Drugs in the West Midlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

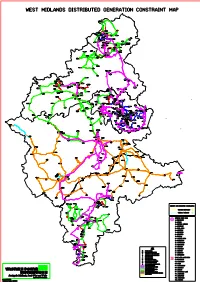

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

8A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8A bus time schedule & line map 8A Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise View In Website Mode The 8A bus line Birmingham Inner Circle Anticlockwise has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Saltley: 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8A bus arriving. Direction: Saltley 8A bus Time Schedule 49 stops Saltley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:59 AM - 11:46 PM Monday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Alum Rock Rd, Saltley Adderley Road, Birmingham Tuesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Saltley Trading Estate, Saltley Wednesday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Hereford Square, Birmingham Thursday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Nechells Place, Saltley Friday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM 1 Mainstream Way, Birmingham Saturday 4:49 AM - 11:46 PM Goodrick Way, Nechells Green Lingard Close, Birmingham Nechells Police Station, Saltley Nechells Place, Birmingham 8A bus Info Direction: Saltley Cromwell St, Nechells Green Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 57 min Cheston Rd, Aston Line Summary: Alum Rock Rd, Saltley, Saltley William Henry street, Birmingham Trading Estate, Saltley, Nechells Place, Saltley, Goodrick Way, Nechells Green, Nechells Police Aston Cross, Aston Station, Saltley, Cromwell St, Nechells Green, Cheston 1 Rocky lane, Birmingham Rd, Aston, Aston Cross, Aston, Upper Sutton St, Aston, Selston Rd, Newtown, Alma St, Newtown, Upper Sutton St, Aston Holte School, Newtown, Lozells St, Lozells, Church Dunsfold Croft, Birmingham St, Hockley, Hockley Circus, Hockley, Barr Street, Hockley, Unett St, Hockley, -

COVID Enforcement Patrols Regular Enforcement Patrols Are Undertaken to Ensure Businesses Are Complying with Coronavirus Legislation

COVID Marshals • 25 COVID Marshals and 8 Park Marshals employed since November providing a hi-vis presence on the street. • Visiting all Wards but are particularly focusing on those with the highest infection rates. • Assisting with surge testing in Great Park and Frankley. • Providing advice to businesses on good practice and to citizens on the use of face coverings. • Eyes and ears for Enforcement Team providing valuable feedback on businesses who are not complying with the legislation so that enforcement work can be prioritised. • Large number of “free” face coverings are being distributed by the COVID Marshals on a daily basis. To date over 18,500 face coverings have been distributed. • Public interactions has now a last fallen considerably since the latest lockdown was introduced. (mid Jan-Feb) • Enclosed shopping centres found to have the highest level of non-compliance with regards to the wearing of face coverings. • Between the 16th Jan and 14th Feb the majority of face coverings (40% - 1,345) were distributed in the City Centre. • 446 masks were distributed by the Park COVID Marshals (13%). PA F 1 1 1 1 1 20 12 20 40 60 80 0 2 4 6 8 GE th 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ace J a 3 n – 14 Acocks Green th Fe Alum Rock b co ( e Aston x c lu Billesley d in v g Bordesley & Highgate L a erings d ywoo Bordesley Green Bournville & Cotteridge d ) Brandwood & King's Heath Bromford & Hodge Hill Castle Vale Erdington distri Frankley Great Park Gravelly Hill Hall Green North Hall Green South but Handsworth Handsworth Wood Harborne ed Holyhead King's Norton North b King's Norton South y w Kingstanding Longbridge & West Heath Lozells ar Moseley Newtown d b Northfield Perry Barr y CO Perry Common Pype Hayes Sheldon Small Heath VID Soho & Jewellery Quarter South Yardley Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Marshals Sparkhill Stirchley Sutton Four Oaks Sutton Mere Green Sutton Trinity Sutton Vesey Tyseley & Hay Mills Weoley & Selly Oak Yardley West & Stechford PA public No 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 12 50 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 GE th 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Jan 4 . -

Birmingham City Council Strategic Research

Census 2011 What does this mean for Birmingham? Corporate Strategy Team Birmingham City Council Jan 2014 1/24 1 Introduction Data is based on Census 2011 statistics released as of September 2013; with the exception of ONS data sources referenced within the Economy and Diversity sections to support the Census data. Not all Census 2011 statistics have been released, with further data expected through the rest of 2013 and 2014. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 2 2 KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 3 3 ECONOMY .................................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 CENSUS 2011 REVEALS A TRANSITION IN BIRMINGHAM’S ECONOMY ............................................ 4 3.2 BIRMINGHAM UNEMPLOYMENT RISES......................................................................................... 4 3.3 CENSUS 2011 RAISES CONCERNS OF LOW LEVEL OF QUALIFICATIONS FOR BIRMINGHAM ............... 6 3.4 COMMUTERS TRAVEL INTO BIRMINGHAM .................................................................................... 6 3.5 DEPRIVATION ........................................................................................................................... 7 4 BIRMINGHAM – A SUPER DIVERSE CITY ................................................................................. -

Pharmacy Minor Ailment Scheme

The Pharmacy Minor Ailments Service covers the following conditions Minor Ailment/Condition Acute Cough under 16 and over 16 Acute Fever under 16 Acute Bacterial Conjunctivitis under 16 and over 16 Acute Pain / Earache/Headache/ Temperature over 16 Athletes Foot under 16 and over 16 Bites and Stings and Allergies under 16 and over 16 Cold sores under 16 and over 16 Cold and Flu under 16 and over 16 Constipation under 16 and over 16 Cystitis over 16 Diarrhoea under 16 and over 16 Dry Skin (Simple Eczema) under 16 Dermatitis/Allergic type rashes under 16 and over 16 Earache under 16 Earwax under 16 and over 16 Hay Fever under 16 and over 16 Heartburn/Indigestion over 16 Haemorrhoids over 16 Infant Decongestant under 16 Mouth Ulcers and Teething under 16 Mouth Ulcers over 16 Nappy Rash under 16 Oral Thrush under 16 and over 16 Scabies under 16 and over 16 Sore Throat over 16 Sprains and Strains over 16 Sunburn under 16 Threadworm under 16 and over 16 Vaginal Thrush over 16 Warts and Verruca’s under 16 Participating Pharmacies in the Sandwell and West Birmingham area: Pharmacy Name Pharmacy Address Postcode Al-Shafa Pharmacy 93 Shireland Road, Smethwick B66 4QJ Al-Shifa Pharmacy 164 Lozells Rd, Birmingham B19 2SX ASDA Pharmacy within ASDA store off Windmill Lane, Smethwick, Birmingham B66 3EN ASDA Pharmacy within ASDA store Old Park Lane, Oldbury, West Midlands B69 4PU ASDA Pharmacy within ASDA store One Stop Shopping Centre, Walsall Road, Perry Barr, Birmingham B42 1AB ASDA Pharmacy within ASDA Superstore Wednesbury Oak Road, Tipton DY4 -

The Unexpected Community

The Unexpected Community: The Needs and Aspirations of Birmingham’s Somali Community Adrian Jones MAIN AUTHOR Adrian Jones is a freelance Housing Consultant. He is also a member of the DCLG Expert Housing Panel, and a Human City Institute Associate. Adrian has published widely on housing and BME issues. WITH CONTRIBUTIONS AND SUPPORT FROM Kevin Gulliver is an independent Housing and Regeneration Consultant and Research and Development Director of the Human City Institute. John Morris is Chief Executive of Trident Housing Association and Vice-Chair of the Human City Institute. The author would also like to thank everyone from Birmingham’s Somali community for helping, for AMANA for facilitating and for Birmingham City Council for providing such useful information. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publishers. While all reasonable care and attention has been taken in preparing this report, the Human City Institute regrets that it cannot assume responsibility for any errors or omissions. The views expressed are those of the authors. © Human City Institute ISBN 978-1-906149-06-2 First published in September 2007 by the Human City Institute 239, Holliday Street, Birmingham B1 1SJ Edited and designed by Kevin Gulliver. Cover and print by Call Print. CONTENTS FOREWORD by John Morris & Hassan Dimbil 1 About This Report 2 SUMMARY 3 1. Birmingham’s Somali Community 10 Introduction 10 Demographic Characteristics 11 2. Housing: Key Issues 14 Overview 14 Household Type, Tenure and Social Status 15 Private Rented Sector 19 Social Rented Sector 20 Homelessness 26 Housing Conditions and Suitability 30 3. -

Evidencing Method Gamma Will Provide Outlined Learning

SUCCESSFUL DELIVERY REWARD CRITERIA REPORT EVIDENCING METHOD GAMMA WILL PROVIDE OUTLINED LEARNING SUCCESSFUL DELIVERY REWARD CRITERIA REPORT EVIDENCING METHOD GAMMA WILL PROVIDE OUTLINED LEARNING Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 2 Progress and learning to date of Method Alpha and Method Beta (Criterion i) .................................................... 5 2.1 Progress and learning to date of Method Alpha ............................................................................................. 5 2.1.1 Integration of Methods ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Progress and learning to date of Method Beta ............................................................................................... 8 3 Proposed Methodology for Method Gamma (Criterion ii) ................................................................................... 10 3.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 10 3.2 Method Gamma Substations ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.3 Technology Overview ................................................................................................................................... -

Mapping of Race and Poverty in Birmingham

MAPPING OF RACE AND POVERTY IN BIRMINGHAM Alessio Cangiano – ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS, University of Oxford) II Table of contents Executive Summary p. 1 1. Introduction p. 3 2. Population characteristics and demographic dynamics p. 3 3. Geographical patterns of deprivation across the city p. 5 4. Socio-economic outcomes of different ethnic groups at ward level p. 7 4.1. Access to and outcomes in the labour market p. 7 4.2. Social and health conditions p. 9 4.3. Housing p.10 5. Public spending for benefits, services and infrastructures p.11 5.1. Benefit recipients p.11 5.2. Strategic planning p.11 6. Summary and discussion p.13 6.1. Data gaps p.13 6.2. Deprivation across Birmingham wards p.14 6.3. Deprivation across ethnic groups p.14 6.4. Relationship between poverty and ethnicity p.15 6.5. Consequences of demographic trends p.15 6.6. Impact of benefits and local government’s spending p.16 References p.17 III List of figures Figure 1 – Population by ethnic group, Birmingham mid-2004 (%) p.18 Figure 2.1 – Population change, Birmingham 2001-2004 (thousand) p.18 Figure 2.2 – Population change, Birmingham 2001-2004 (Index number, 2001=100) p.19 Figure 3 – Foreign-born population by ethnic group, Birmingham 2001 (%) p.19 Figure 4 – Age pyramids of the main ethnic groups in Birmingham, 2001 (%) p.20 Figure 5 – Distribution of the major ethnic groups across Birmingham wards, 2001 (absolute numbers) p.25 Figure 6 – Population by ethnic group in selected Birmingham wards, 2001 (%) p.27 Figure 7 – Indices of Deprivation, -

Sparkbrook and Small Heath

The Birmingham Plan BIRMINGHAM UNITARY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2005 (incorporating Alterations approved by the City Council for adoption on 11 October 2005) CHAPTER 17 - SPARKBROOK AND SMALL HEATH General Character 17.1 The Sparkbrook and Small Heath Constituency extends south-eastwards from the City Centre to Hall Green and Moseley. Edgbaston lies to the west of the Constituency and Solihull Metropolitan Borough forms the eastern boundary. The Highgate district lies within the Ring Road and is, therefore, dealt with in the City Centre Statement. The Constituency had a population of around [77,000] 107,000 in [1987] 1991, including a large ethnic minority community. Key statistics relating to the Constituency are included in the table at the end of this chapter. 17.2 A number of roads which serve the Constituency fall within the strategic highway network; these are: • Small Heath [By-Pass,] Highway which forms part of the A45 link between the City Centre and the National Exhibition Centre and Birmingham International Airport. • Warwick Road (A41) linking the City Centre with Solihull and the M42. • Moseley Road (A435) which links with Redditch and the M42. • Stratford Road (A34) which is a major southern entry point to the City. • The Outer Orbital Route (A4040). In addition, it is served by the Birmingham to Leamington Spa and North Warwickshire railway lines. 17.3 The major land use in the Constituency is residential and comprises a wide range of housing types. There are areas of pre-1919 terraced housing, which have been the focus of extensive urban renewal activity, [extend on] in Small Heath, Sparkhill and Sparkbrook either side of Stratford Road, with areas of more prosperous housing in Moseley and Acocks Green. -

R Submissions to the Birmingham City Council Electoral Review

Local Residents Q - R submissions to the Birmingham City Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents with surnames beginning with Q - R. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. 5/19/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: adib qassim E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: hall green wasnt broken, i really dont understand why your doing this. now youve made hall green north part of tyseley and haymills and split it from south. tyseley and haymills are not hall green, who are you trying to fool. keep the old hall green ward and make a new ward for tyseley and haymills (they do fit together). Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8019 1/1 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: Anne Quirk E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: My opinion is that Balden Rd should become part of Harborne Ward Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8308 1/1 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: Naeem Qureshi E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: I wish to endorse the boundary commission for the Sparkbrook Ward. It is clear that the boundary commission has taken the views of the public consultation to ensure the new ward reflects community interests, identities and boundaries that is relevant and fit for purpose.