The Unexpected Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

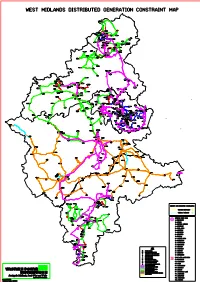

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities -

8A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8A bus time schedule & line map 8A Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise View In Website Mode The 8A bus line Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Saltley: 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8A bus arriving. Direction: Saltley 8A bus Time Schedule 49 stops Saltley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:59 AM - 11:46 PM Monday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Alum Rock Rd, Saltley Adderley Road, Birmingham Tuesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Saltley Trading Estate, Saltley Wednesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Hereford Square, Birmingham Thursday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Nechells Place, Saltley Friday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM 1 Mainstream Way, Birmingham Saturday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Goodrick Way, Nechells Green Lingard Close, Birmingham Nechells Police Station, Saltley Nechells Place, Birmingham 8A bus Info Direction: Saltley Cromwell St, Nechells Green Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 57 min Cheston Rd, Aston Line Summary: Alum Rock Rd, Saltley, Saltley William Henry street, Birmingham Trading Estate, Saltley, Nechells Place, Saltley, Goodrick Way, Nechells Green, Nechells Police Aston Cross, Aston Station, Saltley, Cromwell St, Nechells Green, Cheston 1 Rocky lane, Birmingham Rd, Aston, Aston Cross, Aston, Upper Sutton St, Aston, Selston Rd, Newtown, Alma St, Newtown, Upper Sutton St, Aston Holte School, Newtown, Lozells St, Lozells, Church Dunsfold Croft, Birmingham St, Hockley, Hockley Circus, Hockley, Barr Street, Hockley, Unett St, Hockley, -

APPENDIX 1 Wards Where FPN's Are Issued Constituency Ward Apr May

APPENDIX 1 Wards where FPN's are issued Constituency Ward Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Total Edgbaston Bartley Green 0 0 0 0 Edgbaston 0 0 0 0 Harborne 0 0 0 0 Quinton 0 0 0 0 Erdington Erdington 0 1 0 1 Kingstanding 0 1 0 1 Stockland Green 0 0 2 2 Tyburn 0 1 1 2 Hall Green Hall Green 0 1 0 1 Moseley And Kings Heath 2 0 0 2 Sparkbrook 0 1 1 2 Springfield 0 0 0 0 Hodge Hill Bordesley Green 0 0 0 0 Hodge Hill 0 0 0 0 Shard End 1 4 0 5 Washwood Heath 1 0 0 1 Ladywood Aston 0 2 0 2 Ladywood 459 436 256 1,151 Nechells 5 3 0 8 Soho 5 1 0 6 Northfield Kings Norton 0 0 3 3 Longbridge 0 1 0 1 Northfield 2 0 0 2 Weoley 2 0 0 2 Perry Barr Handsworth Wood 0 0 1 1 Lozells And East Handsworth 0 1 1 2 Oscott 0 2 0 2 Perry Barr 1 0 1 2 Selly Oak Billesley 1 1 0 2 Bournville 0 0 1 1 Brandwood 0 0 0 0 Selly Oak 0 0 1 1 Sutton Coldfield Sutton Four Oaks 0 0 0 0 Sutton New Hall 0 0 0 0 Sutton Trinity 0 0 0 0 Sutton Vesey 0 0 0 0 Yardley Acocks Green 6 6 1 13 Sheldon 0 1 0 1 South Yardley 1 2 1 4 Stechford And Yardley North 1 0 0 1 Total 487 465 270 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1,222 APPENDIX 2 WARD OF PERSON RECEIVING FIXED PENALTY NOTICES BY CONSTITUENCY/WARD It is not possible to provide this information currently and will be provided in the coming weeks Constituency Ward Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Total Edgbaston BARTLEY GREEN 0 EDGBASTON 0 HARBORNE 0 QUINTON 0 Erdington ERDINGTON 0 KINGSTANDING 0 STOCKLAND GREEN 0 TYBURN 0 Hall Green HALL GREEN 0 MOSELEY AND KINGS HEATH 0 SPARKBROOK 0 SPRINGFIELD 0 Hodge Hill BORDESLEY GREEN -

COVID Enforcement Patrols Regular Enforcement Patrols Are Undertaken to Ensure Businesses Are Complying with Coronavirus Legislation

COVID Marshals • 25 COVID Marshals and 8 Park Marshals employed since November providing a hi-vis presence on the street. • Visiting all Wards but are particularly focusing on those with the highest infection rates. • Assisting with surge testing in Great Park and Frankley. • Providing advice to businesses on good practice and to citizens on the use of face coverings. • Eyes and ears for Enforcement Team providing valuable feedback on businesses who are not complying with the legislation so that enforcement work can be prioritised. • Large number of “free” face coverings are being distributed by the COVID Marshals on a daily basis. To date over 18,500 face coverings have been distributed. • Public interactions has now a last fallen considerably since the latest lockdown was introduced. (mid Jan-Feb) • Enclosed shopping centres found to have the highest level of non-compliance with regards to the wearing of face coverings. • Between the 16th Jan and 14th Feb the majority of face coverings (40% - 1,345) were distributed in the City Centre. • 446 masks were distributed by the Park COVID Marshals (13%). PA F 1 1 1 1 1 20 12 20 40 60 80 0 2 4 6 8 GE th 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ace J a 3 n – 14 Acocks Green th Fe Alum Rock b co ( e Aston x c lu Billesley d in v g Bordesley & Highgate L a erings d ywoo Bordesley Green Bournville & Cotteridge d ) Brandwood & King's Heath Bromford & Hodge Hill Castle Vale Erdington distri Frankley Great Park Gravelly Hill Hall Green North Hall Green South but Handsworth Handsworth Wood Harborne ed Holyhead King's Norton North b King's Norton South y w Kingstanding Longbridge & West Heath Lozells ar Moseley Newtown d b Northfield Perry Barr y CO Perry Common Pype Hayes Sheldon Small Heath VID Soho & Jewellery Quarter South Yardley Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Marshals Sparkhill Stirchley Sutton Four Oaks Sutton Mere Green Sutton Trinity Sutton Vesey Tyseley & Hay Mills Weoley & Selly Oak Yardley West & Stechford PA public No 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 12 50 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 GE th 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Jan 4 . -

Newtown, Oscott, Perry Barr, Soho, Oldbury

Equality and Diversity Strategy ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH C5206 GUJARATI Translation 1A ùf PYf #e `eQf WhMf¶\ R¶ÀPe]fHÌ T ]epFh ^A¶ef, Pef Ao¶Ue A¶[l YR¶R¶ Yfb]]e YeKf¶ #pCyfú C5206Wef\h ^Af¶ Pf]h A¶ef$ ½Zz¡PþTf #alò #eUf\e Kf¶z\þVeüT TpW[ U[ VeüT A¶[]e z]þTpPhFrench A¶[ef .................... TranslationC5206 1A BENGALI SiTranslation vous ne 1Apouvez pas lire le document ci-joint, veuillez demander Translation 1B C5206àIf youquelqu'un can not read qui the parle attached anglais document, d'appeler please get ce someone numéro who pour speaks obtenir EnglishPolish deto ring l’aidethis number ………………………… for help ………………………… ùf PYf #e `eQf WhMf¶\ R¶ÀPe]fHÌ T ]epFh ^A¶ef, Pef Ao¶Ue A¶[l YR¶R¶ Yfb]]e YeKf¶ #pCyfú TranslationåKAeM^Wef\h ^Af¶ svzuË Pf]h 1B1A A¶ef$ kAgj-pñAif^ ½Zz¡PþTf &U[ ÁpiM^ HÌOe]f\e pxew^ Kf¶z\þVeüT Mo pArel^, TpW[ U[ áMugòh VeüT A¶[]e ker^ z]þTpPhsAhAezù^r A¶[ef. jMù éver^jI blew^ pAer^M åmM kAõek^ if^ey^ ............................... -

Al Huda Girls' School 74-76 Washwood Heath Road Saltley

IEBT Level 3, Riverside Bishopsgate House Feethams Darlington DL1 5QE The Proprietor Tel no: <redacted> Al Huda Girls' School [email protected] 74-76 Washwood Heath Road Saltley Ref No: 330/6088 Birmingham Date: 24 May 2019 West Midlands B8 1RD Dear Proprietor I refer to the inspection by The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) that was carried out at the above school under section 109 of the Education and Skills Act 2008 on 26 March. You will see from the enclosed report that Ofsted noted serious regulatory failings. Taking account of the report the Secretary of State is satisfied, pursuant to section 114(1) of the Education and Skills Act 2008, that any one or more of the independent school standards1 is or are not being met in relation to the school. In these circumstances I enclose a Notice, served by the Secretary of State for Education under section 114(5) of the 2008 Act, requiring an Action Plan which details the steps that will be taken to meet all of the standards set out in the Annex to the Notice and the time by which each step will be taken, to be submitted by 24 June 2019. You are reminded that the independent school standards require that a copy of the inspection report is sent to parents and a copy is published on the school’s website or, where no such website exists, is provided to parents on request. This will be checked at the next inspection. The Action Plan must contain reasonable timescales for implementation within which the necessary action will be taken and it is expected that the implementation dates given in the Action Plan should not extend beyond 26 August 2019. -

EAST TEAM Gps a to Z

EAST TEAM GPs A TO Z TEL FAX GP SURGERY GP NAME NUMBER NUMBER DN TEAM 0121 0121 WASHWOOD HEATH ALPHA MEDICAL PRACTICE ALVI 328 7010 328 7162 DNs 39 Alum Rock Rd, Alum Rock B8 1JA MUGHAL, DRS SPA 0300 555 1919 0121 0121 WASHWOOD HEATH ALUM ROCK MEDICAL PRACTICE AKHTAR, DR 328 9579 328 7495 DNs 27-28 Highfield RD, B8 3QD SPA 0300 555 1919 0121 0121 WASHWOOD HEATH AMAANAH MEDICAL PRACTICE IQBAL 322 8820 322 8823 DNs Saltley Health Centre KHAN & KHALID Cradock Rd B8 1RZ WAHEED, DRS 0121 0121 ASHFIELD SURGERY BLIGHT 351 3238 313 2509 WALMLEY HC DNs 8 Walmley Road COLLIER Sutton Coldfield B76 1QN LENTON, DRS ASHFURLONG MEDICAL 0121 0121 JAMES PRESTON CNT PRACTICE - SUTTON GROUP SPEAK 354 2032 321 1779 DNs MANOR PRACTICE RIMMER 233 Tamworth Road FLACKS Sutton Coldfield B75 6DX CAVE, DRS 0121 0121 BELCHERS LANE SURGERY AHMAD 722 0383 772 1747 RICHMOND DNs 197 Belchers Lane FARAAZ Bordersley Green B9 5RT KHAN & AZAM, DRS 0121 0121 BUCKLANDS END LANE SURGERY KUMAR 747 2160 747 3425 HODGE HILL DNs 36 Bucklands End Lane SINHA, DRS Castle Brom B34 6BP CASLTE VALE PRIMARY CARE 0121 0121 CENTRE ZAMAN 465 1500 465 1503 CASTLETON DNs 70 Tangmere Drive, Castle Vale B35 7QX SHAH, DRS 0121 0121 CHURCH LANE SURGERY ISZATT 783 2861 785 0585 RICHMOND DNs 113 Church Lane, Stechford B33 9EJ KHAN, DRS 0121 0121 WASHWOOD HEATH COTTERILLS LANE SAIGOL, DR 327 5111 327 5111 DNs 75-77 Cotterills Lane Alum Rock B8 2RZ 0121 0121 DOVE MEDICAL PRACTICE GABRIEL 465 5739 465 5761 DOVEDALE DNs 60 Dovedale Road KALLAN Erdington B23 5DD WRIGHT, DRS EATON WOOD MEDICAL CENTRE -

Birmingham City Council Report of the Acting

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL REPORT OF THE ACTING DIRECTOR OF REGULATION AND ENFORCEMENT TO THE LICENSING AND PUBLIC PROTECTION COMMITTEE 20 JUNE 2018 ALL WARDS PROSECUTIONS AND CAUTIONS – MARCH & APRIL 2018 1. Summary 1.1 This report summarises the outcome of legal proceedings taken by Regulation and Enforcement during the months of March and April 2018. 2. Recommendation 2.1 That the report be noted. Contact Officer: Chris Neville, Acting Director of Regulation and Enforcement Telephone: 0121 464 8640 E-Mail: [email protected] 1 3. Results 3.1 During the months of March and April 2018 the following cases were heard at Birmingham Magistrates Court, unless otherwise stated: . Three Licensing cases were finalised resulting in fines of £1,260 and prosecution costs of £1,268. 14 penalty points were issued and a total of 18 months driving disqualifications were imposed. 37 simple cautions were administered as set out in Appendix 1. 127 Environmental Health cases resulted in fines of £292,196. Prosecution costs of £43,959 were awarded. 9 months imprisonment suspended for 2 years, 12 months disqualification from driving and forfeiture of a vehicle. 4 months imprisonment suspended for 2 years, 4 months tagged curfew and 6 months disqualification from driving. Compensation for clean-up costs in the sum of £1,644 was awarded. One simple caution was administered as set out in Appendix 2. Three Trading Standards cases were finalised resulting in fines of £37,760 and prosecution costs of £12,316. Compensation in the sum of £7,577 was awarded. No simple cautions were administered as set out in Appendix 3. -

Birmingham City Council Strategic Research

Census 2011 What does this mean for Birmingham? Corporate Strategy Team Birmingham City Council Jan 2014 1/24 1 Introduction Data is based on Census 2011 statistics released as of September 2013; with the exception of ONS data sources referenced within the Economy and Diversity sections to support the Census data. Not all Census 2011 statistics have been released, with further data expected through the rest of 2013 and 2014. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 2 2 KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 3 3 ECONOMY .................................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 CENSUS 2011 REVEALS A TRANSITION IN BIRMINGHAM’S ECONOMY ............................................ 4 3.2 BIRMINGHAM UNEMPLOYMENT RISES......................................................................................... 4 3.3 CENSUS 2011 RAISES CONCERNS OF LOW LEVEL OF QUALIFICATIONS FOR BIRMINGHAM ............... 6 3.4 COMMUTERS TRAVEL INTO BIRMINGHAM .................................................................................... 6 3.5 DEPRIVATION ........................................................................................................................... 7 4 BIRMINGHAM – A SUPER DIVERSE CITY .................................................................................