Saudi Arabia's Creative Change of (He)Art?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country City Sitename Street Name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St

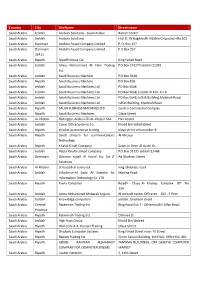

Country City SiteName Street name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St. W.Bogddadih AlZabin Cmpound villa 102 Saudi Arabia Damman Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P. O. Box 257 Saudi Arabia Dammam Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P O Box 257 31411 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Riyadh House Est. King Fahad Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Idress Mohammed Ali Fatni Trading P.O.Box 132270 Jeddah 21382 Est. Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machine P.O.Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machine P.O Box 818 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd PO Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Jeddah 21432, K S A Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Juffali Building,Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. Juffali Building, Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Riyadh SAUDI BUSINESS MACHINES LTD. Centria Commercial Complex Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machines Olaya Street Saudi Arabia Al-Khobar Redington Arabia LTD AL-Khobar KSA Hail Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Canar Office Systems Co Khalid Bin Walid Street Saudi Arabia Riyadh shrakat partnerships trading olaya street villa number 8 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Unicom for communications Al-Mrouje technology Saudi Arabia Riyadh Khalid Al Safi Company Salah Al-Deen Al-Ayubi St., Saudi Arabia Jeddah Azizia Panda United Company P.O.Box 33333 Jeddah 21448 Saudi Arabia Dammam Othman Yousif Al Yousif Est. for IT Ad Dhahran Street Solutions Saudi Arabia Al Khober al hasoob al asiavy est. king abdulaziz road Saudi Arabia Jeddah EchoServe-Al Sada Al Shamila for Madina Road Information Technology Co. -

(Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with the Description of Two New Species

European Journal of Taxonomy 246: 1–36 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2016.246 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2016 · Sharaf M.R. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:966C5DFD-72A9-4567-9DB7-E4C56974DDFA Taxonomy and distribution of the genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with the description of two new species Mostafa R. SHARAF 1,*, Shehzad SALMAN 2, Hathal M. AL DHAFER 3, Shahid A. AKBAR 4, Mahmoud S. ABDEL-DAYEM 5 & Abdulrahman S. ALDAWOOD 6 1,2,3,5,6 Plant Protection Department, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, P. O. Box 2460, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 4 Central Institute of Temperate Horticulture, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 E-mail: [email protected] 3 E-mail: [email protected] 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 E-mail: [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:E2A42091-0680-4A5F-A28A-2AA4D2111BF3 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:394BE767-8957-4B61-B79F-0A2F54DF608B 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6117A7D3-26AF-478F-BFE7-1C4E1D3F3C68 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5A0AC4C2-B427-43AD-840E-7BB4F2565A8B 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:AAAD30C4-3F8F-4257-80A3-95F78ED5FE4D 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:477070A0-365F-4374-A48D-1C62F6BC15D1 Abstract. The ant genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865 is revised for the Arabian Peninsula based on the worker caste. Nine species are recognized and descriptions of two new species, T. -

Rising Tourism in Saudi Arabia: Implications for Real Estate Investment

Rising Tourism in Saudi Arabia: Implications For Real Estate Investment Author: Ali S Daye Ali Daye will graduate from the Baker Program in Real Estate in 2019 with a concentration in development and sustainability. Prior to Cornell, Ali received a Master’s of Construction Management from NC A&T State University. During his 10-year career in the construction industry, he was involved in the buildouts of many large-scale projects while working for major construction management firms. Upon completion of the Baker Program, Ali intends to pursue a career in international real estate and development, with a focus on sustainability, concentrating in the markets of the Gulf Cooperation Council. 98 INTRODUCTION Over the last few years, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has pursued a more aggressive approach towards economic diversification in order to plan for the future of its youth as nearly 60 percent of the country’s 3 million citizens are under the age of 30 (KSA-General Authority for Statics, 2017). Saudi Arabia traditionally has relied heavily on the public sector to absorb many of the educated Saudi nationals. However, the country is now looking to the private sector to create more jobs for its burgeoning population and has enacted policies that ease doing business in the country and make it more accessible to the outside world. Considered one of the world’s most insular nations, Saudi restructuring, focusing on projects that support the country’s Arabia is now investing billions of dollars to become more Vision 2030 plans as well as making major investments open under its Vision 2030 reform program. -

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

White Paper Makkah | Retail 2018 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Evolving Dynamics Makkah Retail Overview Summary The holy city of Makkah is currently going through a major strategic development phase to improve connectivity, Ian Albert increase capacity, and enhance the experience of Umrah Regional Director and Hajj pilgrims throughout their stay. Middle East & North Africa This is reflected in the execution of several strategic infrastructure and transportation projects, which have a clear focus on increasing pilgrim capacity and improving connectivity with key projects, including the Holy Haram Expansion, Haramain High- Speed Railway, and King Abdulaziz International Airport. These projects, alongside Vision 2030, are shaping the city’s real estate landscape and stimulating the development of several large real estate projects in their surrounding areas, including King Abdulaziz Road (KAAR), Jabal Omar, Thakher City and Ru’a Al Haram. These projects are creating opportunities for the development of various retail Imad Damrah formats that target pilgrims. Managing Director | Saudi Arabia Makkah has the lowest retail density relative to other primary cities; Riyadh, Jeddah, Dammam Al Khobar and Madinah. With a retail density of c.140 sqm / 1,000 population this is 32% below Madinah which shares the same demographics profile. Upon completion of major transport infrastructure and real estate projects the number of pilgrims is projected to grow by almost 223% from 12.1 million in 2017 up to 39.1 million in 2030 in line with Vision 2030 targets. Importantly the majority of international Pilgrims originate from countries with low purchasing power. Approximately 59% of Hajj and Umrah pilgrims come from countries with GDP/capita below USD 5,000 (equivalent to SAR 18,750). -

DNA Barcoding of the Fire Ant Genus Solenopsis Westwood

Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 27 (2020) 184–188 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com Original article DNA barcoding of the fire ant genus Solenopsis Westwood (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Riyadh region, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia ⇑ Khawaja Ghulam Rasool a, , Mureed Husain a, Shehzad Salman a, Muhammad Tufail a,b, Sukirno Sukirno c, Abdulrahman S. Aldawood a a Department of Plant Protection, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia b Ghazi University, Dera Ghazi Khan, Punjab, Pakistan c Entomology Laboratory, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia article info abstract Article history: The ant genus Solenopsis Westwood, 1840 is the largest in Myrmicinae subfamily having almost 200 Received 29 April 2019 described species worldwide. They are commonly distributed in the tropics and temperate areas of the Revised 18 June 2019 world. Some invasive Solenopsis species are very dreadful. We have already reported a fire ant species, Accepted 30 June 2019 Solenopsis saudiensis Sharaf & Aldawood, 2011, identified using traditional morphometric approaches of Available online 2 July 2019 species identification. Present study was carried out to develop DNA Barcoding to identify Solenopsis sau- diensis and to elucidate genetic structure of the various S. saudiensis populations across their distribution Keywords: range in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The comparison of DNA barcodes showed no genetic diversity among six Fire ant populations and a queen from S. saudiensis analyzed from the Riyadh region. This genetic resemblance DNA barcoding Cytochrome C oxidase I probably reflects their adaptation toward a specific habitat, thus constituting a single and strong gene Biodiversity pool. -

The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 7: The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The Ministry for Islamic Affairs, Endowments, Da’wah, and Guidance, commonly abbreviated to the Ministry of Islamic Affairs (MOIA), supervises and regulates religious activity in Saudi Arabia. Whereas the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) directly enforces religious law, as seen in Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 1,1 the MOIA is responsible for the administration of broader religious services. According to the MOIA, its primary duties include overseeing the coordination of Islamic societies and organizations, the appointment of clergy, and the maintenance and construction of mosques.2 Yet, despite its official mission to “preserve Islamic values” and protect mosques “in a manner that fits their sacred status,”3 the MOIA is complicit in a longstanding government campaign against the peninsula’s traditional heritage – Islamic or otherwise. Since 1925, the Al Saud family has overseen the destruction of tombs, mosques, and historical artifacts in Jeddah, Medina, Mecca, al-Khobar, Awamiyah, and Jabal al-Uhud. According to the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, between just 1985 and 2014 – through the MOIA’s founding in 1993 –the government demolished 98% of the religious and historical sites located in Saudi Arabia.4 The MOIA’s seemingly contradictory role in the destruction of Islamic holy places, commentators suggest, is actually the byproduct of an equally incongruous alliance between the forces of Wahhabism and commercialism.5 Compelled to acknowledge larger demographic and economic trends in Saudi Arabia – rapid population growth, increased urbanization, and declining oil revenues chief among them6 – the government has increasingly worked to satisfy both the Wahhabi religious establishment and the kingdom’s financial elite. -

Solar and Shading Potential of Different Configurations of Building

sustainability Article Solar and Shading Potential of Different Configurations of Building Integrated Photovoltaics Used as Shading Devices Considering Hot Climatic Conditions Omar S. Asfour Department of Architecture, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, P.O. Box 2483, Dhahran 31261, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +966-13-860-3594; Fax: +966-13-860-3210 Received: 23 October 2018; Accepted: 21 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: This study investigates the use of building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs) as shading devices in hot climates, with reference to the conditions of Saudi Arabia. It used parametric numerical modelling to critically appraise the potential of eight design configurations in this regard, including vertical and horizontal shading devices with different inclination angles. The study assumed that the examined shading devices could be entirely horizontal or vertical on the three exposed facades, which is common practice in architecture. The study found that the examined configurations offered different solar and shading potentials. However, the case of horizontal BIPV shading devices with a 45◦ tilt angle received the highest amount of annual total insolation (104 kWh/m2) and offered effective window shading of 96% of the total window area on average in summer. The study concluded that, unlike the common recommendation of avoiding horizontal shading devices on eastern and western facades, it is possible in countries characterised with high solar altitudes such as Saudi Arabia to use them effectively to generate electricity and provide the required window shading. Keywords: building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs); solar energy; shading devices; architecture; Saudi Arabia 1. -

Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS THE HIGH COST OF CHANGE Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms WATCH The High Cost of Change Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37793 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37793 The High Cost of Change Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ................................................................................................................7 To the Government of Saudi Arabia ........................................................................................ -

ECFG-Saudi-Arabia-2020.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The ECFG fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Saudi soldiers perform a traditional dance). Kingdomof Saudi Arabia The guide consists of two parts: Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on the Arab Gulf States. NOTE: While the term Persian Gulf is common in the US, this guide uses the name preferred in the region, the Arabian Gulf. Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Saudi society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: US soldiers dine on a traditional Saudi meal of lamb and rice). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at http://culture.af.mil/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Saudi Arabia HVAC-R Market Outlook, 2021

Saudi Arabia HVAC-R Market Outlook, 2021 Market Intelligence . Consulting Table of Contents S. No. Contents Page No. 1. Saudi Arabia HVAC-R: Key Projects 5 2. Saudi Arabia Thermal Insulation Market Outlook 12 2.1. Market Size & Forecast 2.1.1. By Value 13 2.2. Market Share & Forecast 2.2.1. By Type 14 2.2.2 By Application 15 3. Saudi Arabia District Cooling Market Outlook 16 3.1. Market Size & Forecast 3.1.1. By Value & Volume 17 4. Saudi Arabia Refrigeration Market Outlook 19 4.1. Market Size & Forecast 4.1.1. By Value 20 5. Saudi Arabia HVAC-R Market Outlook 21 5.1. Market Size & Forecast 5.1.1. By Value 23 5.2. Market Share & Forecast 5.2.1. By Region 25 6. Sustainability and Energy Saving in HVAC-R Saudi Arabia Market 30 7. About Us & Disclaimer 37 2 8. About HVACR Expo Saudi 38 © TechSci Research List of Figures Figure No. Figure Title Page No. Figure 1: Saudi Arabia GDP, 2013-2019F (USD Billion) 6 Figure 2: Saudi Arabia Sector-wise Construction Spending Share, 2014 6 Figure 3: Saudi Arabia Thermal Insulation Market Size, By Value, 2011-2021F (USD Million) 13 Figure 4: Saudi Arabia Thermal Insulation Market Share, By Type, By Value, 2015 & 2021F 14 Figure 5: Saudi Arabia Electricity Consumption Share, By Sector, By Value, 2014 14 Figure 6: Saudi Arabia Thermal Insulation Market Share, By Application, By Value, 2015 & 2021F 15 Saudi Arabia District Cooling Market Size, By Value (USD Billion), By Volume (Million Figure 7: 17 TR), 2011-2021F Figure 8: Saudi Arabia District Cooling Market Share in GCC Region, By Value, 2015 18 Figure -

The Influence of Modern Social Media on Dermatologist Selection by Patients

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.11822 The Influence of Modern Social Media on Dermatologist Selection by Patients Mohammed Albeshri 1 , Ru'aa Alharithy 2 , Saad Altalhab 3 , Omar B. Alluhayyan 4 , Abdulrahman M. Farhat 5 1. Dermatology, Unaizah College of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Qassim University, Qassim, SAU 2. Dermatology, Security Forces Hospital, Riyadh, SAU 3. Dermatology, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud I University, Riyadh, SAU 4. Medicine, Unaizah College of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Qassim University, Qassim, SAU 5. Medicine, Sulaiman Al Rajhi University, Qassim, SAU Corresponding author: Mohammed Albeshri, [email protected] Abstract Objective Social media have become the platform of choice for people seeking immediate access to information. They have become so ubiquitous and pervasive that many people are using them to research health care providers and communicate with them about their issues. This study looks into this phenomenon, focusing on how it affects people’s thinking when deciding which doctor to see for skin-related concerns. Methodology A cross-sectional study was conducted among patients at Derma Clinic in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Data were collected using a validated self-administered questionnaire. A total of 365 patients were included in the analysis. Results Out of 365 participants, 44.9% visited the center for medical purposes, while 45.8% visited for cosmetic purposes. Sixty-six percent of the participants (n=241) went to a dermatologist they knew, and only 21% of those participants knew their dermatologist from social media (Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and Telegram). About 44.54% preferred to know more about their dermatologists from Twitter, followed by Instagram 27.96%, Snapchat 24.64%, and Facebook 2.84%. -

Ahmad Al Rahed Al Humaid Consulting Engineers HQ

Our International Projects Ahmad Al Rahed Al Humaid Consulting Engineers HQ مبنى فرح, شارع اﻷمير عبد الرحمن بن عبد العزيز – المربع ص.ب. 2193, الرياض 11451 – هاتف: 738 4029 11 +966 فاكس: 473 4029 11 +966 البريد اﻻلكتروني: [email protected] الموقع اﻻلكتروني: www.alsarif.com.sa AHMAD AL RASHED AL HUMAID – Consulting Engineers, (ARH) is one of the nation’s leading A/E firms specializing in planning and design of different types of construction works. ARH was established in 1978. The firm H.Q. is located in Riyadh, K.S.A. employing a multinational team of professionals whose expertise covers a multitude of engineering fields. ARH is an autonomous full service operator, organized to provide professional engineering services within the Kingdom, Middle East and Worldwide, undertaking variety of work in several countries such as Kazakhstan, Yemen, Tajikistan, Hong Kong, Bahrain, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Djibouti, Ahmad Al Rashed Al Humaid Guinea, Burkina Faso, Eritrea. ARH contributes to all phases of facility development and use. Starting with programming, planning and designing up to supervision stage during the construction of the project. Basic Architectural, Structural, Mechanical and Electrical Engineering services are complemented by the office’s architects and engineers and facility management divisions, which provide Architectural Design and Urban Studies, Interior Design and Decoration, Landscaping Design, Structural Design Study, Electrical Design Study, Mechanical Design Study, Roads and Highway Design Studies. ARH is committed to design engineering systems that meet today’s requirements while providing flexibility to accommodate the future technology. ARH had made collaboration with international firms to enhance its professional services, up-grade staff skills, performance and quality.