Christian Gottlob Heyne and the Changing Fortunes of the Commentary in the Age of Altertumswissenschaft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

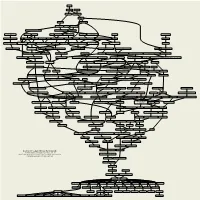

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’S Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ

Blackwell’s Rare Books Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Blackwell’S rare books Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/ rarebooks Our premises are in the main Blackwell bookstore at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest, as well as a large secondhand books department. There is lift access to each floor. The bookstore is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and close to several of the colleges and other university buildings, with on street parking close by. Oxford is at the centre of an excellent road and rail network, close to the London - Birmingham (M40) motorway and is served by a frequent train service from London (Paddington). Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Purchases: We are always keen to purchase books, whether single works or in quantity, and will be pleased to make arrangements to view them. Auction commissions: We attend a number of auction sales and will be happy to execute commissions on your behalf. Blackwell online bookshop www.blackwell.co.uk Our extensive online catalogue of new books caters for every speciality, with the latest releases and editor’s recommendations. -

University of Groningen Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Bremmer

University of Groningen Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Bremmer, J.N. Published in: Griechische Mythologie und Frühchristentum IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N. (2005). Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece: Observations on a Difficult Relationship. In R. von Haehling (Ed.), Griechische Mythologie und Frühchristentum (pp. 21-43). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 N. Oettinger, ‘Entstehung von Mythos aus Ritual. Das Beispiel des hethitischen textes CTH 390A’, in M. Hutter and S. Hutter-Braunsar (eds), Offizielle Religion, lokale Kulte und individuelle Religiosität (Münster, 2004) 347-56. MYTH AND RITUAL IN ANCIENT GREECE: OBSERVATIONS ON A DIFFICULT RELATIONSHIP by JAN N. -

00 Portadillas

La primera Historia de la Literatura romana: el programa de curso de F. A. Wolf (1787) 1 Francisco GarCía -J UradO Bernd MarIzzI Universidad Complutense [email protected] [email protected] recibido: 31 de marzo de 2009 aceptado: 20 de octubre de 2009 RESUMEN Se ofrece por primera vez en versión castellana el programa de Historia de la Literatura romana publi - cado por Friedrich august Wolf en 1787. El programa, escrito originalmente en alemán (y no en latín, como era normal en este tipo de publicaciones), contiene la primera formulación de una historia litera - ria en términos de literatura nacional. asimismo, se hace un estudio biográfico del autor y de su im - pronta en España, al tiempo que se ofrece un comentario de las ideas historiográficas que sustentan el curso, no ajenas a la estética del llamado Clasicismo de Weimar. Palabras clave: Historia literaria. Literatura romana. Friedrich august Wolf. GarCía -J UradO , F., MarIzzI , B., «La primera Historia de la Literatura romana: el programa de curso de F. a. Wolf (1787)», Cuad. fil. clás. Estud. Lat . 29.2 (2009) 145-177. The first History of roman Literature: F. a. Wolf’s lecture programme (1787) AbStRAct This is the first time F. a. Wolf’s History of roman Literature Programme is translated to Spanish since its first edition in 1787. The programme is written in German (not in Latin, as it was usual in this kind of studies), and roman Literature is shown as a national literature. In addition, we study Wolf’s life, his influence in Spain and we offer a commentary on historiographic ideas found in his programme. -

Vivariumnovum

Accademia VivariumNovum Accademia VivariumNovum Our roots The present Future plans INDEX THE ACADEMY IN BRIEF 2 1. A school for talent 5 2. An authentic Res publica litterarum 7 3. Why we speak in Latin and Greek? 9 4. Conversing with the past 11 5. Mens sana in corpore sano 13 6. Where the humanities have no price 15 OUR ROOTS 18 1. The roots of the academy 21 2. The birth of a project 23 3. A bucolic location 25 4. Major conferences and famous scholars 27 5. Major international conferences 29 Notes: International conferences 30 THE ACADEMY TODAY 36 1. The present roman campus 39 PROFUSUM 2. The principal activity of the Academy 41 3. Musical activities and classical poetry 43 SAPIENTIAE 4. Excursions and on-site lessons 45 5. Hosting schools 47 SEMEN 6. Forming teachers in a living method 49 IUSTITIAE 7. Intensive summer language courses 51 8. Our programme: research and study 53 ALERE Notes: Curriculum of studies 54 Notes: Reading list 58 FLAMMA 9. The publishing house: didactic and research 61 10. Two journals: Mercurius and Ianus 63 11. A library for the study of the humanities 65 12. Collaborations and affiliations 67 Notes: Alumni of the Academy 68 Notes: Visiting professors 72 Notes: An appeal to Unesco 76 FUTURE PROJECTS 80 1. A new campus for the humanities 83 Notes: An ideal campus 84 2. Universities and historical sites 87 3. Archeological study camps 89 4. Virtual reality and audio-visual projects 91 5. Distance learning programmes 93 6. Latin and the sciences 95 7. -

Peripatetics Between Ethics, Comedy and Rhetoric

DISSERTATIONES STUDIORUM GRAECORUM ET LATINORUM UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 4 DISSERTATIONES STUDIORUM GRAECORUM ET LATINORUM UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 4 CHARACTER DESCRIPTION AND INVECTIVE: PERIPATETICS BETWEEN ETHICS, COMEDY AND RHETORIC IVO VOLT Department of Classical Philology, Institute of Germanic, Romance and Slavonic Languages and Literatures, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Tartu, Estonia The Council of the Institute of Germanic, Romance and Slavonic Lan- guages and Literatures has, on 31 August 2007, accepted this disser- tation to be defended for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Philology. Supervisor: Professor Anne Lill, University of Tartu Reviewer: Professor Karin Blomqvist, University of Lund The dissertation will be defended in Room 209, Ülikooli 17, on 21 De- cember 2007. The publication of the dissertation was funded by the Institute of Ger- manic, Romance and Slavonic Languages and Literatures, University of Tartu. ISSN 1406–8192 ISBN 978–9949–11–793–2 (trükis) ISBN 978–9949–11–794–9 (PDF) Autoriõigus Ivo Volt, 2007 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus www.tyk.ee Tellimus nr. 528 PREFACE This thesis has originated from my interest in the Characters of Theophras- tos, a remarkable piece of writing from the Greek antiquity and a true aureolus libellus.1 I first read the Characters, in Russian, for a Russian class during my first year of study at the University of Tartu in 1993, and since then have come across this work several times, including a course on the Characters by Anne Lill in 1996, my B.A. and M.A. theses (1997 and 2000), a course on the Characters by myself (1999), and the Estonian translation and commentary of the work (Lill & Volt 2000). -

The Limits of Communication Between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns

Body Language: The Limits of Communication between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns. Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bridget Susan Buchholz, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Sarah Iles Johnston Fritz Graf Carolina López-Ruiz Copyright by Bridget Susan Buchholz 2009 Abstract This project explores issues of communication as represented in the Homeric Hymns. Drawing on a cognitive model, which provides certain parameters and expectations for the representations of the gods, in particular, for the physical representations their bodies, I examine the anthropomorphic representation of the gods. I show how the narratives of the Homeric Hymns represent communication as based upon false assumptions between the mortals and immortals about the body. I argue that two methods are used to create and maintain the commonality between mortal bodies and immortal bodies; the allocation of skills among many gods and the transference of displays of power to tools used by the gods. However, despite these techniques, the texts represent communication based upon assumptions about the body as unsuccessful. Next, I analyze the instances in which the assumed body of the god is recognized by mortals, within a narrative. This recognition is not based upon physical attributes, but upon the spoken self identification by the god. Finally, I demonstrate how successful communication occurs, within the text, after the god has been recognized. Successful communication is represented as occurring in the presence of ritual references. -

JOHANN AUGUST ERNESTI: the ROLE of HISTORY in BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION John H. Sailhamer* I. Introduction

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 193–206 JOHANN AUGUST ERNESTI: THE ROLE OF HISTORY IN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION john h. sailhamer* i. introduction This article will address the question regarding the role of history in Bib- lical interpretation. It will do so within the context of an evangelical view of Scripture. By this I mean a view that holds the Bible to be the inspired locus of divine revelation. There are, of course, other approaches to Scripture and hermeneutics. There are probably also other definitions of the evangelical view of Scripture; but I think the view I have described is the classical view that is rooted in classical orthodoxy and the Reformation creeds. My primary interest in the subject of this article is and has been in the hermeneutics of the OT. The literature and historical situation of the com- position of the OT and the NT are different enough to caution against a fac- ile application of the same hermeneutical principles to both. Nevertheless, I believe that the same principles do apply to both, but each in terms of its own specific issues and questions. In this article I will approach the question of the role of history in Bib- lical interpretation from the point of view of the history of interpretation. I have elsewhere given a lengthy theoretical discussion of the issue.1 There I argued that history, and especially the discipline of philology (the study of ancient texts), should play a central role in our understanding about the Biblical texts. Who was the author? When was a book written? Why was it written? What is the lexical meaning of its individual words? History also plays a central role in the apologetic task of defending the historical verac- ity of the Biblical record. -

Golyzniak Zu Wagner Boardman

Diana SCARISBRICK – Claudia WAGNER – John BOARDMAN, The Beverly Collec- tion of Gems at Alnwick Castle. The Philip Wilson Gems and Jewellery Series Bd. 2. London/New York: Philip Wilson Publishers 2016, 320 S., 480 farb. Abb. Since the 18th century the ancient Percy family, earls of Northumberland has been collecting engraved gems. Their assemblage is presently housed at Alnwick Castle. Traditionally referred as the Beverly Gems,1 now they are published in a fabulous book prepared by the top researchers in the field of glyptics: Diana Sca- risbrick, Claudia Wagner, and Sir John Boardman from the Beazley Archive, Oxford.2 Their new volume is a sizable and richly illustrated book that for sure will be of much interest to archaeologists, art historians, and all people interes- ted in gem engraving and the history of collecting. The book starts with a short preface outlining the basic scope and history of the project embarked on by the Oxford researchers (p. vii). This is followed by a list of the abbreviations that are used in the book, including essential guidance to the catalogue entries (pp. viii-xiii). Next, the history of the collection is pre- sented (pp. xv-xxv). This section, deeply researched and fully referenced to the archival material, is written in an approachable way by Diana Scarisbrick. The conclusion to the first part includes commentary on the records of the Beverly Gems and casts as well as the previous scholarship devoted to them.3 While the merit of earlier works should not be diminished, it is only with the present book authored by the Oxford researchers that we have a thorough study of the who- le collection. -

Diodoros of Sicily

STUDIA HELLENISTICA 58 DIODOROS OF SICILY HISTORIOGRAPHICAL THEORY AND PRACTICE IN THE BIBLIOTHEKE edited by Lisa Irene HAU, Alexander MEEUS, and Brian SHERIDAN PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - BRISTOL, CT 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................. IX SETTING THE SCENE Introduction ......................................... 3 Lisa Irene HAU, Alexander MEEUS & Brian SHERIDAN New and Old Approaches to Diodoros: Can They Be Reconciled? 13 Catherine RUBINCAM DIODOROS IN THE FIRST CENTURY Diodoros of Sicily and the Hellenistic Mind ................ 43 Kenneth S. SACKS The Origins of Rome in the Bibliotheke of Diodoros .......... 65 Aude COHEN-SKALLI In Praise of Pompeius: Re-reading the Bibliotheke Historike..... 91 Richard WESTALL GENRE AND PURPOSE From Ἱστορίαι to Βιβλιοθήκη and Ἱστορικὰ Ὑπομνήματα . 131 Johannes ENGELS History’s Aims and Audience in the Proem to Diodoros’ Bibliotheke 149 Alexander MEEUS A Monograph on Alexander the Great within a Universal History: Diodoros Book XVII ................................... 175 Luisa PRANDI VI TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW QUELLENFORSCHUNG Errors and Doublets: Reconstructing Ephoros and Appreciating Diodoros ........................................... 189 Victor PARKER A Question of Sources: Diodoros and Herodotos on the River Nile ............................................... 207 Jessica PRIESTLEY Diodoros’ Narrative of the First Sicilian Slave Revolt (c. 140/35- 132 B.C.) – a Reflection of Poseidonios’ Ideas and Style? ....... 221 Piotr WOZNICZKA How to Read a Diodoros Fragment ....................... 247 Liv Mariah YARROW COMPOSITION AND NARRATIVE Narrator and Narratorial Persona in Diodoros’ Bibliotheke (and their Implications for the Tradition of Greek Historiography)... 277 Lisa Irene HAU Ring Composition in Diodoros of Sicily’s Account of the Lamian War (XVIII 8–18) ..................................... 303 John WALSH Terminology of Political Collaboration and Opposition in Dio- doros XI-XX ....................................... -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SMATHERS LIBRARIES’ LATIN AND GREEK RARE BOOKS COLLECTION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LECTORI: TO THE READER ........................................................................................ 20 LATIN AUTHORS.......................................................................................................... 24 Ammianus ............................................................................................................... 24 Title: Rerum gestarum quae extant, libri XIV-XXXI. What exists of the Histories, books 14-31. ................................................................................. 24 Apuleius .................................................................................................................. 24 Title: Opera. Works. ......................................................................................... 24 Title: L. Apuleii Madaurensis Opera omnia quae exstant. All works of L. Apuleius of Madaurus which are extant. ....................................................... 25 See also PA6207 .A2 1825a ............................................................................ 26 Augustine ................................................................................................................ 26 Title: De Civitate Dei Libri XXII. 22 Books about the City of God. ..................... 26 Title: Commentarii in Omnes Divi Pauli Epistolas. Commentary on All the Letters of Saint Paul. .................................................................................... -

9. Gundolf's Romanticism

https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2021 Roger Paulin This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Roger Paulin, From Goethe to Gundolf: Essays on German Literature and Culture. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2021, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258#copyright Further details about CC-BY licenses are available at, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Updated digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. ISBN Paperback: 9781800642126 ISBN Hardback: 9781800642133 ISBN Digital (PDF): 9781800642140 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 9781800642157 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9781800642164 ISBN Digital (XML): 9781800642171 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0258 Cover photo and design by Andrew Corbett, CC-BY 4.0.