Renewed Life for Gastown: an Economic Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VHS March 08.Indd

Vancouver Historical Society NEWSLETTER ISSN 0042 - 2487 Vol. 47 No. 6 March 2008 Inside the H. Y. Louie Family March Speaker: Willis Louie Both of these enterprises are community minded in raising funds for local projects and promoting health issues. But what isn’t known is the racial barrier in every day life of the H.Y. Louie family. They faced colour barriers to getting jobs and even to join- ing the military. They were also were the subject of a public outcry when they moved their residence to the Dunbar-Southlands neighbourhood of Vancouver. H.Y. Louie had 11 children and most have passed away but the youngest, Willis, will relate his family’s story. He will tell not only the success of the business side of the family but their overcoming the racial discrimina- tion during the Chinese Exclusion years. As high school and university students, he and his siblings broke the colour barriers on the soccer fields and on the basketball courts. His siblings also answered to the call of war. One of his brothers, Quan, served overseas as a bomber aimer with the RCAF and on a mission over Germany, made the ultimate sacrifice. ABOVE: Willis Louie The Province of British Columbia honoured Quan Louie’s memory by The story of the H.Y. Louie family is a fa- naming a lake after him. Quan Lake is located north of the Vancouver’s miliar one — a family business arising from watershed. humble beginnings in Chinatown as a small wholesale grocery outlet to the present day ubiquitous chain of London Drugs and the Market Place IGA. -

Hop-On Hop-Off

HOP-ON Save on Save on TOURS & Tour Attractions SIGHTSEEING HOP-OFF Bundles Packages Bundle #1 Explore the North Shore Hop-On in Vancouver + • Capilano Suspension Bridge Tour Whistler • Grouse Mountain General Admission* • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass This bundle takes Sea-to-Sky literally! Start by taking in the spectacular ocean You Save views in Vancouver before winding along Adult $137 $30 the Sea-to-Sky Highway and ascending into Child $61 $15 the coastal mountains. 1 DAY #1: 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Your perfect VanDAY #2: Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour* Sea to Bridge Experience You Save • Capilano Suspension Bridge day on Hop-On, Adult $169 $30 • Vancouver Aquarium Child $89 $15 • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass You Save Hop-Off Operates: Dec 1, 2019 - Apr 30, 2020 Classic Pass Adult $118 $30 The classic pass is valid for 48 hours and * Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour operates: Child $53 $15 Choose from 26 stops at world-class • Dec 1, 2019 - Jan 6, 2020, Daily includes both Park and City Routes • Apr 1 - 30, 2020, Daily attractions and landmarks at your • Jan 8 - Mar 29, 2020, Wed, Fri, Sat & Sun 2 own pace with our Hop-On, Hop-Off Hop-On, Hop-Off + WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 - APR 30, 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Sightseeing routes. $49 $25 Lookout Tower Special Adult Child (3-12) Bundle #2 Hop-On in Vancouver + • Vancouver Lookout Highlights Tour Victoria • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass • 26 stops, including 6 stops in Stanley Park CITY Route PARK Route and 1 stop at Granville Island Take an in-depth look at Vancouver at You Save (Blue line) (Green Line) your own pace before journeying to the Adult $53 $15 • Recorded commentary in English, French, Spanish, includes 9 stops includes 17 stops quaint island city of Victoria on a full day of Child $27 $8 German, Japanese, Korean & Mandarin Fully featuring: featuring: exploration. -

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver J EAN BARMAN1 anada has become increasingly urban. More and more people choose to live in cities and towns. Under a fifth did so in 1871, according to the first census to be held after Canada C 1867 1901 was formed in . The proportion surpassed a third by , was over half by 1951, and reached 80 percent by 2001.2 Urbanization has not benefited Canadians in equal measure. The most adversely affected have been indigenous peoples. Two reasons intersect: first, the reserves confining those deemed to be status Indians are scattered across the country, meaning lives are increasingly isolated from a fairly concentrated urban mainstream; and second, the handful of reserves in more densely populated areas early on became coveted by newcomers, who sought to wrest them away by licit or illicit means. The pressure became so great that in 1911 the federal government passed legislation making it possible to do so. This article focuses on the second of these two reasons. The city we know as Vancouver is a relatively late creation, originating in 1886 as the western terminus of the transcontinental rail line. Until then, Burrard Inlet, on whose south shore Vancouver sits, was home to a handful of newcomers alongside Squamish and Musqueam peoples who used the area’s resources for sustenance. A hundred and twenty years later, apart from the hidden-away Musqueam Reserve, that indigenous presence has disappeared. 1 This article originated as a paper presented to the Canadian Historical Association, May 2007. I am grateful to all those who commented on it and to Robert A.J. -

Vancouver British Columbia

ATTRACTIONS | DINING | SHOPPING | EVENTS | MAPS VISITORS’ CHOICE Vancouver British Columbia SUMMER 2017 visitorschoice.com COMPLIMENTARY Top of Vancouver Revolving Restaurant FINE DINING 560 FEET ABOVE SEA LEVEL! Continental Cuisine with fresh seafood Open Daily Lunch, Dinner & Sunday Brunch 555 West Hastings Street • Reservations 604-669-2220 www.topofvancouver.com No elevator charge for restaurant patrons Top of Vancouver VSp16 fp.indd 1 3/13/16 7:00:35 PM 24 LEARN,LEARN, EXPLOREEXPLORE && SAVESAVE UUPP TTOO $1000.00$1000.00 LEARN,History of Vancouver, EXPLORE Explore 60+ Attractions, & SAVE Valid 2 Adults UP & T2 ChildrenO $1000.00 ( 12 & under) TOURISM PRESS RELEASE – FALL 2 016 History of Vancouver, Explore 60+ Attractions, Valid 2 Adults & 2 Children (12 & under) History of Vancouver, Explore 60+ Attractions, Valid 2 Adults & 2 Children ( 12 & under) “CITY PASSPORT CAN SAVE YOUR MARRIAGE” If you are like me when you visit a city with the family, you always look to keep everyone happy by keeping the kids happy, the wife happy, basi- cally everybody happy! The Day starts early: “forget the hair dryer, Purchase Vancouver’s Attraction Passport™ and Save! we’ve got a tour bus to catch”. Or “Let’s go to PurchasePurchase Vancouver’s Vancouver’s AttractionAttraction Passport™Passport™ aandnd SSave!ave! the Aquarium, get there early”, “grab the Trolley BOPurNUS:ch Overase 30 Free VancTickets ( 2ou for 1 veoffersr’s ) at top Attr Attractions,acti Museums,on P Rassestaurants,port™ Vancouve ar Lookout,nd S Drave. Sun Yat! BONUS:BONUS Over: Ove 30r 30 Free Free Tickets Tickets ( (2 2 for fo r1 1 offers offers ) )at at top top Attractions, Attractions, Museums, RRestaurants,estaurants, VVancouverancouver Lookout, Lookout, Dr Dr. -

VANCOUVER's MISSING MIDDLE Abstract

VANCOUVER’S MISSING MIDDLE ComparingVANCOUVER’S Urban Forms to InformMISSING New Residential MIDDL BuildingE Typologies in Vancouver Comparing Urban Forms to Inform Residential Building TypologiesJames Beaudreau for Vancouver School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia November 2014 James Beaudreau School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia November 2014 VANCOUVER'S MISSING MIDDLE Abstract by Vancouver, British Columbia is JAMES ALFRED BEAUDREAU experiencing rapid growth. The city currently faces difficult questions about B.S., Northeastern University, 2002 how it will grow, and how to ensure this M.P.A., San Francisco State University, 2009 growth is sustainable. Some kind of intensification of residential land uses will A PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF undoubtedly need to be part of the strategy THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF for increasing the supply of housing in the city, but questions remain about how this MASTER OF ARTS (PLANNING) intensification should be carried out. This report compares the built form of in Vancouver's low-density, single-family THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES communities to older and more established neighbourhoods in cities in both North School of Community and Regional Planning America and Europe. The purpose of this exercise is to understand how the built form We accept this project as conforming of the city, such as the street patterns and to the required standard types of buildings, affect the level of density. This report finds that there is a ...................................................... significant amount of land in Vancouver that could be redeveloped to meet future ..................................................... housing needs. ..................................................... THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November 2014 © James Alfred Beaudreau, 2014 Vancouver’s Missing Middle i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS available to answer questions or help My partner, Greg, will forever be resolve problems. -

Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and Written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; Updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013

Early Trail Building in the New Colony of British Columbia — John Hall’s Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013. A recent “find” of colonial correspondence in the British Columbia Archives tells a story about the construction of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails between 1862 and 1864 by pioneer settler John Hall. (In 1870 Hall pre-empted 160 acres of Crown Land on Indian Arm and became Belcarra’s first European settler.) The correspondence involves a veritable “who’s who” of people in the administration in the young ‘Colony of British Columbia’. This historic account serves to highlight one of the many challenges faced by our pioneers during the period of colonial settlement in British Columbia. Sir James Douglas When the Fraser River Gold Rush began in the spring of 1858, there were only about 250 to 300 Europeans living in the Fraser Valley. The gold rush brought on the order of 30,000 miners flocking to the area in the quest for riches, many of whom came north from the California gold fields. As a result, the British Colonial office declared a new Crown colony on the mainland called ‘British Columbia’ and appointed Sir James Douglas as the first Governor. (1) The colony was first proclaimed at Fort Langley on 19th November, 1858, but in early 1859 the capital was moved to the planned settlement called ‘New Westminster’, Sir James Douglas strategically located on the northern banks of the Fraser River. -

12 Day Spectacular British Columbia & Alberta

Tour Code RRIP 12 Day Spectacular British Columbia & Alberta 12 days Created on: 2 Oct, 2021 Day 1: Arrive in Vancouver, BC Vancouver, located on Canada's Pacific coast is spectacular by nature! Surrounded by ocean and a backdrop of lush rainforest, snow-capped mountains and fjords, this "city of nature" is an ethnically diverse, modern and laid-back metropolis renowned for its mix of urban, outdoor and wildlife adventures. There is no easy way to describe Vancouver, rated as one of the world's topmost live-able cities; you'll just have to see for yourself. Overnight: Vancouver Included Meal(s): Dinner Day 2: Vancouver, BC Today we embark on a full day of sightseeing in Vancouver as we explore the culture, art and history that comes together to define the city. Our city tour includes the neighbourhoods of Gastown, Chinatown, English Bay, Robson Street and Stanley Park, a National Historic Site of Canada featuring 400 hectares of coastal rainforest in the heart of Vancouver.Capilano Suspension Park, most well known for the famed Capilano Suspension Bridge also features history and culture of the Salish First Nation. Take a walk across the famed Capilano Suspension Bridge, surrounded by towering forest hanging high above the Capilano River; the bridge was originally built in 1889.Next we take in Granville Island at the Granville Island Public Market featuring an incredible assortment of food and produce, unique gifts and handcrafted gifts that has all been locally sourced and produced.Enjoy the remainder of the evening at leisure to explore Vancouver how you choose. -

George Black — Early Pioneer Settler on the Coquitlam River

George Black — Early Pioneer Settler on the Coquitlam River Researched and written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, December 2018. The ‘Colony of British Columbia’ was proclaimed at Fort Langley on November 19th,1858. In early 1859, Colonel Richard Clement Moody, RE, selected the site for the capital of the colony on the north side of the Fraser River where the river branches. The Royal Engineers established their camp at ‘Sapperton’ and proceeded to layout the future townsite of ‘Queensborough’ (later ‘New Westminster’). On July 17th, 1860, ‘New Westminster’ incorporated to become the first municipality in Western Canada. During the winter of 1858–59, the Fraser River froze over for several months and Colonel Moody realized his position when neither supply boat nor gun-boat could come to his aid in case of an attack. As a consequence, Colonel Moody built a “road” to Burrard Inlet in the summer of 1859 as a military expediency, in order that ships might be accessible via salt water. The “road” was initially just a pack trail that was built due north from ‘Sapperton’ in a straight line to Burrard Inlet. In 1861, the pack trail was upgraded to a wagon road ― known today as ‘North Road’. (1) The ‘Pitt River Road’ from New Westminster to ‘Pitt River Meadows’ was completed in June 1862. (2) In the summer of 1859, (3)(4) the first European family to settle in the Coquitlam area arrived on the schooner ‘Rob Roy’ on the west side of the Pitt River to the area known as ‘Pitt River Meadows’ (today ‘Port Coquitlam’) — Alexander McLean (1809–1889), his wife (Jane), and their two small boys: Alexander (1851–1932) and Donald (1856–1930). -

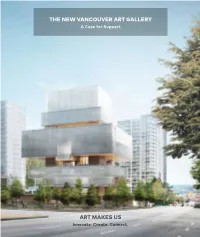

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

Early Vancouver Volume

Early Vancouver Volume Two By: Major J.S. Matthews, V.D. 2011 Edition (Originally Published 1933) Narrative of Pioneers of Vancouver, BC Collected During 1932. Supplemental to volume one collected in 1931. About the 2011 Edition The 2011 edition is a transcription of the original work collected and published by Major Matthews. Handwritten marginalia and corrections Matthews made to his text over the years have been incorporated and some typographical errors have been corrected, but no other editorial work has been undertaken. The edition and its online presentation was produced by the City of Vancouver Archives to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the City's founding. The project was made possible by funding from the Vancouver Historical Society. Copyright Statement © 2011 City of Vancouver. Any or all of Early Vancouver may be used without restriction as to the nature or purpose of the use, even if that use is for commercial purposes. You may copy, distribute, adapt and transmit the work. It is required that a link or attribution be made to the City of Vancouver. Reproductions High resolution versions of any graphic items in Early Vancouver are available. A fee may apply. Citing Information When referencing the 2011 edition of Early Vancouver, please cite the page number that appears at the bottom of the page in the PDF version only, not the page number indicated by your PDF reader. Here are samples of how to cite this source: Footnote or Endnote Reference: Major James Skitt Matthews, Early Vancouver, Vol. 2 (Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2011), 33. Bibliographic Entry: Matthews, Major James Skitt. -

2013 Heritage Register 2013 TABLE of CONTENTS

HERITAGE REGISTER 2013 heritage register 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 ‘THE AMBITIOUS CITY’ 5 CHRONOLOGY OF HISTORIC EVENTS 6 HERITAGE REGISTER BUILDINGS 10 HERITAGE REGISTER SITES & STRUCTURES 119 HERITAGE LANDSCAPE FEATURES 124 HERITAGE CHARACTER AND CONSERVATION AREAS 129 INDEX OF BUILDINGS 132 INDEX OF HERITAGE REGISTER SITES & STRUCTURES 134 INDEX OF LANDSCAPE FEATURES 134 INDEX OF CHARACTER AND CONSERVATION AREAS 134 1 heritage register 2013 INTRODUCTION • The North Shore Inventory, 1983 This initial survey was undertaken by the North Shore he City of North Vancouver has a proud legacy of Heritage Advisory Committee, and identifi ed key historic settlement, and was offi cially incorporated as a new sites across the three North Shore municipalities. Tmunicipality in 1907 after it broke away from the District of North Vancouver. As a result of its ongoing growth • The Ambitious City: The City of North Vancouver and development, the City retains many signifi cant examples of Heritage Inventory, 1988-89 historic places that tell the stories of the past and continue to be Involved a comprehensive street-by-street survey of the valued by the community. The City of North Vancouver Heritage entire City, and identifi cation and evaluation of a number Register 2010 is a catalogue of existing heritage resources located of signifi cant sites, undertaken by Foundation Group within City boundaries. This project has provided a comprehensive Designs. update of previous inventory information that identifi es a broad range of historic resources such as buildings, structures, sites and • The Versatile-Pacifi c Shipyards Heritage Report, 1991 notable landscape features. The Heritage Register represents an A comprehensive survey of the industrial buildings ongoing civic commitment to monitor and conserve the City’s of the old Burrard Drydock site, undertaken by F.G. -

A HISTORY of the CITY AND•DISTRICT of NORTH VANCOUVER by Kathleen Marjprie Woo&Ward-Reynol&S Thesis Submitted in Parti

A HISTORY OF THE CITY AND•DISTRICT OF NORTH VANCOUVER by Kathleen Marjprie Woo&ward-Reynol&s Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment The Requirements for the Degree of H ALS TER OF ARTS in the Department of HISTORY The University,of British Columbia October 1943 ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page iv Acknowledgement s 1 I Introduction 10 II Moodyville 38 III Pre-emptions 48 IV Municipal Development QQ V Lynn Valley 91 VI Ferries 90 VII Railways and Roads 116 VIII Business and Industry 139 IX Schools and Churches 159 X Conclusion 163 Bibliography PLATE Moodyville Dakin's Fire Insurance Map - 25 Ill Appendix A, Statistical Tables Table A Sale of Municipal Lands for Taxes, 1893 - 1895 1 B Land Assessments, 1892 - 1905 i C Tax Collections, 1927 - 1932 ii D Summary of Tax Collections City of North Vancouver, 1932 iii E Reeves, Mayors and Commissioners of North Vancouver, 1891 - 1936 iv F Statistical Information Relative to the City of North Vancouver G Statistical Information Relative to the District of North Vancouver vi H City of North Vancouver Assessments, 1927 - 1942 vii I District of North Vancouver Assessments, 1927 - 1942 viii Appendix B, Maps Lynn Valley ix Fold Map of North Vancouver x lit Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to the writing of this thesis, and to them all I am deeply grateful. For invaluable assistance at the Archives of British Columbia, I am greatly indebted to Miss Madge Wolfenden. My greatful thanks are also due to Commissioner G.W. Vance of North Vancouver for access to Municipal records, and to the North Shore Press for the use of their files.