49086-001: Upper Trishuli 1 Hydroelectric Power Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Damage Mapping of April 2015 Nepal Earthquake Using Small

J-Rapid Final Workshop 21 June, 2016, Kathmandu Inventory mapping of landslides induced by the Gorkha earthquake 2015 and a proposal for hazard mapping of future landslides for making a plan of better reconstruction "Impact on infrastructure by Gorkha earthquake 2015 induced landslides" Masahiro CHIGIRA Masahiro CHIGIRA Professor, Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Professor, Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University Kyoto University Vishnu DANGOL Vishnu DANGOL Professor, Department of Geology, Professor, Department of Geology, Tribhuvan University Tribhuvan University Objective 1. to make an inventory mapping on landslides, cracks, and landslide dams induced by the Nepal earthquake and to investigate their formative mechanisms 2. to detect displaced areas of slope surfaces, of which future susceptibility to landslides would be evaluated on the basis of geology, geomorphology, and groundwater conditions. 3. propose a methodology of hazard mapping for earthquake-induced landslides in Nepal. Members (Japan side) 1. Masahiro CHIGIRA (Kyoto Univ.) PI Applied Geology 2. Daisuke HIGAKI (Hirosaki Univ.) Landslide control 3. Hiroshi YAGI (Yamagata Univ.) Landslide susceptibility mapping 4. Akihiko WAKAI (Gunma Univ.) Geotechnical analysis of landslide 5. Hiroshi, P. SATO (Nihon Univ.) Remote sensing 6. Go, SATO (Teikyo Heisei Univ.) Geomorphology 7. Ching-Ying, TSOU (Hirosaki Univ.) GIS analysis 8. Akiyo YATAGAI (Res. Inst. Humanity and Nature) Meteorology Members (Nepali side) 1. Vishnu DANGOL (Tribhuvan Univ.) PI Applied Geology 2. Smajwal BAJRACHARYA (ICIMOD) Remote sensing 3. Shanmukhesh Chandra AMATYA (DWIDP) Hydrogeology 4. Tuk Lal ADHIKARI (ITECO-Nepal) Geotechnical Field survey • Trishuli River catchment from Trishuli to Syabrubesi (29 October to 1 November, 2015) • Sun Kosi and Bhote Kosi River catchments from Bansaghu to Kodari. -

Article of a Given In- with Postdepositional Erosion

Earth Surf. Dynam., 8, 769–787, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-8-769-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Timing of exotic, far-traveled boulder emplacement and paleo-outburst flooding in the central Himalayas Marius L. Huber1,a, Maarten Lupker1, Sean F. Gallen2, Marcus Christl3, and Ananta P. Gajurel4 1Geological Institute, Department of Earth Sciences, ETH Zurich, Zurich 8092, Switzerland 2Department of Geosciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, USA 3Laboratory of Ion Beam Physics (LIP), Department of Physics, ETH Zurich, Zurich 8093, Switzerland 4Department of Geology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal acurrent address: Université de Lorraine, CNRS, CRPG, 54000 Nancy, France Correspondence: Marius L. Huber ([email protected]) Received: 28 February 2020 – Discussion started: 20 March 2020 Revised: 21 July 2020 – Accepted: 11 August 2020 – Published: 22 September 2020 Abstract. Large boulders, ca. 10 m in diameter or more, commonly linger in Himalayan river channels. In many cases, their lithology is consistent with source areas located more than 10 km upstream, suggesting long trans- port distances. The mechanisms and timing of “exotic” boulder emplacement are poorly constrained, but their presence hints at processes that are relevant for landscape evolution and geohazard assessments in mountainous regions. We surveyed river reaches of the Trishuli and Sunkoshi, two trans-Himalayan rivers in central Nepal, to improve our understanding of the processes responsible for exotic boulder transport and the timing of em- placement. Boulder size and channel hydraulic geometry were used to constrain paleo-flood discharge assuming turbulent, Newtonian fluid flow conditions, and boulder exposure ages were determined using cosmogenic nu- clide exposure dating. -

Nepal Earthquake District Profile - Rasuwa OSOCC Assessment Cell 10.05.2015

Nepal Earthquake District Profile - Rasuwa OSOCC Assessment Cell 10.05.2015 This report is produced by the OSOCC Assessment Cell based on secondary data from multiple sources, including the Government of Nepal, UNDAC, United Nations Agencies, non-governmental organisation and media sources. I. Situation Overview Rasuwa is one of the worst affected districts by the 25 April earthquake. As of 8 May, 430 people have been reported killed and 753 injured (MoFA 08/05/2015). Most of those that died in the district were killed in an avalanche that buried inhabtants of Langtang village including tourists in the guesthouses. Some remote areas are yet to be reached or accounted for. More than 63% of the district’s territory is at an elevation of more than 3000 meters. Of the remaining territory, most parts are located at an elevation between 1000 – 3000 meters (University of Copenhagen 2005) and parts of Rasuwa were without road access even before the earthquake, further challenging the relief effort. In the first few days after the earthquake very little information was available from Rasuwa. Field reports have gradually come in that help understand thesituation. Initial estimates based on Government data of damaged buildings in the affected districts, suggests that 82% of the population of Rasuwa have been affected by the earthquake. According to Government data, 8,000 buildings were destroyed in the earthquake. This figure is however unconfirmed and represents a preliminary estimate based on the combination of reports from a range of sources providing information on needs at the VDC level1(Please see map below for an illustration of aggregated number of reported people in need). -

EDUCATION, AWARENESS and FACING DEVELOPMENT in RASUWA Ariel Murray SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2018 MONEY SPEAKS: EDUCATION, AWARENESS AND FACING DEVELOPMENT IN RASUWA Ariel Murray SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Educational Sociology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Tourism Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Murray, Ariel, "MONEY SPEAKS: EDUCATION, AWARENESS AND FACING DEVELOPMENT IN RASUWA" (2018). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2860. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2860 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONEY SPEAKS: EDUCATION, AWARENESS AND FACING DEVELOPMENT IN RASUWA By Ariel Murray (Fig. 1: three of the six hotels in Nagathali, Thuman Ward 6, Rasuwa) Academic Director: Onians, Isabelle Project Advisor: Dixit, Kunda Sending School: Smith College Major: Government Studies; French Studies Primary Research Location(s): Asia, Nepal, Rasuwa, Thuman, Nagathali, Brenthang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Nepal: Tibetan and Himalayan Peoples, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2018 Abstract In the Rasuwa district of Nepal, an area affected profoundly by the 2015 earthquake, development and infrastructure have been fast growing both since the natural disaster and the opening of Rasuwa Gadhi as the more formal trade route to and from China. -

NEPAL Earthquake ECHO CRISIS FLASH No

NEPAL Earthquake ECHO CRISIS FLASH No. 10 shortage Period covered 1. Map 25 April – 4 May 2015 Time of validity 18:00 (Kathmandu) – 12:15 (UTC) ECHO Field Office New Delhi – INDIA Number of dead (Government of Nepal): 7 276 Number of wounded (Government of Nepal): 14 362 2. Situation The death toll resulting from the earthquake which struck central Nepal on 25 April has risen to 7 276, with 14 362 injured (Government of Nepal-GoN figures, 4 May). It is anticipated that these figures will further increase as remote areas are becoming accessible for government officials and humanitarian actors. On 3 May, the GoN declared the USAR (Urban Search and Rescue) phase over; it is now paramount that the emergency humanitarian response is further scaled up to reach remote and most affected Village Development Committees (VDCs), ensuring speedy movement and delivery of relief items. According to UN estimates, up to 8 million people have been affected by the ECHO Emergency Contact earthquake. Over 54% of the deaths have been recorded in the districts of Tel.: +32 2 29 21112 Sindhupalchowk and Kathmandu, but there remain entire districts, such as Fax: +32 2 29 86651 Rasuwa, which have yet to be accessed. Approximately 2.8 million people are [email protected] believed to have been temporarily displaced from their homes (USAID Factsheet 7), though numbers are decreasing as people return home in the ECHO Crisis Flash No. 10 – NEPAL Earthquake Kathmandu Valley or are moving from there to their rural districts of origin. Over 10 700 houses have been reported destroyed, with over 14 700 damaged; the GoN estimates that over 200 000 houses have been destroyed and more than 188 000 damaged (GoN, 3 May). -

Security and Justice from a District Perspective Rasuwa, Nepal

Snapshot series 1 Security and justice from a district perspective Rasuwa, Nepal November 2010 Understanding conflict. Building peace. About International Alert International Alert is an independent peacebuilding organisation that has worked for over 20 years to lay the foundations for lasting peace and security in communities affected by violent conflict. Our multifaceted approach focuses both in and across various regions; aiming to shape policies and practices that affect peacebuilding; and helping build skills and capacity through training. Our field work is based in Africa, South Asia, the South Caucasus, Latin America, Lebanon and the Philippines. Our thematic projects work at local, regional and international levels, focusing on cross- cutting issues critical to building sustainable peace. These include business and economy, gender, governance, aid, security and justice. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding NGOs with more than 125 staff based in London and our 13 field offices. To learn more, visit www.international-alert.org. © International Alert 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. Front cover image: Babita Basnet International Alert Briefing Paper Snapshot series 1 Security and justice from a district perspective Rasuwa, Nepal 2 International Alert Author Profile Bhasker Kafle Bhasker Kafle is Senior Programme Officer for International Alert in Nepal. Currently, he is involved in International Alert’s work with youth on public security challenges and responses in Nepal. His work includes leading training, research and advocacy initiatives in the districts and in Kathmandu on justice and security issues. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Nepal Earthquake: One Year On

ne year has passed since a devastating magnitude-7.8 earthquake struck Nepal on 25 April 2015, with the epicenter about 80 kilometers northwest of the capital, Kathmandu. This was the worst disaster to hit Nepal in decades. Only 17 days later a second earthquake of magnitude 7.4 hit near Mount Everest, taking more lives and destroying more homes. According to government estimates, the earthquakes EXECUTIVE Oleft over 750,000 houses and buildings destroyed or damaged and caused over 8,790 deaths. It is estimated that the earthquakes affected the lives of approximately eight million people, constituting almost one-third of the population of Nepal. With the situation dire, the Nepal government declared a state of emergency, and appealed for international aid. Along with other agencies, Habitat SUMMARY for Humanity answered the call to assist the people of Nepal. During the emergency phase, Habitat distributed 5,142 temporary shelter kits to families whose homes were destroyed or left uninhabitable. Habitat volunteers removed 650 tons of earthquake rubble, and distributed 20,000 water backpacks to families in earthquake-affected areas. As the emergency phase ended, Habitat’s programs shifted into reconstruction. Engineers completed safety assessments on 16,244 earthquake- damaged homes. Initial construction began on permanent homes in the community in Kavre district. As months passed, winter brought the threat of cold weather exposure, and Habitat distributed 2,424 winterization kits to families at risk to the elements. In addition, 32 trainers and 632 people in affected communities received instruction on the Participatory Approach for Safe Shelter Awareness. Overall in the first year since the earthquakes, Habitat for Humanity provided assistance to more than 43,700 families through various disaster response programs. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

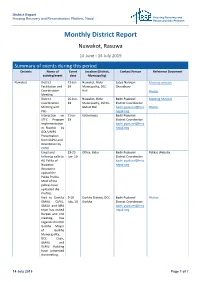

Monthly District Report

District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform Monthly District Report Nuwakot, Rasuwa 14 June - 14 July 2019 Summary of events during this period Districts Name of Event Location (District, Contact Person Reference Document activity/event date Municipality) Nuwakot District 12-Jul- Nuwakot, Bidur Satya Narayan Meeting minutes Facilitation and 19 Municipality, DCC Chaudhary Coordination Hall Photos Meeting District 26-Jun- Nuwakot, Bidur Badri Pyakurel Meeting Minutes Coordination 19 Municipality, DLPIU- District Coordinator Meeting with GMaLI Hall badri.pyakurel@hrrp Photos POs nepal.oeg Interaction on 7 Jun- Kathmandu Badri Pyakurel STFC Program 19 District Coordinator implementation badri.pyakurel@hrrp in Nwakot by nepal.oeg GOI/UNIPS Presentation from DLPIU and Orientation by CLPIU. Email and 19-25 Office, Bidur Badri Pyakurel Palikas Website followup calls to Jun- 19 District Coordinator ALl Palika of badri.pyakurel@hrrp Nuwakot nepal.oeg Rasuwa to upload the Palika Profile. Most of the palikas have uploaded the Profiles. Visit to GorKha 9-10 Gorkha District, DCC Badri Pyakurel Photos GMALI. CLPIU, July, 19 Gorkha District Coordinator GMALI and NRA badri.pyakurel@hrrp team has visited nepal.oeg Barpak and one meeting has organized in DCC Gorkha. Mayor of Gorkha Munucipality, DCC Chair, GMALI and DLPIU Building have presented the meeting. 14 July 2019 Page 1 of 7 District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform Summary of events during this period Rasuwa Joint Monitoring 20/21- Rasuwa, Uttargaya Badri Pyakurel Field Visit with Jun-19 Rural municipality, District Coordinator CLPIU/DLPIU Ward 1,2 badri.pyakurel@hrrp building nepal.oeg Follow up calls and 23-25 Badri Pyakurel Emails mails to upload Jun, 19 District Coordinator palika profile . -

Rasuwa (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Rasuwa (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 43,3001 18 VDCs Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Rasuwa National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 87% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 10% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 12,024 Other 3% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 620 % of households who own 90% 85% Total 12,6442 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. Out of 1,406 Grievances listed 1,287 were addressed as eligible for Rasuwa District. NRA Rasuwa already circulated details to all respective rural municipality and ward level offices. 2. Batash Foundation has completed 151 houses to its beneficiaries at Yarsa VDC ward 5. Formalhandover program has not been scheduled yet. 3. 37 HHs from Thulogoun VDCs of Rasuwa district have received third tranche of govern- ment subsid with financial and technical support from Nepal Red Cross society /Build Change. HRRP Rasuwa HRRP © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) ACF LACCOS 838 25 DEPROCS SHORT TRAINING GIZ GOAL VOCATIONAL TRAINING 300 901 GOAL UON (Targets Achieved) HELVETAS GMTI,CMES Reached Remaining KF LDF LUMANTI 72 Demonstration Constructions in 10 VDCs LWF MANEKOR,BATAS NAF NRCS OM-N 8 VDCs with Household WASH Assistance PPY SAHAS SP OM-N 9,682 beneficiaries enrolled, 86% 15 partners 4 This table indicates the partner organisations and 9,456 beneficiaries received the 1st Tranche, 84% their respective implementing partner(s) KEY CONTACTS DAO OFFICE DDC OFFICE NRA District Office DUDBC OFFICE Mr. -

Download Brochure

Nepal Hidden Treks & Expedition P. Ltd Tamang Heritange Trek Introduction Tamang heritage trek starts from Syabrubesi (1460m) and passes through Gatlang, Chilime, Thuman, Timure and Briddim tamang villlage.The people of this region are mostly Tibetans who came from Kerung in Tibet across the border and settled in Nepal. In earlier days, the citizenship of Nepal would not be offered to real Tibetans, so they changed their ethnicity to tamang, which is what they still write till date. The cultural and traditions of these people are similar to the Tibetan across the border. Gatlang is a traditional Tamang village. Gatlang set high on a hillside among terraced fields is the Tamang settlement. One can also visit a Tamang monastery and the beautiful Parvatikunda Lake at Gatlang. From the viewpoint at Bahundanda near these settlements, called Parwati Kunda and one can also see a panoramic view of Lantang, Kerung, and the Ganesh Himal, Sanjen Himal ranges. Bathing in the hot, healing waters of the natural spring at Tatopani is an exhilarating experience. Nagathali (3165m, view point) in Thuman VDC is surrounded by beautiful views of Langtang, Kerung, Ganesh Himal and Sanjen Himal ranges. Nagthali used to be a popular meditation center for the local monks and priests. The ancient monasteries and houses adorned with rich wood engravings at Thuman village are an unforgettable experience. Timure is on the old trade route to Tibet. A fort at Rasuwagadi in Timure is a historical reminder of the Nepal-Tibet relations that has existed for many centuries. A suspension bridge here links Nepal and Tibet.