Bluestocking Feminism and British-German Cultural Transfer, 1750-1837

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

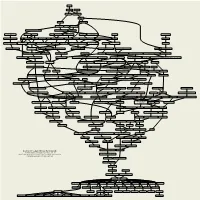

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’S Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ

Blackwell’s Rare Books Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Blackwell’S rare books Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/ rarebooks Our premises are in the main Blackwell bookstore at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest, as well as a large secondhand books department. There is lift access to each floor. The bookstore is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and close to several of the colleges and other university buildings, with on street parking close by. Oxford is at the centre of an excellent road and rail network, close to the London - Birmingham (M40) motorway and is served by a frequent train service from London (Paddington). Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Purchases: We are always keen to purchase books, whether single works or in quantity, and will be pleased to make arrangements to view them. Auction commissions: We attend a number of auction sales and will be happy to execute commissions on your behalf. Blackwell online bookshop www.blackwell.co.uk Our extensive online catalogue of new books caters for every speciality, with the latest releases and editor’s recommendations. -

Two Boys with a Bladder by Joseph Wright of Derby

RCEWA – Two Boys with a Bladder by Joseph Wright of Derby Statement of the Expert Adviser to the Secretary of State that the painting meets Waverley criteria two and three. Further Information The ‘Applicant’s statement’ and the ‘Note of Case History’ are available on the Arts Council Website: www.artscouncil.org.uk/reviewing-committee-case-hearings Please note that images and appendices referenced are not reproduced. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Brief Description of item(s) • What is it? A painting by Joseph Wright of Derby representing two boys in fancy dress and illuminated by candlelight, one of the boys is blowing a bladder as the other watches. • What is it made of? Oil paint on canvas • What are its measurements? 927 x 730 mm • Who is the artist/maker and what are their dates? Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797) • What date is the item? Probably 1768-70 • What condition is it in? Based upon a viewing of the work by the advisors and conservators, the face and costumes of the two boys are in good condition. However, dark paint throughout the background exhibits widespread retouched drying cracking and there are additional areas of clumsy reconstruction indicating underlying paint losses. 2. Context • Provenance In private ownership by the 1890s; thence by descent The early ownership of the picture, prior to the 1890s, is speculative and requires further investigation. The applicant has suggested one possible line of provenance, as detailed below. It has been mooted that this may be the painting referred to under a list of sold candlelight pictures in Wright’s account book as ‘Boys with a Bladder and its Companion to Ld. -

Joseph Wright

Made in Derby 2018 Profile Joseph Wright Derby’s most celebrated artist is known the world over. Derby Museums is home to the world’s largest collection of works by the 18th century artist. Joseph Wright of Derby is acknowledged officially as an “English landscape and portrait painter”. But his fame lies in being acclaimed as "the first professional painter to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution", by experts. Candlelight, the contrast of light and dark, known as the chiaroscuro effect, and the birth of science out of the previously held beliefs of alchemy all feature in his works. The inspiration for Wright’s work owes much to meetings of the Lunar Society, a group of scientists and industrialists living in the Midlands, which sought to reconcile science and religion during the Age of Enlightenment. Wright was born in Iron Gate – where a commemorative obelisk now stands –in 1734, the son of Derby’s town clerk John Wright. He headed to London in 1751 to study to become a painter under Thomas Hudson but returned in 1753 to Derby. Wright went back to London again for a further period of training before returning to set up his own business in 1757. He married, had six children – one of whom died in infancy, son John, died aged 17 but the others survived to live full lives. In 1773, he took a trip to Italy for almost two years and this became the inspiration for some of his work featuring Mount Vesuvius. Stopping off to work for a while in Bath as a portrait painter, he finally returned to Derby in 1777, where he remained until his death at 28 Queen Street in 1797. -

Darnley Portraits

DARNLEY FINE ART DARNLEY FINE ART PresentingPresenting anan Exhibition of of Portraits for Sale Portraits for Sale EXHIBITING A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS FOR SALE DATING FROM THE MID 16TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY On view for sale at 18 Milner Street CHELSEA, London, SW3 2PU tel: +44 (0) 1932 976206 www.darnleyfineart.com 3 4 CONTENTS Artist Title English School, (Mid 16th C.) Captain John Hyfield English School (Late 16th C.) A Merchant English School, (Early 17th C.) A Melancholic Gentleman English School, (Early 17th C.) A Lady Wearing a Garland of Roses Continental School, (Early 17th C.) A Gentleman with a Crossbow Winder Flemish School, (Early 17th C.) A Boy in a Black Tunic Gilbert Jackson A Girl Cornelius Johnson A Gentleman in a Slashed Black Doublet English School, (Mid 17th C.) A Naval Officer Mary Beale A Gentleman Circle of Mary Beale, Late 17th C.) A Gentleman Continental School, (Early 19th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Gerard van Honthorst, (Mid 17th C.) A Gentleman in Armour Circle of Pieter Harmensz Verelst, (Late 17th C.) A Young Man Hendrick van Somer St. Jerome Jacob Huysmans A Lady by a Fountain After Sir Peter Paul Rubens, (Late 17th C.) Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel After Sir Peter Lely, (Late 17th C.) The Duke and Duchess of York After Hans Holbein the Younger, (Early 17th to Mid 18th C.) William Warham Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller, (Early 18th C.) Head of a Gentleman English School, (Mid 18th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Hycinthe Rigaud, (Early 18th C.) A Gentleman in a Fur Hat Arthur Pond A Gentleman in a Blue Coat -

Carola Hilmes

CAROLA HILMES Georg Forster und Therese Huber: Eine Ehe in Briefen Vorblatt Publikation Erstpublikation Das literarische Paar. Le couple littéraire. Intertextualität der Geschlechterdiskurse. Intertextualité et discours des sexes, hrsg. von Gislinde Seybert, Bielefeld: Aisthesis 2003, S. 111–135. Neupublikation im Goethezeitportal Vorlage: Datei des Autors URL: <http://www.goethezeitportal.de/db/wiss/epoche/hilmes_forster_huber.pdf> Eingestellt am 21.01.2004 Autor PD Dr. Carola Hilmes Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Institut für Deutsche Sprache und Literatur II Postf. 11 19 32 60054 Frankfurt am Main Telefon: +49(69)798-32843 Emailadresse: [email protected] Empfohlene Zitierweise Beim Zitieren empfehlen wir hinter den Titel das Datum der Einstellung oder des letzten Updates und nach der URL-Angabe das Datum Ihres letzten Be- suchs dieser Online-Adresse anzugeben: Carola Hilmes: Georg Forster und Therese Huber: Eine Ehe in Briefen (12.01.2004). In: Goethezeitportal. URL: <http://www.goethezeitportal.de/db/wiss/epoche/hilmes_forster_huber.pdf> (Datum Ihres letzten Besuches). Hilmes: Georg Forster und Therese Huber, S.1 CAROLA HILMES Georg Forster und Therese Huber: Eine Ehe in Briefen „sei von meiner treuen Freundschaft überzeugt!“1 (Therese Forster an ihren Ehemann am 23. Januar 1788) „und sieh in mir einen Freund, der Dich immer zärtlich liebt“2 (Georg Forster an seine Ehefrau am 19. Juli 1793) 1) Die Ehe als literarische Produktionsgemeinschaft, S.3 2) Die kulturwissenschaftliche und mentalitätsgeschichtliche Relevanz der Korrespondenz, S.8 3) Die Asymmetrie der Überlieferung, S.20 Das überlieferte Bild einer unglücklichen Ehe, die Therese und Georg Forster geführt haben, ist korrekturbedürftig. Ihre Ehe ist nicht nur die Geschichte ei- ner gescheiterten Liebe, ihre Ehe ist auch die Geschichte wechselseitiger Aner- kennung und einer darauf gründenden außergewöhnlichen Freundschaft. -

ISECS Programm.Pdf

Congress Programme / Programme du congrès Last update: July 10 2015 The programme includes all registered participants Dernière mise à jour: 10 juillet 2015 Programme des participant/e/s inscrit/e/s 14th International Congress for Eighteenth-Century Studies Erasmus University Rotterdam, July 27-31, 2015 www.ISECS2015.com 10.07.2015 1 POSTER SESSION WEDNESDAY / MERCREDI, 29.07.2015 THURSDAY / JEUDI, 30.07.2015 Adam Smith on thE valuE of silvEr Presenter: Nohara, Shinji La réformE du dramE didErotiEn et lE projet dEs LumièrEs Presenter: Arndt de Santana, Christine Le Marché du livrE à la fin du XVIIIe sièclE: lE vécu dE Rétif dE la BrEtonnE Presenter: Claude, Klein Le texte épistolaire dans l’émergence d’un nouvel esprit à travers l’ Europe des Lumières Presenter: Kairova, Tetyana ThE PlacE of thE Local PoEt: Enacting thE GEnius Loci as ExpEriEntial Surface Presenter: Milne, Anne WomEn against slavEtradE Presenter: Veltman-van den Bos, Ans ThE SallEE RovErs and British Moral Economy Presenter: Ennis, Daniel 10.07.2015 2 PANELS MONDAY / LUNDI, 27.07.2015 KN305 (09:00 – 10:30, Room: M1-12: Oxford: Van Der Goot Building) OpEning CerEmony / KEynote 1: Space ExpandEd and FillEd Anew: Early ModErn Europe Keynote Speaker: Margaret Jacob Chair: Wijnand Mijnhardt S001(I) (11:00 - 12:30, Room: M1-09: BErgEn: Van Der Goot Building) ThE MarketplacE of REligion: EnlightenmEnt ThEologiEs and Prose Forms (I) Organizer / Chair: Sophie Gee, Sarah Rivett ñ Picciotto, Joanna: Methodism and the Novel. ñ Van Engen, Abram: Cultivation and Conversion: Sentimental Fiction on the Open Market. ñ Gee, Sophie: Communion, Communication and Sacrifice in Tom Jones. -

Derridean Deconstruction and Feminism

DERRIDEAN DECONSTRUCTION AND FEMINISM: Exploring Aporias in Feminist Theory and Practice Pam Papadelos Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry Adelaide University December 2006 Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................III DECLARATION .....................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................V INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 THESIS STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW......................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS – FEMINISM AND DECONSTRUCTION ............................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 FEMINIST CRITIQUES OF PHILOSOPHY..................................................................... 10 Is Philosophy Inherently Masculine? ................................................................ 11 The Discipline of Philosophy Does Not Acknowledge Feminist Theories......... 13 The Concept of a Feminist Philosopher is Contradictory Given the Basic Premises of Philosophy..................................................................................... -

The Birth of Chinese Feminism Columbia & Ko, Eds

& liu e-yin zHen (1886–1920?) was a theo- ko Hrist who figured centrally in the birth , karl of Chinese feminism. Unlike her contem- , poraries, she was concerned less with China’s eds fate as a nation and more with the relation- . , ship among patriarchy, imperialism, capi- talism, and gender subjugation as global historical problems. This volume, the first translation and study of He-Yin’s work in English, critically reconstructs early twenti- eth-century Chinese feminist thought in a transnational context by juxtaposing He-Yin The Bir Zhen’s writing against works by two better- known male interlocutors of her time. The editors begin with a detailed analysis of He-Yin Zhen’s life and thought. They then present annotated translations of six of her major essays, as well as two foundational “The Birth of Chinese Feminism not only sheds light T on the unique vision of a remarkable turn-of- tracts by her male contemporaries, Jin h of Chinese the century radical thinker but also, in so Tianhe (1874–1947) and Liang Qichao doing, provides a fresh lens through which to (1873–1929), to which He-Yin’s work examine one of the most fascinating and com- responds and with which it engages. Jin, a poet and educator, and Liang, a philosopher e plex junctures in modern Chinese history.” Theory in Transnational ssential Texts Amy— Dooling, author of Women’s Literary and journalist, understood feminism as a Feminism in Twentieth-Century China paternalistic cause that liberals like them- selves should defend. He-Yin presents an “This magnificent volume opens up a past and alternative conception that draws upon anar- conjures a future. -

Canadian Woman Studies Feminist Journalism Ies Cahiers De La Femme

Feminist Collections A Quarterly of Women's Studies Resources Volume 18, No.4, Summer 1997 CONTENTS From the Editors Book Reviews The Hearts and Voices of Midwestern Prairie Women by Barbara Handy-Marchello Not Just White and Protestant: Midwestern Jewish Women by Susan Sessions Rugh Beyond Bars and Beds: Thriving Midwestern Queer Culture by Meg Kavanaugh Multiple Voices: Rewriting the West by Mary Neth The Many Meanings of Difference by Mary Murphy Riding Roughshod or Forging New Trails? Two Recent Works in Western U.S. Women's History by Katherine Benton Feminist Visions Flipping the Coin of Conquest: Ecofeminism and Paradigm Shifts by Deb Hoskins Feminist Publishing World Wide Web Review: Eating Disorders on the Web by Lucy Serpell Computer Talk Compiled by Linda Shult New Reference Works in Women's Studies Reviewed by Phyllis Holman Weisbard and others Periodical Notes Compiled by Linda Shult Items of Note Compiled by Amy Naughton Books Recently Received Supplement: Index to Volume 18 FROMTHE EDITORS: About the time we were noticing a lot of new book titles corning out about the history of women in the U.S. West and Midwest, a local planning committee for University of Wisconsin-Extension was starting to pull together a conference focusing on Midwest women's history. That conference took place in early June and included some really exciting research. There were sessions on the interactionslcultural exchange between missionary women and Dakota women in the Minnesota area; Illinois women in the legal profession around 1869; violations of class, race, and gender expectations by prostitutes in Mis- souri, Catholic Sisters teaching in public schools in 19th-century Wisconsin; Midwestern women's clubs; Hmong women's history and culture in the Mid- west; Twin Cities working women in the early 20th century; the world of Harriet and Dred Scott; and so much more territory was covered in this two-day get- together. -

Biblioteks Historie 7

DANSK BIBLIOTEKSHISTORISK SELSKAB BIBLIOTEKS HISTORIE 7 KØBENHAVN 2005 Bibliotekshistorie 7 Udgivet af Dansk Bibliotekshistorisk Selskab Redaktion: Steen Bille Larsen under medvirken af Ole Harbo Jørgen Svane-Mikkelsen © Dansk Bibliotekshistorisk Selskab 2005 ISSN 0109-923X Sats og tryk Handy-Print A/S, Skive Indhold Universitetsbiblioteket i Göttingen, oplysningstidens mønsterbibliotek En beskrivelse af dets udvikling i pionertiden Af Sigrid Schacht 5 Bibliotekstilbud i København før de kommunale folkebiblioteker Lejebiblioteker, klub- og foreningsbiblioteker samt folkebiblioteker ca. 1850-1885 Af Kirsten Mosolff 25 "Bibliotekssagen trænger til Organisation" Folkebibliotekerne i Danmark 1880-1920 Af Laura Skouvig 73 Tre efterreformatoriske katolske biblioteker i København indtil 1962 Af Helge Clausen 110 "Biblioteket som musikkens skatkammer" Aspekter på et bibliotekarisk uddannelsesforløb Af Bent Christiansen 170 Dansk Bibliotekshistorisk Selskab Styrelsens beretning 2002-2003 199 Universitetsbiblioteket i Göttingen, oplysningstidens mønsterbibliotek En beskrivelse af dets udvikling i pionertiden Af Sigrid Schackt Universitetsinstitutionens grundlæggelse Grundlæggeren af Göttingens Universitet, kong Georg 2. af England, var født kurfyrste af Hannover. Den engelske trone arve- de han efter sin far, der som den første hannoveraner blev britisk re- gent. Personalunionen mellem Hannover og Storbritannien varede fra 1714-1837. Da Georg 2. i 1733 udstedte en forordning om op- rettelse af et universitet i sit tyske kurfyrstendømme, lagde han -

Johann Joachim Eschenburg

BRAUNSCHWEIGER WERKSTüCKE Veröffentlichungen aus Archiv, Bibliothek und Museum der Stadt Herausgegeben von Ben Bilzer und Richard Moderhack Band 20 ]OHANN ]OACHIM ESCHENBURG 1743-1820 Professor am Collegium Carolinum zu Braunschweig Kurzer Abriß seines Lebens und Schaffens nebst Bibliographie von FRITZ MEYEN 1957 WAISENHAUS-BUCHDRUCKEREI UND VERLAG BRAUNSCHWEIG VORWORT Der Plan, eine Bibliographie der Veröffentlichungen JOHANN JOACHIM ESCHENBURGS zusammenzustellen, entstand während der Materialsammlung zu einer 1952 erschienenen kleinen Schrift »Aus der Geschichte der Bibliotheca Collegii Carolini (1748-1835)". Fünf Professoren hatten während der Berichtszeit die Bibliothek des Collegium Caro linum verwaltet, deren Bestände noch heute zu den Kostbarkeiten der von mir geleiteten Bibliothek der Technischen Hochschule Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig gehören. Vier dieser Professoren-Bibliothekare sind nicht sonderlich hervorgetreten, so daß es einige Mühe kostete, wenigstens die wichtigsten biographischen Daten zu ermitteln. Einer von ihnen aber, nämlich JOHANN JOACHIM ESCHENBURG, der von 1782 bis 1820 das Amt des Bibliothekars neben dem Ordinariat für Literaturwissenschaft innehatte, ist auch heute noch in der Geistesgeschichteein Begriff. Bei Durchsicht der nicht sehr zahlreichen Veröffentlichungen, die ESCHENBURG einen besonderen Abschnitt widmen, stellte sich heraus, daß entweder nur ein e Seite seines Wirkens beleuchtet wurde: seine Stellung zur englischen Literatur, insbesondere seine SHAKEsPEARE-übersetzung, seine Gedichte und Bearbeitungen