Ain Ghazal “Monumental” Figures: a Stylistic Analysis1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studeis in the History and Archaeology of Jordan Xii المملكة األردنية الهاشمية رقم اإليداع لدى دائرة المكتبة الوطنية )2004/5/1119(

STUDEIS IN THE HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF JORDAN XII المملكة اﻷردنية الهاشمية رقم اﻹيداع لدى دائرة المكتبة الوطنية )2004/5/1119( 565.039 Jordan Department of Antiquities Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan Amman: The Department, 2004. Vol. VIII. Deposit No.: 1119/5/2004. Descriptors:\Jordanian History \ Antiquities \\ Studies \\ Archaeology \ \ Conferences \ * تم إعداد بيانات الفهرسة والتصنيف اﻷولية من قبل دائرة المكتبات الوطنية STUDEIS IN THE HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF JORDAN XII Department of Antiquities Amman- Jordan HIS MAJESTY KING ABDULLAH THE SECOND IBN AL-HUSSEIN OF THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS PRINCE AL-HUSSEIN BIN ABDULLAH THE SECOND HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS PRINCE EL-HASSAN BIN TALAL THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN STUDEIS IN THE HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF JORDAN XII Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan Published by the Department of Antiquities, P.O.Box 88, ʻAmman 11118 Jordan Editorial Board Chief Dr. Monther Jamhawi Deputy Chief Editor Jihad Haron Editing Manager Dr. Ismail Melhem Editorial Board Hanadi Al-Taher Samia Khouri Arwa Masa'deh Najeh Hamdan Osama Eid English Text Revised by Dr. Alexander Wasse STUDIES IN THE HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF JORDAN XII: TRANSPARENT BORDERS Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 17 Maura Sala 117 SYSTEM OF TRANSLITERATION 19 THE CERAMIC ENSEMBLE FROM TABLE OF CONFERENCES 20 THE EB IIIB PALACE B AT KHIRBAT SPEECHES 21 AL-BATRAWI (NORTH-CENTRAL JORDAN): A PRELIMINARY REPORT HRH, Prince El-Hassan Bin Talal 21 IN THE CONTEXT OF EBA PALES- Presenting 29 TINE AND TRANSJORDAN A. J. Nabulsi and P. Schönrock-Nabulsi 31 Lorenzo Nigro 135 KHIRBAT AS-SAMRA CEMETERY: A KHIRBAT AL-BATRAWI 2010-2013: QUESTION OF DATING THE CITY DEFENSES AND THE PAL- ACE OF COPPER AXES Dr Ignacio Arce, Dr Denis Feissel, Dr 35 Detlev Kreikenbom and Dr Thomas Ma- Susanne Kerner 155 ria Weber THE EXCAVATIONS AT ABU SUNAY- THE ANASTASIUS EDICT PROJECT SILAH WITH PARTICULAR CONSID- ERATION OF FOOD RELATED OR- Dr. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

Ibn AI-Qaddah Series D--Gujrati

,, .... ... •. ~·· . '·( ·-'';..:_,_,. , .......,.,'---"--_,_,.,,:-c,"',-f., :-;. ~. ---"'::---- . ·. , 1 · .. ·" ·· Series· t...:.;_royal ~vo ' ·dzi. , 1 · ~ • ·, The lsmaili Society Series A No. 9 --- - - - - I l. Rahattt'l-Aql, by Hamidu'd-din al-Kirmani. Arab.. text, ed. by Dr, M. Krunil Hussein and Dr. M. Hilmy, Cairo, 1952. pp. 10--46-438-10. ~with index). Rs. 18/40 sh. f,:· . ' ·'1 ' ."; t •,,,... ·:,, ~~. · -,·~ ' . " ... ~ .• t' ..... Ibn AI-Qaddah Series D--Gujrati. (The Alleged Founder of lsmailism) ~GYi(ldl. ~~~Lt ~{\:)J · ~d,'tlH ~. cfi. ~-1, ~~l SECOND REVISED EDITION of The Ismaili Society Series A No. 1 \ ~~h~ {\--t '{\{ m~~{\1 ~Ll~~~ ~~~~~ 't-o-o ~(> ' I ~~ H:¥\9 ~·!JttJ. <3C) DY t ~l'il~d ~lHlt o-'t~-o [\ 9-..--:s:.% ~;j, 't~'t~ ~{tJttJ. W. lvANCW \'15 ~'( (formerly Assistant Keeper, the Asiatic Museum of th·e Russian I 'l:lltllt ~~ lt~{\ '1.-~-o Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg). ~::. '\~¥! ~·ut'l:l. '\- ~l.al1li:J1lltl ( ~~~ 1tf~H '!,!~~ ~ct) '1.-o-o ~;j, '\~'t~ ~·ut~. ,I. ~,. A-e· \ (.· ' ' 1957 Published by the Ismaili Society, BOMBAY. First publ~shed in 1946 NOTICE. ·' The aim of the "Ismaili Society••, founded in Bom bay on the 16th February 1946, is the promotion of independent and critical study of all matters connected with Ism;tilisrn, that is to say, of all branches of the Ismaili movement in Islam, their literature, history, philosophy, and so forth. The Society entirely excludes from its prpgramme any religious or political propa. 1 ganda or controversy, and does not intend to vindicate the viewpoint of any particular school in Ismailism. The ~'Ismaili Society" propose to publish monographs on subjects connected with such studies, critical edi tions of the original texts of early Isrnaili works, their translations, and also collections of shorter papers and notes. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Al Nakba Background

Atlas of Palestine 1917 - 1966 SALMAN H. ABU-SITTA PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY LONDON Chapter 3: The Nakba Chapter 3 The Nakba 3.1 The Conquest down Palestinian resistance to British policy. The The immediate aim of Plan C was to disrupt Arab end of 1947 marked the greatest disparity between defensive operations, and occupy Arab lands The UN recommendation to divide Palestine the strength of the Jewish immigrant community situated between isolated Jewish colonies. This into two states heralded a new period of conflict and the native inhabitants of Palestine. The former was accompanied by a psychological campaign and suffering in Palestine which continues with had 185,000 able-bodied Jewish males aged to demoralize the Arab population. In December no end in sight. The Zionist movement and its 16-50, mostly military-trained, and many were 1947, the Haganah attacked the Arab quarters in supporters reacted to the announcement of veterans of WWII.244 Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, killing 35 Arabs.252 On the 1947 Partition Plan with joy and dancing. It December 18, 1947, the Palmah, a shock regiment marked another step towards the creation of a The majority of young Jewish immigrants, men established in 1941 with British help, committed Jewish state in Palestine. Palestinians declared and women, below the age of 29 (64 percent of the first reported massacre of the war in the vil- a three-day general strike on December 2, 1947 population) were conscripts.245 Three quarters of lage of al-Khisas in the upper Galilee.253 In the first in opposition to the plan, which they viewed as the front line troops, estimated at 32,000, were three months of 1948, Jewish terrorists carried illegal and a further attempt to advance western military volunteers who had recently landed in out numerous operations, blowing up buses and interests in the region regardless of the cost to Palestine.246 This fighting force was 20 percent of Palestinian homes. -

RECLAIMING HOME the Struggle for Socially Just Housing, Land and Property Rights in Syria,Iraq and Libya

RECLAIMING HOME The struggle for socially just housing, land and property rights in Syria,Iraq and Libya Edited by Hannes Baumann RECLAIMING HOME The struggle for socially just housing, land and property rights in Syria, Iraq and Libya Edited by Hannes Baumann RECLAIMING HOME The struggle for socially just housing, land and property rights in Syria, Iraq and Libya Edited by Hannes Baumann Contributors Leïla Vignal Nour Harastani and Edwar Hanna Suliman Ibrahim Javier Gonzalez Ina Rehema Jahn and Amr Shannan Sangar Youssif Salih and Kayfi Maghdid Qadr Thomas McGee Not for Sale © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be printed, reproduced or utilized in any from by any means without prior written permission from the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the original authors. They do not necessarily represent those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Cartographic Design: Thiago Soveral Cover Illustration: Moshtari Hillal Graphic Design: Mehdi Jelliti Published in 2019 by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s Regional Project «For Socially Just Development in MENA» TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Thomas Claes ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 05 Introduction Hannes Baumann ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

F-Dyd Programme

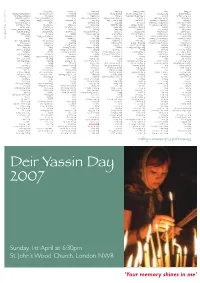

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab -

Palestine's Ongoing Nakba

al majdal DoubleDouble IssueIssue No.No. 39/4039/40 BADIL Resource Center Resource BADIL quarterly magazine of (Autumn(Autumn 20082008 / WinterWinter 2009)2009) BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights jjabaliyaabaliya a wwomanoman wearswears a bellbell carriescarries a light callscalls searchessearches by Suheir Hammad through madness of deir yessin calls for rafah for bread orange peel under nails blue glass under feet gathers children in zeitoun sitting with dead mothers she unearths tunnels and buries sun onto trauma a score and a day rings a bell she is dizzy more than yesterday less than tomorrow a zig zag back dawaiyma back humming suba back shatilla back ramleh back jenin back il khalil back il quds Palestine's all of it all underground in ancestral chests she rings a bell promising something she can’t see faith is that faith is this all over the land under the belly of wind she perfumed the love of a burning sea Ongoing concentrating refugee camp crescent targeted red NNakbaakba a girl’s charred cold face dog eaten body angels rounded into lock down shelled injured shock weapons for advancing armies clearing forests sprayed onto a city o sage tree human skin contact explosion these are our children Double Issue No. 39/40 (Autumn 2008 / Winter 2009) Winter / 2008 (Autumn 39/40 No. Issue Double she chimes through nablus back yaffa backs shot under spotlight phosphorous murdered libeled public relations public quarterly magazine quarterly relation a bell fired in jericho rings through blasted windows a woman Autumn 2008 / Winter 2009 1 carries bones in bags under eyes disbelieving becoming al-Majdal numb dumbed by numbers front and back gaza onto gaza JJaffaaffa 1948....Gaza1948....Gaza 20082008 for gaza am sorry gaza am sorry she sings for the whole powerless world her notes pitch perfect the bell a death toll BADIL takes a rights-based approach to the Palestinian refugee issue through research, advocacy, and support of community al-Majdal is a quarterly magazine of participation in the search for durable solutions. -

Financing Racism and Apartheid

Financing Racism and Apartheid Jewish National Fund’s Violation of International and Domestic Law PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY August 2005 Synopsis The Jewish National Fund (JNF) is a multi-national corporation with offices in about dozen countries world-wide. It receives millions of dollars from wealthy and ordinary Jews around the world and other donors, most of which are tax-exempt contributions. JNF aim is to acquire and develop lands exclusively for the benefit of Jews residing in Israel. The fact is that JNF, in its operations in Israel, had expropriated illegally most of the land of 372 Palestinian villages which had been ethnically cleansed by Zionist forces in 1948. The owners of this land are over half the UN- registered Palestinian refugees. JNF had actively participated in the physical destruction of many villages, in evacuating these villages of their inhabitants and in military operations to conquer these villages. Today JNF controls over 2500 sq.km of Palestinian land which it leases to Jews only. It also planted 100 parks on Palestinian land. In addition, JNF has a long record of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel as reported by the UN. JNF also extends its operations by proxy or directly to the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the West Bank and Gaza. All this is in clear violation of international law and particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention which forbids confiscation of property and settling the Occupiers’ citizens in occupied territories. Ethnic cleansing, expropriation of property and destruction of houses are war crimes. As well, use of tax-exempt donations in these activities violates the domestic law in many countries, where JNF is domiciled. -

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Ilan Pappe

PRAISE FOR THE ETHNIC CLEANSING OF PALESTINE ‘Ilan Pappe is Israel’s bravest, most principled, most incisive historian.’ —John Pilger ‘Ilan Pappe has written an extraordinary book of profound relevance to the past, present, and future of Israel/Palestine relations.’ —Richard Falk, Professor of International Law and Practise, Princeton University ‘If there is to be real peace in Palestine/Israel, the moral vigour and intellectual clarity of The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine will have been a major contributor to it.’ —Ahdaf Soueif, author of The Map of Love ‘This is an extraordinary book – a dazzling feat of scholarly synthesis and Biblical moral clarity and humaneness.’ —Walid Khalidi, Former Senior Research Fellow, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University ‘Fresh insights into a world historic tragedy, related by a historian of genius.’ —George Galloway MP ‘Groundbreaking research into a well-kept Israeli secret. A classic of historical scholarship on a taboo subject by one of Israel’s foremost New Historians.’ —Ghada Karmi, author of In Search of Fatima ‘Ilan Pappe is out to fight against Zionism, whose power of deletion has driven a whole nation not only out of its homeland but out of historic memory as well. A detailed, documented record of the true history of that crime, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine puts an end to the Palestinian “Nakbah” and the Israeli “War of Independence” by so compellingly shifting both paradigms.’ —Anton Shammas, Professor of Modern Middle Eastern Literature, University of Michigan ‘An instant classic. Finally we have the authoritative account of an historic event, which continues to shape our world today, and drives the conflict in the Middle East. -

Catastrophe Remembered Palest

01_Masahla prelims 28/7/05 2:28 pm Page i About this book The war of 1948 is known to Israelis as the “War of Independence”. But for Palestinians, the war is forever the Nakba, “The Catastrophe”. The conflict led to the creation of the state of Israel and resulted in the destruction of much of Palestinian society by Zionist forces. Approxi- mately 90 per cent of the Palestinians who lived in the major part of Palestine upon which Israel was established became refugees. The minority of Palestinians – 160,000 – who remained behind, are one of the main subjects of this book. Many of them were forced out of their homes and became second-class citizens of the state of Israel. As such, they were subject to a system of military administration between 1948 and 1966 by a government that confiscated the bulk of their lands. For the Palestinians, both refugees and non-refugees, the traumatic events of 1948 have become central to Palestinian history, memory and identity. Moreover, in recent years Palestinians have been producing memories of the Nakba, compiling and recording oral history and holding annual commemorations designed to preserve the memory of the catastrophe, while emphasising the link between refugee rights, identity and memory. In the absence of a rich source of Palestinian docu- mentary records, oral history and interviews with internally displaced Palestinians are a critical and natural source for constructing a more com- prehensible narrative of their experiences. This collection is dedicated to the memory of Edward W. Said (1935– 2003), whose voice articulated the aspirations of the disenfranchised, the oppressed and the marginalised, and whose message was humanist and universal, extending beyond Palestine to touch wide audiences.