Heritage-Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOME & Interiors

HOME & interiors KNIGHTSBRIDGE, LONDON Tuesday 21 June 2016 HOME & interiors Ӏ Knightsbridge, London Ӏ 21 June 2016 THIS SALE FEATURES Asian Art, Silver, Clocks, Furniture, and Carpets AT HOME WITH Rita Konig, the interior guru, gives her top tips 23466 HOME & interiors KNIGHTSBRIDGE, LONDON SALE TUESDAY 21 JUNE 2016, 10:00, LOTS 1 – 433 VIEWINGS SUNDAY 19 JUNE 2016, 11.00 - 15.00 MONDAY 20 JUNE 2016, 9.00 - 16.30 VENUE BONHAMS MONTPELIER STREET KNIGHTSBRIDGE LONDON, SW7 1HH CATALOGUE £10 MEET THE TEAM Mark Wilkinson Keara Cornell Head of Sale Senior Sales Coordinator [email protected] [email protected] 020 7393 3855 020 7393 3855 Miles Harrison Ben Law-Smith Silver Asian [email protected] [email protected] 020 7393 3974 020 7393 3842 Nicholas Faulkner Rosa Assennato Carpets Asian Art [email protected] [email protected] 020 8963 2845 020 7393 3883 Thomas Moore Michael Lake Furniture Sculpture, Clocks & Works of Art [email protected] [email protected] 020 8963 2816 020 8963 2813 STORAGE INFORMATION SALE NUMBER 23466 Sold lots, unless marked WT, will remain STORAGE CHARGES PAYMENT in the collections department at Bonhams, For all lots marked WT, and all lots delivered to All charges due to Ward Thomas Knnightsbridge until Tuesday 5th July 2016. Ward Thomas Removals after their two weeks Removals Ltd must be paid by the time of Lots not collected by Tuesday 5th July 2016 will free storage at Knightsbridge, storage and collection from their warehouse. be removed to the warehouse of Ward Thomas handling charges will commence from midnight Removals Ltd where charges will be payable. -

Groundsure Planning

Groundsure Planning Address: Specimen Address Date: Report Date Report Reference: Planning Specimen Your Reference:Planning Specimen Client:Client Report Reference: Planning Specimen Contents Aerial Photo................................................................................................................. 3 1. Overview of Findings................................................................................................. 4 2. Detailed Findings...................................................................................................... 5 Planning Applications and Mobile Masts Map..................................................................... 6 Planning Applications and Mobile Masts Data.................................................................... 7 Designated Environmentally Sensitive Sites Map.............................................................. 18 Designated Environmentally Sensitive Sites.................................................................... 19 Local Information Map................................................................................................. 21 Local Information Data................................................................................................ 22 Local Infrastructure Map.............................................................................................. 32 Local Infrastructure Data.............................................................................................. 33 Education.................................................................................................................. -

SUSSEX. [POST OFFICE Giles Mrs

2906 BRIGHTON. SUSSEX. [POST OFFICE Giles Mrs. 3 Chicl1ester p1. Kemp town Griffith Mrs. 26 Montpeliel"strett Hardy William, 9 Waterloo place GiU Airs. Dunwoody, 28 Prestonvlle.rd Griffiths 81. Pryce, 2 Selborne rd. Hove Hargreaves Rev. Joseph, [Weslepan], Gilpin Mrs. 5 Pre!-tomille terrace Grimble Mrs. Amelia, 1 Portland place 4 Stanford road Glaisyer l\fiss, 45 Gardner street Gritton Mrs. 8 Lewes crescent Harley Miss, 52 Egremont place Glanville Wm. Gordon. 11 Richmnd. rrl Groombrirfge Daniel TJ;}os. Leopold road Harmar Wm. Bycroft, 17 Cbesham pi Glac:kin Rev. John [Baptist], 49 Rose Grounds David, 83 Ditchling rise Harper Edward, 8 Brunswick terrace Hill terrace Grover Samuel John, 8 Shafteshnry rd Harris Charles John, 4: Pelham square • Glayzer Thomas, 96 London road Groves John, 9 Ventnor viis. Cliftonville Harris Henry Edward, 17 Cannon place Glyn Mrs. 22 Brunswick square Grunow Mrs. 2 Belvedere terrace Harris James Sidney, 81 Upper North st Godbold George, 14 Hamilton road Guerin Mrs. 7 Seafield, Cliftonville Harris Miss, 6 Arundel ter. Kemp town Godfree Georg~ Stephen. 65 Preston rd Guillaume Miss,1 Oshorne vils.Cliflonvl Harris 1\Iiss, 66 Lansdowneplace, Hove Godwin Jas. EyleQ, 65 Ditchling rise Guimaraens Mrs. 6 Round Hill crescent HarriR Mrs. 48 Great College street Godwin Mrs. 44 Buckingham road Gunn Alfred, 115 Ditchling rise Harris Mrs. IO Sussex square Goff Miss, IO St. John's terrace, Hove Gnnn Mrs. 4 Se:Jfield, Cliftonvil!e Harris Mrs. 3 Waterloo place Golden Charles, 30 Clifton street Gunn Stephen, 34 East street Harrison Miss, 35 Grand parade Golden Charles, 16 l.:ollege road Gurbs Stephen, 35 Montpelier !'ltreet Harrison Mr~. -

Cadenza Document

Planning & Public Protection Hove Town Hall Norton Road Hove BN3 3BQ WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT1990 PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS & CONSERVATION AREAS) REGULATIONS 1990 TOWN & COUNTRY PLANNING (GENERAL MANAGEMENT PROCEDURE) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2010 (Notice under Article 13 and accompanied by an Environmental Statement where appropriate) PLEASE NOTE that the following applications were registered by the City Council between 25/02/2013 and 03/03/2013 a) Involving Listed Buildings within Conservation Area BRUNSWICK AND ADELAIDE BH2013/00337 2 Brunswick Road Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Installation of 3no external vents to rear elevation. Officer : Helen Hobbs Tel. No.293335 Brunswick Road Dental Practice Dr Florentina Marcu 2 Brunswick Road Hove BN3 1DG BH2013/00339 2 Brunswick Road Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Installation of 3no external vents to rear elevation. Officer : Helen Hobbs Tel. No.293335 Brunswick Road Dental Practice Dr Florentina Marcu 2 Brunswick Road Hove BN3 1DG Page 1 of 21 BH2013/00459 Flat 1 49 Brunswick Square Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Installation of air vent to front elevation. (Retrospective). Officer : Mark Thomas Tel. No.292336 Dr Robert Towler Hatchwell & Draper FLAT 1 The Agora 49 Brunswick Square Ellen Street Hove Hove BN3 1EF BN3 3LS BH2013/00510 Flat 53 Embassy Court Kings Road Brighton REGENCY SQUARE Internal alterations including removal of airing cupboard from bathroom, moving door to master bedroom, formation of double doors between drawing room and living and drawing room and kitchen. Officer : Christopher Wright Tel. No.292097 Paul Dennsion Andrew Birds Flat 53 76 Embassy Court Embassy Court Kings Road Kings Road Brighton Brighton BN1 2PY BN1 2PX BH2013/00543 Flat 8 18-19 Adelaide Crescent Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Internal alterations to layout of flat. -

Newsletter 12 July 2019

Newsletter 12 July 2019 A message from Barnardo’s Choral the Headmaster Celebration On Monday 24th June, we took thirty-five children from the Dear Parents and Carers, Nightingale and Lark Choirs to perform at Westminster Central Hall, London. As we near the end of our This was a Massed Choir event organised by the charity Barnardo’s. busiest term The Choirs worked very hard to learn all the music, having extra of my second practises most weeks since January. year, I would The coach left school at 8:15 and returned us to school at 23:30. like to take this There was a long day of rehearsals followed by a lovely concert in the opportunity to evening. Among the many highlights of the day, we enjoyed lunch in thank you all St James’ park, rolled down a grassy verge and saw a film crew with for your continued support and to Amanda Holden! We were all so proud of the children who behaved wish you all a very relaxed and impeccably, and sang their hearts out. Thanks go to the many parents restful Summer break. and carers who attended the concert and to Mr Ingrassia, Miss Thompsett and Mrs Green for their teamwork. I very much look forward Reporter: Mrs Gallant to welcoming you back in September. Best wishes, Preparing children for life General Information Year 6 Fiver Challenge Year 6 has now completed its Fiver Challenge and I would like to thank you all for any support you have given the children with their enterprises. The totals have now been counted and a grand sum of £500.98 was raised. -

Vebraalto.Com

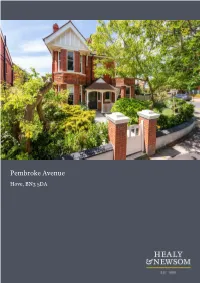

Pembroke Avenue Hove, BN3 5DA Pembroke Avenue, Hove, BN3 5DA A rare opportunity to acquire a unique, substantial Edwardian house; the only detached property occupying a corner plot in one of Hove's most desirable tree-lined avenues. Beautifully presented, having been extensively and sympathetically renovated to enhance the integrity of the house, this elegant family home has also been impeccably designed throughout with the perfect blend of tasteful, period styling and modern living. With five bedrooms, two reception rooms, an office/craft room, a spacious kitchen breakfast room with separate utility room, two bathrooms with two additional cloakrooms. Enjoying significant wrap-around gardens; a well thought out space with a dedicated allotment and green house, as well as a standalone garage and off-street parking. Location A separate utility room has been created to meet washing and laundry needs. Situated in a quiet, tree lined street, Pembroke Avenue is within a conservation area that preserves the period elegance and charm of this exceptional location The ground floor cloakroom features a Lefroy Brooks wash basin with nickel with its wide range of Edwardian houses. This area reflects the status of taps and a matching high-level toilet, with fleur-di-lis obscured sash window. wealthier individuals of the era and the properties here are varied in design but all are opulent, grand homes with ornate architecture, elegant proportions and On to the first floor and situated at half landing level is the most stunning intricate detailing; they were built to be admired, with this property being one of ornithological themed, original stained glass window that is almost ecclesiastic the first constructed, occupying a corner plot on the junction of Pembroke in style, and proportion. -

Ladies Mile Road, Mile End Cottages, 1-6 Historic Building No CA Houses ID 75 & 275 Not Included on Current Local List

Ladies Mile Road, Mile End Cottages, 1-6 Historic Building No CA Houses ID 75 & 275 Not included on current local list Description: Brown brick terrace of six cottages, with red brick dressings and a clay tile roof. Two storey with attic; a matching dormer window has been inserted into the front roof slope of each property. The terrace is set at right angles to the road, at the western end of Ladies Mile Road, a drove road which became popular as a horse-riding route in the late 19th century. The properties themselves are of late 19th century date. They are first shown on the c.1890s Ordnance Survey map. A complex of buildings is shown to the immediate west of the cottages on this map. Arranged around a yard, this likely formed agricultural buildings or service buildings associated with Wootton House. The architectural style and physical association of the cottages to these buildings and the drove road suggests they may have formed farmworkers’ cottages. A Architectural, Design and Artistic Interest ii A solid example of a terrace of worker’s cottages B Historic and Evidential Interest ii Illustrative of the agricultural origins of Ladies Mile Road as a drove road and associated with the historic agricultural village of Patcham. C Townscape Interest ii Outside of Patcham Conservation Area, but associated with its history and contributes positively to the street scene F Intactness i Although some of the windows have been replaced, and there are modern insertions at roof level (particularly to the rear), the terrace retains a sense of uniformity and completeness Recommendation: Include on local list Lansdowne Place, Lansdowne Place Hotel, Hove Historic Building Brunswick Town Hotel ID 128 + 276 Not included on current local list Description: Previously known as Dudley Hotel. -

1. NOTICE Is Hereby Given That Brighton & Hove

BRIGHTON AND HOVE CITY COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 TEMPORARY TRAFFIC ORDER – (BRIGHTON MARATHON) (TEMPORARY TRAFFIC REGULATION) ORDER 2018 1. NOTICE is hereby given that Brighton & Hove City Council intend not less Brewer Street Lansdowne Place Richmond Parade Wish Road Wyndham Street York Place than seven days from the date of this notice to make an Order pursuant to Brills Lane Langdale Gardens Richmond Place Worcester Villas York Hill powers in Section 16A to 16C of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 as amended which when it comes into force will have the following effect:- Brittany Road Langdale Road Richmond Terrace SCHEDULE 2 Broad Street Leicester Villas Robert Street (a) No person shall cause or permit any vehicle that is not participating in, Aquarium Roundabout Kings Esplanade Ovingdean Road or connected with, the Marathon to proceed in, exit from, or turn into Brunswick Square Lewes Crescent Rock Place (between Greenways any of the lengths of road specified in Schedule 1 to this Order between Basin Road South Kings Road Burlington Street Lewes Road Roedean Lane and Longhill Road) 06:00 hours on Sunday 15th April 2018 and 22:00 hours on Sunday Boundary Road Kingsway (between 15th April 2018 except upon the direction or with the permission of Caledonian Road Little East Street Roedean Road Kings Road and Wharf Pavilion Parade a police constable in uniform or a uniformed marshal. Castle Square Camelford Street Little Preston Street Roman Road Road) Preston Circus (b) No parking, waiting, loading or unloading of a vehicle is to take place Cannon Place London Road Rookery Close Church Road (between on any of the lengths of road specified in Schedule 2 to this Order and Lewes Road Preston Drove (between Grand Avenue and Hove which constitute the Brighton Marathon Route between the hours of Carlisle Road Lovers Walk Rose Hill Preston Park Avenue and Street) London Road 18:00hrs on Saturday 14th April 2018 and 22:00hrs on Sunday Castle Square Lower Rock Gardens Rose Hill Terrace Preston Road) 15thApril 2018. -

Royal Crescent Brighton (C.1796–1805) – an Early Seaside Crescent’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Sue Berry, ‘Royal Crescent Brighton (c.1796–1805) – an early seaside crescent’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXV, 2017, pp. 237–246 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2017 ROYAL CRESCENT BRIGHTON (c.1796–1805) – an eaRLY SEASIDE CRESCENT SUE BERRY Brighton’s Georgian legacy includes some distinctive visual contribution to Brighton’s townscape, and and elegant projects, one of the most impressive of newly-discovered evidence from Court cases provides which is Royal Crescent. Built between c.1796 and valuable information about building costs, rare in 1805, this speculative project of fourteen terraced Brighton, and insights into a developer’s desire to houses faces the sea on Brighton’s eastern cliffs. Its control quality, in this case the provision of superior façade of black mathematical tiles makes a striking water closets. The Royal Pavilion facing east overlooking the Steine Byam House Belle Vue House Royal Crescent Fig. 1. Marchant’s map of Brighton in 1808 showing the location of Royal Crescent. (Private Collection) THE GEORGIAN GROUP JOURNAL VOLUME XXV ROYAL CRESCENT BRIGHTON ( c . 1 7 9 6 – 1 8 0 5 ) – AN EARLY SEASIDE CRESCENT Fig. 2. Royal Crescent today from the east. (Author) etween the late 1770s and the mid-1820s there soldiers. The government decided to garrison the Bwas a building boom in Brighton, during which town because the shallow water and gently shelving Royal Crescent, still a landmark on the eastern foreshore, characteristic of Brighton and the bay cliffs, was built (Fig. 1). The demand for houses to the west of the town, were not only convenient and services that drove the resort’s expansion for bathing machines, but could also enable troops out of its old boundaries onto the surrounding to embark and disembark easily. -

Vebraalto.Com

Robert Street, North Laine, Brighton, BN1 4AH 3 1 1 1 D Guide Price £600,000 - £625,000 oakleyproperty.com • Period House • North Laine Conservation Area • Beautifully Presented • Open Plan Living Space • Bespoke Fitted Kitchen • Three Bedrooms • Modern Fitted Shower Room • Gas Central Heating • Lovely Rear Garden • Total Floor Area 91 SQ.M / 980 SQ.F Tel: 01273 688881 The Property A very attractive period house located on a sought after street in the popular North Laine conservation area. The well proportioned accommodation can be approached via two street entrances, is arranged over three floors and comprises on the lower ground floor; open plan living space including a bespoke fitted kitchen supplied by local company ‘North Road Timber’. The ground floor is arranged with a sizeable bedroom, hallway, modern fitted shower room with WC and a very useful separate WC. On the first floor is a landing with a skylight and two further good size bedrooms. Outside to the rear of the house is a delightful walled garden with raised beds and exposed bungaroosh feature wall. The Location Robert Street is situated in the heart of the vibrant North Laine conservation area of central Brighton, and is ideally located for Brighton Mainline Railway Station (0.3 miles). Local cafes, restaurants, shops, retail and entertainment facilities are right on the doorstep; including Brighton Komedia (0.1 miles), the Royal Pavilion (0.3 miles), Brighton Dome (0.2 miles), seafront (0.7 miles) and Brighton Pier (0.7 miles). Brighton Mainline Railway Station, many bus routes closely located, the A23 & A27 provide easy access around Brighton, Hove and into London. -

Priyal,E HESJ DENTS. O.AL 685

15UI91:5BX, J PRIYAl,E HESJ DENTS. O.AL 685 :Burrows Mrs. Yewhurst, Spithurst, Ba~ Bussey W. E. 15 Aymer rd. Hove,Brightn Bu.·don Viscount P.C., G.C.M.G. New combe, Lewes Bussy Baroness de, 1 The Marina,Brighton timber Place, Hassocks; & li Bucking Burrows Ogden Hoffman, 21 Brunswick road, Worthing ham gate 8 W & Athenreum & Brookd's square, Hove, Brighton Butcher Rev. Louis Betnard B.A. 33 Vie· clubs S W, London .Burstow .A.bram, 27 Grange road, Lewes toria drive, EastbournP. Buxton Miss, 45 Church rd. Burgess Hill Burstow C.7Gladstone ter.Lewes rd.Brghtn Butcher Oecil Frank, 20 Worcester villas, Bu.x:ton Travers, View field, Beacon road, Burstow Charles Henry, Westlands, King';; Hove, Brighton Crowborough road, Horsham Butcher Daniel, 4 Ratton rd. Eastbourne Buzzard Rodney, Hillcote, Buxted,Uckfield. Burstow Mrs. Harewood, Alexandra road, Butcher Frederick James, Oalncourt, New Byam Misses, Avenel,Richmond rd.Wrthng Burgess Hill Church road, Portslade, Brighton Byass Ed.gar M.B. 2 Lancaster villas, Old :Burstow W. J. Fairfield, St. Lawrencl' Butcher George, Ashington, Pulborough Shoreham road, Brighton avenue, West Tarring, Worthing Butcher George Stephen, Aldwich, Rugby Byass Miss, Maltravers street, Arnndel .Burt Rev. Emile, St. John's presbytery, road, West Worthing Byerley Mrs. 25 Rugby rd. Preston,Brghtn Heron's Ghyll, U ckfield Butcher W. J. Delgany, Heene rd. West Hygott Rog-er, The Poplars, Beckley Burt A. H. 23 Palmeira ~q.Hove,Brightor. Worthing Byham Geo. Middle hth.Graffham,Petwrth Burt A. T. 26 Cantelupe rd. E. Grinstead Butcher Waiter, Ecclesden manor, Ang Byham Miss, Newstead, Easebrne.Midhrst .Bnrt Alfred, Holmlea, Yapton, Arundel mering, Worthing Ryles Mrs. -

AMON WILDS ❋ Invitation, and Should Reply in in a Press Cuttings’ Album in Our Archive There Is One from the Order to Ensure Their Place

Regency Review CONSIDERING THE PAST…FRAMING THE FUTURE THE NEWSLETTER OF THE REGENCY SOCIETY ISSUE 19 NOVEMBER 2007 Murky Waters and Economical Truths y now Members will know that the Society did not The Council went on to say: Bproceed to a Judicial Review of the Council’s planning “Officers answered questions from Members about the Council’s decision on the King Alfred. It was a difficult decision to make role as landowner and whether the developer could have recourse not least because we had delays in obtaining information from to civil remedies if the Council amended its earlier decision. Since the City Council. such questions were raised, officers had a duty to answer them Following the reconfirmation of the Labour administration’s honestly and fairly. In responding to such questions officers decision by the new Conservative-led one, we sought emphasised that while members should be aware of the Council’s further advice from our planning barrister and a top planning wider role as landowner, which related largely to commercial solicitor. We had two principal objectives. These were to see matters, such matters fell outside the planning process. whether we were likely to obtain a ruling in the courts that Members were told that detailed discussions had taken place the previous decision was unsound and, if it was quashed, to with the developer over a long period of time and the developer open the way for a new planning decision, refusing consent. had incurred considerable costs in bringing the proposed scheme Counsel’s advice was that we had an arguable case concerning forward and working it up to its current stage.