Download Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Opaque Nature of John Constable's Naturalism

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 12:44 RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review The Opaque Nature of John Constable’s Naturalism Iris Wien The Nature of Naturalism : A Trans-Historical Examination Résumé de l'article La nature du naturalisme : un examen transhistorique Situant les dessins de Constable dans un contexte épistémologique Volume 41, numéro 2, 2016 post-Berkleyien, cet article suggère que le basculement vers une structure représentationnelle, qui met l’accent sur l’écart entre les fonctions figuratives URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1038071ar et picturales, avait été nécessaire pour assurer la prétention à la vérité du DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1038071ar naturalisme de l’artiste. Nous soutenons que les modulations réalistes dans la conceptualisation sémiotique de Berkeley de la perception visuelle furent instrumentales à une esthétique qui s’efforçait d’enligner le langage de la Aller au sommaire du numéro nature avec le sentiment, réconciliant ainsi l’expression subjective et les demandes de l’objectivité. Pourtant, ainsi que nous le démontrons, la rupture d’un ordre de représentation « transparent » qu’opéra Constable eut des Éditeur(s) implications non seulement scientifiques, mais également idéologiques. UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (imprimé) 1918-4778 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Wien, I. (2016). The Opaque Nature of John Constable’s Naturalism. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 41(2), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038071ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain | University of Stirling

10/01/21 HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain | University of Stirling HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: View Online Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain E V Macleod Aspinall, A. (1949) Politics and the press, c.1780-1850. Home and Van Thal. Barker, H. (1996) ‘Catering for Provisional Tastes: Newspapers, Readership and Profit in Late Eighteenth-Century England’, Historical Research, 69(168), pp. 42–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.1996.tb01841.x. Barker, H. (2000) ‘Growth of newspapers, IN: Newspapers, politics and English society 1695-1855’, in Newspapers, politics and English society, 1695-1855. Harlow: Longman, pp. 29–45. Barker, Hannah and Chalus, Elaine (1997) Gender in eighteenth-century England: roles, representations and responsibilities. London: Longman. Bennett, Betty T. (1976) British war poetry in the age of romanticism, 1793-1815. New York: Garland Pub. Bindman, D. (1999) ‘Prints’, in An Oxford companion to the Romantic age: British culture, 1776-1832. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 207–213. Bob Harris (1995) ‘The London Evening Post and Mid-Eighteenth-Century British Politics’, The English Historical Review, 110(439), pp. 1132–1156. Available at: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.stir.ac.uk/stable/577253. Bohstedt, J. (1988) ‘GENDER, HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY POLITICS: WOMEN IN ENGLISH RIOTS 1790–1810’, Past and Present, 120(1), pp. 88–122. doi: 10.1093/past/120.1.88. Booth, A. (1977a) ‘FOOD RIOTS IN THE NORTH–WEST OF ENGLAND 1790–1801’, Past and Present, 77(1), pp. 84–107. doi: 10.1093/past/77.1.84. Booth, A. (1977b) ‘FOOD RIOTS IN THE NORTH–WEST OF ENGLAND 1790–1801’, Past and Present, 77(1), pp. -

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England founded in 1913.) . EDITOR; Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 5 No.8 May 1996 CONTENTS Editorial and Notes .......................................... 438 Gordon Esslemont by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 439 The Origins of the Missionary Society by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D . ........................... 440 Manliness and Mission: Frank Lenwood and the London Missionary Society by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 458 Training for Hoxton and Highbury: Walter Scott of Rothwell and his Pupils by Geoffrey F. Nuttall, F.B.A., M.A., D.D. ................... 477 Mr. Seymour and Dr. Reynolds by Edwin Welch, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. ....................... 483 The Presbyterians in Liverpool. Part 3: A Survey 1900-1918 by Alberta Jean Doodson, M.A., Ph.D . ....................... 489 Review Article: Only Connect by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 495 Review Article: Mission and Ecclesiology? Some Gales of Change by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 499 Short Reviews by Daniel Jenkins and David M. Thompson 503 Some Contemporaries by Alan P.F. Sell, M.A., B.D., Ph.D . ......................... 505 437 438 EDITORIAL There is a story that when Mrs. Walter Peppercorn gave birth to her eldest child her brother expressed the hope that the little peppercorn would never get into a piclde. This so infuriated Mr. Peppercorn that he changed their name to Lenwood: or so his wife's family liked to believe. They were prosperous Sheffielders whom he greatly surprised by leaving a considerable fortune; he had proved to be their equal in business. -

Very Rough Draft

Friends and Colleagues: Intellectual Networking in England 1760-1776 Master‟s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Comparative History Mark Hulliung, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master‟s Degree by Jennifer M. Warburton May 2010 Copyright by Jennifer Warburton May 2010 ABSTRACT Friends and Colleagues: Intellectual Networking in England 1760- 1776 A Thesis Presented to the Comparative History Department Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Jennifer Warburton The study of English intellectualism during the latter half of the Eighteenth Century has been fairly limited. Either historians study individual figures, individual groups or single debates, primarily that following the French Revolution. My paper seeks to find the origins of this French Revolution debate through examining the interactions between individuals and the groups they belonged to in order to transcend the segmentation previous scholarship has imposed. At the center of this study are a series of individuals, most notably Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, Benjamin Franklin, Dr. John Canton, Rev. Theophilus Lindsey and John Jebb, whose friendships and interactions among such diverse disciplines as religion, science and politics characterized the collaborative yet segmented nature of English society, which contrasted so dramatically with the salon culture of their French counterparts. iii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ -

ACTS, 1787-1790 G. M. Ditchfield, B.A., Ph.D

THE CAMPAIGN IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE FOR THE REPEAL OF THE TEST AND CORPORATION ACTS, 1787-1790 G. M. Ditchfield, B.A., Ph.D. N due season we shall reap, if we faint not'. A sermon on this Itext was preached by a Lancashire Dissenting minister on 7 March 1790, five days after the House of Commons had rejected a motion for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts by the decisive margin of 294 votes to IO5-1 The text serves to illustrate the religious nature of the issue in question and the sense of injustice which it aroused. Both points are significant. For many historians of the period seem to agree that a new 'political con sciousness' based on discontented radicalism and on a greatly increased degree of popular participation in political activity appeared in Lancashire and Cheshire in the late 17805 and in the 17905. It is proposed here to suggest at least one reason why this should have been so and to offer a religious dimension to what has been called 'the emergence of liberalism'.2 The continued existence of the Test and Corporation Acts, with their seventeenth century heritage, remained a potential source of conflict between the established church and those outside it. The renewed efforts to secure their repeal in 1787-90, though unsuccessful, helped to concentrate dissatisfaction with the 'old regime', to facilitate the development of the radical consciousness of the early nineteenth century and to promote the clearer identification and organisation of the forces which were opposed to change. This conflict took on a particularly bitter tone in Lancashire and Cheshire. -

The Leicestershire Riots of 1773 and 1787

The Leicester Riots of 1773 and 1787: a study of the victims of popular protest by David L. Wykes In recent years, social historians have paid considerable attention to studies on popular protest. Indeed, the present interest in examining the origins of working-class movements in this country would hardly have been possible without such work. 1 The weight of research, as a result, has rather naturally fallen on studies of popular protest during the first half of the nineteenth century, in particular oh the outstanding disturbances such as the machine breaking outrages of 18'11-16, the Reform Bill riots of 1831 and the Chartist riots of 1839 and 1842. 2 Although much of the work on popular protest has been concerned with this later period, a number of independent studies have been made for the eighteenth century. The work has been mainly on provincial food riots and industrial disorders (generally with reference to London),3 and on radical reform movements and movements directed against radical reformers (especially 'Church and King' riots). 4 Work on popular disturbances in Leicestershire reflects this emphasis, and the main concern has been with Luddites and early trade union activity. 5 Studies on the beginning of trade unionism in Leicester have led to an examination of eighteenth-century riots in the town in the hope of providing some information on early trade combinations and similar activities,6 but there are details of disturbances in the second half of the eighteenth century worth considering in themselves, particularly in the light of more recent studies on crowd behaviour. -

The Right of Resistance in Richard Price and Joseph Priestley Rémy Duthille

The right of resistance in Richard Price and Joseph Priestley Rémy Duthille To cite this version: Rémy Duthille. The right of resistance in Richard Price and Joseph Priestley. History of European Ideas, Elsevier, 2018, pp.1 - 14. 10.1080/01916599.2018.1473957. hal-01845996 HAL Id: hal-01845996 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01845996 Submitted on 20 Jul 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Original Articles The right of resistance in Richard Price and Joseph Priestley Rémy Duthille Published online: 20 Jun 2018 Rémy Duthille (2018) The right of resistance in Richard Price and Joseph Priestley, History of European Ideas, DOI: 10.1080/01916599.2018.1473957 ABSTRACT This article is concerned with the writings on resistance by Richard Price and Joseph Priestley, the leaders of the Rational Dissenters who supported the American and French Revolutions, from the late 1760s to 1791. The article discusses the differences between Rational Dissent and mainstream (Court) Whig resistance theory, as regards history in particular: the Dissenters viewed the Glorious Revolution as a lost opportunity rather than a full triumph and claimed the heritage of the Puritan opposition to Charles I, some of them justifying the regicide. -

(2019) Revolutionary Contexts for the Quest: Jesus in the Rhetoric and Methods of Early Modern Intellectual History

\ Birch, J. C.P. (2019) Revolutionary contexts for the quest: Jesus in the rhetoric and methods of Early Modern intellectual history. Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus, 17(1-2), pp. 35-80. (doi: 10.1163/17455197- 01701005) The material cannot be used for any other purpose without further permission of the publisher and is for private use only. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/187702/ Deposited on 17 September 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk REVOLUTIONARY CONTEXTS FOR THE QUEST Jesus in the Rhetoric and Methods of Early Modern Intellectual History Abstract: This article contributes to a new perspective on the historical Jesus in early modern intellectual history. This perspective looks beyond German and academic scholarship, and takes account of a plurality of religious, social, and political contexts. Having outlined avenues of research which are consistent with this approach, I focus on radicalised socio- political contexts for the emergence of 'history' as a category of analysis for Jesus. Two contexts will be discussed: the late eighteenth century, with reference to Joseph Priestley, Baron d'Holbach, and their associations with the French Revolution; and the interregnum period in seventeenth-century Britain, with reference to early Quaker controversies and the apologetic work of Henry More. I identify ideas about Jesus in those contexts which have echoed in subsequent scholarship, while challenging the notion that there is a compelling association between sympathetic historical conceptions of Jesus (as opposed to theological) and a tendency towards radical and revolutionary politics. -

Riotous Community: Crowds, Politics and Society in Wales, C.1700–1840', Welsh History Review, 20:4 (2001), Pp.656-86

Sharon Howard, 'Riotous community: crowds, politics and society in Wales, c.1700–1840', Welsh History Review, 20:4 (2001), pp.656-86. This is an author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Welsh History Review. It has been peer-reviewed but does not include final copy- editing, proof corrections, published layout or pagination. The publisher's webpage for the journal is at http://www.uwp.co.uk/book_desc/whr.html Any use of this article should comply with copyright law. It may be freely used for personal study and research, provided any use of any part of it in subsequent published or unpublished work is accurately acknowledged. To cite this version: Sharon Howard, 'Riotous community: crowds, politics and society in Wales, c.1700–1840', http://www.earlymodernweb.org.uk/archive/riotous_community.pdf. Electronic versions of some of my other publications can be found at http://www.earlymodernweb.org.uk/emr/index.php/publications-archive/ Early Modern Resources http://www.earlymodernweb.org.uk/ 1 Riotous community: t he crowd, politics and society in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Wales Sharon Howard Department of History and Welsh History University of Wales, Aberystwyth Historians of early modern Wales have, since the Second World War, dramatically expanded our understanding of this period. However, they have tended to concentrate on a limited number of topics: the activities of the ruling classes and, especially in the later part of the period, a variety of ‘awakenings’ – religious, national-cultural, industrial and class-politics. The story of the common people of Wales in the century or more before industrialization has been, in the main, one of lack, hardship and suffering.1 Without doubt, their lives were tremendously precarious, difficult and often short: this is not Merrie Wales. -

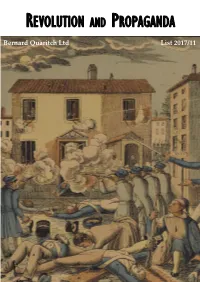

Revolution and Propaganda

REVOLUTION AND PROPAGANDA Bernard Quaritch Ltd List 2017/11 BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 40 SOUTH AUDLEY STREET, LONDON W1K 2PR Tel: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC, 1 Churchill Place, London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-82 Swift code: BARCGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account: IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 VAT number: GB 840 1358 54 Mastercard, Visa, and American Express accepted Recent Catalogues: 1435 Music 1434 Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts 1433 English Books & Manuscripts Recent Lists: 2017/10 Bertrand Russell 2017/9 English Books 1550-1850 2017/8 Medicine, Sexology, Gastronomy no. 6 Cover image taken from no. 37. N.B. Prices marked with an asterisk are subject to VAT within the EU. 1. ALBERTI, Rafael. 13 Bandas y 48 estrellas. Poema del Mar Caribe. Madrid, Manuel Altolaguirre, 1936. Large 8vo, pp. 39, [1]; a very good copy in recent light blue quarter morocco, spine gilt, the original illustrated wrappers bound in, blank leaves bound at end. £650 First edition. ‘The thirteen poems collected in 13 bandas y 48 estrellas, first published in 1936 and later recollected in part 3 of De un momento a otro, are songs of protest against, and critical evaluations of, the role of “el imperialismo yanki”, “la diplomacia del horror”, and “la intervención armada” in the Americas, their effects on the people, and the limitations they place on freedom’ (Judith Nantell, Rafael Alberti’s poetry of the Thirties, University of Georgia Press, 1986, p. -

The Background to the Sacheverel Riots

The Background to the Sacheverell Riots of 1714 and 1715 in Birmingham and the Sutton Coldfield Connection By Roy Billingham Henry Sacheverell, by Thomas Gibson, c.1710 In the autumn of 1714 the townsfolk of Sutton Coldfield were witnesses to an event that occurred at their parish church that was symptomatic of the religious and political passions which were rife at this period both in the Midlands and elsewhere in Britain. Jacobitism was like a smouldering fuse that burnt for many years creating social unrest and threatening mayhem, and Sutton Coldfield played a minor role in this state of affairs in the Midlands. Queen Anne had recently died and the Nation was facing up to the Hanoverian succession that was bitterly opposed by many sections of society who were either in favour of a hereditary royal succession or were against the imposition of a foreign king. However, it perhaps will help our understanding of these turbulent events if we consider the elements of British history that contributed to this situation. Following the controversial ‘warming-pan’ birth of James Francis Edward Stuart in 1688 to Mary of Modena, James II’s second wife and a Catholic whose babies had previously either miscarried or died in infancy, and after receiving a written invitation from four Whig lords and three Tories, the Calvinist William III of Orange landed at Brixham on November 5, 1688, with the intention of dethroning the unpopular and despotic Catholic King James II. William and his army marched on London and James II fled to France. William agreed eventually to accept the crown jointly with his wife Mary Stuart in May 1689. -

Joseph Priestley: Trail-Blazing Experimenter

Chapter 5 JOSEPH PRIESTLEY: TRAIL-BLAZING EXPERIMENTER Goronwy Tudor Jones The First Thirty-one Years oseph Priestley was born near Leeds in Yorkshire on 13th March 1733, Jand continued to live there until he became, at the age of 19, the first student to enrol at the new dissenting academy in Daventry. By the time he left about three years later, along with his main discipline, theology, he had studied philosophy, history, mathematics and science. Furthermore he had gained a working knowledge of six ancient and three modern languages. This formidable intellect was to become one of the most influential men of his time. His varied career took him to Needham Market in Suffolk (1755-58), Nantwich in Cheshire (1758-61), Warrington (1761-67), Leeds (1767-73) and Bowood House in Wiltshire (1773-80) before he came to Birmingham in 1780 for what he described as the happiest period of his life. This ended with the notorious Birmingham Riots of 14th July 1791, Print of Joseph Priestley, 1782, showing which forced Priestley and his family to examples of scientific equipment beneath flee to London. They remained there for the portrait. Priestley Collection by Samuel two years before the continuing hostility Timmins, Birmingham City Archives. 31 Joseph Priestley and Birmingham towards his political and religious views led them, in August 1793, to emigrate to Northumberland, Pennsylvania. There, on 6th February 1804, Priestley died, never having returned to his native England. The same strong religious views were at the heart of Priestley’s decision, at the age of 31 in 1765, to devote a considerable portion of his working life to science.