Spring 2016 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Medicinal Leaves and Herbs

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY—BULLETIN NO. 219. B. T. GALLOWAY, Chief of Bureau. AMERICAN MEDICINAL LEAVES AND HERBS. ALICE HENKEL, ant, Drug-Plant Investigations. Issued December 8, 191L WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1911. CONTENTS. Page. Introduction 7 Collection of leaves and herbs 7 Plants furnishing medicinal leaves and herbs 8 Sweet fern ( Comptonia peregrina) 9 Liverleaf (Hepatica hepatica and H. acuta) 10 Celandine ( Chelidonium majus) 11 Witch-hazel (Eamamelis virginiana) 12 13 American senna ( Cassia marilandica) Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) 14 Yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum) 15 Pipsissewa ( Chimaphila umbellata) 16 Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) 17 Gravel plant (Epigaea repens) 18 Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) 19 Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) 20 Buckbean ( Menyanthes trifoliata) 21 Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora) 22 Horehound ( Marrubium vu Igare) 23 Catnip (Nepeta cataria) 24 Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) 25 Pennyroyal (Hedeoma pulegioides) 26 Bugleweed (Lycopus virginicus) 27 Peppermint ( Mentha piperita) 28 Spearmint ( Mentha spicata) 29 Jimson weed (Datura stramonium) 30 Balmony (Chelone glabra) 31 Common speedwell ( Veronica officinalis) 32 Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) 32 Squaw vine ( Mitchella repens) 34 Lobelia (Lobelia inflata) 35 Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) 36 Gum plant (Grindelia robusta and G. squarrosa) 37 Canada fleabane (Leptilon canadense) 38 Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) 39 Tansy ( Tanacetum vulgare) 40 Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) 41 Coltsfoot ( Tussilago farfara) 42 Fireweed (Erechthites hieracifolia) 43 Blessed thistle ( Cnicus benedictus) 44 Index 45 219 5 ,. LLUSTRATIONS Page. Fig. 1. Sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina), leaves, male and female catkins 9 2. Liverleaf (Hepatica hepatica), flowering plant. 10 3. -

Eriodictyon Trichocalyx A

I. SPECIES Eriodictyon trichocalyx A. Heller NRCS CODE: Family: Boraginaceae ERTR7 (formerly placed in Hydrophyllaceae) Order: Solanales Subclass: Asteridae Class: Magnoliopsida juvenile plant, August 2010 A. Montalvo , 2010, San Bernardino Co. E. t. var. trichocalyx A. Subspecific taxa ERTRT4 1. E. trichocalyx var. trichocalyx ERTRL2 2. E. trichocalyx var. lanatum (Brand) Jeps. B. Synonyms 1. E. angustifolium var. pubens Gray; E. californicum var. pubens Brand (Abrams & Smiley 1915) 2. E. lanatum (Brand) Abrams; E. trichocalyx A. Heller ssp. lanatum (Brand) Munz; E. californicum. Greene var. lanatum Brand; E. californicum subsp. australe var. lanatum Brand (Abrams & Smiley 1915) C.Common name 1. hairy yerba santa (Roberts et al. 2004; USDA Plants; Jepson eFlora 2015); shiny-leaf yerba santa (Rebman & Simpson 2006); 2. San Diego yerba santa (McMinn 1939, Jepson eFlora 2015); hairy yerba santa (Rebman & Simpson 2006) D.Taxonomic relationships Plants are in the subfamily Hydrophylloideae of the Boraginaceae along with the genera Phacelia, Hydrophyllum, Nemophila, Nama, Emmenanthe, and Eucrypta, all of which are herbaceous and occur in the western US and California. The genus Nama has been identified as a close relative to Eriodictyon (Ferguson 1999). Eriodictyon, Nama, and Turricula, have recently been placed in the new family Namaceae (Luebert et al. 2016). E.Related taxa in region Hannan (2013) recognizes 10 species of Eriodictyon in California, six of which have subspecific taxa. All but two taxa have occurrences in southern California. Of the southern California taxa, the most closely related taxon based on DNA sequence data is E. crassifolium (Ferguson 1999). There are no morphologically similar species that overlap in distribution with E. -

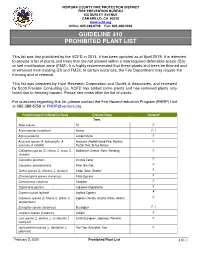

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Investigating the Association of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi with Selected Ornamental Plants Collected from District Charsadda, KPK, Pakistan

Science, Technology and Development 35 (3): 141-147, 2016 ISSN 0254-6418 / DOI: 10.3923/std.2016.141.147 © 2016 Pakistan Council for Science and Technology Investigating the Association of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi with Selected Ornamental Plants Collected from District Charsadda, KPK, Pakistan 1Tabassum Yaseen, 1Ayesha Naseer and 2Muhammad Shakeel 1Department of Botany, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, Pakistan 2Department of Biotechnology, Bacha Khan University Charssada, Pakistan Abstract: This study investigates Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) spore population and root colonization in 25 different ornamental families (35 species) collected from District Charsadda, at early winter and summer seasons. The spore density of AMF ranged from 23-80% and root colonization from 0-100%. The lowest spore density was recorded in Canna indica purpurea, Eriodictyon californicum, Lagerstroemia indica and the highest spore density was recorded in Jasminum sambc. The AMF root colonization was observed to be the lowest in Portulaca indica, Dracaena (Dragon tree) and the highest in Alocasia indica, Chlorophytum borivilianum, Eriodictyon californicum, Cesturnum nocturnum, Euphorbia milli. The present study also reports that roots of a few species of family Portulaceae have not been colonized by AMF. The spore density of AMF and root colonization by these fungi varied from species to species, season to season and also affected by host plant growth stages (vegetative-fruiting). Key words: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, root infection, spores density, ornamental plants, district charsadda INTRODUCTION and drought tolerances (Evelin et al., 2009; Tonin et al., 2001). Among the ornamental plants, Petunia Ornamental plants are plants that are normally grown (Petunia hybrida) is very common and widespread in for ornamental purpose and not expected to be used for Riyadh, as it can be grown under reduced irrigation their nutritional value. -

Sierra Azul Wildflower Guide

WILDFLOWER SURVEY 100 most common species 1 2/25/2020 COMMON WILDFLOWER GUIDE 2019 This common wildflower guide is for use during the annual wildflower survey at Sierra Azul Preserve. Featured are the 100 most common species seen during the wildflower surveys and only includes flowering species. Commonness is based on previous surveys during April for species seen every year and at most areas around Sierra Azul OSP. The guide is a simple color photograph guide with two selected features showcasing the species—usually flower and whole plant or leaf. The plants in this guide are listed by Color. Information provided includes the Latin name, common name, family, and Habit, CNPS Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants rank or CAL-IPC invasive species rating. Latin names are current with the Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, 2012. This guide was compiled by Cleopatra Tuday for Midpen. Images are used under creative commons licenses or used with permission from the photographer. All image rights belong to respective owners. Taking Good Photos for ID: How to use this guide: Take pictures of: Flower top and side; Leaves top and bottom; Stem or branches; Whole plant. llama squash Cucurbitus llamadensis LLAMADACEAE Latin name 4.2 Shrub Common name CNPS rare plant rank or native status Family name Typical bisexual flower stigma pistil style stamen anther Leaf placement filament petal (corolla) sepal (calyx) alternate opposite whorled pedicel receptacle Monocots radial symmetry Parts in 3’s, parallel veins Typical composite flower of the Liliy, orchid, iris, grass Asteraceae (sunflower) family 3 ray flowers disk flowers Dicots Parts in 4’s or 5’s, lattice veins 4 Sunflowers, primrose, pea, mustard, mint, violets phyllaries bilateral symmetry peduncle © 2017 Cleopatra Tuday 2 2/25/2020 BLUE/PURPLE ©2013 Jeb Bjerke ©2013 Keir Morse ©2014 Philip Bouchard ©2010 Scott Loarie Jim brush Ceanothus oliganthus Blue blossom Ceanothus thyrsiflorus RHAMNACEAE Shrub RHAMNACEAE Shrub ©2003 Barry Breckling © 2009 Keir Morse Many-stemmed gilia Gilia achilleifolia ssp. -

Northern Coastal Scrub and Coastal Prairie

GRBQ203-2845G-C07[180-207].qxd 12/02/2007 05:01 PM Page 180 Techbooks[PPG-Quark] SEVEN Northern Coastal Scrub and Coastal Prairie LAWRENCE D. FORD AND GREY F. HAYES INTRODUCTION prairies, as shrubs invade grasslands in the absence of graz- ing and fire. Because of the rarity of these habitats, we are NORTHERN COASTAL SCRUB seeing increasing recognition and regulation of them and of Classification and Locations the numerous sensitive species reliant on their resources. Northern Coastal Bluff Scrub In this chapter, we describe historic and current views on California Sagebrush Scrub habitat classification and ecological dynamics of these ecosys- Coyote Brush Scrub tems. As California’s vegetation ecologists shift to a more Other Scrub Types quantitative system of nomenclature, we suggest how the Composition many different associations of dominant species that make up Landscape Dynamics each of these systems relate to older classifications. We also Paleohistoric and Historic Landscapes propose a geographical distribution of northern coastal scrub Modern Landscapes and coastal prairie, and present information about their pale- Fire Ecology ohistoric origins and landscapes. A central concern for describ- Grazers ing and understanding these ecosystems is to inform better Succession stewardship and conservation. And so, we offer some conclu- sions about the current priorities for conservation, informa- COASTAL PRAIRIE tion about restoration, and suggestions for future research. Classification and Locations California Annual Grassland Northern Coastal Scrub California Oatgrass Moist Native Perennial Grassland Classification and Locations Endemics, Near-Endemics, and Species of Concern Conservation and Restoration Issues Among the many California shrub vegetation types, “coastal scrub” is appreciated for its delightful fragrances AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH and intricate blooms that characterize the coastal experi- ence. -

Bibliographies on Coastal Sage Scrub and Related Malacophyllous Shrublands of Other Mediterranean- California Wildlife Type Climates Conservation Bulletin No

Bibliographies on Coastal Sage Scrub and Related Malacophyllous Shrublands of Other Mediterranean- California Wildlife Type Climates Conservation Bulletin No. 10 1994 Table of Contents: John F. O'Leary Department of Geography San Diego State Preface University San Diego, CA 92182- 1. Animals 4493 2. Autecology 3. Biogeography, Evolution, and Systematics Sandra A. DeSimone Department of Biology 4. Community Composition, Distribution, and San Diego State Classification University 5. Comparisons with Other Malacophyllous San Diego, CA 92182- Shrublands in Mediterranean Climates 0057 6. Conservation, Restoration, and Management 7. Fire, Diversity, and Succession Dennis D. Murphy Center for Conservation 8. Maps Biology 9. Mediterranean Systems (Malacophyllous Only) of Department of Other Regions Biological Sciences 10. Morphology, Phenology, and Physiology Stanford University 11. Mosaics: Coastal Sage Scrub/Chaparral or Stanford CA 94305 Grasslands Peter Brussard 12. Productivity and Nutrient Use Department of Biology 13. Soils and Water Resources University of Nevada Reno, NV 89557-0015 Michael S. Gilpin Department of Biology University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA 92093 Reed F. Noss 7310 N.W. Acorn Ridge Drive Corvallis, OR 97330 Bibliography on Coastal Sage Scrub Shrublands Page 1 of 2 Preface Coastal sage scrub is often referred to as "soft chaparral" to differentiate it from "hard chaparral," the more widespread shrub community that generally occupies more mesic sites and higher elevations in cismontane California. Unlike evergreen, sclerophyllous chaparral, coastal sage scrub is characterized by malacophyllous subshrubs with leaves that abscise during summer drought and are replaced by fewer smaller leaves (Westman 1981, Gray and Schlesinger 1983). Sage scrub also contrasts with chaparral in its lower stature (0.5 - 1.5 meters vs. -

Eriodictyon Crassifolium Benth. NRCS CODE: Family: Boraginaceae (ERCR2) (Formerly Placed in Hydrophyllaceae) Order: Solanales E

I. SPECIES Eriodictyon crassifolium Benth. NRCS CODE: Family: Boraginaceae (ERCR2) (formerly placed in Hydrophyllaceae) Order: Solanales E. c. var. nigrescens, Subclass: Asteridae Zoya Akulova, Creative Commons cc, cultivated at E. c. var. crassifolium, Class: Magnoliopsida Tilden Park, Berkeley W. Riverside Co., E. c. var. crassifolium, W. Riverside Co., A. Montalvo A. Subspecific taxa 1. ERCRC 1. E. crassifolium var. crassifolium 2. ERCRN 2. E. crassifolium var. nigrescens Brand. B. Synonyms 1. Eriodictyon tomentosum of various authors, not Benth.; E. c. subsp. grayanum Brand, in ENGLER, Pflanzenreich 59: I39. I9I3; E. c. var. typica Brand (Abrams & Smiley 1915). 2. Eriodictyon crassifolium Benth. var. denudatum Abrams C.Common name 1. thickleaf yerba santa (also: thick-leaved yerba santa, felt-leaved yerba santa, and variations) (Painter 2016a). 2. bicolored yerba santa (also: thickleaf yerba santa) (Calflora 2016, Painter 2016b). D.Taxonomic relationships Plants are in the subfamily Hydrophylloideae of the Boraginaceae along with the genera Phacelia, Hydrophyllum , Nemophila, Nama, Emmenanthe , and Eucrypta, all of which are herbaceous and occur in the western US and California. The genus Nama has been identified as a close relative to Eriodictyon (Ferguson 1999). Eriodictyon, Nama, and Turricula , have recently been placed in the new family Namaceae (Luebert et al. 2016). E.Related taxa in region Hannan (2016) recognizes 10 species of Eriodictyon in California, six of which have subspecific taxa. All but two taxa have occurrences in southern California. Of the southern California taxa, the most similar taxon is E. trichocalyx var. lanatum, but it has narrow, lanceolate leaves with long wavy hairs; the hairs are sparser on the adaxial (upper) leaf surface than on either variety of E. -

California Sagebrush (Artemisia Californica) Plant Guide

Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Guide CALIFORNIA SAGEBRUSH Artemisia californica Less. Plant Symbol = ARCA11 Common Names: Coastal sagebrush, Coast sagebrush, California sagewort. Scientific Names (The Plant List, 2013; USDA-NRCS, 2020): Artemisia californica var. californica Less. (2011); Artemisia californica var. insularis (Rydb,) Munz (1935). Figure 1 California Sagebrush. James L. Reveal, USDA- NRCS PLANTS Database Description General: Aster Family (Asteraceae). California sagebrush is an aromatic, native, perennial shrub that can reach 5 to 8 feet in height. It has a generally rounded growth habit, with slender, flexible stems branching from the base of the plant. Leaves are more or less hairy, light green to gray in color, usually 0.8 to 4.0 inches in length, with 2 to 4 thread-like lobes that are less than 0.04 inches wide, with the margins curled under. California sagebrush blooms in the later summer to autumn/winter (depending on locale), and inflorescences are long, narrow, leafy and sparse, generally exceeding the leaves, with heads less than 0.2 inches in diameter that nod when in fruit (Hickman, 1993). Distribution: California sagebrush is found in coastal sage scrub communities from southwestern coastal Oregon, along the California coast and foothills, south into northern Baja California, Mexico (Figure 2) (Hickman, 1993). It also occurs on the coastal islands of California and Baja, generally below 3300 feet elevation, but may extend inland (and over 4920 feet in elevation) from the coastal zone. Habitat Adaptation This shrub is a dominant component of the coastal sage scrub, and an important member of some chaparral, coastal dune and dry foothill plant communities, especially near the coast (Hickman, 1993). -

Uc Santa Cruz Recommended Native Plants, Non-Native Plants, and Grass

CAMPUS STANDARDS APPENDIX A UC SANTA CRUZ RECOMMENDED NATIVE PLANTS, NON-NATIVE PLANTS, AND GRASS SEED MIXTURES May 1, 1998 5/1/98 UCSC Campus Standards Handbook Plant List Appendix A 1 * May not be appropriate in some campus locations due to messiness or susceptibility to fungus, frost, deer, pests, etc. REDWOOD FORESTS Predominant native species at UCSC with commercial availability Scientific Name Common Name TREES: Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple Sequoia sempervirens Coast Redwood SHRUBS: Corylus cornuta var. californica Western Hazelnut Rosa gymnocarpa Wood Rose Ribes sanguineum var. glutinosum Red Flowering Currant Vaccinium ovatum California Huckleberry GROUND COVER: Oxalis oregana Redwood Sorrell Petasites frigidus var. palmatus Coltsfoot * Polystichum munitum Sword Fern Symphoricarpos mollis Creeeping Snowberry Trillium ovatum Wake Robin Whipplea modesta Yerba De Selva Viola sempervirons Evergreen Violet WET HABITAT GROUNDCOVER: Athyrium filix-femina Lady Fern Equisetum spp. Horse Tail Ranuculus californicus Buttercup Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern NATIVE PLANTS ASSOCIATED WITH REDWOOD FORESTS Not necessarily predominant species at UCSC Scientific Name Common Name TREES: Acer macrophyllum Big Leaf Maple Quercus agrifolia Coast Live Oak Torreya californica California Nutmeg Cornus nuttallii Western Dogwood September 2016 UCSC Campus Standards Handbook Plant List Appendix A 2 Quercus chrysolepis Canyon Live Oak Quercus kelloggi California Black Oak Quercus wislizenii Interior Live Oak SHRUBS: Acer circinatum Vine Maple Berberis -

The Ethnobotany of the Yurok, Tolowa, and Karok Indians of Northwest California

THE ETHNOBOTANY OF THE YUROK, TOLOWA, AND KAROK INDIANS OF NORTHWEST CALIFORNIA by Marc Andre Baker 'A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts June, 1981 THE ETHNOBOTANY OF THE YUROK, TOLOWA, AND KAROK INDIANS OF NORTHWEST CALIFORNIA by Marc A. Baker Approved by the Master's Thesis Corrunittee V~+J~.Jr, Chairman ~;'J.~''c \. (l .:, r---- (I'. J~!-\ Approved by the Graduate Dean ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS An ethnobotanical study necessitates the cooperation of individuals who among themselves have a wide range of diverse interests. Dr. James Payne Smith, Jr., Professor of Botany was the chief coordinator of this unity as well as my princi- pal advisor and editor. Most of the botanical related prob- lems and many grammatical questions were discussed with him. Torn Nelson, Herbarium Assistant of the HSU Herbarium, aided in the identification of many plant specimens. Dr. Jim Waters, Professor of Zoology, dealt with cor- rections concerning his field, and discerningly and meticu- lously proofread the entire text. From the formal field of ethnology, Dr. Pat Wenger, Professor of Anthropolo~y, worked with me on problems in linguistics, phonetics, and other aspects of ethnography. He also discussed with me many definitions, theories, and atti- tudes of modern ethnologists. The field work would not have been possible without the help of Torn Parsons, Director of the Center for Community Development, Arcata, California. Mr. Parsons has been work- ing with the Tolowa, Karok, and Yurok for many years and was able to introduce me to reliable and authentic sources of cultural information. -

Alluvial Scrub Vegetation of Southern California, a Focus on the Santa Ana River Watershed in Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties, California

Alluvial Scrub Vegetation of Southern California, A Focus on the Santa Ana River Watershed In Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties, California By Jennifer Buck-Diaz and Julie M. Evens California Native Plant Society, Vegetation Program 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 In cooperation with Arlee Montalvo Riverside-Corona Resource Conservation District (RCRCD) 4500 Glenwood Drive, Bldg. A Riverside, CA 92501 September 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Background and Standards .......................................................................................................... 1 Table 1. Classification of Vegetation: Example Hierarchy .................................................... 2 Methods ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Study Area ................................................................................................................................3 Field Sampling ..........................................................................................................................3 Figure 1. Study area map illustrating new alluvial scrub surveys.......................................... 4 Figure 2. Study area map of both new and compiled alluvial scrub surveys. ....................... 5 Table 2. Environmental Variables ........................................................................................