Infrastructure Owner Operators Guiding Principles for Connected Infrastructure Supporting Cooperative Automated Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

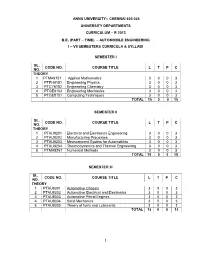

Anna University:: Chennai 600 025 University Departments Curriculum – R 2013 B.E. (Part – Time) – Automobile Engineering

ANNA UNIVERSITY:: CHENNAI 600 025 UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS CURRICULUM – R 2013 B.E. (PART – TIME) – AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING I – VII SEMESTERS CURRICULA & SYLLABI SEMESTER I SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTMA8151 Applied Mathematics 3 0 0 3 2 PTPH8151 Engineering Physics 3 0 0 3 3 PTCY8152 Engineering Chemistry 3 0 0 3 4 PTGE8153 Engineering Mechanics 3 0 0 3 5 PTGE8151 Computing Techniques 3 0 0 3 TOTAL 15 0 0 15 SEMESTER II SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTAU8201 Electrical and Electronics Engineering 3 0 0 3 2 PTAU8202 Manufacturing Processes 3 0 0 3 3 PTAU8203 Measurement System for Automobiles 3 0 0 3 4 PTAU8204 Thermodynamics and Thermal Engineering 3 0 0 3 5 PTMA8251 Numerical Methods 3 0 0 3 TOTAL 15 0 0 15 SEMESTER III SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTAU8301 Automotive Chassis 3 0 0 3 2 PTAU8302 Automotive Electrical and Electronics 3 0 0 3 3 PTAU8303 Automotive Petrol Engines 3 0 0 3 4 PTAU8304 Solid Mechanics 3 0 0 3 5 PTAU8305 Theory of fuels and Lubricants 3 0 0 3 TOTAL 15 0 0 15 1 SEMESTER IV SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTAU8401 Automotive Diesel Engines 3 0 0 3 2 PTAU8402 Automotive Transmission 3 0 0 3 3 PTAU8403 Two and Three Wheeler Technology 3 0 0 3 4 PTPR8351 Kinematics and Dynamics of Machines 3 0 0 3 PRACTICAL 5 PTAU8411 Automotive Engine and Chassis Components 0 0 3 2 Laboratory TOTAL 12 0 3 14 SEMESTER V SL. -

The Impact of Automated Transport on the Role, Operations and Costs of Road Operators and Authorities in Finland

The impact of automated transport on the role, operations and costs of road operators and authorities in Finland EU-EIP Activity 4.2 Facilitating automated driving Risto Kulmala, Juhani Jääskeläinen, Seppo Pakarinen Traficomin tutkimuksia ja selvityksiä Traficoms forskningsrapporter och utredningar Traficom Research Reports 6/2019 Traficom Research Reports 6/2019 Julkaisun päivämäärä 12.3.2019 Julkaisun nimi The impact of automated transport on the role, operations and costs of road operators and authorities in Finland (Automaattiajoneuvojen vaikutukset tienpitäjien ja viranomaisten rooliin, toimintaan ja kustannuksiin Suomessa) Tekijät Risto Kulmala, Juhani Jääskeläinen, Seppo Pakarinen Toimeksiantaja ja asettamispäivämäärä Liikennevirasto ja Trafi 22.3.2018 Julkaisusarjan nimi ja numero ISSN verkkojulkaisu) 2342-0294 Traficomin tutkimuksia ja selvityksiä ISBN (verkkojulkaisu) 978-952-311-306-0 6/2019 Asiasanat Automaattiajaminen, tieliikenne, automaattiauto, vaikutus, tienpitäjä. viranomainen, rooli, kustannukset, toiminta, Suomi Tiivistelmä Tämä kansallinen tutkimus tehtiin osana työpakettia ”Facilitating automated driving” EU:n CEF- ohjelman hankkeessa EU EIP keskittyen viiteen korkean tason automaattiajamisen sovellukseen: moottoritieautopilotti, automaattikuorma-autot niille osoitetuilla väylillä, automaattibussit sekaliikenteessä, robottitaksit sekä automaattiset kunnossapito- ja tietyöajoneuvot. Raportti kuvaa automaattiajamiseen liittyvät säädöspuitteet ja viranomaisstrategiat eri puolilla maailmaa ja etenkin Euroopassa. Tutkimus -

Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles for Everyday Commute

U.S. Department of Transportation NOFO # 693JJ319NF00001 Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles For Everyday Commute Submitted by: University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA Albemarle County, VA JAUNT Inc. Sonny Merryman, Inc. Charlottesville/Albemarle, VA Evington, VA Perrone Robotics, Inc. ARBOC Specialty Vehicles Crozet, VA Middlebury, IN Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles For Everyday Commute – Project Narrative and Technical Approach University_of_Virginia_Part1 U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington DC 20590 Attn: Sarah Tarpgaard, HCFA-32 Dear Ms. Tarpgaard: We are excited to respond to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Automated Driving System Demonstration Grant (NOFO Number 693JJ319NF00001) with our enclosed proposal entitled: SAVvy Mobility - Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles For Everyday Commute submitted by the University of Virginia in collaboration with JAUNT Inc, Perrone Robotics Inc., Albemarle County, VA, Sonny Merryman, and ARBOC. We are requesting a total budget of $10M for a demonstration period of 24 months (Sep 2019-Aug 2021). Automated vehicles are rapidly becoming significant components of our nation’s critical infrastructure. While they hold promise for considerable benefits, they also bring with them urgent safety-critical challenges that must be addressed. In addition, as journeys become fully automated, the experience itself will need to become more accessible to all in our population. The safety, mobility, and economic benefits of highly automated vehicles should be accessible to everyone, and everywhere. The majority of automated driving demonstrations to date have focused on operation and impact in urban settings, with the testing of automated cab services. The perspective of the proposed demonstration is much broader: Automated transit vehicles could be the key to catalyzing the mobility for people living in small and medium sized suburban areas. -

Thesis Cyber Security Consumer Used Connected

Multi actor roadmap to improve cyber security of consumer used connected cars Cyber Security Academy Executive Cyber Security program Drs. Herbert Leenstra S1727834 Telephone number: 06-12946726 E-mail: [email protected] Date of submission: 03-01-2017 Supervisor university: Prof. dr. ir. Jan van den Berg Prof. dr. Bert van Wee Abstract The automotive industry will introduce the autonomous car into the consumer market in the near future. At this moment, several forms of connected cars are introduced. These connected cars present the current state of the art on the path to the ultimate goal of the automotive industry: the consumer used autonomous car. Prior research shows that consumers have several concerns on the use of connected and autonomous cars. The system security of the connected car is one of these concerns. There are currently 7 million consumer used cars in possession of Dutch citizens. Consumer trust is key for a successful introduction of connected – and autonomous cars into the consumer market. These concerns have to be addressed by the automotive industry in order to successfully introduce the autonomous car. When we compare the consumer concerns with the actions of the automotive industry, it becomes clear that the security concern is currently not properly addressed. This threatens the successful introduction of autonomous cars in the future. This research presents a multi actor roadmap which indicates what actions each actor in the automotive industry can take to address and improve the security of connected cars. In order to do this we show that there are technical security threats on the current implementation of connected cars. -

Plug In, Charge Up, Drive Off by Douglas L

Plug In, Charge Up, Drive Off by Douglas L. Smith There’s one simple, obvious way to help minimize them, says a group of Caltech This zippy two-seater goes alums: battery power. from zero to 60 in 3.6 sec- Electric cars flopped onds, and has a top speed in the ’70s, as the lead-acid batteries that of 100 miles per hour. It’s cranked the starters on an electric car that, even our station wagons just more remarkably, can drive weren’t up to the job. from Los Angeles to Las They were (and are) big and heavy, and didn’t Vegas without needing hold that much juice; recharging. Designed by much of what they Alan Cocconi (BS ’80) with did store was turned some styling tips from Art into heat by inefficient power controllers. Center College of Design Consequently, elec- student Scott Sorbet, who tric cars ran like they now works for Ford, the were powered by tired hamsters. They didn’t go very far, and they took an t runs on the same Well, here we are 30-odd years after the Great ZERO Energy Crisis. We’re importing more oil than eternity to recharge. high-energy-density batter- ever, gasoline prices are once again going through That was then. You can curse all you want at ies that power your laptop. the roof, and there’s still turmoil in the Middle those pinheads whose cell phones ring in theaters, East. So what’s different this time around? Two but the explosion in laptops, PDAs, cell phones, things: This time, there really is an energy crisis. -

Delft University of Technology a Conceptual Model to Explain, Predict, and Improve User Acceptance of Driverless 4P Vehicles

Delft University of Technology A conceptual model to explain, predict, and improve user acceptance of driverless 4P vehicles Nordhoff, Sina; van Arem, Bart; Happee, Riender Publication date 2016 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Published in 2016 TRB 95th Annual Meeting Compendium of Papers Citation (APA) Nordhoff, S., van Arem, B., & Happee, R. (2016). A conceptual model to explain, predict, and improve user acceptance of driverless 4P vehicles. In 2016 TRB 95th Annual Meeting Compendium of Papers [16-5526] Washington, DC, USA: Transportation Research Board (TRB). Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. 1 1 A Conceptual Model to 2 Explain, Predict, and Improve 3 User Acceptance of Driverless Vehicles 4 5 6 Sina Nordhoff 7 Department of Transport & Planning 8 Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences 9 Delft University of Technology -

Inspiring Curiosity IT WAS MY PRIVILEGE to Spend Days in China at the Website for This Project Listed on the Left

DIALOGUE dean’s notes Inspiring Curiosity IT WAS MY PRIVILEGE to spend days in China at the website for this project listed on the left. While and Korea this summer visiting universities with in Beijing, I asked our students how their lab meet - which the College has relationships, as well as meet - ings were going, and Justin pointed out that chemi - ing our large group of wonderful alumni in those cal formulas are the same everywhere. Similarly, Xi - countries. But of all those I met —university presi - aowen writes on his blog: “Chemistry =Chem –is –try.” dents, provosts, and faculty members, among others International understanding is certainly all about —the most memorable were: Tiffany Chen, Justin trying, and that begins with the recognition of the Lomont, Brian O’Keefe, Wei Wang, Xiaowen Feng, things we have in common with others such as the Xiaoxue Zhou, and Yiran Shen. These seven extraor - scientific method. It is the goal —indeed duty —of dinary young people are undergraduate chemistry liberal arts colleges to inspire a curiosity for all students from LSA and Peking University in Beijing things human. And when chemistry majors with no (PKU ), and they are the pioneers in a remarkable ex - background in Chinese studies jump at the chance change program we launched this summer with the to study chemistry in Beijing, we have succeeded. Arthur F. Thurnau help of the National Science Foundation, the Drey - It was the same kind of curiosity and pioneering Professor, Professor of History, fus Foundation, and generous alumni such as Rich spirit that led early leaders of the University to and Dean Rogel (’ ) and his wife, Susan. -

Conference Program 26 - 30 May 2019 Mantra on View, Surfers Paradise Driver Management and Training Portal

2019 ATIA International Taxi Conference Conference Program 26 - 30 May 2019 Mantra on View, Surfers Paradise Driver Management and Training Portal Compatible On All Web Accessible Devices Rate Drivers Performance Out Of 5 Stars Real Customer Feedback Acceptance & Reliability Rates Number Of Jobs Accepted Vs. Declined Driver’s Overall Fleet Ranking Ratings On Punctuality and Quality www.mtidispatch.com NORTH AMERICA | EUROPE | AUSTRALIA | NEW ZEALAND CONTENTS 3 ATIA International Taxi Conference 26 - 30 May 2019 Mantra on View Gold Coast, QLD Contents 4 President’s Welcome 5 General Information 6 2019 Sponsors 10 Exhibitor Floor Plan 11 Exhibitor Contact Information 12 Conference Program 13 Business Program Monday 14 Social Program Monday 15 Business Program Tuesday 16 Social Program Tuesday 17 Business Program Wednesday 18 Social Program Wednesday 19 Combined Outing 20 Exhibitor Details 25 Speaker Profile 34 Gold Coast Attractions 35 Wine and Dine 4 PRESIDENT’S WELCOME President’s Welcome Another year has passed, and I am honoured to wel- come delegates back to the Gold Coast for this year’s ATIA International Taxi Conference. I trust that most at- tendees have been looking forward to the opportunity to catch up with friends and colleagues from interstate, I know I certainly am excited to see everyone again. For those of you escaping the colder climates, as the saying goes, Queensland is beautiful the one day, per- fect the next, is particularly true for the beautiful Gold Coast. As some of you may have experienced last year, Surfers Paradise is the perfect place to mix business with pleasure as we discuss issues of strategic impor- tance to our industry while having a good time. -

International Evaluation of Public Policies for Electromobility in Urban Fleets International Evaluation of Public Policies for Electromobility in Urban Fleets

International Evaluation of Public Policies for Electromobility in Urban Fleets International Evaluation of Public Policies for Electromobility in Urban Fleets Study prepared by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) requested by GIZ (German Agency for International Cooperation) and the Ministry of Industry, Foreign Trade and Services (MDIC). Authors: Peter Slowik Carmen Araujo Tim Dallmann Cristiano Façanha November 2018 FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL Presidency of the Republic Michel Temer Ministry of Industry, Foreign Trade and Services Marcos Jorge de Lima Secretariat of Industrial Development and Competitiveness Igor Nogueira Calvet Director of the Department of Industries for Mobility and Logistic – DEMOB Margarete Gandini Technical Support Cooperação Alemã para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável por meio da Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH National Director Michael Rosenauer Project Coordinator Jens Giersdorf COORDINATION AND EXECUTION Coordination and operation team Text review and translation Igor Calvet, Margarete Gandini, Ricardo Zomer, Gustavo Victer, Ana Terra Thomas Caldellas (MDIC), Bruno Carvalho, Fernando Fontes, Jens Giersdorf e Marcos Costa (GIZ). Cover and graphical project João Neves Auhtors Peter Slowik, Carmen Araujo, Tim Dallmann e Cristiano Façanha Layout Barbara Miranda Technical coordination Cristiano Façanha and Marcos Costa PUBLISEHD BY Projeto Sistemas de Propulsão Eficiente – PROMOB-e (Projeto Technical review de Cooperação Técnica bilateral entre a Secretaria de Marcos Costa (GIZ) Desenvolvimento e Competitividade Industrial – SDCI/MDIC e Bruno Carvalho (GIZ) a Cooperação Alemã para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável (GIZ) Ricardo Zomer (MDIC) CONTACTS SDCI/Ministério da Indústria, Comércio Exterior e Serviços Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit Esplanada dos Ministérios BL J - Zona Cívico-Administrativa, (GIZ) GmbH CEP: 70053-900, Brasília - DF, Brasil. -

Look Both Ways: Intersections of Past and Present in the Shaping of Relations Between Cyclists, Pedestrians, and Driverless Cars

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 9-10-2019 Look Both Ways: Intersections Of Past And Present In The Shaping Of Relations Between Cyclists, Pedestrians, And Driverless Cars Davi Aragão Rocha University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Rocha, Davi Aragão, "Look Both Ways: Intersections Of Past And Present In The Shaping Of Relations Between Cyclists, Pedestrians, And Driverless Cars" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7837. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7837 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. LOOK BOTH WAYS: INTERSECTIONS OF PAST AND PRESENT IN THE SHAPING OF RELATIONS BETWEEN CYCLISTS, PEDESTRIANS, AND DRIVERLESS CARS By Davi Aragão Rocha A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Faculty of Law in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Laws at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada © 2019 Davi Aragão Rocha LOOK BOTH WAYS: INTERSECTIONS OF PAST AND PRESENT IN THE SHAPING OF RELATIONS BETWEEN CYCLISTS, PEDESTRIANS, AND DRIVERLESS CARS By Davi Aragão Rocha APPROVED BY: ____________________________________________ M. -

1 a New Approach to Modeling Large-Scale Alternative

1 A NEW APPROACH TO MODELING LARGE-SCALE ALTERNATIVE FUEL AND VEHICLE TRANSITIONS by Joel Bremson, [email protected], UC Davis, Alan Meier, [email protected], Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, C.-Y. Cynthia Lin, [email protected], UC Davis, Joan Ogden, [email protected] ,UC Davis Corresponding Author: Joel Bremson – [email protected] -530-219-8446 Abstract A large-scale transition to alternative fuels and vehicles will be challenging. New modeling approaches are necessary to supplement existing models, such as MARKAL. One promising approach is simulation gaming. Simulation gaming has been used extensively in many fields, most conspicuously in military applications, to provide insights into the dynamics of uncertain processes. A large-scale alternative fuel and vehicle transition themed game was developed to explore the potential of this approach. Preliminary results of game play suggest a possible counter-intuitive dynamic: high energy prices can discourage wide scale adoption of alternative fueled vehicles due to the fact that increased fuel costs reduce consumers’ ability to pay for more costly alternative vehicle technologies. 2 Introduction A major transition to alternative fuels and vehicles must be undertaken if we are to drastically reduce GHG emissions and oil dependence. New fuels including electricity, hydrogen, and biofuels will have to achieve mass-market acceptance and capacity along with their corresponding drivetrains. The LDV segment has been petroleum fueled from practically the beginning of the 20th century. A massive inertia of infrastructure and ingrained habit surrounding conventional internal combustion drivetrains must be overcome; an industrial transformation on a scale that has never before been attempted. -

Rulemaking Hearing Rule(S) Filing Form

The Department of Agriculture filed a letter of clarification about this rule filing on 11/4/14 The Department indicated that the language in the rule filing 09-06-14 is correct and that the redline version should not be considered when amending Chapter 0080-05-12. Go to page 54 to see the clarification letter. Department of State For Department of State Use Only Division of Publications 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 8th Floor Snodgrass/TN Tower Sequence Number: o?l ~ ()(p ~-I'+ Nashville, TN 37243 Phone: 615-741-2650 Rule ID(s): Sl9 (p , Fax: 615-741-5133 File Date: Cj -~ l.f ·- I 'i Email: [email protected] Effective Date: i 2-B- I '-t Rulemaking Hearing Rule(s) Filing Form Rulemaking Hearing Rules are rules filed after and as a result of a rule making hearing. T.C.A. § 4-5-205 . A-gency/Board/Com-mission:-. Tennessee Department of Agriculture -- -- -- :-- __ - Division:-. Consumer-and Industry Services ___________________________------. ~---------Contact Person:-TK~bavid Waddell ___________ --------------------------------------------- ----~-----=-~~~ Ad~ress: ' Po Box 4Q62?, Nashviii~"-Ienne_f5-se~------------------------- ------------ ___Zip: ~204 _____________________________________________________ _ Phone: • 615-837-5331 ----- -- ----- ------- --- - -- -- -- ------- - __ _Ema~ davi(j.wadd_ell@_tQ._g.,__o_v ___________________________________ Revision Type (check all that apply): X Amendment New Repeal Rule(s) Revised (ALL chapters and rules contained in filing must be listed here. If needed, copy and paste additional tables