YU Students' Engagement with the Crises of Their Times: Benjamin Koslowe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968

THE POLITICS OF SPACE: STUDENT COMMUNES, POLITICAL COUNTERCULTURE, AND THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PROTEST OF 1968 Blake Slonecker A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Peter Filene Reader: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Reader: Jerma Jackson © 2006 Blake Slonecker ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT BLAKE SLONECKER: The Politics of Space: Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968 (Under the direction of Peter Filene) This thesis examines the Columbia University protest of April 1968 through the lens of space. It concludes that the student communes established in occupied campus buildings were free spaces that facilitated the protestors’ reconciliation of political and social difference, and introduced Columbia students to the practical possibilities of democratic participation and student autonomy. This thesis begins by analyzing the roots of the disparate organizations and issues involved in the protest, including SDS, SAS, and the Columbia School of Architecture. Next it argues that the practice of participatory democracy and maintenance of student autonomy within the political counterculture of the communes awakened new political sensibilities among Columbia students. Finally, this thesis illustrates the simultaneous growth and factionalization of the protest community following the police raid on the communes and argues that these developments support the overall claim that the free space of the communes was of fundamental importance to the protest. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Peter Filene planted the seed of an idea that eventually turned into this thesis during the sort of meeting that has come to define his role as my advisor—I came to him with vast and vague ideas that he helped sharpen into a manageable project. -

MS and Grad Certificate in Human Rights

NEW ACADEMIC PROGRAM – IMPLEMENTATION REQUEST I. PROGRAM NAME, DESCRIPTION AND CIP CODE A. PROPOSED PROGRAM NAME AND DEGREE(S) TO BE OFFERED – for PhD programs indicate whether a terminal Master’s degree will also be offered. MA in Human Rights Practice (Online only) B. CIP CODE – go to the National Statistics for Education web site (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/browse.aspx?y=55) to select an appropriate CIP Code or contact Pam Coonan (621-0950) [email protected] for assistance. 30.9999 Multi-/Interdisciplinary Studies, Other. C. DEPARTMENT/UNIT AND COLLEGE – indicate the managing dept/unit and college for multi- interdisciplinary programs with multiple participating units/colleges. College of Social & Behavioral Sciences D. Campus and Location Offering – indicate on which campus(es) and at which location(s) this program will be offered (check all that apply). Degree is wholly online II. PURPOSE AND NATURE OF PROGRAM–Please describe the purpose and nature of your program and explain the ways in which it is similar to and different from similar programs at two public peer institutions. Please use the attached comparison chart to assist you. The MA in Human Rights Practice provides online graduate-level education for human rights workers, government personnel, and professionals from around the globe seeking to further their education in the area of human rights. It will also appeal to recent undergraduate students from the US and abroad with strong interests in studying social justice and human rights. The hallmarks of the proposed -

Academic Catalog 2015-‐‑2016

1 ACADEMIC CATALOG 2015-2016 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS • OFFICERS & TRUSTEES ................................................................................................. 4 • ACADEMIC CALENDAR ............................................................................................... 8 • ADMISSIONS ................................................................................................................ 14 • FINANCIAL AID ........................................................................................................... 21 • HOUSING AT TEACHERS COLLEGE ............................................................................. 22 • ACADEMIC RESOURCES AND SERVICES ..................................................................... 28 • STUDENT LIFE AND STUDENT SERVICES ..................................................................... 56 • REGISTRATION ............................................................................................................ 64 • GENERAL REQUIREMENTS .......................................................................................... 69 • POLICIES & PROCEDURES ............................................................................................ 75 • ACCESS TO SERVICES • ACCREDITATION • ATTENDANCE • CREDIT AND NONCREDIT COURSES • DEFINITION OF POINT CREDIT • FERPA • GRADES • GRADUATE CREDIT IN ADVANCED COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES • HEGIS CODES • INTER-UNIVERSITY DOCTORAL CONSORTIUM • NON-DISCRIMINATION POLICY • OFFICIAL COLLEGE -

Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: a Retrospective View

Copyrighted material. Do not duplicate. Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: A Retrospective View IRVING (YITZ) GREENBERG he Oxford conference of 2014 set off a wave of self-reflection, with particu- Tlar reference to my relationship to and role in Modern Orthodoxy. While the text below includes much of my presentation then, it covers a broader set of issues and offers my analyses of the different roads that the leadership of the community and I took—and why.1 The essential insight of the conference was that since the 1960s, Modern Orthodoxy has not taken the road that I advocated. However, neither did it con- tinue on the road it was on. I was the product of an earlier iteration of Modern Orthodoxy, and the policies I advocated in the 1960s could have been projected as the next natural steps for the movement. In the course of taking a different 1 In 2014, I expressed appreciation for the conference’s engagement with my think- ing, noting that there had been little thoughtful critique of my work over the previous four decades. This was to my detriment, because all thinkers need intelligent criticism to correct errors or check excesses. In the absence of such criticism, one does not learn an essential element of all good thinking (i.e., knowledge of the limits of these views). A notable example of a rare but very helpful critique was Steven Katz’s essay “Vol- untary Covenant: Irving Greenberg on Faith after the Holocaust,” inHistoricism, the Holocaust, and Zionism: Critical Studies in Modern Jewish Thought and History, ed. -

The Piaseczner Rebbe Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira and the Philosopher

“Mending the World” in Approaches of Hassidism and Reform Judaism: The Piaseczner Rebbe Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira and the philosopher Emil L. Fackenheim on the Holocaust By Anna Kupinska Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Carsten Wilke Second Reader: Professor Michael Laurence Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection Abstract Holocaust raised many theological and philosophical problems that questioned and doubted all previous human experience. Many believers asked is it possible to keep faith in God after mass exterminations, many thinkers were concerned with a future of philosophy that seemed to lose its value, facing unspeakable and unthinkable. There was another ontological question – how to fix all the damage, caused by Holocaust (if it is possible at all), how to prevent new catastrophes and to make the world a better place to live. On a junction of these problems two great works appeared – Esh Kodesh (The Holy Fire) by Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira and To Mend the World by Emil Fackenheim. The first was a Hassidic leader, the Rabbi of the Polish town Piaseczno and also the Rabbi in the Warsaw ghetto, who didn’t survive Holocaust but spent rest of his days, helping and comforting his Hasidim likewise other fellow Jews. -

From Philantrophy and Household Arts to the Scholarly Education of Psychologists and Educators: a Brief History of the University of Columbia's Teachers College (1881-1930)

Revista de Historia de la Psicología, 2019, Vol. 40(4), 11–23 Revista de Historia de la Psicología www.revistahistoriapsicologia.es From Philantrophy and Household Arts to the Scholarly Education of Psychologists and Educators: A Brief History of the University of Columbia’s Teachers College (1881-1930) Catriel Fierro Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata. Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Argentina INFORMACIÓN ART. ABSTRACT Recibido: 13 octubre 2019 During the professionalization of American psychology towards the end of the 19th century, the Aceptado: 18 noviembre 2019 pedagogical field, with its institutions, educational departments and teacher’s schools, represented one of the main ‘niches’ or focal points of study and disciplinary application for emerging graduates Key words in the new science. The present study constitutes a historical analysis of Teachers College, an academic professionalization of Psychology, Teachers College, and professional institution linked to Columbia University, a pioneer in the education and training of University of Columbia, American educators with international projections, between 1881 and 1930. Based on the use of various social history, primary sources and archival documents not analyzed in previous works, a critical contextualization of educational psychology the emergence of the College, and a narrative of its institutional, scientific and curricular development of the institution are offered. It shows the transit of Teachers College from a nonprofit -

Finding Aid Aggregation at a Crossroads

Finding Aid Aggregation at a Crossroads Prepared by Jodi Allison-Bunnell, AB Consulting Edited by Adrian Turner, California Digital Library 2019 May 20 ! This report was prepared for "Toward a National Finding Aid Network," a one-year planning initiative supported by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA), administered in California by the State Librarian Table of Contents Executive Summary 2 Foundational Assumptions 3 Key Findings 3 Introduction 5 Methodology 5 Findings 6 Purpose and Value 6 Coverage and Scope 6 Resources 7 Infrastructure 7 End Users 8 Data Structure and Content 8 Organizational Considerations 9 A Composite Profile of Aggregators and Meta-Aggregators 9 Statewide and Regional Coverage of Aggregators 10 Extent of Institutions Contributing to Aggregators 11 Extent of Finding Aids Hosted by Aggregators 11 Growth Rate of Aggregators 12 Finding Aid Formats Hosted by Aggregators and Meta-Aggregators 13 Organizational Histories of Aggregators and Meta-Aggregators 14 User Audiences Served by Aggregations and Meta-Aggregators 16 Value Proposition: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Aspirations of Aggregators and Meta- Aggregators 16 Organizational Lifecycle Stages and Vitality of Aggregators and Meta-Aggregators 18 Infrastructure Used by Aggregators and Meta-Aggregators 20 Governance of Aggregations and Meta-Aggregations 23 Resources to Support Aggregations and Meta-Aggregations 23 Defunct Aggregations 28 Individual Archival Repositories and Relationships -

Download This Issue As A

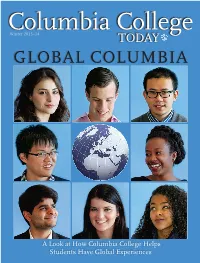

Columbia College Winter 2013–14 TODAY GLOBAL COLUMBIA A Look at How Columbia College Helps Students Have Global Experiences Contents GLOBAL COLUMBIA give A SPECIAL SECTION yourself a gift 20 How the College Helps Students Have Global Experiences Now more than ever, the College is taking steps to ensure that its students are THIS HOLIDAY SEASON, thinking globally, opening their minds to and setting their sights on the world TREAT YOURSELF TO THE beyond Morningside Heights. BY SHIRA BOss ’93, ’97J, ’98 SIPA BENEFITS AND PRIVILEGES OF 28 A Conversation with President Lee C. Bollinger THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CLUB Bollinger talks about the philosophy behind the Columbia Global Centers, their impact OF NEW YORK now and in the future, and what it means to be a global citizen in the 21st century. AQ &A WITH CCT EDITOR ALEX SACHARE ’71 32 Global Students Find a Home at Columbia International students reflect on their reasons for choosing the College and their experiences in making the cultural and academic transition. BY NATHALIE ALOnsO ’08 36 Study Abroad Grows in Popularity, Programs and Places New programs and destinations give students myriad ways to enhance their College education with an international experience. Plus: Excerpts from a blog kept by Melissa Chiang ’14 last summer in Shanghai. BY TED RABINOWITZ ’87 BECOME A MEMBER! 40 For Global Alumni, Columbia Made a World of Difference JOIN TODAY! College alumni often trace their success living and working internationally to their liberal arts education, the diverse Columbia student body and the unique nature of New York City. 15 WEST 43 STREET NEW YORK, NY 10036 BY TED RABINOWITZ ’87 TEL: 212.719.0380 www.columbiaclub.org YOUR COLUMBIA CONNECTION COVER PHOTOS: CHAR SMULLYAN; GLOBE ICON: ILLUSTRATION BY R.J. -

Peter F. Andrews Sportswriting and Broadcasting Resume [email protected] | Twitter: @Pfandrews | Pfandrews.Wordpress.Com

Peter F. Andrews Sportswriting and Broadcasting Resume [email protected] | Twitter: @pfandrews | pfandrews.wordpress.com RELEVANT EXPERIENCE Philly Soccer Page Staff Writer & Columnist, 2014-present: Published over 100 posts, including match reports, game analysis, commentary, and news recaps, about the Philadelphia Union and U.S. National Teams. Covered MLS matches, World Cup qualifiers, Copa America Centenario matches, and an MLS All-Star Game at eight different venues across the United States and Canada. Coordinated the launch of PSP’s Patreon campaign, which helps finance the site. Appeared as a guest on one episode of KYW Radio’s “The Philly Soccer Show.” Basketball Court Podcast Host & Producer, 2016-present: Produced a semi-regular podcast exploring the “what-ifs” in the history of the National Basketball Association, presented in a humorous faux-courtroom style. Hosted alongside Sam Tydings and Miles Johnson. Guests on the podcast include writers for SBNation and SLAM Magazine. On The Vine Podcast Host & Producer, 2014-present: Produced a weekly live podcast on Mixlr during the Ivy League basketball season with writers from Ivy Hoops Online and other sites covering the league. Co-hosted with IHO editor-in- chief Michael Tony. Featured over 30 guests in three seasons. Columbia Daily Spectator Sports Columnist, Fall 2012-Spring 2014: Wrote a bi-weekly column for Columbia’s student newspaper analyzing and providing personal reflections on Columbia’s athletic teams and what it means to be a sports fan. Spectrum Blogger, Fall 2013: Wrote a series of blog posts (“All-22”) which analyzed specific plays from Columbia football games to help the average Columbia student better understand football. -

Physical Education and Athletics at Horace Mann, Where the Life of the Mind Is Strengthened by the Significance of Sports

magazine Athletics AT HORACE MANN SCHOOL Where the Life of the Mind is strengthened by the significance of sports Volume 4 Number 2 FALL 2008 HORACE MANN HORACE Horace Mann alumni have opportunities to become active with their School and its students in many ways. Last year alumni took part in life on campus as speakers and participants in such dynamic programs as HM’s annual Book Day and Women’s Issues Dinner, as volunteers at the School’s Service Learning Day, as exhibitors in an alumni photography show, and in alumni athletic events and Theater For information about these and other events Department productions. at Horace Mann, or about how to assist and support your School, and participate in Alumni also support Horace Mann as participants in HM’s Annual Fund planning events, please contact: campaign, and through the Alumni Council Annual Spring Benefit. This year alumni are invited to participate in the Women’s Issues Dinner Kristen Worrell, on April 1, 2009 and Book Day, on April 2, 2009. Book Day is a day that Assistant Director of Development, engages the entire Upper Division in reading and discussing one literary Alumni Relations and Special Events work. This year’s selection is Ragtime. The author, E.L. Doctorow, will be the (718) 432-4106 or keynote speaker. [email protected] Upcoming Events November December January February March April May June 5 1 3 Upper Division Women’s HM Alumni Band Concert Issues Dinner Council Annual Spring Benefit 6-7 10 6 2 6 5-7 Middle Robert Buzzell Upper Division Book Day, Bellet HM Theater Division Memorial Orchestra featuring Teaching Alumni Theater Games Concert E.L. -

ANTHONY COCCIOLO [email protected]

144 W. 14th St., 6th Floor New York, NY 10011 +1 212-647-7702 ANTHONY COCCIOLO [email protected] www.thinkingprojects.org EDUCATION • Teachers College, Columbia University Ed.D., Communication, Media and Learning Technologies Design (2005-2009) Dissertation Title: Using Information and Communications Technologies to Advance a Participatory Culture: A Study from a Higher Education Context [PDF] Dissertation Committee: Charles Kinzer, Gary Natriello, Lalitha Vasudevan and Jeanne Bitterman Ed.M., Communication, Media and Learning Technologies Design (2005-2008) M.A., Communication, Media and Learning Technologies Design (2003-2005) • University of California, Riverside (9/1998 to 3/2002) B.S., Computer Science (with honors) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE • Pratt Institute, School of Information, New York, NY (8/2009 to current) Interim Dean (7/2017 to current) Associate Professor (9/2014 to current, tenure granted in 2016) Coordinator of Advanced Certificate in Archives (8/2009 to current) MSLIS Program Coordinator (3/2016 to 6/2017) Assistant Professor (8/2009 to 8/2014) Oversee all School of Information academic and administrative operations. As professor, perform research and teaching in area of archives and digital preservation. • Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY (5/2002 to 8/2009) Head of Technology, EdLab and The Gottesman Libraries New York, NY (5/2002 to 8/2009) Lead, develop and manage a variety of digital initiatives and services. • Datagenix, LLC, Riverside, CA (10/2000 to 4/2002) Applications Developer Develop software products and applications for clients. • University of California, Riverside (12/1998 to 3/2002) Student Research Assistant, Department of Earth Science Develop interactive project website. PUBLICATIONS & PRESENTATIONS Monographs 2 • Cocciolo, A. -

June 2011 Jewish News

Shabbat & Holiday Candle Lighting Times Allocations Decisions Diffi cult, Friday, June 3 8:08pm Overseas Percentage Increased Tuesday, June 7 8:10pm The Savannah Jewish Federation’s song kept playing through my mind. Wednesday, June 8 8:11pm Allocation Committee is a committee “In this world of ordinary people, Friday, June 10 8:12pm of about 20 individuals, balanced from extraordinary people, I’m glad there across synagogues and organizations is you.” Finding songs to fi t events is “The Allocations committee Friday, June 17 8:14pm and represents various interests and not unusual for me, but these words did a fabulous job making the Friday, June 24 8:16pm perspectives of the community. Dur- seemed to be set on replay, just like ing these still challenging economic Johnny Mathis was at my house when hard decisions. I applaud them” Friday, July 1 8:17pm times and a period of changes in our I was a teenager. Friday, July 8 8:16pm Jewish community, raising the dollars Each person at the meeting was, ination? Yes! Friday, July 15 8:14pm and deciding how to allocate them was to me, extraordinary. No one missed Instead, I believe that we all diffi cult. one of the three meetings. No one left were searching for ways to make next Sitting on the Allocations Commit- early. As a teacher, used to looking at year’s campaign more successful. Nat- In This Issue tee for many meant having to put per- a group and seeing who is and who is urally, all of us hope that the general Shaliach’s message, p2 sonal loyalties to the side and focus on not engaged in the discussion, I knew economy improves for more reasons Letter to the Editor, p2 what is best for our Savannah Jewish that every single person was paying than the Federation campaign.