A Case Study of the Gauteng Freeway Improvement Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa: 1968

A survey of race relations in South Africa: 1968 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOO19690000.042.000 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org A survey of race relations in South Africa: 1968 Author/Creator Horrell, Muriel Publisher South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg Date 1969-01 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, Namibia Coverage (temporal) 1968 Source EG Malherbe Library Description A survey of race -

Happy Hunting Grounds for Ghost Stories

JOHAN DE SMIDT PHOTOGRAPHS Happy hunting grounds for ghost stories Once you’ve looked past the 1-Stops and the motels, the Great Karoo is more than a featureless highway between Joeys and Cape Town. Johan de Smidt found some great back roads and 4x4 tracks in the Nuweveld Mountains near Beaufort West. f you ask a Karoo sprawling sheep farms and beard Louis Alberts, over sheep farm 80 km west of farmer for a story, make the hunters have returned to nothing stronger than a cup Beaufort West. sure you don’t have far base camp, a ghost story is of coffee, mind you. We’re Flip has just unpacked to walk to your cottage probably what you’ll get. at Louis’ friends, Flip and his new jackal-foxing acqui- Iin the dark. Because once the Like the one we hear from Marge Vivier, on Rooiheuwel sition to show Louis. The winter sun has set over the the straight-shooting grey- Holiday Farm, a holiday and conflict between Karoo 28 DRIVE OUT NOVEMBER 2010 LONG WEEKEND GREAT KAROO The Karoo has mountains. A steep track at Badshoek leads to the base of Sneeukop, in the background. Afterwards, it’s straight down again. sheep farmer and jackal is “A group of hunters were previous Land Cruiser really An introduction at centuries old, with no end staying in the house some burnt out at the same house. Ko-Ka Tsara in sight. Out of the box time ago,” tells Louis. “One “It was about two or three Once you’ve realised how came a sound system featur- night, we were hunting on the in the morning; the same many diverse 4x4 trails and ing the latest in sound clips hills above the farm when we time a ghost would shake good gravel roads Beaufort to attract the sly sheep slay- saw the house burning. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

DISSERTATION O Attribution

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). The design of a vehicular traffic flow prediction model for Gauteng freeways using ensemble learning by TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA A dissertation submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Magister Commercii in Information Technology Management Faculty of Management UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Dr B.N Gatsheni 2016 DECLARATION I certify that the dissertation submitted by me for the degree Master’s of Commerce (Information Technology Management) at the University of Johannesburg is my independent work and has not been submitted by me for a degree at another university. TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I hereby wish to express my gratitude to the following individuals who enabled this document to be successfully and timeously completed: Firstly, GOD Supervisor, Dr BN Gatsheni Mikros Traffic Monitoring(Pty) Ltd (MTM) for providing me with the traffic flow data My family and friends Prof M Pillay and Ms N Eland Faculty of Management for funding me with the NRF Supervisor linked bursary ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to everyone who supported me during the project, from the start till the end. -

Everyone Loves E30s and This Triumvirate Must Rate As Three of The

040-048 BMWCAR 0314 07/02/2014 15:22 Page 40 Everyone loves E30s and this o finally the day has come where we can In the right corner the reigning world champion, measure up these legendary box-shaped the E30 M3, is painted in Lachs silver and weighs in triumvirate must rate as three beauties. This has to be one of the BMW (from new) at 1200kg and develops 200hp (140kW) showdowns of the century and who at 6750rpm and has a maximum torque of 177lb ft of the most desirable of the would have thought it would happen (238Nm) at 4750rpm. breed. The iconic M3 goes under African skies? Today is going to be a brawler; we are out in the In the left corner we have the two contenders, the west of the province of Gauteng approximately 40 head-to-head with the E30 333i and the E30 325iS Evolution. The 333i is kilometres outside of Johannesburg at the Delportan painted in Aero silver and weighs in at 1256kg. It Hill in Krugersdorp which has been a popular hillclimb South African-only 333i develops 197hp (145kW) at 5500rpm and has a venue since the ‘60s. We are in ‘Cradle’ country not and 325iS Evolution maximum torque of 210lb ft (285Nm) at 4300rpm. too far off from here are the Sterkfontein Caves – a The 325iS is painted in Ice white and weighs1147kg. World Heritage Site where ‘Mrs Ples’, a 2.1-million- Words: Johann Venter It develops 210hp (155kW) at 5920rpm, and has a year-old skull, and ‘Little Foot’, an almost complete Photography: Oliver Hirtenfelder maximum torque of 195lb ft (265Nm) at 4040rpm. -

Gauteng Gauteng

Gauteng Gauteng Thousands of visitors to South Africa make Gauteng their first stop, but most don’t stay long enough to appreciate all it has in store. They’re missing out. With two vibrant cities, Johannesburg and Tshwane (Pretoria), and a hinterland stuffed with cultural treasures, there’s a great deal more to this province than Jo’burg Striking gold International Airport, says John Malathronas. “The golf course was created in 1974,” said in Pimville, Soweto, and the fact that ‘anyone’ the manager. “Eighteen holes, par 72.” could become a member of the previously black- It was a Monday afternoon and the tees only Soweto Country Club, was spoken with due were relatively quiet: fewer than a dozen people satisfaction. I looked around. Some fairways were in the heart of were swinging their clubs among the greens. overgrown and others so dried up it was difficult to “We now have 190 full-time members,” my host tell the bunkers from the greens. Still, the advent went on. “It costs 350 rand per year to join for of a fully-functioning golf course, an oasis of the first year and 250 rand per year afterwards. tranquillity in the noisy, bustling township, was, But day membership costs 60 rand only. Of indeed, an achievement of which to be proud. course, now anyone can become a member.” Thirty years after the Soweto schoolboys South Africa This last sentence hit home. I was, after all, rebelled against the apartheid regime and carved ll 40 Travel Africa Travel Africa 41 ERIC NATHAN / ALAMY NATHAN ERIC Gauteng Gauteng LERATO MADUNA / REUTERS LERATO its name into the annals of modern history, the The seeping transformation township’s predicament can be summed up by Tswaing the word I kept hearing during my time there: of Jo’burg is taking visitors by R511 Crater ‘upgraded’. -

Hello Limpopo 2019 V7 Repro.Indd 1 2019/11/05 10:58 Driving the Growth of Limpopo

2019 LIMPOPOLIMPOPO Produced by SANRAL The province needs adequate national roads to grow the economy. As SANRAL, not only are we committed to our mandate to manage South Africa’s road infrastructure but we place particular focus on making sure that our roads are meticulously engineered for all road users. www.sanral.co.za @sanral_za @sanralza @sanral_za SANRAL SANRAL Corporate 5830 Hello Limpopo 2019 V7 Repro.indd 1 2019/11/05 10:58 Driving the growth of Limpopo DR MONNICA MOCHADI especially during high peak periods. We thus welcome the installation of cutting-edge technology near the he Limpopo provincial government is committed Kranskop Toll Plaza in Modimolle which have already to the expansion and improvement of our primary contributed to a reduction in fatalities on one of the Troad network. busiest stretches of roads. Roads play a critical role in all of the priority SANRAL’s contribution to the transformation of the economic sectors identified in the Provincial Growth construction sector must be applauded. An increasing and Development Strategy, most notably tourism, number of black-owned companies and enterprises agriculture, mining and commerce. The bulk of our owned by women are now participating in construction products and services are carried on the primary road and road maintenance projects and acquiring skills that network and none of our world-class heritage and will enable them to grow and create more jobs. tourism sites would be accessible without the existence This publication, Hello Limpopo, celebrates the of well-designed and well-maintained roads. productive relationship that exists between the South It is encouraging to note that some of the critical African National Roads Agency and the province of construction projects that were placed on hold have Limpopo. -

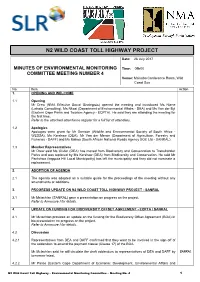

N2 Wild Coast Toll Highway Project

N2 WILD COAST TOLL HIGHWAY PROJECT Date: 26 July 2017 MINUTES OF ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING Time: 09h00 COMMITTEE MEETING NUMBER 4 Venue: Msikaba Conference Room, Wild Coast Sun No. Item Action 1. OPENING AND WELCOME 1.1 Opening Mr Drew (NMA Effective Social Strategists) opened the meeting and introduced Ms Ntene (Letsolo Consulting), Ms Nkosi (Department of Environmental Affairs - DEA) and Ms Van der Byl (Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism Agency - ECPTA). He said they are attending the meeting for the first time. Refer to the attached attendance register for a full list of attendees. 1.2 Apologies Apologies were given for Mr Denison (Wildlife and Environmental Society of South Africa - WESSA), Ms Kershaw (DEA), Mr Van der Merwe (Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries - DAFF) and Ms Makoa (South African National Roads Agency SOC Ltd - SANRAL). 1.3 Member Representatives Mr Drew said Ms Olivier (DEA) has moved from Biodiversity and Conservation to Transfrontier Parks and was replaced by Ms Kershaw (DEA) from Biodiversity and Conservation. He said Mr Pantshwa (Ingquza Hill Local Municipality) has left the municipality and they did not nominate a replacement. 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA 2.1 The agenda was adopted as a suitable guide for the proceedings of the meeting without any amendments or additions. 3. PROGRESS UPDATE ON N2 WILD COAST TOLL HIGHWAY PROJECT - SANRAL 3.1 Mr Mclachlan (SANRAL) gave a presentation on progress on the project. Refer to Annexure I for details. 4. UPDATE ON FUNDING FOR BIODIVERSITY OFFSET AGREEMENT - ECPTA / SANRAL 4.1 Mr Mclachlan provided an update on the funding for the Biodiversity Offset Agreement (BOA) in his presentation on progress on the project. -

Albert Luthuli Local Municipality 2013/14

IDP REVIEW 2013/14 IIntegrated DDevelopment PPlan REVIEW - 2013/14 “The transparent, innovative and developmental local municipality that improves the quality of life of its people” Published by Chief Albert Luthuli Local Municipality Email: [email protected] Phone: (017) 843 4000 Website: www.albertluthuli.gov.za IDP REVIEW 2013/14 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms 6 A From the desk of the Executive Mayor 7 B From the desk of the Municipal Manager 9 PART 1- INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1 INTRODUCTION 11 1.2 STATUS OF THE IDP 11 1.2.1 IDP Process 1.2.1.1 IDP Process Plan 1.2.1.2 Strategic Planning Session 1.3 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 12 1.4 INTER GOVERNMENTAL PLANNING 13 1.4.1 List of Policies 14 1.4.2 Mechanisms for National planning cycle 15 1.4.3 Outcomes Based Approach to Delivery 16 1.4.4 Sectoral Strategic Direction 16 1.4.4.1 Policies and legislation relevant to CALM 17 1.4.5 Provincial Growth and Development Strategy 19 1.4.6 Municipal Development Programme 19 1.5 CONCLUSION 19 PART 2- SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 2.1 BASIC STATISTICS AND SERVICE BACKLOGS 21 2.2 REGIONAL CONTEXT 22 2.3 LOCALITY 22 2.3.1 List of wards within municipality with area names and coordinates 23 2.4 POPULATION TRENDS AND DISTRIBUTION 25 2.5 SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT 29 2.5.1 Land Use 29 2.5.2 Spatial Development Framework and Land Use Management System 29 Map: 4E: Settlement Distribution 31 Map 8: Spatial Development 32 2.5.3 Housing 33 2.5.3.1 Household Statistics 33 2.5.4 Type of dwelling per ward 34 2.5.5 Demographic Profile 34 2.6 EMPLOYMENT TRENDS 39 2.7 INSTITUTIONAL -

Rooftop Solar PV Potential Assessment in the City of Johannesburg

Rooftop Solar PV Potential Assessment in the City of Johannesburg by Moroasereme Ntsoane Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sustainable Development in the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Alan Brent March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i | Page Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Cities are the modern era’s undisputed drivers for economic growth and development. But cities are also highly energy and resource intensive. Therefore, it is predictable that cities would be active participants in the global effort to creatively strike a balance between resources consumption and economic growth for a sustainable future. Part of this is exploiting the often neglected, but vital, solar photovoltaic (PV) resource and rooftop real estate within cities. At face value, a city with the real estate infrastructural sophistication of the City of Johannesburg (CoJ), presents an attractive opportunity for generating renewable energy from its building rooftops. However, the magnitude of this potential is yet to be fully characterised. Assessments of the rooftop solar PV potential of buildings in inner city locale are made complex by the variety of building typologies and rooftop accessibility. -

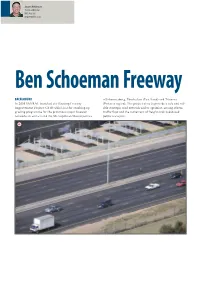

Ben Schoeman Freeway

Jurgens Weidemann Technical Director BKS (Pty) Ltd [email protected] Ben Schoeman Freeway BACKGROUND of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni (East Rand) and Tshwane In 2008 SANRAL launched the Gauteng Freeway (Pretoria region). The project aims to provide a safe and reli- Improvement Project (GFIP) which is a far-reaching up- able strategic road network and to optimise, among others, grading programme for the province’s major freeway traffic flow and the movement of freight and road-based networks in and around the Metropolitan Municipalities public transport. 1 The GFIP is being implemented in phases. The first phase 1 Widened to five lanes per carriageway comprises the improvement of approximately 180 km of 2 Bridge widening at the Jukskei River existing freeways and includes 16 contractual packages. The 3 Placing beams at Le Roux overpass network improvement comprises the adding of lanes and up- 4 Brakfontein interchange – adding a third lane grading of interchanges. Th e upgrading of the Ben Schoeman Freeway (Work Package 2 C of the GFIP) is described in this article. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES Th e upgraded and expanded freeways will signifi cantly re- duce traffi c congestion and unblock access to economic op- portunities and social development projects. Th e GFIP will provide an interconnected freeway system between the City of Johannesburg and the City of Tshwane, this system currently being one of the main arteries within the north-south corridor. One of the most significant aims of this investment for ordinary citizens is the reduction of travel times since many productive hours are wasted as a result of long travel times. -

Final E-Toll and GFIP Report+V20

The socio-economic impact of the Gauteng Freeway Improvement Project and E-tolls Report Report of the Advisory Panel appointed by Gauteng Premier, Mr David Makhura 30 November 2014 GAUTENG PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Socio-economic Impact Gauteng Freeway Improvement Project and E-tolls Table of contents Part One: Preamble, Preface and Executive Summary Preamble ...................................................................................................................................................... i Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... vi Members of the Advisory Panel ................................................................................................................ vii Executive summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background to the recommendations of the Panel ...................................................................... 3 3. Recommendations ........................................................................................................................