Models for Data Sharing and Governance for Automated Vehicles and Shared Mobility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Make Use of Data in a Car: Connected Cars, Payment Tech, Analytics, and Other Opportunities

HOW TO MAKE USE OF DATA IN A CAR: CONNECTED CARS, PAYMENT TECH, ANALYTICS, AND OTHER OPPORTUNITIES Andrew Ray David Monteiro May 13, 2020 Tess Blair @MLGlobalTech © 2018 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Morgan Lewis Automotive Hour Webinar Series Series of automotive industry focused webinars led by members of the Morgan Lewis global automotive team. The 10-part 2020 program is designed to provide a comprehensive overview on a variety of topics related to clients in the automotive industry. Upcoming sessions: JUNE 10 | Employee Benefits in the Automotive and Mobility Context JULY 15 | Working with, or Operating, a Tech Startup in the Automotive and Mobility Sectors AUGUST 5 | Electric Vehicles and Their Energy Impact SEPTEMBER 23 | Autonomous Vehicles Regulation and State Developments NOVEMBER 11 | Environmental Developments and Challenges in the Automotive Space DECEMBER 9 | Capitalizing on Emerging Technology in the Automotive and Mobility Space 2 Table of Contents Section 01 – Introductions Section 02 – Market Overview Section 03 – Data Acquisition and Use Section 04 – Regulatory and Enforcement Risks 3 SECTION 01 INTRODUCTIONS Today’s Presenters Andrew Ray David Monteiro Tess Blair Washington, DC Dallas Philadelphia Tel +1.202.373.6585 Tel +1.214.466.4133 Tel +1.215.963.5161 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 5 SECTION 02 MARKET OVERVIEW 7 Market Overview • 135 million Americans spend 51 minutes on average commuting to work five days a week. • Connected commerce experience represents a $230 billion market. • Since 2010, investors have poured $20.8 billion into connectivity and infotainment technologies. Source: “2019 Digital Drive Report,” P97 / PYMNTS.com; “Start me up: Where mobility investments are going,” McKinsey & Company. -

Connected Car

Connected Car [email protected] 1 Confidential – © 2019 Oracle Internal/Restricted/Highly Restricted I've always been asked, „What is my favorite car?” and I've always said „The next one”. Carroll Shelby Source: Wikipedia 2 Confidential – © 2019 Oracle Internal/Restricted/Highly Restricted Connected Car or Autonomous Car Connected vehicles can exchange information wirelessly with other vehicles and infrastructure, but also with the vehicle manufacture or third-party service providers. Automated vehicles, on the other hand, are vehicles in which at least some aspects of safety- critical control functions occur without direct driver input. 3 Confidential – © 2019 Oracle Internal/Restricted/Highly Restricted The Race is On to Capture In-Vehicle Commerce By 2020, there will be 250 Million connected vehicles on the road globally Gartner & Connected Vehicle Trade Association 82% of new cars will be connected to Internet in 2021 Business Insider Connected car commerce will zoom to $265 billion by 2023 Juniper Research Automakers align with tech firms Voice technology will prevail Source: Business Insider 4 Confidential – © 2019 Oracle Internal/Restricted/Highly Restricted Car Data Facts • What are the risks of allowing direct access to car data? • How do vehicle makers and third party providers protect my personal data and privacy? • Why share car data? • What is the safest and most secure way to share car data? • Will vehicle data be available to all service providers and under the same conditions? • What kind of data can my car share? 5 Confidential – © 2019 Oracle Internal/Restricted/Highly Restricted Car Data • Diverse data types • Speed, Engine RPM, Throttle, Load, Pressure, Gear, Braking, Torque, Steer, Wheels rotations and many more (eg. -

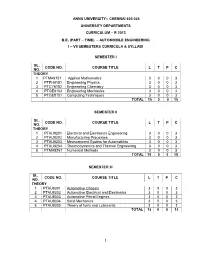

Anna University:: Chennai 600 025 University Departments Curriculum – R 2013 B.E. (Part – Time) – Automobile Engineering

ANNA UNIVERSITY:: CHENNAI 600 025 UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS CURRICULUM – R 2013 B.E. (PART – TIME) – AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING I – VII SEMESTERS CURRICULA & SYLLABI SEMESTER I SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTMA8151 Applied Mathematics 3 0 0 3 2 PTPH8151 Engineering Physics 3 0 0 3 3 PTCY8152 Engineering Chemistry 3 0 0 3 4 PTGE8153 Engineering Mechanics 3 0 0 3 5 PTGE8151 Computing Techniques 3 0 0 3 TOTAL 15 0 0 15 SEMESTER II SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTAU8201 Electrical and Electronics Engineering 3 0 0 3 2 PTAU8202 Manufacturing Processes 3 0 0 3 3 PTAU8203 Measurement System for Automobiles 3 0 0 3 4 PTAU8204 Thermodynamics and Thermal Engineering 3 0 0 3 5 PTMA8251 Numerical Methods 3 0 0 3 TOTAL 15 0 0 15 SEMESTER III SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTAU8301 Automotive Chassis 3 0 0 3 2 PTAU8302 Automotive Electrical and Electronics 3 0 0 3 3 PTAU8303 Automotive Petrol Engines 3 0 0 3 4 PTAU8304 Solid Mechanics 3 0 0 3 5 PTAU8305 Theory of fuels and Lubricants 3 0 0 3 TOTAL 15 0 0 15 1 SEMESTER IV SL. CODE NO. COURSE TITLE L T P C NO. THEORY 1 PTAU8401 Automotive Diesel Engines 3 0 0 3 2 PTAU8402 Automotive Transmission 3 0 0 3 3 PTAU8403 Two and Three Wheeler Technology 3 0 0 3 4 PTPR8351 Kinematics and Dynamics of Machines 3 0 0 3 PRACTICAL 5 PTAU8411 Automotive Engine and Chassis Components 0 0 3 2 Laboratory TOTAL 12 0 3 14 SEMESTER V SL. -

On Processing Personal Data in the Context of Connected Vehicles and Mobility Related Applications

Guidelines 1/2020 on processing personal data in the context of connected vehicles and mobility related applications Version 1.0 Adopted on 28 January 2020 Adopted - version for public consultation 1 Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Related works ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Applicable law .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 Definitions ................................................................................................................................ 9 1.5 Privacy and data protection risks ........................................................................................... 10 2 GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS..................................................................................................... 12 2.1 Categories of data .................................................................................................................. 12 2.2 Purposes ................................................................................................................................. 14 2.3 Relevance and data minimisation ......................................................................................... -

Connected Car Is Talking

Your connected car is talking. Who’s listening? Moving the data-driven user experience forward with value, security and privacy @YourCar: Feeling extra #chatty today. kpmg.com @YourCar: “Monday. 8:23 a.m. 37 degrees. Pulling out of the driveway with Passenger Alex and heading to the office at 123 Main Street.” © 2016 KPMG LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership and the U.S. member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. The KPMG name and logo are registered trademarks or trademarks of KPMG International. NDPPS 604896 Contents About the authors 1 A message from Gary Silberg 3 Securing the high value of data 5 Big data speaks volumes 8 The risky road ahead 14 A closer look under the hood 19 Cybersecurity in a connected car 22 Reaching your data destination 24 About KPMG 28 © 2016 KPMG LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership and the U.S. member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. The KPMG name and logo are registered trademarks or trademarks of KPMG International. NDPPS 604896 About the authors Gary Silberg is KPMG LLP’s (KPMG) national sector lead partner for the automotive industry. With more than 25 years of business experience, including more than 15 years in the automotive industry, he is a leading voice in the media on global trends in the automotive industry. He advises numerous domestic and multinational companies in areas of strategy, mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, and joint ventures. -

Driving Security Into Connected Cars: Threat Model and Recommendations

Driving Security Into Connected Cars: Threat Model and Recommendations Numaan Huq, Craig Gibson, Rainer Vosseler TREND MICRO LEGAL DISCLAIMER The information provided herein is for general information Contents and educational purposes only. It is not intended and should not be construed to constitute legal advice. The information contained herein may not be applicable to all situations and may not reflect the most current situation. Nothing contained herein should be relied on or acted 4 upon without the benefit of legal advice based on the particular facts and circumstances presented and nothing herein should be construed otherwise. Trend Micro The Concept of Connected Cars reserves the right to modify the contents of this document at any time without prior notice. Translations of any material into other languages are intended solely as a convenience. Translation accuracy is not guaranteed nor implied. If any questions arise related to the accuracy of a translation, please refer to 10 the original language official version of the document. Any discrepancies or differences created in the translation are Research on Remote Vehicle Attacks not binding and have no legal effect for compliance or enforcement purposes. Although Trend Micro uses reasonable efforts to include accurate and up-to-date information herein, Trend Micro makes no warranties or representations of any kind as to its accuracy, currency, or completeness. You agree 20 that access to and use of and reliance on this document and the content thereof is at your own risk. Trend Micro Threat Model for Connected Cars disclaims all warranties of any kind, express or implied. Neither Trend Micro nor any party involved in creating, producing, or delivering this document shall be liable for any consequence, loss, or damage, including direct, indirect, special, consequential, loss of business profits, or special damages, whatsoever arising out of access to, 26 use of, or inability to use, or in connection with the use of this document, or any errors or omissions in the content thereof. -

Monetizing Car Data New Service Business Opportunities to Create New Customer Benefits

Monetizing car data New service business opportunities to create new customer benefits Advanced Industries September 2016 Foreword As privately owned vehicles become increasingly connected to each other and to external infrastructures via a growing number of sensors, a massive amount of data is being gener- ated. Gathering this data has become par for the course; leveraging insights from data in ways that can monetize it, however, is still in its nascent stages. To answer key questions around car data monetization and to understand how players along the connected car value chain might capture this potential, McKinsey & Company launched a large-scale, multimodality knowledge initiative course of research: Roundtable sessions conducted in Germany and the USA convened leaders from the automotive (OEMs, suppliers, sales), high-tech, insurance, telecommunications, and finance sectors. Surveys administered in China, Germany, and the USA assessed the preferences, trends, and concerns of about 3,000 customers regarding car data. One-on-one interviews explored the perspectives of car data leaders on the trends and monetization matters in the space. “Customer clinics” collected user observations around preferences and attitudes towards the practicality of various car connectivity features and services. A model was developed to quantify the overall revenue pool related to car data and the opportunity for key industry players based on selected, prioritized use cases. In the following you will find a synthesis of the key findings of this broad, ongoing knowl- edge effort. We would like to thank the many organizations that participated in this exploration of the potential and requirements of car data monetization and that through their contributions made this effort possible. -

The Impact of Automated Transport on the Role, Operations and Costs of Road Operators and Authorities in Finland

The impact of automated transport on the role, operations and costs of road operators and authorities in Finland EU-EIP Activity 4.2 Facilitating automated driving Risto Kulmala, Juhani Jääskeläinen, Seppo Pakarinen Traficomin tutkimuksia ja selvityksiä Traficoms forskningsrapporter och utredningar Traficom Research Reports 6/2019 Traficom Research Reports 6/2019 Julkaisun päivämäärä 12.3.2019 Julkaisun nimi The impact of automated transport on the role, operations and costs of road operators and authorities in Finland (Automaattiajoneuvojen vaikutukset tienpitäjien ja viranomaisten rooliin, toimintaan ja kustannuksiin Suomessa) Tekijät Risto Kulmala, Juhani Jääskeläinen, Seppo Pakarinen Toimeksiantaja ja asettamispäivämäärä Liikennevirasto ja Trafi 22.3.2018 Julkaisusarjan nimi ja numero ISSN verkkojulkaisu) 2342-0294 Traficomin tutkimuksia ja selvityksiä ISBN (verkkojulkaisu) 978-952-311-306-0 6/2019 Asiasanat Automaattiajaminen, tieliikenne, automaattiauto, vaikutus, tienpitäjä. viranomainen, rooli, kustannukset, toiminta, Suomi Tiivistelmä Tämä kansallinen tutkimus tehtiin osana työpakettia ”Facilitating automated driving” EU:n CEF- ohjelman hankkeessa EU EIP keskittyen viiteen korkean tason automaattiajamisen sovellukseen: moottoritieautopilotti, automaattikuorma-autot niille osoitetuilla väylillä, automaattibussit sekaliikenteessä, robottitaksit sekä automaattiset kunnossapito- ja tietyöajoneuvot. Raportti kuvaa automaattiajamiseen liittyvät säädöspuitteet ja viranomaisstrategiat eri puolilla maailmaa ja etenkin Euroopassa. Tutkimus -

Volume 4, 2014, NEIA Connections

Volume 4, 2014 IACP’S ANNUAL CONFERENCE IN THIS ISSUE: OCTOBER 23 – 27 - ORLANDO FLORIDA IACP Conference 1 As is our traditional custom, the Major Cities Chiefs/FBI NEIA Board Meeting Save the Date 2 were held during the IACP conference. A number of the chiefs, graduates Members 3 of the NEI, provided great benefit to their colleagues in attendance. Salt National News 8 Lake City Chief Chris Burbank spoke on “First Net;” Bill Blair, Toronto’s top Chief addressed the serious issue involving police encounters with International News 17 mentally disabled individuals; Baltimore Country’s Chief Johnson on his The Future 21 agency’s Partnership to Prevent Gun Violence; and Chief David Brown Points to Ponder 23 on Dallas’ Ebola Preparations. Typical of such presentations, were the presence of non-law enforcement experts providing added value to the Humor 24 issues under discussion. On the second day, Director Toney Armstrong Contact Information 26 provided information on how his department in Memphis handled what was called the “Memphis Blue Flu.” The issues involving Marijuana Legalization Conference Dates 26 in Colorado and the state of Washington were handled by Chiefs Robert Sponsors 27 White and Kathleen O’Toole. They were followed by an Overall Legislation Committee report provided by Chief Tom Manger, Montgomery County, MD. A little later, a program under consideration with the LAPD called Ceasefire – Cure Violence was presented by Chief Charlie Beck and accompanied by a medical presenter. I would be remiss if I were to ignore the contributions of other law enforcement personnel that represented Philadelphia, Washington DC, Las Vegas, Missouri, Austin TX, and the US Attorney Office. -

Guide to Driving Alternative Fuel Vehicles

Getting the most out of Alternative Fuel Vehicles A guide for driving AFVs Getting the most out of Alternative Fuel Vehicles Evaluating the suitability of an alternative fuel vehicle and placing an order for one are just the beginning of the process of familiarisation. Once the vehicle is delivered, the driver can begin to appreciate how the driving experience differs to that of a conventional car. While those new to AFVs will need to adapt their driving style to get the best out of their new vehicle, they’re also likely to have some new technology to get to grips with. Some of this technology is only found on vehicles with some form of electrification, but other new features are shared across modern petrol and diesel models too. We’ll look first at how operating an AFV can differ to driving a conventional vehicle and then look at some of the emerging technologies. 2 Operating an AFV Getting the most out of an AFV is likely to take a little practice, but there are some relatively simple rules that will help any driver to get started. While these rules will make the biggest difference to drivers of pure electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, they will also help any hybrid driver maximise fuel efficiency and enhance enjoyment of their car. Watch for the torque Unlike ICE powered vehicles, electric cars and hybrids can access the full twist action of their electric motors from a standstill - this means very rapid acceleration from junctions and traffic lights. While this can be very handy in the cut and thrust of urban driving, it can take the unwary by surprise if they are not used to it. -

Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles for Everyday Commute

U.S. Department of Transportation NOFO # 693JJ319NF00001 Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles For Everyday Commute Submitted by: University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA Albemarle County, VA JAUNT Inc. Sonny Merryman, Inc. Charlottesville/Albemarle, VA Evington, VA Perrone Robotics, Inc. ARBOC Specialty Vehicles Crozet, VA Middlebury, IN Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles For Everyday Commute – Project Narrative and Technical Approach University_of_Virginia_Part1 U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington DC 20590 Attn: Sarah Tarpgaard, HCFA-32 Dear Ms. Tarpgaard: We are excited to respond to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Automated Driving System Demonstration Grant (NOFO Number 693JJ319NF00001) with our enclosed proposal entitled: SAVvy Mobility - Demonstrating Safe Autonomous Vehicles For Everyday Commute submitted by the University of Virginia in collaboration with JAUNT Inc, Perrone Robotics Inc., Albemarle County, VA, Sonny Merryman, and ARBOC. We are requesting a total budget of $10M for a demonstration period of 24 months (Sep 2019-Aug 2021). Automated vehicles are rapidly becoming significant components of our nation’s critical infrastructure. While they hold promise for considerable benefits, they also bring with them urgent safety-critical challenges that must be addressed. In addition, as journeys become fully automated, the experience itself will need to become more accessible to all in our population. The safety, mobility, and economic benefits of highly automated vehicles should be accessible to everyone, and everywhere. The majority of automated driving demonstrations to date have focused on operation and impact in urban settings, with the testing of automated cab services. The perspective of the proposed demonstration is much broader: Automated transit vehicles could be the key to catalyzing the mobility for people living in small and medium sized suburban areas. -

Can Next-Generation Vehicles Sustainably Survive in the Automobile Market? Evidence from Ex-Ante Market Simulation and Segmentation

sustainability Article Can Next-Generation Vehicles Sustainably Survive in the Automobile Market? Evidence from Ex-Ante Market Simulation and Segmentation Jungwoo Shin 1, Taehoon Lim 2, Moo Yeon Kim 2 and Jae Young Choi 3,* ID 1 Department of Industrial and Management Systems Engineering, Kyung Hee University, 1732 Deogyeong-daero, Giheung-gu, Yongin, Gyeonggi 17104, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, 301 East Dean Keeton Street, C1700, Austin, TX 78712, USA; [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (M.Y.K.) 3 Graduate School of Technology & Innovation Management, Hanyang University, 222 Wangsimni-ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul 04763, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-2220-2413 Received: 8 January 2018; Accepted: 24 February 2018; Published: 27 February 2018 Abstract: Introduced autonomous and connected vehicles equipped with emerging technologies are expected to change the automotive market. In this study, using stated preference (SP) data collected from choice experiments conducted in Korea with a mixed multiple discrete-continuous extreme value model (MDCEV), we analyzed how the advent of next-generation of vehicles with advanced vehicle technologies would affect consumer vehicle choices and usage patterns. Additionally, ex-ante market simulations and market segmentation analyses were conducted to provide specific management strategies for next-generation vehicles. The results showed that consumer preference structures of conventional and alternative fuel types primarily differed depending on whether they were drivers or non-drivers. Additionally, although the introduction of electric vehicles to the automobile market is expected to negatively affect the choice probability and mileage of other vehicles, it could have a positive influence on the probability of purchasing an existing conventional vehicle if advanced vehicle technologies are available.