Download Birmingham | Strategic Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

38/40 Cherrywood Road, Bordesley Green, Birmingham, B9 4Ud

38/40 CHERRYWOOD ROAD, BORDESLEY GREEN, BIRMINGHAM, B9 4UD FREEHOLD FOR SALE GROUND FLOOR PORTAL FRAMED INDUSTRIAL/WAREHOUSE ACCOMMODATION 10,314 sq.ft/958.19 sq.m • Prominent position/extensive frontage onto Cherrywood Road. • Forecourt, off-street loading/car parking. • Circa 2.5 miles east of Birmingham City Centre. • Circa 2.75 miles from the main Aston Expressway (A38M). • Within close proximity to the Heartlands spine road (A47). Stephens McBride Chartered Surveyors & Estate Agents • Within close proximity to the middle ring One, Swan Courtyard, Coventry Road, Birmingham, B26 1BU road. Tel: 0121 706 7766 Fax: 0121 706 7796 www.smbsurveyors.com 38/40 CHERRYWOOD ROAD, BORDESLEY GREEN, BIRMINGHAM, B9 4UD LOCATION Solid concrete floor structure. Excellent natural light. The subject premises occupies a prominent position, enjoying an extensive frontage onto Cherrywood Road. Forecourt, off-street loading/car parking. Cherrywood Road provides direct access to the ACCOMMODATION main Bordesley Green (B4128), which in conjunction with Coventry Road/Cattell Road, 10,314 sq.ft/958.19 sq.m provides direct access to Bordesley Circus (Middle Ring Road – A4540 – Bordesley/Watery Lane MAINS SUPPLIES Middleway). The property has the advantage of mains electricity Birmingham City Centre is situated approximately (3 phase), gas, water and drainage. 2 ½ miles due west. RATEABLE VALUE/RATES PAYABLE The property is within relative close proximity to the main Aston Expressway (A38M) and the Rateable value: £22,250 Heartlands Spine Road (A47). Rates payable circa: £10,900 Junction 6 of the M6 motorway, “Spaghetti VAT Junction” is situated approximately 2.75 miles due north. We are advised that VAT is not applicable. -

West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner Register of Gifts And

West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner Register of Gifts and Hospitality - Police and Crime Commissioner and Deputy Police and Crime Commissioner Note: This register contains details of declarations made by the PCC and DPCC and includes details of offers of gifts and hospitality not accepted Name Name of person or organisation Details of Gift or hospitality Estimate of value Date offer received Comments Funeral for Don Jones partner to Cllr Diana refreshments offered after Bob Jones Holl-Allen funeral £10.00 23/11/2012 declined passed to office staff for Bob Jones Harmeet Singh Bhakna Punjabi News Indian Sweets £5.00 23/11/2012 consumption Bob Jones Asian Business Forum Samosas and pakoras offered £7.00 28/11/2012 refreshments consumed Bob Jones Home office PCC welcome Buffet lunch provided £7.00 03/12/2012 refreshments consumed Bob Jones APPG on Polcing meeting Buffett and wine offered £10.00 03/12/2012 buffet consumed, wine declined Bob Jones Connect Public Affairs lunch buffet offered £12.00 04/12/2012 Buffet consumed Annual Karate Awards presentation Bob Jones evening food and drink offered £12.00 07/12/2012 food and drink declined invite to Brisitsh Police Symphony Orchestra BPSO accepted but ticket unavailable on Yvonne Mosquito Steria sponsors Proms night special £21.00 08/12/2012 the evening Gavin Chapman and John Torrie - Steria Invite to supper at Hotel du Vin Yvonne Mosquito sponsors flollowing BPSO Proms £30.00 08/12/2012 declined Christmas lunch and drink offered. Small comemorative food consumed, Alcohol declined, Bob -

Birmingham Mental Health Recovery and Employment Service Prospectus - 2018

Birmingham Mental Health Recovery and Employment Service Prospectus - 2018 Hope - Control - Opportunity Birmingham Mental Health Recovery Service The Recovery Service offers recovery and wellbeing sessions to support mental, physical and emotional wellbeing in shared learning environments in the community. It will support people to identify and build on their own strengths and make sense of their experiences. This helps people take control, feel hopeful and become experts in their own wellbeing and recovery. Education and Shared Learning The Recovery Service provides an enablement approach to recovery, with an aim to empower people to live well through shared learning. As human beings we all experience our own personal recovery journeys and can benefit greatly from sharing and learning from each other in a safe and equal space. Co-production We aim for all courses to be developed and/or delivered in partnership with people who have lived experience (i.e. of mental health issues and/ or learning disabilities) or knowledge of caring for someone with these experiences. This model of shared learning allows for rich and diverse perspectives on living well with mental health or related issues. Eligibility This service shall be provided to service users who are: • Aged 18 years and above • Registered with a Birmingham GP for whom the commissioner is responsible for funding healthcare services • Residents of Birmingham registered with GP practices within Sandwell and West Birmingham CCG • Under the care of secondary mental health services or on the GP Serious Mental Illness register. Principles of Participation 1. Treat all service users and staff with compassion, dignity and respect and to not discriminate against or harass others at any time, respecting their rights, life choices, beliefs and opinions. -

145 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

145 bus time schedule & line map 145 Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich View In Website Mode The 145 bus line (Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bromsgrove: 5:26 PM (2) Bromsgrove: 8:00 AM (3) Droitwich Spa: 7:22 AM - 4:56 PM (4) Longbridge: 6:45 AM - 6:10 PM (5) Rubery: 9:13 AM - 12:50 PM (6) Wychbold: 6:16 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 145 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 145 bus arriving. -

4506 18 Draft Attachment 01.Pdf

West Midlands Police Freedom of Information POLICE STATIONS & BEAT OFFICES CLOSED SINCE APRIL 2010 DATE CURRENT CLOSED PROPERTY ADDRESS STATUS 20/05/2010 BORDESLEY GREEN POLICE STATION 280-282 Bordesley Green, Birmingham B9 5NA SOLD 20/5/10 27/07/2010 NORTHGATE BO 32 Northgate, Cradley Heath B64 6AU AGREEMENT TERMINATED 01/08/2010 BRAMFORD PRIMARY SCHOOL BO Park Road, Woodsetton, Dudley DY1 4JH AGREEMENT TERMINATED ST THOMAS'S COMMUNITY NETWORK 01/08/2010 Beechwood Road, Dudley DY2 7QA AGREEMENT TERMINATED BO 22/09/2010 WALKER ROAD BO 115 Walker Road, Blakenall, Walsall WS3 1DB AGREEMENT TERMINATED 23/09/2010 GREENFIELD CRESCENT BO 10 Greenfield Crescent, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 3AU AGREEMENT TERMINATED 26/10/2010 EVERDON ROAD BO 40 Everdon Road, Coventry CV6 4EF AGREEMENT TERMINATED 08/11/2010 MERRY HILL BO Unit U56B Upper Mall Phase 5, Merry Hill Centre, Dudley DY5 1QX AGREEMENT TERMINATED 03/02/2011 COURTAULDS BO 256 Foleshill Road, Great Heath, Coventry CV6 5AB AGREEMENT TERMINATED 25/02/2011 ASTON FIRE STATION NURSERY BO The Nursery Building, Ettington Road, Aston, Birmingham B6 6ED AGREEMENT TERMINATED 28/02/2011 BLANDFORD ROAD BO 125 Blandford Road, Quinton, Birmingham B32 2LT AGREEMENT TERMINATED 05/04/2011 LOZELLS ROAD BO 173A Lozells Road, Lozells, Birmingham B19 1RN AGREEMENT TERMINATED 30/06/2011 LANGLEY BO Albright & Wilson, Station Road, Langley, Oldbury B68 0NN AGREEMENT TERMINATED BILSTON POLICE STATION 10/08/2011 15 Mount Pleasant, Bilston WV14 7LJ SOLD 10/8/11 (old) HOLLYHEDGE HOUSE & MEWS 05/09/2011 2 Hollyhedge Road, -

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01

Information for Partner Institutions Incoming Postgraduate Exchange Students 2019- 2020 Address Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website www.abs.aston.ac.uk Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01 KEY CONTACTS: Saskia Hansen Institutional Erasmus Coordinator Pro-Vice Chancellor International Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 4664 Email: [email protected] Aston Business School Professor George Feiger Executive Dean Email Rebecca Okey Email: [email protected] Associate Dean Dr Geoff Parkes International Email: [email protected] International Relations Selena Teeling Manager Email: [email protected] Incoming and Outgoing International and Student Exchange Students Development Office Tel: ++44 (0) 121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate Student Elsa Zenatti-Daniels Development Lead Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] International and Student Ellie Crean Development Coordinator Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3255 Email: [email protected] Contents Academic Information Important Dates 2 Entry Requirements 4 Application Procedures: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 5 Application Procedures: Double Degree Students 7 Credits and Course Layout 8 Study Methods and Grading System 9 MSc Module Selection: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 10 Course Selection: Double Degrees 11 The Aston Edge (MSc Double Degree) 12 Induction and Erasmus Form Details 13 Conditions for Eligibility 14 Practical Information Visas and Health Insurance 16 Accommodation 17 Support Facilities 20 Student Life at Aston 21 Employments and Careers Services 22 Health and Well Being at Aston 23 Academic Information Important Dates APPLICATION DEADLINES The nomination deadline for the fall term will be 1 June 2019 and the application deadline will be 20 June 2019 for double degree and Term 1 exchange students. -

X21 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X21 bus time schedule & line map X21 Birmingham - Woodcock Hill via Weoley Castle View In Website Mode The X21 bus line (Birmingham - Woodcock Hill via Weoley Castle) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birmingham: 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM (2) Woodcock Hill: 6:20 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X21 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X21 bus arriving. Direction: Birmingham X21 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Birmingham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:59 AM - 10:54 PM Monday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Shenley Fields Drive, Woodcock Hill Tuesday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Bartley Drive, Woodcock Hill Wednesday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Cromwell Lane, Bangham Pit Thursday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Moors Lane, Birmingham Friday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Moors Lane, Bangham Pit Hillwood Road, Birmingham Saturday 5:10 AM - 11:44 PM Woodcock Lane, Bangham Pit Draycott Drive, Bangham Pit Long Nuke Road, Birmingham X21 bus Info Direction: Birmingham Shenley Academy, Woodcock Hill Stops: 42 Long Nuke Road, Birmingham Trip Duration: 39 min Line Summary: Shenley Fields Drive, Woodcock Hill, Fulbrook Grove, Woodcock Hill Bartley Drive, Woodcock Hill, Cromwell Lane, Somerford Road, Birmingham Bangham Pit, Moors Lane, Bangham Pit, Woodcock Lane, Bangham Pit, Draycott Drive, Bangham Pit, Marston Rd, Woodcock Hill Shenley Academy, Woodcock Hill, Fulbrook Grove, Austrey Grove, Birmingham Woodcock Hill, Marston Rd, Woodcock Hill, Quarry Rd, Weoley Castle, Ruckley Rd, Weoley Castle, Quarry Rd, Weoley Castle Gregory Ave, Weoley -

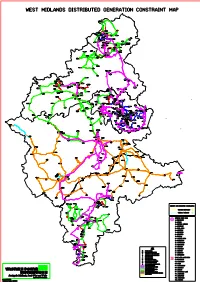

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

Birmingham a Powerful City of Spirit

Curriculum Vitae Birmingham A powerful city of spirit Bio Timeline of Experience Property investment – As the second largest city in the UK, I have a lot to offer. I have great Birmingham, UK connections thanks to being so centrally located, as over 90% of the UK market is only a four hour drive away. The proposed HS2 railway is poised I’ve made a range to improve this further – residents will be able to commute to London in of investments over less than an hour. I thrive in fast-paced environments, as well as calmer the years. The overall waters – my vast canal route covers more miles than the waterways average house price is of Venice. £199,781, up 6% up 2018 - 2019 - 2019 2018 on the previous year. Truly a national treasure, my famed Jewellery Quarter contains over 800 businesses specialising in handcrafted or vintage jewellery and produces 40% of the UK’s jewellery. Edgbaston is home to the famed cricket ground Job application surge – and sees regular county matches, alongside the England cricket team for Birmingham, UK international or test matches. My creative and digital district, the Custard I’ve continued to refine Factory, is buzzing with artists, innovators, developers, retailers, chefs and my Sales and Customer connoisseurs of music. Other key trades include manufacturing (largely Service skills, seeing a cars, motorcycles and bicycles), alongside engineering and services. rise in job applications of 34% and 29% between May 2018 2018 - 2019 2018 Education Skills and January 2019. 4 I have an international Launch of Birmingham Festivals – universities including the perspective, with Brummies Birmingham, UK University of Birmingham, Aston, hailing from around the world Newman and Birmingham City. -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities