The Ethnobotany of the Yurok, Tolowa, and Karok Indians of Northwest California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail

*Non-native Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail Plant List as of 7/12/2016 compiled by Tanya Harvey T24S.R3E.S33;T25S.R3E.S4 westerncascades.com FERNS & ALLIES Pseudotsuga menziesii Ribes lacustre Athyriaceae Tsuga heterophylla Ribes sanguineum Athyrium filix-femina Tsuga mertensiana Ribes viscosissimum Cystopteridaceae Taxaceae Rhamnaceae Cystopteris fragilis Taxus brevifolia Ceanothus velutinus Dennstaedtiaceae TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Rosaceae Pteridium aquilinum Adoxaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Dryopteridaceae Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea Holodiscus discolor Polystichum imbricans (Sambucus mexicana, S. cerulea) Prunus emarginata (Polystichum munitum var. imbricans) Sambucus racemosa Rosa gymnocarpa Polystichum lonchitis Berberidaceae Rubus lasiococcus Polystichum munitum Berberis aquifolium (Mahonia aquifolium) Rubus leucodermis Equisetaceae Berberis nervosa Rubus nivalis Equisetum arvense (Mahonia nervosa) Rubus parviflorus Ophioglossaceae Betulaceae Botrychium simplex Rubus ursinus Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata Sceptridium multifidum (Alnus sinuata) Sorbus scopulina (Botrychium multifidum) Caprifoliaceae Spiraea douglasii Polypodiaceae Lonicera ciliosa Salicaceae Polypodium hesperium Lonicera conjugialis Populus tremuloides Pteridaceae Symphoricarpos albus Salix geyeriana Aspidotis densa Symphoricarpos mollis Salix scouleriana Cheilanthes gracillima (Symphoricarpos hesperius) Salix sitchensis Cryptogramma acrostichoides Celastraceae Salix sp. (Cryptogramma crispa) Paxistima myrsinites Sapindaceae Selaginellaceae (Pachystima myrsinites) -

American Medicinal Leaves and Herbs

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY—BULLETIN NO. 219. B. T. GALLOWAY, Chief of Bureau. AMERICAN MEDICINAL LEAVES AND HERBS. ALICE HENKEL, ant, Drug-Plant Investigations. Issued December 8, 191L WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1911. CONTENTS. Page. Introduction 7 Collection of leaves and herbs 7 Plants furnishing medicinal leaves and herbs 8 Sweet fern ( Comptonia peregrina) 9 Liverleaf (Hepatica hepatica and H. acuta) 10 Celandine ( Chelidonium majus) 11 Witch-hazel (Eamamelis virginiana) 12 13 American senna ( Cassia marilandica) Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) 14 Yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum) 15 Pipsissewa ( Chimaphila umbellata) 16 Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) 17 Gravel plant (Epigaea repens) 18 Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) 19 Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) 20 Buckbean ( Menyanthes trifoliata) 21 Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora) 22 Horehound ( Marrubium vu Igare) 23 Catnip (Nepeta cataria) 24 Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) 25 Pennyroyal (Hedeoma pulegioides) 26 Bugleweed (Lycopus virginicus) 27 Peppermint ( Mentha piperita) 28 Spearmint ( Mentha spicata) 29 Jimson weed (Datura stramonium) 30 Balmony (Chelone glabra) 31 Common speedwell ( Veronica officinalis) 32 Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) 32 Squaw vine ( Mitchella repens) 34 Lobelia (Lobelia inflata) 35 Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) 36 Gum plant (Grindelia robusta and G. squarrosa) 37 Canada fleabane (Leptilon canadense) 38 Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) 39 Tansy ( Tanacetum vulgare) 40 Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) 41 Coltsfoot ( Tussilago farfara) 42 Fireweed (Erechthites hieracifolia) 43 Blessed thistle ( Cnicus benedictus) 44 Index 45 219 5 ,. LLUSTRATIONS Page. Fig. 1. Sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina), leaves, male and female catkins 9 2. Liverleaf (Hepatica hepatica), flowering plant. 10 3. -

Eriodictyon Trichocalyx A

I. SPECIES Eriodictyon trichocalyx A. Heller NRCS CODE: Family: Boraginaceae ERTR7 (formerly placed in Hydrophyllaceae) Order: Solanales Subclass: Asteridae Class: Magnoliopsida juvenile plant, August 2010 A. Montalvo , 2010, San Bernardino Co. E. t. var. trichocalyx A. Subspecific taxa ERTRT4 1. E. trichocalyx var. trichocalyx ERTRL2 2. E. trichocalyx var. lanatum (Brand) Jeps. B. Synonyms 1. E. angustifolium var. pubens Gray; E. californicum var. pubens Brand (Abrams & Smiley 1915) 2. E. lanatum (Brand) Abrams; E. trichocalyx A. Heller ssp. lanatum (Brand) Munz; E. californicum. Greene var. lanatum Brand; E. californicum subsp. australe var. lanatum Brand (Abrams & Smiley 1915) C.Common name 1. hairy yerba santa (Roberts et al. 2004; USDA Plants; Jepson eFlora 2015); shiny-leaf yerba santa (Rebman & Simpson 2006); 2. San Diego yerba santa (McMinn 1939, Jepson eFlora 2015); hairy yerba santa (Rebman & Simpson 2006) D.Taxonomic relationships Plants are in the subfamily Hydrophylloideae of the Boraginaceae along with the genera Phacelia, Hydrophyllum, Nemophila, Nama, Emmenanthe, and Eucrypta, all of which are herbaceous and occur in the western US and California. The genus Nama has been identified as a close relative to Eriodictyon (Ferguson 1999). Eriodictyon, Nama, and Turricula, have recently been placed in the new family Namaceae (Luebert et al. 2016). E.Related taxa in region Hannan (2013) recognizes 10 species of Eriodictyon in California, six of which have subspecific taxa. All but two taxa have occurrences in southern California. Of the southern California taxa, the most closely related taxon based on DNA sequence data is E. crassifolium (Ferguson 1999). There are no morphologically similar species that overlap in distribution with E. -

Exudate Flavonoids of Eight Species of Ceanothus (Rhamnaceae) Eckhard Wollenwebera,*, Marion Dörra, Bruce A

Exudate Flavonoids of Eight Species of Ceanothus (Rhamnaceae) Eckhard Wollenwebera,*, Marion Dörra, Bruce A. Bohmb, and James N. Roitmanc a Institut für Botanik der TU Darmstadt, Schnittspahnstrasse 3, D-64287 Darmstadt, Germany. Fax: 0049-6151/164630. E-mail: [email protected] b Botany Department, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada c Western Regional Research Center, USDA-ARS, 800 Buchanan Street, Albany, CA 94710, U.S.A. * Author for correspondance and reprint requests Z. Naturforsch. 59c, 459Ð462 (2004); received April 26/May 13, 2004 Leaf glands of Ceanothus species excrete a lipophilic material that contains a variety of flavonoids. Most of these are aglycones, but some glycosides were also observed. Seven out of eight species exhibit flavonols, whereas flavones are excreted by only one species. Four species produce flavanones and dihydroflavonols; one excretes a remarkable quantity of fla- vonol glycosides. The exudate flavonoids thus form different patterns that might be charac- teristic for different Ceanothus species. Key words: Ceanothus, Rhamnaceae, Exudates, Flavonoids Introduction The genus Ceanothus (Rhamnaceae) contains about 60 species. These are deciduous or ever- green shrubs or rarely small trees that are some- Many species of the Rhamnaceae genus Ceano- times spiny. They occur chiefly in the Pacific coast thus bear multicellular glandular trichomes on region of North America from southwestern Can- their leaves, in particular along the margins. Fig. 1 ada to northern Mexico. Several species are culti- shows these glands on a leaf of C. papillosus and vated as ornamentals, and are available from local the typical shape of an individual C. hearstiorum nurseries. -

Dog Mountain

Dog Mt. Columbia River Gorge Skamania County, WA T3N R9E S 19, 20, 29, 30, 31, 32 Updated May 5, 2011 Flora Northwest- http://science.halleyhosting.com List compiled after numerous visits by Paul Slichter, from historical records and from NPSO and WNPS lists. Common Name Scientific Name Family Vine Maple Acer circinatum Aceraceae Big-leaf Maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae Poison Oak Toxicodendron diversiloba Anacardiaceae Sharp-tooth Angelica Angelica arguta Apiaceae Bur Chervil Anthriscus caucalis Apiaceae Wild Chervil ? Anthriscus sylvestris ? Apiaceae Queen Anne's Lace Daucus carota Apiaceae Cow Parsnip Heracleum maximum Apiaceae Gray's Lovage Ligusticum grayi Apiaceae Fernleaf Desert Parsley Lomatium dissectum v. dissectum Apiaceae Slender-fruited Desert Parsley? Lomatium leptocarpum ? Apiaceae Martindale's Desert Parsley Lomatium martindalei Apiaceae Bare-stem Desert Parsley Lomatium nudicaule Apiaceae Nine-leaf Desert Parsley Lomatium triternatum (v. anomalum ?) Apiaceae Nine-leaf Desert Parsley Lomatium triternatum v. triternatum Apiaceae Common Sweet Cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae Mountain Sweet Cicely Osmorhiza occidentalis Apiaceae Sierra Snake Root Sanicula graveolens Apiaceae Flytrap Dogbane Apocynum androsaemifolium Apocynaceae Common Periwinkle Vinca minor Apocynaceae Devils Club Oploplanax horridum Araliaceae Wild Ginger Asarum caudatum Aristolochaceae Yarrow Achillea millefolium Asteraceae Pathfinder Adenocaulon bicolor Asteraceae Large-flowered Agoseris ? Agoseris grandiflora Asteraceae Annual Agoseris Agoseris heterophylla -

Buzz-Pollination and Patterns in Sexual Traits in North European Pyrolaceae Author(S): Jette T

Buzz-Pollination and Patterns in Sexual Traits in North European Pyrolaceae Author(s): Jette T. Knudsen and Jens Mogens Olesen Reviewed work(s): Source: American Journal of Botany, Vol. 80, No. 8 (Aug., 1993), pp. 900-913 Published by: Botanical Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2445510 . Accessed: 08/08/2012 10:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Botanical Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Botany. http://www.jstor.org American Journalof Botany 80(8): 900-913. 1993. BUZZ-POLLINATION AND PATTERNS IN SEXUAL TRAITS IN NORTH EUROPEAN PYROLACEAE1 JETTE T. KNUDSEN2 AND JENS MOGENS OLESEN Departmentof ChemicalEcology, University of G6teborg, Reutersgatan2C, S-413 20 G6teborg,Sweden; and Departmentof Ecology and Genetics,University of Aarhus, Ny Munkegade, Building550, DK-8000 Aarhus,Denmark Flowerbiology and pollinationof Moneses uniflora, Orthilia secunda, Pyrola minor, P. rotundifolia,P. chlorantha, and Chimaphilaumbellata are describedand discussedin relationto patternsin sexualtraits and possibleevolution of buzz- pollinationwithin the group. The largenumber of pollengrains are packedinto units of monadsin Orthilia,tetrads in Monesesand Pyrola,or polyadsin Chimaphila.Pollen is thesole rewardto visitinginsects except in thenectar-producing 0. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Antileishmanial Compounds from Nature - Elucidation of the Active Principles of an Extract from Valeriana Wallichii Rhizomes

ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 Eingereicht am ....................................... bei der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie 1. Gutachter Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Gutachter ........................................ der Dissertation 1. Prüfer Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Prüfer ......................................... 3. Prüfer ......................................... des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums Datum des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums .................................................. Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am .................................................. "Wer nichts als Chemie versteht, versteht auch die nicht recht." Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799) DANKSAGUNG Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde am Institut für Pharmazie und Lebensmittelchemie der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg auf Anregung und unter Anleitung von Frau Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe und finanzieller Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 630) angefertigt. Ich -

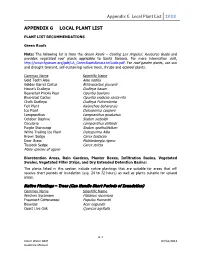

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX G LOCAL PLANT LIST PLANT LIST RECOMMENDATIONS Green Roofs Note: The following list is from the Green Roofs – Cooling Los Angeles: Resource Guide and provides vegetated roof plants applicable to Santa Barbara. For more information visit, http://www.fypower.org/pdf/LA_GreenRoofsResourceGuide.pdf. For roof garden plants, use sun and drought tolerant, self-sustaining native trees, shrubs and ecoroof plants. Common Name Scientific Name Gold Tooth Aloe Aloe nobilis Golden Barrel Cactus Echinocactus grusonii Hasse’s Dudleya Dudleya hassei Beavertail Prickly Pear Opuntia basilaris Blue-blad Cactus Opuntia violacea santa-rita Chalk Dudleya Dudleya Pulverulenta Felt Plant Kalanchoe beharensis Ice Plant Delosperma cooperii Lampranthus Lampranthus productus October Daphne Sedum sieboldii Oscularia Lampranthus deltoids Purple Stonecrop Sedum spathulifolium White Trailing Ice Plant Delosperma Alba Brown Sedge Carex testacea Deer Grass Muhlenbergia rigens Tussock Sedge Carex stricta Many species of agave Bioretention Areas, Rain Gardens, Planter Boxes, Infiltration Basins, Vegetated Swales, Vegetated Filter Strips, and Dry Extended Detention Basins: The plants listed in this section include native plantings that are suitable for areas that will receive short periods of inundation (e.g. 24 to 72 hours) as well as plants suitable for upland areas. Native Plantings – Trees (Can Handle Short Periods of Inundation) Common Name Scientific Name Western Sycamore Platanus racemosa Freemont Cottonwood Populus fremontii -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Vascular Plants of Horse Mountain (Humboldt County, California) James P

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 4-2019 Vascular Plants of Horse Mountain (Humboldt County, California) James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] John O. Sawyer Jr. Humboldt State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr and Sawyer, John O. Jr., "Vascular Plants of Horse Mountain (Humboldt County, California)" (2019). Botanical Studies. 38. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/38 This Flora of Northwest California: Checklists of Local Sites of Botanical Interest is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VASCULAR PLANTS OF HORSE MOUNTAIN (HUMBOLDT COUNTY, CALIFORNIA) Compiled by James P. Smith, Jr. & John O. Sawyer, Jr. Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California Fourth Edition · 29 April 2019 Horse Mountain (elevation 4952 ft.) is located at 40.8743N, -123.7328 W. The Polystichum x scopulinum · Bristle or holly fern closest town is Willow Creek, about 15 miles to the northeast. Access is via County Road 1 (Titlow Hill Road) off State Route 299. You have now left the Coast Range PTERIDACEAE BRAKE FERN FAMILY and entered the Klamath-Siskiyou Region. The area offers commanding views of Adiantum pedatum var. aleuticum · Maidenhair fern the Pacific Ocean and the Trinity Alps.