Three Periods of English Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde

87T" ACSA ANNUAL MEETING 125 Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde ELIZABETH C. ENGLISH University of Pennsylvania THE CONTEXT OF THE DEBATES BETWEEN Gogol and Nikolai Nadezhdin looked for ways for architecture to THE WESTERNIZERS AND THE SLAVOPHILES achieve unity out of diverse elements, such that it expressed the character of the nation and the spirit of its people (nnrodnost'). In the teaching of Modernism in architecture schools in the West, the Theories of art became inseparably linked to the hotly-debated historical canon has tended to ignore the influence ofprerevolutionary socio-political issues of nationalism, ethnicity and class in Russia. Russian culture on Soviet avant-garde architecture in favor of a "The history of any nation's architecture is tied in the closest manner heroic-reductionist perspective which attributes Russian theories to to the history of their own philosophy," wrote Mikhail Bykovskii, the reworking of western European precedents. In their written and Nikolai Dmitriev propounded Russia's equivalent of Laugier's manifestos, didn't the avantgarde artists and architects acknowledge primitive hut theory based on the izba, the Russian peasant's log hut. the influence of Italian Futurism and French Cubism? Imbued with Such writers as Apollinari Krasovskii, Pave1 Salmanovich and "revolutionary" fervor, hadn't they publicly rejected both the bour- Nikolai Sultanov called for "the transformation. of the useful into geois values of their predecessors and their own bourgeois pasts? the beautiful" in ways which could serve as a vehicle for social Until recently, such writings have beenacceptedlargelyat face value progress as well as satisfy a society's "spiritual requirements".' by Western architectural historians and theorists. -

1 Dataset Illustration

1 Dataset Illustration The images are crawled from Wikimedia. Here we summary the names, index- ing pages and typical images for the 66-class architectural style dataset. Table 1: Summarization of the architectural style dataset. Url stands for the indexing page on Wikimedia. Name Typical images Achaemenid architecture American Foursquare architecture American craftsman style Ancient Egyptian architecture Art Deco architecture Art Nouveau architecture Baroque architecture Bauhaus architecture 1 Name Typical images Beaux-Arts architecture Byzantine architecture Chicago school architecture Colonial architecture Deconstructivism Edwardian architecture Georgian architecture Gothic architecture Greek Revival architecture International style Novelty 2 architecture Name Typical images Palladian architecture Postmodern architecture Queen Anne architecture Romanesque architecture Russian Revival architecture Tudor Revival architecture 2 Task Description 1. 10-class dataset. The ten datasets used in the classification tasks are American craftsman style, Baroque architecture, Chicago school architecture, Colonial architecture, Georgian architecture, Gothic architecture, Greek Revival architecture, Queen Anne architecture, Romanesque architecture and Russian Revival architecture. These styles have lower intra-class vari- ance and the images are mainly captured in frontal view. 2. 25-class dataset. Except for the ten datasets listed above, the other fifteen styles are Achaemenid architecture, American Foursquare architecture, Ancient Egyptian architecture, -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Old San Juan

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Old San Juan Historic District/Distrito Histórico del Viejo San Juan Other Name/Site Number: Ciudad del Puerto Rico; San Juan de Puerto Rico; Viejo San Juan; Old San Juan; Ciudad Capital; Zona Histórica de San Juan; Casco Histórico de San Juan; Antiguo San Juan; San Juan Historic Zone 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Western corner of San Juan Islet. Roughly bounded by Not for publication: Calle de Norzagaray, Avenidas Muñoz Rivera and Ponce de León, Paseo de Covadonga and Calles J. A. Corretejer, Nilita Vientos Gastón, Recinto Sur, Calle de la Tanca and del Comercio. City/Town: San Juan Vicinity: State: Puerto Rico County: San Juan Code: 127 Zip Code: 00901 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X_ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 699 128 buildings 16 6 sites 39 0 structures 7 19 objects 798 119 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 772 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form ((Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Plaaces Registration Form 4. -

Gloving, Philanthropy and the Marrying of Polly. (C) David Walsh 2010, 2013 the Hubbub Came a Hundred Years Later When the Last of the Allcrofts, Jewell, Died in 1992

A forgotten fortune I never grew up with any whisper of gold in the family – no tale of a lost fortune and no hint of amazingly generous presents from distant relatives. The sale of an extraordinary collection of Edwardian travel souvenirs totalling $3 million could have gone un-noticed by me had I not sniffed out the full story a while earlier. My uncle asserted that our distant aunties were Amelia Alcroft and Sophy Martin. The will of Sophy showed otherwise. She was, in 1870, a spinster living with her companion at 4 Ebenezer Terrace, Plumstead, Kent. Despite the clerk’s spidery hand I established that the man charged with proving her estate was an Allcroft, J.D. Allcroft Esquire of 55 Porchester Gate. Could this be somehow relevant to the ‘Amelia Alcroft’ on our tree? I found that this man had left nearly half a million pounds in his estate at his own death, twenty years later. Could this be our forgotten family fortune? Gloving philanthrophy, travel, and the marrying of Polly This chapter begins with a letter sent from a coffee plantation in the Port Royal Mountains, Jamaica in 1853. Polly Martin, 22, and emphatically not Amelia, was sitting at home in her mother’s smart drawing room in Woolwich when the words reached her. Henry Lowry, trying his luck as a mine agent, had gallantly offered to find a husband for his sisters-in-law “to turn mademoiselle into madame” if Polly and Sophy would come out too. They would meet many nice people, he said. He also offered a cuddle to young Georgie, then eight or nine. -

Think Property, Think Savills

Telford Open Gardens PRINT.indd 1 PRINT.indd Gardens Open Telford 01/12/2014 16:04 01/12/2014 www.shropshirehct.org.uk www.shropshirehct.org.uk out: Check savills.co.uk Registered Charity No. 1010690 No. Charity Registered [email protected] Email: 2020 01588 640797 01588 Tel. Pam / 205967 07970 Tel. Jenny Contact: [email protected] 01952 239 532 239 01952 group or on your own, all welcome! all own, your on or group Beccy Theodore-Jones Beccy to raise funds for the SHCT. As a a As SHCT. the for funds raise to [email protected] Please join us walking and cycling cycling and walking us join Please 01952 239 500 239 01952 Ride+Stride, 12 September, 2020: 2020: September, 12 Ride+Stride, ony Morris-Eyton ony T 01746 764094 01746 operty please contact: please operty r p a selling or / Tel. Tel. / [email protected] Email: Dudley Caroline from obtained If you would like advice on buying buying on advice like would you If The Trust welcomes new members and membership forms can be be can forms membership and members new welcomes Trust The 01743 367166 01743 Tel. / [email protected] very much like to hear from you. Please contact: Angela Hughes Hughes Angela contact: Please you. from hear to like much very If you would like to offer your Garden for the scheme we would would we scheme the for Garden your offer to like would you If divided equally between the Trust and the parish church. parish the and Trust the between equally divided which offers a wide range of interesting gardens, the proceeds proceeds the gardens, interesting of range wide a offers which One of the ways the Trust raises funds is the Gardens Open scheme scheme Open Gardens the is funds raises Trust the ways the of One have awarded over £1,000,000 to Shropshire churches. -

Further Information Winds Along the Top of the Escarpment Enclosed Parkland

Further Information winds along the top of the escarpment enclosed parkland. Please take care 19 Go right past the gate onto a track for the waymark post as there are in the wood. Cross the next stile when walking through the farmyard to take a stile on the right and cut several false turnings here). Climb for Shropshire Hills Discovery Centre and keep left away from the edge and keep to the waymarked route. diagonally across the fields to Sallow a short distance to turn left and follow School Road, Craven Arms SY7 9RS following the narrow path. Coppice. the footpath along the bottom of the +44 (0) 1588 676010 Cross the farmyard passing the 13 wood. [email protected] To your right the sheer limestone cliff resembles the farmhouse on your left to follow 20 Go over the stile into the wood bearing THREE WOODS www.shropshirehillsdiscoverycentre.co.uk Wenlock Edge that runs in an unbroken line from the lane down to the main road. right. Take the next right to follow a ‰ Ignore all turnings until you reach the Travel information Craven Arms to Much Wenlock. The rock has been Cross the road and the narrow path around the eastern side of the turning at the top of the track at WALK Mainline railway stations are at Shrewsbury, Church quarried in many places to be ‘burned’ to make slake footbridge to the left of the main wood (keep right). Eventually you point 4. Stretton, Craven Arms and Ludlow. For bus and train lime for ‘sweetening’ fields and making lime-wash and bridge. -

Neoclassical Architecture 1 Neoclassical Architecture

Neoclassical architecture 1 Neoclassical architecture Neoclassical architecture was an architectural style produced by the neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century, both as a reaction against the Rococo style of anti-tectonic naturalistic ornament, and an outgrowth of some classicizing features of Late Baroque. In its purest form it is a style principally derived from the architecture of Classical Greece and the architecture of Italian Andrea Palladio. The Cathedral of Vilnius (1783), by Laurynas Gucevičius Origins Siegfried Giedion, whose first book (1922) had the suggestive title Late Baroque and Romantic Classicism, asserted later[1] "The Louis XVI style formed in shape and structure the end of late baroque tendencies, with classicism serving as its framework." In the sense that neoclassicism in architecture is evocative and picturesque, a recreation of a distant, lost world, it is, as Giedion suggests, framed within the Romantic sensibility. Intellectually Neoclassicism was symptomatic of a desire to return to the perceived "purity" of the arts of Rome, the more vague perception ("ideal") of Ancient Greek arts and, to a lesser extent, sixteenth-century Renaissance Classicism, the source for academic Late Baroque. Many neoclassical architects were influenced by the drawings and projects of Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude Nicolas Ledoux. The many graphite drawings of Boullée and his students depict architecture that emulates the eternality of the universe. There are links between Boullée's ideas and Edmund Burke's conception of the sublime. Pulteney Bridge, Bath, England, by Robert Adam Ledoux addressed the concept of architectural character, maintaining that a building should immediately communicate its function to the viewer. -

Architecture & Design

TIMELESS BEAUTY, PROPORTION AND VISION IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF ITALY’S MOST INFLUENTIAL ARCHITECT He had an unquenchable passion that inspired him to great achievements – and many others over the centuries would emulate his Palladian principles. Today, a unique embodiment of the renowned architect’s vision, a masterpiece unlike any other in America, stands in Newport Beach. PALLADIO’S LEGACY Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), the acclaimed architect of the High Renaissance and arguably Italy’s most influential architect ever, is celebrated for his churches, villas, palaces and other grand edifices in Northern Italy. Internationally heralded over the centuries, his architectural style – based on the classic building principles of ancient Rome and Greece – emphasizes perfect harmony with the natural landscape. While the modern-day concept of a resort property was unknown in Palladio’s day, the grand master would be impressed by the inspired adaptation of his Palladian style at The Resort at Pelican Hill®. Crisp lines, elegant proportions, classically-designed porticos, beauty combined with functionality, new yet timeless, residential yet grand – these are descriptions of Palladio’s work, shared by Pelican Hill. Appropriately, the Resort opened November 26, 2008 – virtually 500 years to the day of the birth in 1508 of Palladio. Palladio was only a youth when he dedicated himself to the study of architecture, becoming a disciple of Vitruvius, the first century-BC writer who chronicled Roman architecture and conducted continuous empirical research at ancient architectural sites. Palladio came to believe that the ancient Greeks and Romans had found a perfect union of geometry, measure and proportion in their architecture – qualities - more - Pelican Hill Architecture Page 2 and characteristics that mirrored the beauty found in nature and the human body. -

HAMMOND-HARWOOD HOUSE ARCHITECTURAL TOUR Prepared by Sarah Benson March 2008

HAMMOND-HARWOOD HOUSE ARCHITECTURAL TOUR Prepared by Sarah Benson March 2008 Major themes: their interests. Don’t be intimidated if * materials and methods of house building visitors know more about colonial * the status of the architect in colonial architecture than you do or if they are America themselves architects. Invite them to * the forms and meanings of Anglo- bring their expertise to bear on the tour. Palladian architecture in America and the power of the classical tradition Order of the tour: Gallery The tour materials include: EXTERIOR Narrative script p. 2 Maryland Avenue façade Outline version p. 30 Garden façade Important characters p. 37 SERVICE AREAS Glossary p. 37 Basement Bibliography p. 39 Kitchen FIRST FLOOR The narrative script will give you a full Best Bedchamber background for the tour, while the outline Study emphasizes the key points. Draw on the Passage narrative and your own experiences in Dining Room leading tours of the house to flesh out the Parlour outline. A bibliography directs you to Stair Passage further reading if there are topics you SECOND FLOOR wish to explore in greater depth. Stair Passage Study Chamber Your audience is likely to include people Upper Passage with a range of knowledge about colonial Northeast Chamber architecture. Visitors may or may not Gaming Room have heard of Andrea Palladio and may or Ballroom / Withdrawing Room may not have visited other colonial houses in the region. Draw them out to discover NARRATIVE SCRIPT INTRODUCTION GALLERY The house was begun in 1774 for MATTHIAS HAMMOND, a wealthy planter who also served in the Maryland state legislature. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

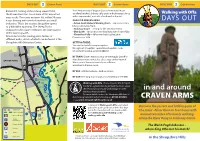

In and Around CRAVEN ARMS

River Onny Railway Station Bus DAYS OUT 2 Craven Arms B4368 DAYS OUT 2 Craven Arms DAYS OUT 2 Craven Arms CRAVEN ARMS Stop Before theBus coming of the railway around 1853, You’ll find an array of shops in Craven Arms including an the CravenStop Arms Inn stood alone at this important excellent butcher’s, bakery, cafes, pubs and takeaways, along Walking with Offa Land of with a supermarket, post office, bank and cash point. cross-roads. There wasLost no Contenttown. Yet within 50 years B4368 it was thriving with Marketlivestock St markets and small CLOSE TO CRAVEN ARMS DAYS OUT industries. This is the nearest Shropshire comes • Acton Scott Historic Working Farm – experience daily to a Wild West township.Newton The Sheep Tracks life on a Victorian Farm sculpture in the square celebrates the twin sources • Stokesay Court – setting for the film Atonement • Clun Castle – explore these medieval ruins at the heart of Clun of the town’s growth. • Flounders Folly – 80ft tower built by Benjamin Craven Arms is the starting pointShropshire for lots Hills of Flounders in 1838 different walks, details of whichDiscovery can Centrebe found at the Shropshire Hills Discovery Centre. GETTING THERE: You can find public transport options Onny MeadowRiver Onny throughout Shropshire - www.traveshropshire.co.uk. Or contact Traveline on 08712 002233. Railway Station BY TRAIN: Craven Arms is a stop on the regular Cardiff to Bus B4368 CRAVEN ARMS Stop Manchester train service. It is also a stop on the Heart of Bus A49 Wales, one of the most scenic lines in Britain, Stop Land of www.heart-of-wales.co.uk. -

18Th Century: Archaeological Discoveries and the Emergence of Historicism

18th Century: Archaeological discoveries and the emergence of historicism Rediscovery of the Temple of Isis at Pompeii (1765) Pietro Fabris -During the 18th century, Rome was still the center of cultural interchange (throughout the most productive phases of neo- classicism) in its richness of the antique ruins. -However, many new archaeological discoveries in different parts of Europe enabled architects to review the remains of classical architecture without visiting and staying extensively in Rome. -These archaeological discoveries revealed the fragments of the Greek and Roman cultures. -These fragments were now observable in an increasing number and range throughout the Mediterranean and the Near East. -These discoveries led the antiquities of the Greek and Roman cultures to be perceived widely beyond Greece and Italy. -There was an attitude of studying the antiquities with a renewed passion, because in one’s own town was an excellent remains of the classical culture. Emergence of Historicism -Interestingly, the 18th century was also the period in which an awareness of the plurality of architectural styles was first felt. -There were not only the classical architecture. -Architects now saw other styles of architecture: Egyptian, Islamic, Gothic, and even Chinese. Chinese Pavillion (after 1778) Val d’oise Cassan, France Recueil, title page survey of the history of architecture according to function (1800) J.N.L. Durand (1760-1834) Historicism -This cultural atmosphere gave rise to a unique attitude of history, which was called historicism, a degraded notion of history. -Historicism is an attitude in which one sees history with the lens of multiple styles to select -History appears as the inventory of available styles in which there was no reason to consider one style superior to another.