VANCOUVER's MISSING MIDDLE Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VHS March 08.Indd

Vancouver Historical Society NEWSLETTER ISSN 0042 - 2487 Vol. 47 No. 6 March 2008 Inside the H. Y. Louie Family March Speaker: Willis Louie Both of these enterprises are community minded in raising funds for local projects and promoting health issues. But what isn’t known is the racial barrier in every day life of the H.Y. Louie family. They faced colour barriers to getting jobs and even to join- ing the military. They were also were the subject of a public outcry when they moved their residence to the Dunbar-Southlands neighbourhood of Vancouver. H.Y. Louie had 11 children and most have passed away but the youngest, Willis, will relate his family’s story. He will tell not only the success of the business side of the family but their overcoming the racial discrimina- tion during the Chinese Exclusion years. As high school and university students, he and his siblings broke the colour barriers on the soccer fields and on the basketball courts. His siblings also answered to the call of war. One of his brothers, Quan, served overseas as a bomber aimer with the RCAF and on a mission over Germany, made the ultimate sacrifice. ABOVE: Willis Louie The Province of British Columbia honoured Quan Louie’s memory by The story of the H.Y. Louie family is a fa- naming a lake after him. Quan Lake is located north of the Vancouver’s miliar one — a family business arising from watershed. humble beginnings in Chinatown as a small wholesale grocery outlet to the present day ubiquitous chain of London Drugs and the Market Place IGA. -

Hop-On Hop-Off

HOP-ON Save on Save on TOURS & Tour Attractions SIGHTSEEING HOP-OFF Bundles Packages Bundle #1 Explore the North Shore Hop-On in Vancouver + • Capilano Suspension Bridge Tour Whistler • Grouse Mountain General Admission* • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass This bundle takes Sea-to-Sky literally! Start by taking in the spectacular ocean You Save views in Vancouver before winding along Adult $137 $30 the Sea-to-Sky Highway and ascending into Child $61 $15 the coastal mountains. 1 DAY #1: 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Your perfect VanDAY #2: Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour* Sea to Bridge Experience You Save • Capilano Suspension Bridge day on Hop-On, Adult $169 $30 • Vancouver Aquarium Child $89 $15 • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass You Save Hop-Off Operates: Dec 1, 2019 - Apr 30, 2020 Classic Pass Adult $118 $30 The classic pass is valid for 48 hours and * Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour operates: Child $53 $15 Choose from 26 stops at world-class • Dec 1, 2019 - Jan 6, 2020, Daily includes both Park and City Routes • Apr 1 - 30, 2020, Daily attractions and landmarks at your • Jan 8 - Mar 29, 2020, Wed, Fri, Sat & Sun 2 own pace with our Hop-On, Hop-Off Hop-On, Hop-Off + WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 - APR 30, 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Sightseeing routes. $49 $25 Lookout Tower Special Adult Child (3-12) Bundle #2 Hop-On in Vancouver + • Vancouver Lookout Highlights Tour Victoria • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass • 26 stops, including 6 stops in Stanley Park CITY Route PARK Route and 1 stop at Granville Island Take an in-depth look at Vancouver at You Save (Blue line) (Green Line) your own pace before journeying to the Adult $53 $15 • Recorded commentary in English, French, Spanish, includes 9 stops includes 17 stops quaint island city of Victoria on a full day of Child $27 $8 German, Japanese, Korean & Mandarin Fully featuring: featuring: exploration. -

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver J EAN BARMAN1 anada has become increasingly urban. More and more people choose to live in cities and towns. Under a fifth did so in 1871, according to the first census to be held after Canada C 1867 1901 was formed in . The proportion surpassed a third by , was over half by 1951, and reached 80 percent by 2001.2 Urbanization has not benefited Canadians in equal measure. The most adversely affected have been indigenous peoples. Two reasons intersect: first, the reserves confining those deemed to be status Indians are scattered across the country, meaning lives are increasingly isolated from a fairly concentrated urban mainstream; and second, the handful of reserves in more densely populated areas early on became coveted by newcomers, who sought to wrest them away by licit or illicit means. The pressure became so great that in 1911 the federal government passed legislation making it possible to do so. This article focuses on the second of these two reasons. The city we know as Vancouver is a relatively late creation, originating in 1886 as the western terminus of the transcontinental rail line. Until then, Burrard Inlet, on whose south shore Vancouver sits, was home to a handful of newcomers alongside Squamish and Musqueam peoples who used the area’s resources for sustenance. A hundred and twenty years later, apart from the hidden-away Musqueam Reserve, that indigenous presence has disappeared. 1 This article originated as a paper presented to the Canadian Historical Association, May 2007. I am grateful to all those who commented on it and to Robert A.J. -

Vancouver British Columbia

ATTRACTIONS | DINING | SHOPPING | EVENTS | MAPS VISITORS’ CHOICE Vancouver British Columbia SUMMER 2017 visitorschoice.com COMPLIMENTARY Top of Vancouver Revolving Restaurant FINE DINING 560 FEET ABOVE SEA LEVEL! Continental Cuisine with fresh seafood Open Daily Lunch, Dinner & Sunday Brunch 555 West Hastings Street • Reservations 604-669-2220 www.topofvancouver.com No elevator charge for restaurant patrons Top of Vancouver VSp16 fp.indd 1 3/13/16 7:00:35 PM 24 LEARN,LEARN, EXPLOREEXPLORE && SAVESAVE UUPP TTOO $1000.00$1000.00 LEARN,History of Vancouver, EXPLORE Explore 60+ Attractions, & SAVE Valid 2 Adults UP & T2 ChildrenO $1000.00 ( 12 & under) TOURISM PRESS RELEASE – FALL 2 016 History of Vancouver, Explore 60+ Attractions, Valid 2 Adults & 2 Children (12 & under) History of Vancouver, Explore 60+ Attractions, Valid 2 Adults & 2 Children ( 12 & under) “CITY PASSPORT CAN SAVE YOUR MARRIAGE” If you are like me when you visit a city with the family, you always look to keep everyone happy by keeping the kids happy, the wife happy, basi- cally everybody happy! The Day starts early: “forget the hair dryer, Purchase Vancouver’s Attraction Passport™ and Save! we’ve got a tour bus to catch”. Or “Let’s go to PurchasePurchase Vancouver’s Vancouver’s AttractionAttraction Passport™Passport™ aandnd SSave!ave! the Aquarium, get there early”, “grab the Trolley BOPurNUS:ch Overase 30 Free VancTickets ( 2ou for 1 veoffersr’s ) at top Attr Attractions,acti Museums,on P Rassestaurants,port™ Vancouve ar Lookout,nd S Drave. Sun Yat! BONUS:BONUS Over: Ove 30r 30 Free Free Tickets Tickets ( (2 2 for fo r1 1 offers offers ) )at at top top Attractions, Attractions, Museums, RRestaurants,estaurants, VVancouverancouver Lookout, Lookout, Dr Dr. -

12 Day Spectacular British Columbia & Alberta

Tour Code RRIP 12 Day Spectacular British Columbia & Alberta 12 days Created on: 2 Oct, 2021 Day 1: Arrive in Vancouver, BC Vancouver, located on Canada's Pacific coast is spectacular by nature! Surrounded by ocean and a backdrop of lush rainforest, snow-capped mountains and fjords, this "city of nature" is an ethnically diverse, modern and laid-back metropolis renowned for its mix of urban, outdoor and wildlife adventures. There is no easy way to describe Vancouver, rated as one of the world's topmost live-able cities; you'll just have to see for yourself. Overnight: Vancouver Included Meal(s): Dinner Day 2: Vancouver, BC Today we embark on a full day of sightseeing in Vancouver as we explore the culture, art and history that comes together to define the city. Our city tour includes the neighbourhoods of Gastown, Chinatown, English Bay, Robson Street and Stanley Park, a National Historic Site of Canada featuring 400 hectares of coastal rainforest in the heart of Vancouver.Capilano Suspension Park, most well known for the famed Capilano Suspension Bridge also features history and culture of the Salish First Nation. Take a walk across the famed Capilano Suspension Bridge, surrounded by towering forest hanging high above the Capilano River; the bridge was originally built in 1889.Next we take in Granville Island at the Granville Island Public Market featuring an incredible assortment of food and produce, unique gifts and handcrafted gifts that has all been locally sourced and produced.Enjoy the remainder of the evening at leisure to explore Vancouver how you choose. -

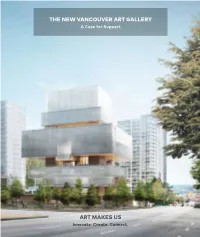

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

Vancouver Canada Public Transportation

Harbour N Lions Bay V B Eagle I P L E 2 A L A 5 A R C Scale 0 0 K G H P Legend Academy of E HandyDART Bus, SeaBus, SkyTrain Lost Property Customer Service Coast Express West Customer Information 604-488-8906 604-953-3333 o Vancouver TO HORSESHOE BAY E n Local Bus Routes Downtown Vancouver 123 123 123 i CHESTNUT g English Bay n l Stanley Park Music i AND LIONS BAY s t H & Vancouver Museum & Vancouver h L Anthropology Beach IONS B A A W BURRARD L Y AV BURRARD Park Museum of E B t A W Y 500 H 9.16.17. W 9 k 9 P Y a Lighthouse H.R.MacMillan G i 1 AVE E Vanier n Space Centre y r 3 AVE F N 1 44 Park O e s a B D o C E Park Link Transportation Major Road Network Limited Service Expo Line SkyTrain Exchange Transit Central Valley Greenway Central Valley Travel InfoCentre Travel Regular Route c Hospital Point of Interest Bike Locker Park & Ride Lot Peak Hour Route B-Line Route & Stop Bus/HOV Lane Bus Route Coast Express (WCE) West Millennium Line SkyTrain Shared Station SeaBus Route 4.7.84 A O E n Park 4 AVE 4 AVE l k C R N s H Observatory A E V E N O T 2 e S B University R L Caulfeild Columbia ta Of British Southam E 5 L e C C n CAULFEILD Gordon Memorial D 25 Park Morton L Gardens 9 T l a PINE 253.C12 . -

Vanartgallery.Bc.Ca WELCOME WE're SO GLAD YOU're HERE!

WHAT’S ON SPRING 2021 PLLAANN YYOOUURR VVIISSIITT vanartgallery.bc.ca WELCOME WE'RE SO GLAD YOU'RE HERE! VANCOUVER ART GALLERY 750 Hornby Street Vancouver BC V6Z 2H7 vanartgallery.bc.ca GALLERY HOURS MON: 10 AM–5 PM TUE: 12 PM–8 PM (by donation from 5-8 PM) WED: 10 AM–5 PM THU: 10 AM–5 PM FRI: 12 PM–8 PM SAT: 10 AM–5 PM SUN: 10 AM–5 PM BOOK TICKETS Purchase your timed-entry tickets online at N etickets.vanartgallery.bc.ca N Access multi-media guides and learning tools for select exhibitions by scanning QR Codes in the Gallery or by visiting exhibition webpages at vanartgallery.bc.ca R Publication available in the Gallery Store R MEMBERSHIP Become a Gallery Member to get unlimited admission to every exhibition and more! Join today in person at the Membership Desk, by phone at 604.662.4711 or online at vanartgallery.bc.ca/membership. T KEEP IN TOUCH T [email protected] @vanartgallery /vancouverartgallery @vanartgallery ACCESSIBILITY The Vancouver Art Gallery is wheelchair accessible. Street-level access is available through the Hornby and Robson Street entrances. Wheelchairs are available to visitors on a first-come, first-served basis, or can be reserved in advance by calling 604.662.4700. A Service Animal may accompany visitors to all public areas of the Gallery. BEFORE YOU BEGIN E YOUR EXPERIENCE We care about you and your safety. Since re-opening, procedures have been put in place to ensure that the Vancouver Art Gallery is safe, sanitized and ready to welcome all visitors, volunteers and staff. -

Stan Douglas Born 1960 in Vancouver

David Zwirner This document was updated December 12, 2019. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Stan Douglas Born 1960 in Vancouver. Lives and works in Vancouver. EDUCATION 1982 Emily Carr College of Art, Vancouver SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Stan Douglas: Doppelgänger, David Zwirner, New York, concurrently on view at Victoria Miro, London 2019 Stan Douglas: SPLICING BLOCK, Julia Stoschek Collection (JSC), Berlin [collection display] 2018 Stan Douglas: DCTs and Scenes from the Blackout, David Zwirner, New York 2017 Stan Douglas, Victoria Miro, London Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Les Champs Libres, Rennes, France 2016 Stan Douglas: Photographs, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg [catalogue] Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, Victoria Miro, London Stan Douglas, Hasselblad Center, Gothenburg, Sweden [organized on occasion of the artist receiving the 2016 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography] [catalogue] 2015 Stan Douglas: Interregnum, Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon [catalogue] Stan Douglas: Interregnum, Wiels Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels [catalogue] 2014 Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: Scotiabank Photography Award, Ryerson Image Centre, Ryerson University, Toronto [catalogue published in 2013] Stan Douglas, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh [catalogue] -

Loveyourcity-Contestrules

CONTEST RULES & REGULATIONS VANCOUVERBIAPARTNERSHIP.COM @LOVEYOURCITYCONTEST thethe prizeprize Enter to win the grand prize of an ultimate Vancouver staycation, dining, self care, movies, date night, swag, party basket, jewelry and more from your favourite Vancouver neighbourhoods. Valued at over $5000! Plus, follow each of the neighbourhoods on Instagram (listed on the next page) for weekly prizes! HowHow toto playplay Find love in your favourite Vancouver neighborhoods for a chance to win daily prizes PLUS a grand prize valued at over $5000! Visit any (or all!) of the participating Vancouver neighborhoods throughout the month of February. See the next page for a full list of the sixteen participating neighborhoods. Look out for the love installations and take a photo of or with it. They could be giant sweetheart candies, wooden hearts, murals, banners, umbrellas installations and more! See the next page for hints. Post the photo to your Instagram feed and tag @loveyourcitycontest and the hashtag of the neighbourhood you are visiting (#findloveyaletown, #findlovewest4th, etc.) You’ll be automatically entered to win daily prizes plus the grand prize valued at over $5000! The contest goes until Feb. 28, 2021. Good luck! importantimportant thingsthings toto note!note! The contest runs February 1-28, 2021. Any photos posted outside of those dates will not count towards the contest. Photos must be posted to the participants Instagram FEED. Instagram stories will not count. Each photo is an entry, there are no limits to entries. Due to the nature of some prizes (alcohol, etc.) participants must be 19+ to collect the prizes but families/children are encouraged to participate in the photo taking fun. -

23E Pender Street for Sale

E PENDER STREET 23ICONIC CHINATOWN HERITAGE BUILDING MERCIAL FOROM SALERE MM C A CO L L E E E L R B S E R T C A B O T I C E R A O L C Downtow WBODPVWFS-!CD Chinatow V ANCOUVER ROBERT THAM MARC SAUL* WILLOW KING 604.609.0882 Ext. 223 604.609.0882 Ext. 222 604.609.0882 Ext. 221 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] *Personal Real Estate Corporation. [email protected] | WWW.CORBELCOMMERCIAL.COM | 632 CITADEL PARADE, VANCOUVER BC, V6B 1X3 E. & O. E.: All information contained herein is from sources we deem reliable, and we have no reason to doubt its accuracy; however, no guarantee or responsibility is assumed thereof, and it shall not form any part of future contracts. Properties are submitted subject to errors and omissions and all information should be carefully verifi ed. All measurements quoted herein are approximate. 23 E PENDER STREET THE LOCATION Chinatown is one of Vancouver’s most exciting neighbourhoods, rich in history and filled with new and trendy places to live, work, and shop. The Chinatown district is home to a wide variety of boutique retailers, award-winning restaurants, and popular coffee shops. Located on East Pender Street between Main Street and Carrall Street, this emerging neighbourhood is home to many notable businesses including Kissa Tanto, Umaluma, Propaganda Coffee, Bao Bei, Aubade Coffee and many others. The area at large is growing rapidly, with several mixed-use development projects which have completed in recent years. With the proposed future St. -

VANCOUVER Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

VANCOUVER Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Vancouver | 2019 0 Vancouver is a top shopping destination in Canada, offering a diverse mix of high-end luxury boutiques and charming one-of-a kind shops that appeal to tourists and locals alike. Robson Street and neighbouring Alberni Street make up the downtown hub for internationally recognized brands and luxury retailers. Shoppers looking for local designers and boutiques can find them in South Granville, Gastown, Yaletown, Main Street, and Kitsilano. Each neighborhood offers its own distinctive character, from the trendy converted warehouses in Yaletown and cobblestone streets of Gastown to the established Robson Street and up-and-coming Main Street and Olympic Village areas. Not surprisingly, this famous tourist destination is a major draw to international retailers. Top brands that have recently entered the Vancouver market include IWC Schaffhausen Versace, Prada, Kate Spade, and Moncler. Vancouver has also given rise to famous brands such as Lululemon, Roots, Aritzia, Mountain Equipment Corp, and Saje, which have all grown from humble beginnings to become hugely successful on the international stage. VANCOUVER Famous for its natural beauty, urban sophistication, cultural diversity, and stable economy, Vancouver attracts newcomers and visitors from all over the world. A record- OVERVIEW breaking 10.3 million people visited the city and region in 2017, infusing $4.8 billion into the local economy. Cushman & Wakefield | Vancouver | 2019 1 VANCOUVER KEY RETAIL STREETS & AREAS ROBSON STREET YALETOWN Robson Street is Vancouver’s most famous shopping Primarily known as a warehouse district, Yaletown is now district, offering a wide range of international and local fully established as one of Vancouver’s most trendy nodes brands for both tourist and locals.