for SpeecH RFA-DC-16-001 NIDCD 06-08-2015 09-01-2015 10-02-2015 R01 Signal Processing (R01) Smoking Cessation witHin tHe Context of Lung Cancer Screening RFA-CA-15-011 NCI 06-05-2015 09-08-2015 10-09-2015 R01 (R01) Dimensional ApproacHes to Research Classification in RFA-MH-16-510 NIMH 06-05-2015 09-09-2015 10-10-2015 R01 PsycHiatric Disorders (R01) Prematurity-Related Ventilatory Control (Pre-Vent): Role in RFA-HL-16-015 NHLBI 06-05-2015 09-20-2015 10-21-2015 U01 Respiratory Outcomes Clinical Research Centers (CRC) (U01) 1 Prematurity-Related Ventilatory Control (Pre-Vent): Role in Respiratory Outcomes - LeadersHip RFA-HL-16-016 NHLBI 06-05-2015 09-20-2015 -

A Case Study of the Gauteng Freeway Improvement Project

MEGA PROJECT ANALYSIS: A CASE STUDY OF THE GAUTENG FREEWAY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT by Philip Parrock Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Political Science) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Janis van der Westhuizen March 2015 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (unless explicitly stated otherwise), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe and third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety, or in part, submitted it for obtaining any qualification Philip Parrock November 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Mega projects have fascinated human beings for as long as history can remember. The urge to build something bigger and better than has ever been done before has always been a driving force behind the human race’s relentless pursuit of technological advancement. It is in this vein that mega projects have evolved over time, as methods of construction improved, so did the scale on which people could attempt new projects. The Channel Tunnel between England and France, the Hoover Dam in America and the Millau Viaduct in the French countryside are some of the biggest examples of infrastructure projects in the world and these are all unequivocally, mega projects. Costing at least $ 250 million and incorporating major technological challenges, mega projects continue to inspire and motivate artists and engineers alike. -

Inception Report

The Municipal Area in Context The history of Mogale city is diverse with the towns of Krugersdorp and Magaliesburg being the most prominent in the development of the region. The old Krugersdorp, situated 33km west of Johannesburg, like most towns in the region had its origins in the discovery of gold on the 1. The spatial context of Mogale City Witwatersrand. On 26 April 1887 the government of Transvaal decided to buy 428 ha of the farm Perdekraal in order to establish an administrative centre for the mines that were developing on the rest of the farm. The owner of the farm insisted on the name Krugersdorp in 1.1 Regional context honour of the President of Transvaal, Paul Kruger. The first stands were sold on 31 October 1887 and two years after that the government donated 88 pound for the planting of trees along Mogale City lies directly west and south of the Johannesburg and Tshwane metropolitan areas the streets. The completion of a rail line from Johannesburg to Krugersdorp in 1891 brought respectively, and forms part of one of three district municipalities that make up the peripheral with it more development. In 1952 Krugersdorp became the first town in the world to produce areas of Gauteng province. To the north, west and south it borders onto Madibeng Local uranium as a by-product of gold. Municipality, Rustenburg Local Municipality and Randfontein Local Municipality respectively. Magaliesburg is situated on the southern slopes of the Magaliesberg. The mountain, valley and The West Rand District Management Area lies within the central-northern part of Mogale City, town are named after Mohale or Magali, the chief of the old Po-tribe. -

Property Information Locality Property Description Tenancy Property Images

CHAMDOR – JOHANNESBURG COMMERCIAL PROPERTY 7 ADCOCK STREET, CHAMDOR, KRUGERSDORP Property Information Locality Property Description Tenancy Property Images PROPERTY INFORMATION 7 ADCOCK STREET, CHAMDOR, KRUGERSDORP General Property Address Erf 198 7 Adcock Street, Chamdor, Krugersdorp Title Deed Information Title Deed Number T9569/2009 Registered Owners Geerlings Property Investment PTY (Ltd) Title Deed Description Portion 0 of Erf 198, Chamdor Ext. 1 Registered Extent 8568m² Extent of Improvements ± 2500m² Municipal Information Municipality Mogale City Local Municipality Zoning Commercial Monthly Property Rates R5 623.50 LOCALITY 7 ADCOCK STREET, CHAMDOR, KRUGERSDORP The subject property is situated in Adcock Street and is has a huge passing clientele which makes the property ideal for retail. Chamdor is one of six operational industrial nodes within the Mogale City Local Municipality and is located north-east of the town of Kagiso. The Chamdor industrial node is the largest industrial node in the Mogale City Local Municipality, comprising 259 Ha in extent. The Chamdor industrial node is located along a major movement spin (Chamdor Road / R558), connecting the node with the R41 moving in an east-west direction. The R558 connects Chamdor with Soweto to the south; and Krugersdorp to the north. The R41 links Chamdor with the City of Johannesburg to the south, and Randfontein to the west, serving as an important provincial movement spine. Latitude & Longitude for the site: -26.162033/27.804643 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 7 ADCOCK STREET, CHAMDOR, -

Toll Tariffs 2021

TOLL TARIFFS 2021 EFFECTIVE FROM 1 MARCH 2021 TOLL TARIFFS AND DISCOUNTS APPLICABLE TO THE CONVENTIONAL TOLL PLAZA, EFFECTIVE 01 MARCH 2021 Do note that this booklet is an explanatory document and does not replace the Government Gazette No. 44145, No. 44146, No. 44147, No. 44148 and No. 44149 on adjusted toll tariffs as published on 11 February 2021. PLAZA CLASS 1 CLASS 2 CLASS 3 CLASS 4 N1 HUGUENOT Mainline R42.50 R118.00 R185.00 R300.00 VAAL Mainline R71.50 R135.00 R162.00 R216.00 GRASMERE Mainline R21.50 R64.00 R75.00 R99.00 Ramp (N) R11.00 R32.00 R38.00 R49.00 Ramp (S) R11.00 R32.00 R38.00 R49.00 VERKEERDEVLEI Mainline R61.50 R123.00 R185.00 R260.00 STORMVOËL Ramp R10.00 R25.00 R29.00 R35.00 ZAMBESI Ramp R12.00 R30.00 R35.00 R42.00 PUMULANI Mainline R13.00 R32.00 R37.00 R45.00 WALLMANSTHAL Ramp R6.00 R15.00 R18.00 R20.50 MURRAYHILL Ramp R12.00 R30.00 R36.00 R41.00 HAMMANSKRAAL Ramp R28.00 R95.00 R103.00 R119.00 CAROUSEL Mainline R60.00 R160.00 R177.00 R204.00 MAUBANE Ramp R26.00 R69.00 R77.00 R89.00 KRANSKOP Mainline R48.50 R123.00 R165.00 R202.00 Ramp R13.50 R36.00 R42.00 R63.00 NYL Mainline R62.50 R117.00 R141.00 R189.00 Ramp R19.50 R36.00 R42.00 R54.00 SEBETIELA Ramp R19.50 R36.00 R45.00 R60.00 BAOBAB Mainline R48.50 R132.00 R181.00 R218.00 CAPRICORN Mainline R50.00 R137.00 R161.00 R201.00 R30 BRANDFORT Mainline R49.00 R98.00 R148.00 R208.00 N2 TSITSIKAMMA Mainline /Ramp R57.00 R144.00 R343.00 R486.00 IZOTSHA Ramp R10.00 R18.00 R24.00 R42.00 ORIBI Mainline R32.00 R57.00 R78.00 R127.00 Ramp (S) R14.50 R27.00 R36.00 R57.00 Ramp (N) -

[email protected]

17 November 2010 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION 100 F Street NE, Washington, D.C. 20549-0213. Via e-mail to: [email protected] Dear Sir / Madam SOUTH AFRICA VENTURE CAPITAL AND PRIVATE EQUITY ASSOCIATION (“SAVCA”) SUBMISSION TO THE SEC IN RESPECT OF REGISTRATION UNDER THE PRIVATE FUND INVESTMENT ADVISERS REGISTRATION ACT OF 2010. � Below is a submission to you from two of the largest independent private equity fund managers in South Africa, namely Ethos Private Equity Limited and Brait S.A. as members of SAVCA. In the event that you have any queries regarding the below submission or wish to interact with any of the role players you can make contact with the following people: Contact Designation e-mail address Telephone number J-P Fourie Executive Officer of SAVCA [email protected] +27 11 268 0041 Craig Dreyer CFO, Ethos Private Equity [email protected] +27 11 328 7424 Ltd Mark Parsons CFO, Private Equity Funds, [email protected] +27 11 507 1060 Brait S.A. We look forward to your feedback on our suggestions. Yours sincerely J-P Fourie Executive Officer PO Box 1140, Houghton, 2041, Suite N 204A, North Wing Office Block, Association incorporated in terms of Section 21, Reg. No. 2000/028170/08 204 Oxford Road, Thrupps Illovo Centre, Illovo, Johannesburg Directors: C Fernandez (Chairperson), C Dreyer, D Stadler, E du Toit, R Flett, Tel: +27 (0)11 268 0041 Fax: +27 (0)11 268 0527 F Gillion, P Helson, K Kunene, N Martin, N Mthembu, P Radebe, F Roji, [email protected] Executive Officer: J-P Fourie www.savca.co.za SUBMISSION TO THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION (SEC) IN RESPECT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR NON-RESIDENT INVESTMENT MANAGERS TO REGISTER UNDER THE PRIVATE FUND INVESTMENT ADVISERS REGISTRATION ACT OF 2010 The purpose of this paper is to provide you with background to the size of private equity commitments raised from US investors by non-resident private equity managers investing in South Africa, as well as regulations prevailing in South Africa. -

South Africa Country Operational Plan (COP)

FY 2015 South Africa Country Operational Plan (COP) The following elements included in this document, in addition to “Budget and Target Reports” posted separately on www.PEPFAR.gov, reflect the approved FY 2015 COP for South Africa. 1) FY 2015 COP Strategic Development Summary (SDS) narrative communicates the epidemiologic and country/regional context; methods used for programmatic design; findings of integrated data analysis; and strategic direction for the investments and programs. Note that PEPFAR summary targets discussed within the SDS were accurate as of COP approval and may have been adjusted as site- specific targets were finalized. See the “COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit” sheets that follow for final approved targets. 2) COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit includes approved COP 15 targets (targets to be achieved by September 30, 2016). As noted, these may differ from targets embedded within the SDS narrative document and reflect final approved targets. Approved FY 2015 COP budgets by mechanism and program area, and summary targets are posted as a separate document on www.PEPFAR.gov in the “FY 2015 Country Operational Plan Budget and Target Report.” Country Operational Plan (COP) 2015 Strategic Direction Summary September 30, 2015 Table of Contents Goal Statement 1.0 Epidemic Response and Program Context 1.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 1.2 Investment profile 1.3 Sustainability Profile 1.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 1.5 Stakeholder engagement 2.0 Core, Near-Core, -

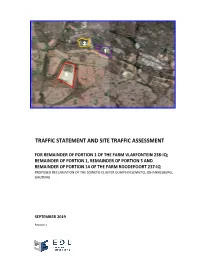

Traffic Statement and Site Traffic Assessment

TRAFFIC STATEMENT AND SITE TRAFFIC ASSESSMENT FOR REMAINDER OF PORTION 1 OF THE FARM VLAKFONTEIN 238‐IQ; REMAINDER OF PORTION 1, REMAINDER OF PORTION 5 AND REMAINDER OF PORTION 14 OF THE FARM ROODEPOORT 237‐IQ PROPOSED RECLAMATION OF THE SOWETO CLUSTER DUMPS IN SOWETO, JOHANNESBURG, GAUTENG SEPTEMBER 2019 Revision 1 TRAFFIC STATEMENT AND SITE TRAFFIC ASSESSMENT (REV 1) 19050 FOR REMAINDER OF PORTION 1 OF THE FARM VLAKFONTEIN 238‐IQ; REMAINDER OF PORTION 1, REMAINDER OF PORTION 5 AND REMAINDER OF PORTION 14 OF THE FARM ROODEPOORT 237‐IQ Issue/Revision Revision 1 Revision 2 Revision 3 Revision 4 Remarks For Information Date September 2019 Prepared by John v Rooyen Checked by Eben D. Kotze Pr Tech Eng Signature Project Number 19050 EDL Engineers (PTY) LTD t/a EDL Consulting Engineers 1 st Floor, Block D The Village Office Park C/o Glenwood Rd & Oberon Ave, Faerie Glen, 0043 Cell: +27 (0)83 564 1563 Tel: +27 (0)87 897 5074/5/6 Email: [email protected] www.EDLengineers.co.za EDL ENGINEERS (PTY) LTD 2 TRAFFIC STATEMENT AND SITE TRAFFIC ASSESSMENT (REV 1) 19050 FOR REMAINDER OF PORTION 1 OF THE FARM VLAKFONTEIN 238‐IQ; REMAINDER OF PORTION 1, REMAINDER OF PORTION 5 AND REMAINDER OF PORTION 14 OF THE FARM ROODEPOORT 237‐IQ Table of Contents Page No. 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................................