The Tabernacle 1816-1829

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage-Statement

Document Information Cover Sheet ASITE DOCUMENT REFERENCE: WSP-EV-SW-RP-0088 DOCUMENT TITLE: Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’: Final version submitted for planning REVISION: F01 PUBLISHED BY: Jessamy Funnell – WSP on behalf of PMT PUBLISHED DATE: 03/10/2011 OUTLINE DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS ON CONTENT: Uploaded by WSP on behalf of PMT. Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’ ES Chapter: Final version, submitted to BHCC on 23rd September as part of the planning application. This document supersedes: PMT-EV-SW-RP-0001 Chapter 6 ES - Cultural Heritage WSP-EV-SW-RP-0073 ES Chapter 6: Cultural Heritage - Appendices Chapter 6 BSUH September 2011 6 Cultural Heritage 6.A INTRODUCTION 6.1 This chapter assesses the impact of the Proposed Development on heritage assets within the Site itself together with five Conservation Areas (CA) nearby to the Site. 6.2 The assessment presented in this chapter is based on the Proposed Development as described in Chapter 3 of this ES, and shown in Figures 3.10 to 3.17. 6.3 This chapter (and its associated figures and appendices) is not intended to be read as a standalone assessment and reference should be made to the Front End of this ES (Chapters 1 – 4), as well as Chapter 21 ‘Cumulative Effects’. 6.B LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE Legislative Framework 6.4 This section provides a summary of the main planning policies on which the assessment of the likely effects of the Proposed Development on cultural heritage has been made, paying particular attention to policies on design, conservation, landscape and the historic environment. -

AMON WILDS ❋ Invitation, and Should Reply in in a Press Cuttings’ Album in Our Archive There Is One from the Order to Ensure Their Place

Regency Review CONSIDERING THE PAST…FRAMING THE FUTURE THE NEWSLETTER OF THE REGENCY SOCIETY ISSUE 19 NOVEMBER 2007 Murky Waters and Economical Truths y now Members will know that the Society did not The Council went on to say: Bproceed to a Judicial Review of the Council’s planning “Officers answered questions from Members about the Council’s decision on the King Alfred. It was a difficult decision to make role as landowner and whether the developer could have recourse not least because we had delays in obtaining information from to civil remedies if the Council amended its earlier decision. Since the City Council. such questions were raised, officers had a duty to answer them Following the reconfirmation of the Labour administration’s honestly and fairly. In responding to such questions officers decision by the new Conservative-led one, we sought emphasised that while members should be aware of the Council’s further advice from our planning barrister and a top planning wider role as landowner, which related largely to commercial solicitor. We had two principal objectives. These were to see matters, such matters fell outside the planning process. whether we were likely to obtain a ruling in the courts that Members were told that detailed discussions had taken place the previous decision was unsound and, if it was quashed, to with the developer over a long period of time and the developer open the way for a new planning decision, refusing consent. had incurred considerable costs in bringing the proposed scheme Counsel’s advice was that we had an arguable case concerning forward and working it up to its current stage. -

Places of Worship in Georgian and Regency Brighton and Hove’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Sue Berry, ‘Places of worship in Georgian and Regency Brighton and Hove’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XIX, 2011, pp. 157–172 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2011 PLACES OF WORSHIP IN GEORGIAN AND REGENCY BRIGHTON AND HOVE C . – SUE BERRY Between and , the number of places of whereas Lewes had , residents and six parish worship in the flourishing resort of Brighton and churches and Chichester , residents, eight Hove increased from four to about forty, most of which parish churches and a cathedral. The writer believed were built after . The provision for Anglican that Brighton needed at least four more Anglican worshippers before was limited to two old parish churches, calculating that one church would serve churches and a seasonally open chapel of ease. By , people. He claimed that, because of the lack of the total number of buildings and sittings offered by provision by the Church of England, dissenting Nonconformist places of worship had outnumbered groups would flourish, and he drew attention to the those for Anglicans. Their simple buildings were closure of the St James’s Street Chapel (see below), located on cheaper land behind streets or along minor an Anglican free chapel opened by some local streets. But from Anglicans and Nonconformists gentlemen in because neither the Vicar of started building larger places of worship on major Brighton nor the Bishop of Chichester would streets, and some of these striking buildings still survive. support it. Though there were already some fifteen nonconformist places of worship, most of which had rom around the small town of Brighton was free seats, the outburst did not result in any Fsaved from a long period of decline by the immediate change, and in this respect Brighton was development of seaside tourism, attracting increasing typical of other fast-growing towns in which the numbers of wealthy visitors and residents and many Church of England did little to attract worshippers people who provided the wide range of services that until the s. -

Sue Berry, 'A Resort Town Transformed: Brighton C.1815–1840'

Sue Berry, ‘A resort town transformed: Brighton c.1815–1840’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIII, 2015, pp. 213–230 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2015 A RESORT TOWN TRANSFORMED: BRIGHTON c. ‒ SUE BERRY Most of the elegant terraces, squares and crescents in Brighton, Dale accepted the common view that it modern Brighton and Hove were begun between about was a mere fishing village before the Prince of Wales and . The majority were built along the arrived in . More recent research has emphasised sweeping bay on which this resort stands. The first aim that Brighton was not a village but a town, albeit a of this article is to summarise recent research which small and poor one, which was regenerated by expands and revises major parts of Anthony Dale’s seaside tourism from the s. By the time the Fashionable Brighton ‒ ( ). This Prince arrived it was already a popular, rapidly pioneering work formed part of a campaign to save growing resort, aided by good access to London and Adelaide Crescent and Brunswick Town from starting to expand onto agricultural land. demolition and to raise the profile of other coastal Dale thought that the development of the town developments to help protect them. The second aim is to before about had little influence on the location draw attention to the importance of other extensive, and scale of the projects that he described. But deeds and expensive, improvements which were essential to and other sources have since revealed that the the success of a high-quality resort town during this practices used to buy blocks of strips in the period, but which Dale did not discuss. -

1807 20161223 Strategy Docume

Regency Square Community Partnership Regeneration Strategy for Regency Square “Regency Square contains some of the finest examples of Regency architecture in Brighton. Built between 1818 and 1828 on a site known as Belle Vue Field, it is assumed to be the work of Amon Wilds and his son, Amon Henry Wilds, and was financed by Joshua Flesher Hanson as a speculative venture.” www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk Introduction Regency Square occupies a unique position on the Brighton seafront. On an axis with the West Pier, it has been a central part of Brighton life for nearly 200 years – and following the development of our newest seafront attraction - the British Airways i360, looks set to retain this key status into the future. There is however a need to renew and reinvigorate the Square to create a garden worthy of the place it occupies in the city's Regency heritage. The garden enriches the lives of the surrounding community, contributes to the wider city objectives, will be sustainable for the long term and complements the world class BA i360 attraction. As part of the planning consent for the BA i360, 1% of ticket revenue must be provided by BA i360 and used to secure “Environmental Renewal, Maintenance and Improvement Works” within the West Pier Area. It is estimated that this fund will direct around £30k per year to Regency Square garden for the lifetime of the BA i360. It is this resource which will support the regeneration of Regency Square as a coherent whole and underpins this proposal. The aim of this document is to set out a strategy for the regeneration of the square which obtains the best value from identified funding, includes proactive and collaborative engagement with the local Regency Square and wider Brighton and Hove community, and acts as a lever to generate and direct community capital and additional funding and sponsorship resources into the improvement of the square. -

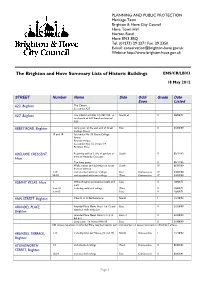

The Brighton and Hove Summary Lists of Historic Buildings ENS/CR/LB/03

PLANNING AND PUBLIC PROTECTION Heritage Team Brighton & Hove City Council Hove Town Hall Norton Road Hove BN3 3BQ Tel: (01273) 29 2271 Fax: 29 2350 E-mail: [email protected] Website http://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk The Brighton and Hove Summary Lists of Historic Buildings ENS/CR/LB/03 18 May 2012 STREET Number Name Side Odd/ Grade Date Even Listed The Chattri, A23, Brighton See under A27 A27, Brighton The Chattri at NGR TQ 304 103, on North of II 20/08/71 land north of A27 Road and east of A23 Lamp post at the east end of Great East II 26/08/99 ABBEY ROAD, Brighton College Street 17 and 19 See under No. 53 Great College Street Pearson House See under Nos 12, 13 and 14 Portland Place Retaining wall to S side of gardens in South II 02/11/92 ADELAIDE CRESCENT, front of Adelaide Crescent Hove Ten lamp posts II 02/11/92 Walls, ramps and stairways on South South II* 05/05/69 front of terrace 1-19 and attached walls and railings East Consecutive II* 24/03/50 20-38 and attached walls and railings West Consecutive II* 24/03/50 1 White Knights and attached walls and East II 10/09/71 ALBANY VILLAS, Hove piers 2 and 4 including walls and railings West II 10/09/71 3 and 5 East II 10/09/71 Church of St Bartholomew North I 13/10/52 ANN STREET, Brighton Arundel Place Mews Nos.11 & 12 and East II 26/08/99 ARUNDEL PLACE, attached walls and piers Brighton Arundel Place Mews Units 2, 3, 4, 8, East of II 26/08/99 8A & 9 Lamp post - in front of No.10 East II 26/08/99 NB some properties on Arundel Place may be listed as part of properties on Lewes Crescent or Arundel Terrace. -

Heritage Statement

Heritage Statement The Heritage Statement is for the applicant or agent to identify the heritage asset(s) that have the potential to be affected by the proposals and their setting. Please read the guidance notes provided at the back of this report to help you fill in the form correctly. https://www.brighton- hove.gov.uk/content/planning/heritage/heritage-statements Appendix 1 relates to the Historic Environment Record (HER) Consultation Report. You must state whether or not supporting data from the HER is required. There are 3 options: • HER report attached (this must be completed by the Historic Environment Record Team) • HER report not considered necessary – email attached from HER • HER report not required by the Local Planning Authority as detailed on the relevant website validation requirements Please tick the relevant box at the back of this form as to which option applies. Both the Heritage Statement and the Historic Environment Record Consultation report (Appendix 1) must be completed in order to meet validation requirements of the Local Planning Authority – tick the boxes on the right hand side below to confirm the sections completed. Note: All fields are mandatory. Failure to fully complete all fields may result in the form not being validated by the Local Planning Authority (LPA). To be completed by the applicant – please tick relevant boxes 1. Heritage Statement completed x 2. Appendix 1 completed 1 Heritage Statement Site name Flat 15, 59-62 regents court Address of site Flat 15 (including postcode) 59-62 regents court Regency Square Brighton BN1 2FF Grid Reference 1. Schedule of Works Please state the type of proposal e.g. -

Davigdor Road, 12, Windlesham Mansions, Hove Historic Building No CA Social Club ID 209 Included on Current Local List

Davigdor Road, 12, Windlesham Mansions, Hove Historic Building No CA Social Club ID 209 Included on current local list Description: A large, 2-3 storey house, with Arts & Crafts influences in its design. Brick with pebbledash render above. Four bays in width; three with gable ends containing mock timber framing. The main entrance is located in the westernmost of the central bays. It is contained within an unusual porch, incorporating such features as a canopy roof, an arched batwing fanlight and stained glass side-lights divided by small stone columns. The two western bays each have a canted bay window with mullioned lead-light windows. The eastern bays also contain mullioned windows, as well as a bow window. Built 1907 by T. Garrett, it was used as a Social Club (the Windlesham Club), with its own bowling green. It was part-converted to flats in 1988, with the remaining converted following the closure of the club. Source: Middleton 2002 A Architectural, Design and Artistic Interest ii A good, well-detailed example of an Arts and Crafts-influenced large house C Townscape Interest ii Not within a conservation area, the building contributes positively to the streetscene, being larger and more imposing than its neighbours F Intactness i The design integrity of the front elevation survives Recommendation: Retain on local list. Dean Court Road, 1-5 (odd), Tudor Cottages, Rottingdean Historic Building Rottingdean Houses ID 44, 211 Not included on current local list Description: Former farm buildings associated with Manor/Court Farm, converted to residential use in the 1930s. The buildings were converted in a ‘Tudorbethan style, similar to that of the listed Tudor Court opposite (also former farm buildings). -

12A Marine Square, Brighton BN2 1DL

12A Marine Square, Brighton BN2 1DL Historic Building Report for Copse Mill Wright March 2021 ii Donald Insall Associates | 12a Marine Square, Brighton, BN2 1DL Contents 1.0 Summary of Historic Building Report 1 2.0 Historical Background 4 3.0 Site Survey Descriptions 19 4.0 Assessment of Significance 45 5.0 Commentary on the Proposals 49 Appendix I - Statutory List Description 58 Appendix II - Planning Policy and Guidance 60 Contact information Sarah Bridger (Senior Historic Buildings Advisor) E: [email protected] T: 020 7245 9888 London Office 12 Devonshire Street London, W1G 7AB www.donaldinsallassociates.co.uk This report and all intellectual property rights in it and arising from it are the property of or are under licence to Donald Insall Associates or the client. Neither the whole nor any part of this report, nor any drawing, plan, other document or any information contained within it may be reproduced in any form without the prior written consent of Donald Insall Associates or the client as appropriate. All material in which the intellectual property rights have been licensed to DIA or the client and such rights belong to third parties may not be published or reproduced at all in any form, and any request for consent to the use of such material for publication or reproduction should be made directly to the owner of the intellectual property rights therein. Checked by PR.. Ordnance Survey map with the site marked in red [reproduced under license 100020449} 1.0 Summary of Historic Building Report 1.1 Introduction Donald Insall Associates was commissioned by Copse Mill Wright in March 2021 to assist them in proposals for the refurbishment and subdivision of a maisonette into two flats on the lower ground and ground floor of 12a Marine Square, Brighton, BN2 1DL. -

Brunswick Town Conservation Area Character Statement.Pdf

Brunswick Town Conservation Area Character Statement Designated : 1969 Extended : 1978 Area: 38.8187 Hectares 95.9211 Acres Article 4 Direction: The Brunswick 'comprehensive' Article 4 direction approved in August 1993 Brunswick 'Minor Works' Direction Painting Article 4 direction (Brunswick Place North) Lansdowne Square (Painting) direction Introduction: The purpose of this document is to describe the history and character of this conservation area in order to provide a context for policies contained in the Development Plan, which will guide future development and enhancements in the area. The statement was approved as Supplementary Planning Guidance on 18th February 1997. Historic Development of the Area : Brunswick Town has been described as one of the finest examples of Regency and early Victorian planning and architecture in the country. Much of the area was designed as a whole by the architect Charles Augustin Busby with Amon Wilds. The spacious elegant houses of Brunswick Square and Terrace were built between 1824 and 1840. The Brunswick Estate also had its own market building, town hall and Commissioners. In 1830, an Act of Parliament was made requiring all houses in Brunswick Square and Terrace and Brunswick Place (South) to be painted regularly and to a uniform colour. This is still a requirement and properties must be painted every five years. Further west, Adelaide Crescent was designed in 1830 by Decimus Burton, but only partly built, and the remainder together with Palmeira Square, was completed to a different design by Sir Isaac Goldsmid in 1850-1860. The result was the bottle shaped layout, with Palmeira Square and the famous floral clock at the top. -

130In the Last 10 Years

Specimen Address, Specimen Town Total planning applications Site plan In the last 130 10 years © Crown copyright and database rights 2020. Ordnance Survey licence 100035207 Planning summary Large Projects Radon 77 searched to 500m page 3 Identified page 19 Small Projects Planning Constraints 49 searched to 125m page 12 Identified page 20 House Extensions 4 searched to 50m Full assessments for other environmental risks are available in other Groundsure searches including Groundsure Review report. Contact Groundsure or your search provider for further details. Ref: Planview_planview_ebaf [email protected] Your ref: GS-TEST 08444 159 000 Grid ref: 531060 104476 Date: 20 January 2020 Specimen Address, Specimen Town Ref: Planview_planview_ebaf Your ref: GS-TEST Grid ref: 531060 104476 Planning summary Planning Applications Using Local Authority planning information supplied and processed by Glenigan dating back 10 years, this information is designed to help you understand possible changes to the area around the property. Please note that even successful applications may not have been constructed and new applications for a site can be made if a previous one has failed. We advise that you use this information in conjunction with a visit to the property and seek further expert advice if you are concerned or considering development yourself. Large Developments Please see page 3 for details of the proposed 77 searched to 500m developments. Small Developments Please see page 12 for details of the proposed 49 searched to 125m developments. House extensions or new builds Please see page 17 for details of the proposed 4 searched to 50m developments. Please note the links for planning records were extracted at the time the application was submitted therefore some links may no longer work. -

Brighton & Hove Open Door 2010 PROGRAMME

1 Brighton & Hove Open Door 2010 9 – 12 September PROGRAMME 180+ FREE EVENTS to celebrate the City’s heritage Contents General Category Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 03-06 My House My Street Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 06-07 Industrial & Craft Heritage Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 07-08 Fashionable Houses Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 08-11 Eco Open Houses Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 11-13 Religious Spaces Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 13-16 Royal Pavilion, Museums & Libraries Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 16-17 Other historic buildings Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 17-18 Learning, Ed. & Training Open Door P. 18-19 Trails/Walks – History & Archaeology Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 19-21 Trails/Walks – Art; Literature and Architecture Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 21-22 Film and Photographic Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 22-24 Archaeology Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 24-26 Especially for young people Open Door and Pre-Booked Events P. 26 REQUESTS Feedback and Appeal P. 26 Brighton & Hove Open Door 2010 Programme 2 About the Organisers Brighton & Hove Open Door is organised annually by staff and volunteers at The Regency Town House in Brunswick Square, Hove. The Town House is a grade 1 Listed terraced home of the mid-1820s, developed as a heritage centre with a focus on the city’s rich architectural legacy. The Town House is supported by The Brunswick Town Charitable Trust, registered UK charity number 1012216.