Governance and Locality in the Age of Reform: Birmingham, 1769-1852

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

The Opaque Nature of John Constable's Naturalism

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 12:44 RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review The Opaque Nature of John Constable’s Naturalism Iris Wien The Nature of Naturalism : A Trans-Historical Examination Résumé de l'article La nature du naturalisme : un examen transhistorique Situant les dessins de Constable dans un contexte épistémologique Volume 41, numéro 2, 2016 post-Berkleyien, cet article suggère que le basculement vers une structure représentationnelle, qui met l’accent sur l’écart entre les fonctions figuratives URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1038071ar et picturales, avait été nécessaire pour assurer la prétention à la vérité du DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1038071ar naturalisme de l’artiste. Nous soutenons que les modulations réalistes dans la conceptualisation sémiotique de Berkeley de la perception visuelle furent instrumentales à une esthétique qui s’efforçait d’enligner le langage de la Aller au sommaire du numéro nature avec le sentiment, réconciliant ainsi l’expression subjective et les demandes de l’objectivité. Pourtant, ainsi que nous le démontrons, la rupture d’un ordre de représentation « transparent » qu’opéra Constable eut des Éditeur(s) implications non seulement scientifiques, mais également idéologiques. UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (imprimé) 1918-4778 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Wien, I. (2016). The Opaque Nature of John Constable’s Naturalism. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 41(2), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038071ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Birmingham Museums Supplement

BIRMINGHAM: ITS PEOPLE, ITS HISTORY Birmingham MUSEUMS Published by History West Midlands www.historywm.com fter six years of REVEALING BIRMINGHAM’S HIDDEN HERITAGE development and a total investment of BIRMINGHAM: ITS PEOPLE, ITS HISTORY A £8.9 million, The new ‘Birmingham: its people, its history’ galleries at Birmingham Museum & Art ‘Birmingham: its people, its Gallery, officially opened in October 2012 by the Birmingham poet Benjamin history’ is Birmingham Museum Zephaniah, are a fascinating destination for anyone interested in history. They offer an & Art Gallery’s biggest and most insight into the development of Birmingham from its origin as a medieval market town ambitious development project in through to its establishment as the workshop of the world. But the personal stories, recent decades. It has seen the development of industry and campaigns for human rights represented in the displays restoration of large parts of the have a significance and resonance far beyond the local; they highlight the pivotal role Museum’s Grade II* listed the city played in shaping our modern world. From medieval metalwork to parts for building, and the creation of a the Hadron Collider, these galleries provide access to hundreds of artefacts, many of major permanent exhibition which have never been on public display before. They are well worth a visit whether about the history of Birmingham from its origins to the present day. you are from Birmingham or not. ‘Birmingham: its people, its The permanent exhibition in the galleries contains five distinct display areas: history’ draws upon the city’s rich l ‘Origins’ (up to 1700) – see page 1 and nationally important l ‘A Stranger’s Guide’ (1700 to 1830) – see page 2 collections to bring Birmingham’s l ‘Forward’ (1830 to 1909) – see page 3 history to life. -

Some Pages from the Book

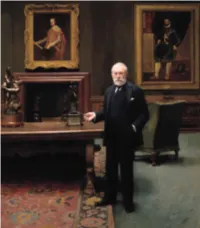

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Introduction

How did Britain Democratize? Views from the Sovereign Bond Market Aditya Dasgupta1 Daniel Ziblatt2 Abstract To assess competing theories of democratization, we analyze British sovereign bond market responses to the 1832, 1867 and 1884 Reform Acts, and to two failed Chartist agitations. Analyses of high-frequency 3% consol yield data and historical financial press suggest three conclusions. First, democratic reform episodes were preceded by increases in perceived political risk, comparable to democratizing episodes in other countries. Second, both democratic reform and repression were followed by yield de- clines. Third, the source of political risk in Britain was both social unrest and political deadlock. Together, the findings challenge the \Whig" characterization of British de- mocratization as exceptionally risk-free. Introduction The process of democratization in Britain { the franchise expansions legislated in the 1832, 1867, and 1884 Reform Acts in particular { has attracted a great deal of scholarly argument over how democracy emerged. One long-standing view, rooted in a classical \Whig" interpre- tation of history (see critique by Herbert Butterfield (1965)), is that Britain was distinctive in requiring little social and political conflict to democratize. Others argue that, whether driven by destabilizing constitutional crises or even the threat of mass revolution (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2005), the process of democratization in Britain was deeply conflictual. A key empirical issue at stake in this debate is this: what was the level of perceived political risk during each of Britain's major episodes of suffrage expansion? Scholars on both sides of 1PhD Candidate, Department of Government, Harvard University. Email: [email protected] 2Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University. -

New Men of Wealth and the Purchase of Land in Great Britain and Ireland, 1780 to 1879*

New men of wealth and the purchase of land in Great Britain and Ireland, 1780 to 1879* new men of wealth by David Brown Abstract Of all the indicators of the integration of the bourgeoisie class and the aristocracy, the most important was the purchase of a residence and a landed estate by ‘new men of wealth’. In new research, 2566 new men of wealth have been identified who purchased estates of over 1000 acres and a rental of £1000 in Great Britain and Ireland between 1780 and 1879. Of those, 1439 purchased estates of over 2000 acres in extent and £2000 in rental, which represents an estimated turnover of over 38 per cent over the century. Although there is no consensus about what level of upward mobility is required for an elite to be ‘open’, these figures demonstrates that there were sufficient purchasers to sustain the contemporary belief that Britain’s elite was indeed open. The relationship between plutocratic and aristocratic elites in the century of the classic Industrial Revolution has been a topic of great interest to historians. For example, Avner Offer has explored the development of the ideology of a ‘free trade in land’ to break the aristocratic dominance achieved through the use of strict settlement. R. J. Morris has considered the strategies adopted by middle-class families to succeed in a period where landed wealth still dominated.1 The most divisive, and arguably the key issue about this relationship, arising from the Marxist model of conflict between the rising bourgeois elite and the declining aristocratic elite, has been the tendency of ‘new wealth’ to join the ranks of landowners. -

HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain | University of Stirling

10/01/21 HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain | University of Stirling HIS9F6: Protests, Riots and Propaganda: View Online Popular Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain E V Macleod Aspinall, A. (1949) Politics and the press, c.1780-1850. Home and Van Thal. Barker, H. (1996) ‘Catering for Provisional Tastes: Newspapers, Readership and Profit in Late Eighteenth-Century England’, Historical Research, 69(168), pp. 42–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.1996.tb01841.x. Barker, H. (2000) ‘Growth of newspapers, IN: Newspapers, politics and English society 1695-1855’, in Newspapers, politics and English society, 1695-1855. Harlow: Longman, pp. 29–45. Barker, Hannah and Chalus, Elaine (1997) Gender in eighteenth-century England: roles, representations and responsibilities. London: Longman. Bennett, Betty T. (1976) British war poetry in the age of romanticism, 1793-1815. New York: Garland Pub. Bindman, D. (1999) ‘Prints’, in An Oxford companion to the Romantic age: British culture, 1776-1832. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 207–213. Bob Harris (1995) ‘The London Evening Post and Mid-Eighteenth-Century British Politics’, The English Historical Review, 110(439), pp. 1132–1156. Available at: http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.stir.ac.uk/stable/577253. Bohstedt, J. (1988) ‘GENDER, HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY POLITICS: WOMEN IN ENGLISH RIOTS 1790–1810’, Past and Present, 120(1), pp. 88–122. doi: 10.1093/past/120.1.88. Booth, A. (1977a) ‘FOOD RIOTS IN THE NORTH–WEST OF ENGLAND 1790–1801’, Past and Present, 77(1), pp. 84–107. doi: 10.1093/past/77.1.84. Booth, A. (1977b) ‘FOOD RIOTS IN THE NORTH–WEST OF ENGLAND 1790–1801’, Past and Present, 77(1), pp. -

“FRESHER by FAR” PRODUCE Ple of Peace with Israel and .Ac Son of West Hartfrod

.r • 'V*- r \ .. ^ \ V I • P A G E F O R T Y WEDNESDAY, 'JUNE 24, 1970 ittanrliratpr lEaatttng H^araUt A :\ Jfosf Manchester Stores Open Until 9 O^Clock Members of Scandla Lodge, About Town Vasa Order of America, will at Some Downtown Shoppers Average Daily Net Prem Run r h , Parents Without Partners, tend Vasa Field Day on Sun The Weather Manchester Chapter, will hold day starting at 9:80 a.m. at AN EXOmm PARTY IDGAI For The Week Kkided Vasa Park, South Meriden. To Receive Lucky Bucks June 99, 1970 Fair, unsenaonably oqdI an Informal coffee and conver CiMfemar flefc-Up nigtit; low about SS. Ttamorroav sation, at the home of Mrs. Ed There will be entertainment, games and dancing. Dinners sunny, low humkUity; Mgh na Geer, 80 W'etherell St. to “ Lucky Buck" cards will be tion was the Mystery Shopper. Hem* D«1lv«r*d liH M * of Swedish meatballs and sill distributed to shoppers in the 70a. Saturday’s ouUook-«taudy, night at 8. The meeting is open Next month, the promotion 15,770 herring wlU be served. Hoidogs Downtown business area tomor chance o< alwwrara. to interested persons. Hostess wilt focus on the mid-July Side in tmd hamburgers will alsO' be row through Saturday, entitling walk Sales. In August, actual- Mancheater— A City of Village Charm asks, to be notified by those available. the card holders to $6 worth of size antique cars will be dis planning to attend. retail merchandising. played in the Downtown busi i move VOL. LXXXIX, NO. -

Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election by Andrew Edward Reekes A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Research School of History and Cultures University of Birmingham March 2014 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1906 General Election marked the end of a prolonged period of Unionist government. The Liberal Party inflicted the heaviest defeat on its opponents in a century. Explanations for, and the implications of, these national results have been exhaustively debated. One area stood apart, Birmingham and its hinterland, for here the Unionists preserved their monopoly of power. This thesis seeks to explain that extraordinary immunity from a country-wide Unionist malaise. It assesses the elements which for long had set Birmingham apart, and goes on to examine the contribution of its most famous son, Joseph Chamberlain; it seeks to establish the nature of the symbiotic relationship between them, and to understand how a unique local electoral bastion came to be built in this part of the West Midlands, a fortress of a durability and impregnability without parallel in modern British political history. -

In England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530

Victoria Shirley The Galfridian Tradition(s) in England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Cardiff University 2017 i Abstract This thesis examines the responses to and rewritings of the Historia regum Britanniae in England, Scotland, and Wales between 1138 and 1530, and argues that the continued production of the text was directly related to the erasure of its author, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In contrast to earlier studies, which focus on single national or linguistic traditions, this thesis analyses different translations and adaptations of the Historia in a comparative methodology that demonstrates the connections, contrasts and continuities between the various national traditions. Chapter One assesses Geoffrey’s reputation and the critical reception of the Historia between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, arguing that the text came to be regarded as an authoritative account of British history at the same time as its author’s credibility was challenged. Chapter Two analyses how Geoffrey’s genealogical model of British history came to be rewritten as it was resituated within different narratives of English, Scottish, and Welsh history. Chapter Three demonstrates how the Historia’s description of the island Britain was adapted by later writers to construct geographical landscapes that emphasised the disunity of the island and subverted Geoffrey’s vision of insular unity. Chapter Four identifies how the letters between Britain and Rome in the Historia use argumentative rhetoric, myths of descent, and the discourse of freedom to establish the importance of political, national, or geographical independence. Chapter Five analyses how the relationships between the Arthur and his immediate kin group were used to challenge Geoffrey’s narrative of British history and emphasise problems of legitimacy, inheritance, and succession. -

The Development of Provided Schooling for Working Class Children

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROVIDED SCHOOLING FOR WORKING CIASS CHILDREN IN BIRMINGHAM 1781-1851 Michael Brian Frost Submitted for the degree of Laster of Letters School of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Birmingham, 1978. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis considers the development of 'provided 1 schooling for working class children in Birmingham between 1781 and 1851. The opening chapters critically examine the available statistical evidence for schooling provision in this period, suggesting how the standard statistical information may be augmented, and then presenting a detailed chronology of schooling provision and use. The third chapter is a detailed survey of the men who were controlling and organizing schooling during the period in question. This survey has been made in order that a more informed examination of the trends in schooling shown by the chronology may be attempted. The period 1781-1851 is divided into three roughly equal periods, each of which parallels a major initiative in working class schooling; 1781-1804 and the growth of Sunday schools, 1805-1828 and the development of mass day schooling through monitorial schools, and 1829- 1851 and the major expansion of day schooling. -

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional