Friends of the Centre for West Midlands History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Opaque Nature of John Constable's Naturalism

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 12:44 RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review The Opaque Nature of John Constable’s Naturalism Iris Wien The Nature of Naturalism : A Trans-Historical Examination Résumé de l'article La nature du naturalisme : un examen transhistorique Situant les dessins de Constable dans un contexte épistémologique Volume 41, numéro 2, 2016 post-Berkleyien, cet article suggère que le basculement vers une structure représentationnelle, qui met l’accent sur l’écart entre les fonctions figuratives URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1038071ar et picturales, avait été nécessaire pour assurer la prétention à la vérité du DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1038071ar naturalisme de l’artiste. Nous soutenons que les modulations réalistes dans la conceptualisation sémiotique de Berkeley de la perception visuelle furent instrumentales à une esthétique qui s’efforçait d’enligner le langage de la Aller au sommaire du numéro nature avec le sentiment, réconciliant ainsi l’expression subjective et les demandes de l’objectivité. Pourtant, ainsi que nous le démontrons, la rupture d’un ordre de représentation « transparent » qu’opéra Constable eut des Éditeur(s) implications non seulement scientifiques, mais également idéologiques. UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (imprimé) 1918-4778 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Wien, I. (2016). The Opaque Nature of John Constable’s Naturalism. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 41(2), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038071ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

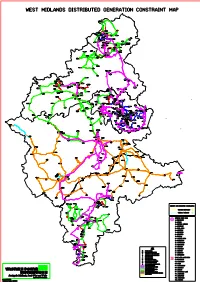

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

8A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8A bus time schedule & line map 8A Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise View In Website Mode The 8A bus line Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Saltley: 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8A bus arriving. Direction: Saltley 8A bus Time Schedule 49 stops Saltley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:59 AM - 11:46 PM Monday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Alum Rock Rd, Saltley Adderley Road, Birmingham Tuesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Saltley Trading Estate, Saltley Wednesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Hereford Square, Birmingham Thursday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Nechells Place, Saltley Friday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM 1 Mainstream Way, Birmingham Saturday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Goodrick Way, Nechells Green Lingard Close, Birmingham Nechells Police Station, Saltley Nechells Place, Birmingham 8A bus Info Direction: Saltley Cromwell St, Nechells Green Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 57 min Cheston Rd, Aston Line Summary: Alum Rock Rd, Saltley, Saltley William Henry street, Birmingham Trading Estate, Saltley, Nechells Place, Saltley, Goodrick Way, Nechells Green, Nechells Police Aston Cross, Aston Station, Saltley, Cromwell St, Nechells Green, Cheston 1 Rocky lane, Birmingham Rd, Aston, Aston Cross, Aston, Upper Sutton St, Aston, Selston Rd, Newtown, Alma St, Newtown, Upper Sutton St, Aston Holte School, Newtown, Lozells St, Lozells, Church Dunsfold Croft, Birmingham St, Hockley, Hockley Circus, Hockley, Barr Street, Hockley, Unett St, Hockley, -

Ludlow - Marriages

LUDLOW - MARRIAGES CURRENT NEW NO. OF REGISTER CONTAINING SOURCE SOURCE REGISTERS 1935 & END DATE OF CLERGY CODE CODE Dates Deposited REGISTER Acton Scott C1 C-L1 0 St Lawrence, Church Stretton C2 C-L2 20.07.1837-10.04.1993 10 4 (21.10.1935) All Stretton PREVIOUSLY ST MICHAEL & ALL SAINTS, NOW ST MICHAEL'S ECUMENICAL PARTNERSHIP C3 C-L3 25.11.1927-25.07.1987 5 1 (30.6.1945) Culmington C4 CL-4 09.02.1838-10.08.1996 1 1 (10.8.1996) Diddlebury C5 C-L5 10.08.1837-14.08.1999 6 2 (22.10.1949) Westhope C6 C-L6 0 Eaton under Heywood C7 C-L7 03.12.1837-22.08.2009 3 1 (3.7.1953) Halford C8 C-L8 23.10.1844-07.08.2004 1 1 (7.8.2004) Hope Bowdler C9 C-L9 28.09.1837-27.05.2006 1 1 (27.5.2006) Munslow C10 C-L10 0 Onibury C11 C-L11 22.02.1838-01.08.1998 1 1 (1.8.1998) Rushbury C12 C-L12 18.12.1837-08.09.2007 1 1 (8.9.2007) Sibdon Carwood C13 C-L13 0 Stokesay C14 C-L14 25.01.1838-28.12.2000 10 2 (10.6.1935) Wistanstow C15 C-L15 01.02.1838-10.10.1998 4 1 (17.03.1945) Cwm Head C16 C-L16 0 Abdon C17 C-L17 19.10.1837-07.08.2004 1 1 (17.08.2004) Ashford Bowdler C18 C-L18 02.03.1840-02.09.2006 1 1 (02.09.2006) Ashford Carbonel C19 C-L19 23.05.1839-10.05.2008 2 1 (28.07.1979) Bitterley C20 C-L20 06.07.1837.16.06.2007 3 1 (30.09.1978) Boraston C21 C-L21 30.09.1837-06.11.1999 5 3 (16.2.1950) Bromfield C22 C-L22 20.07.1837-31.08.1996 1 1 (31.8.1996) Burford C23 C-L23 08.07.1837-03.09.2011 3 1 (18.9.2004) Caynham C24 C-L24 24.07.1837-02.06.2001 1 1 (02.6.2001) Clee St Margaret C25 C-L25 0 Cleeton St Mary C26 C-L26 15.04.1880-24.09.2011 1 1 (24.9.2011) Greete C27 -

Gloving, Philanthropy and the Marrying of Polly. (C) David Walsh 2010, 2013 the Hubbub Came a Hundred Years Later When the Last of the Allcrofts, Jewell, Died in 1992

A forgotten fortune I never grew up with any whisper of gold in the family – no tale of a lost fortune and no hint of amazingly generous presents from distant relatives. The sale of an extraordinary collection of Edwardian travel souvenirs totalling $3 million could have gone un-noticed by me had I not sniffed out the full story a while earlier. My uncle asserted that our distant aunties were Amelia Alcroft and Sophy Martin. The will of Sophy showed otherwise. She was, in 1870, a spinster living with her companion at 4 Ebenezer Terrace, Plumstead, Kent. Despite the clerk’s spidery hand I established that the man charged with proving her estate was an Allcroft, J.D. Allcroft Esquire of 55 Porchester Gate. Could this be somehow relevant to the ‘Amelia Alcroft’ on our tree? I found that this man had left nearly half a million pounds in his estate at his own death, twenty years later. Could this be our forgotten family fortune? Gloving philanthrophy, travel, and the marrying of Polly This chapter begins with a letter sent from a coffee plantation in the Port Royal Mountains, Jamaica in 1853. Polly Martin, 22, and emphatically not Amelia, was sitting at home in her mother’s smart drawing room in Woolwich when the words reached her. Henry Lowry, trying his luck as a mine agent, had gallantly offered to find a husband for his sisters-in-law “to turn mademoiselle into madame” if Polly and Sophy would come out too. They would meet many nice people, he said. He also offered a cuddle to young Georgie, then eight or nine. -

The Environmental Economy of the West Midlands

FINAL REPORT Advantage West Midlands, the Environment Agency and Regional Partners in the West Midlands The Environmental Economy of the West Midlands January 2001 Reference 6738 This report has been prepared by Environmental Resources Management the trading name of Environmental Resources Management Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. In line with our company environmental policy we purchase paper for our documents only from ISO 14001 certified or EMAS verified manufacturers. This includes paper with the Nordic Environmental Label. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 LINKAGES BETWEEN ENVIRONMENT AND THE ECONOMY 1 1.2 STUDY AIMS 1 1.3 THE REGIONAL CONTEXT 1 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT 3 2. STUDY SCOPE 4 2.1 ENVIRONMENTAL INDUSTRY 4 2.2 LAND BASED INDUSTRY 4 2.3 CAPITALISING ON A HIGH QUALITY ENVIRONMENT 4 3. ENVIRONMENTAL INDUSTRY 5 3.1 OVERVIEW 5 3.2 BUSINESSES SUPPLYING ENVIRONMENTAL GOODS & SERVICES 5 3.3 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT IN INDUSTRY 13 3.4 ENVIRONMENTAL POSTS IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR 14 3.5 ENVIRONMENTAL ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS 14 3.6 NON-PROFIT MAKING ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANISATIONS 15 3.7 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION & ENHANCEMENT SECTOR 16 3.8 SUMMARY 18 4. -

HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain | University of Stirling

10/01/21 HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain | University of Stirling HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: View Online Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain E V Macleod Aspinall, A. (1949) Politics and the press, c.1780-1850. Home and Van Thal. Barker, H. (1996) ‘Catering for Provisional Tastes: Newspapers, Readership and Profit in Late Eighteenth-Century England’, Historical Research, 69(168), pp. 42–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.1996.tb01841.x. Barker, H. (2000) ‘Growth of newspapers, IN: Newspapers, politics and English society 1695-1855’, in Newspapers, politics and English society, 1695-1855. Harlow: Longman, pp. 29–45. Barker, Hannah and Chalus, Elaine (1997) Gender in eighteenth-century England: roles, representations and responsibilities. London: Longman. Bennett, Betty T. (1976) British war poetry in the age of romanticism, 1793-1815. New York: Garland Pub. Bindman, D. (1999) ‘Prints’, in An Oxford companion to the Romantic age: British culture, 1776-1832. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 207–213. Bob Harris (1995) ‘The London Evening Post and Mid-Eighteenth-Century British Politics’, The English Historical Review, 110(439), pp. 1132–1156. Available at: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.stir.ac.uk/stable/577253. Bohstedt, J. (1988) ‘GENDER, HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY POLITICS: WOMEN IN ENGLISH RIOTS 1790–1810’, Past and Present, 120(1), pp. 88–122. doi: 10.1093/past/120.1.88. Booth, A. (1977a) ‘FOOD RIOTS IN THE NORTH–WEST OF ENGLAND 1790–1801’, Past and Present, 77(1), pp. 84–107. doi: 10.1093/past/77.1.84. Booth, A. (1977b) ‘FOOD RIOTS IN THE NORTH–WEST OF ENGLAND 1790–1801’, Past and Present, 77(1), pp. -

Three Periods of English Architecture

MBMTRAND SMITHS BOOK STORE M# PACIFIC A VENUS LONG BEACH. CALTP. THREE PERIODS OF <$> ENGLISH ARCHITECTURE. IMPORTED BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS, NEW YORK. THREE PERIODS^ OF ENGLISH ARC HITECTURE BY THOMAS HARRIS F R I B A- FSANI«$> B-T-BATSFORDf LONDON f 1 894 CHISWICK PRESS : —CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. PREFACE. the following pages much is advanced which may- INjustify the charge of lack of novelty. It is, however, the author's intention to be little more than " a gatherer and disposer of other men's stuff," his object being to advance the cause of architectural progress, not so much by enunciating his own views, as by showing how much has been said on the subject by others. This will explain the apparent abruptness of some of the quotations, they being, for the most part, introduced with little attempt at constructive arrangement, where they appeared to best elucidate the text, or to lend the authority of some well- known name to the proposition under consideration ; but they will be found to form a kind of thought mosaic, each one either helping to strengthen, or in some cases to tone down, the others with which it is connected. The progress herein alluded to has found many advo- cates at the Royal Institute of British Architects, and names of the highest repute are associated with it. Archi- tectural publications, both here and in America, have frequently given expression to the longing for relief from the bondage to which the profession has been so long subject, and from the delusions which have militated against the clear apprehension of the destiny of their art. -

Think Property, Think Savills

Telford Open Gardens PRINT.indd 1 PRINT.indd Gardens Open Telford 01/12/2014 16:04 01/12/2014 www.shropshirehct.org.uk www.shropshirehct.org.uk out: Check savills.co.uk Registered Charity No. 1010690 No. Charity Registered [email protected] Email: 2020 01588 640797 01588 Tel. Pam / 205967 07970 Tel. Jenny Contact: [email protected] 01952 239 532 239 01952 group or on your own, all welcome! all own, your on or group Beccy Theodore-Jones Beccy to raise funds for the SHCT. As a a As SHCT. the for funds raise to [email protected] Please join us walking and cycling cycling and walking us join Please 01952 239 500 239 01952 Ride+Stride, 12 September, 2020: 2020: September, 12 Ride+Stride, ony Morris-Eyton ony T 01746 764094 01746 operty please contact: please operty r p a selling or / Tel. Tel. / [email protected] Email: Dudley Caroline from obtained If you would like advice on buying buying on advice like would you If The Trust welcomes new members and membership forms can be be can forms membership and members new welcomes Trust The 01743 367166 01743 Tel. / [email protected] very much like to hear from you. Please contact: Angela Hughes Hughes Angela contact: Please you. from hear to like much very If you would like to offer your Garden for the scheme we would would we scheme the for Garden your offer to like would you If divided equally between the Trust and the parish church. parish the and Trust the between equally divided which offers a wide range of interesting gardens, the proceeds proceeds the gardens, interesting of range wide a offers which One of the ways the Trust raises funds is the Gardens Open scheme scheme Open Gardens the is funds raises Trust the ways the of One have awarded over £1,000,000 to Shropshire churches. -

SHROPSHIRE WAY SOUTH SECTION About Stage 4: Clun to Craven Arms 11 Miles

SHROPSHIRE WAY SOUTH SECTION About Stage 4: Clun to Craven Arms 11 miles Clun Youth Hostel En route to Kempton you will pass Walcot Wood, an ancient woodland managed by the National Trust. Burrow Hill Fort Burrow Hillfort This walk takes in two of the finest Iron Age hill forts in Shropshire, down to quiet unspoilt valleys and over common land that has not been ploughed for centuries. The unspoilt villages in this area were This is regarded by some as superior to Bury Ditches and can be reached by a diversion at immortalised by A. E. Housman in his SO377835 along the edge of a wood. Shropshire Lad: Clunton and Clunbury,Clungunford Hopesay Hopesay Common and Clun, Are the quietest places under the sun. A good place for a rest and if you are Bury Ditches lucky the tea shop opposite the church Bury Ditches Hillfort may be open for some refreshment before another climb to Hopesay Common. The 13th century church with its interesting architecture is worth a visit. Craven Arms This small town on the A49 is a useful for Leave Clun to the north east and climb to Bury rail and bus connections. Here the Heart of Ditches Hill Fort. The Shropshire Way passes Wales railway line veers off towards Swansea. over the ramparts to the central plateau of this Interesting places are The Discovery Centre, The ancient place. It was once obscured by trees Land of Lost Content Museum and Harry Tuffin’s but is now enjoyed by walkers since tree felling the supermarket of the Marches.