Download Entire Virginia Saltwater Angler's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1978. Nota Sobre Los Primeros Resultados De La Campaña De Marcado De Túnidos Frente Al Litoral De Castellón

110 Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1978. Nota sobre los primeros resultados de la campaña de marcado de túnidos frente al litoral de Castellón. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 4 (3): 140–142 Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1981. Contribution à la connaissance de la migration des Scombridae en Méditerranée Occidentale. Rapp. P-V, Commn. Int. Explor. Scient. Mer Méditerr., 27: 97–98. Rey, J.C., Alot, E. and Ramos, A. 1984. Sinopsis biológica del bonito, Sarda sarda (Bloch), del Mediterráneo y Atlántico Este. Iccat, Coll. Vol. Sci. Pap. 20(2): 469–502. Rey, J.C., Alot, E. and Ramos, A. 1986. Growth of the Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda Bloch, 1793) in the Atlantic and Mediterranean area of the Strait of Gibraltar. Inv. Pesq. 50 (2): 179–185. Robert, M. and Roesti. 1966. The Declining Economic Role of the Mediterranean Tuna Fishery American Journal of Economics and Sociology 25 (1), 77–90. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1966. Estudio de la bacoreta, Euthynnus alleteratus (Raf.) bonito, Sarda sarda (Bloch) y melva, Auxis thazard (Lac.), capturados por las almadrabas españolas. Inv. Pesq. 30: 247–292. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1981. Estudio de la edad y crecimiento del bonito, Sarda sarda (Block), de la costa sudatlantica de España. Inv. Pesq. 45(1):181–186. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1983. Edad y crecimiento de la melva, Auxis rochei (Risso), del Sur de España. Invest. Pesq. (Barc.), 47 (3): 397–402. Sabatés, A. and Recasens, L. 2001. Seasonal distribution and spawning of small tunas, Auxis rochei (Risso) and Sarda sarda (Bloch) in the northwestern Mediterranean. -

Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2017 Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E. Hepner University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Other Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hepner, Megan E., "Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by Megan E. Hepner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Marine Science with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Frank Muller-Karger, Ph.D. Christopher Stallings, Ph.D. Steve Gittings, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 31st, 2017 Keywords: Species richness, biodiversity, functional diversity, species traits Copyright © 2017, Megan E. Hepner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to my major advisor, Dr. Frank Muller-Karger, who provided opportunities for me to strengthen my skills as a researcher on research cruises, dive surveys, and in the laboratory, and as a communicator through oral and presentations at conferences, and for encouraging my participation as a full team member in various meetings of the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) and other science meetings. -

Forage Fishes of the Southeastern Bering Sea Conference Proceedings

a OCS Study MMS 87-0017 Forage Fishes of the Southeastern Bering Sea Conference Proceedings 1-1 July 1987 Minerals Management Service Alaska OCS Region OCS Study MMS 87-0017 FORAGE FISHES OF THE SOUTHEASTERN BERING SEA Proceedings of a Conference 4-5 November 1986 Anchorage Hilton Hotel Anchorage, Alaska Prepared f br: U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service Alaska OCS Region 949 East 36th Avenue, Room 110 Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4302 Under Contract No. 14-12-0001-30297 Logistical Support and Report Preparation By: MBC Applied Environmental Sciences 947 Newhall Street Costa Mesa, California 92627 July 1987 CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................. iv INTRODUCTION PAPERS Dynamics of the Southeastern Bering Sea Oceanographic Environment - H. Joseph Niebauer .................................. The Bering Sea Ecosystem as a Predation Controlled System - Taivo Laevastu .... Marine Mammals and Forage Fishes in the Southeastern Bering Sea - Kathryn J. Frost and Lloyd Lowry. ............................. Trophic Interactions Between Forage Fish and Seabirds in the Southeastern Bering Sea - Gerald A. Sanger ............................ Demersal Fish Predators of Pelagic Forage Fishes in the Southeastern Bering Sea - M. James Allen ................................ Dynamics of Coastal Salmon in the Southeastern Bering Sea - Donald E. Rogers . Forage Fish Use of Inshore Habitats North of the Alaska Peninsula - Jonathan P. Houghton ................................. Forage Fishes in the Shallow Waters of the North- leut ti an Shelf - Peter Craig ... Population Dynamics of Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii), Capelin (Mallotus villosus), and Other Coastal Pelagic Fishes in the Eastern Bering Sea - Vidar G. Wespestad The History of Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) Fisheries in Alaska - Fritz Funk . Environmental-Dependent Stock-Recruitment Models for Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) - Max Stocker. -

Melges 17 - Affordable for Those Looking to Get More Involved Any Member Who Would Like More Infor- Inshore Fun in Our Various Sailing Programs in 2017, Mation

January - February 2017 www.mbyc.com Winter Fun MACATAWA BAY YACHT CLUB • 2157 SOUTH SHORE DRIVE • MACATAWA, MI 49434 • 616-335-5815 Flag Report Lisa Ruoff Tom Sligh Rod Schmidt Commodore Vice Commodore Rear Commodore Happy New Year! The Holiday Party and New Year’s Eve ed the Club could not support an infinite number of racing Party are now memories. Thank you for attending them and fleets. A large portion of this issue is geared toward our newly sharing in the celebration. The amazing Social Committee approved racing fleets. These are not necessarily new fleets, deserves kudos for the fabulous décor indoors and out. but they have been recognized as supportable with the volun- teer resources at our disposal. If you’ve had questions about The next time you come to the Club you may notice some racing, your questions may be answered in these articles from much-needed repairs for which Julie had budgeted. Jack each fleet. If not, you will find contact information for each Walker will report more information on that in a future Wind fleet. Scoop issue. One advantage of the Club being closed during January, February and half of March is that our hardwork- Finally, thank you to the more than 300 of you who respond- ing staff gets a bit of a break and some of the deep cleaning ed to the Member Survey. That data will be analyzed and will and maintenance can be tackled. When the Club opens in help the Board make your Club experience the best it can mid-March not only will everything be sparkling clean, we be. -

2020 Journal

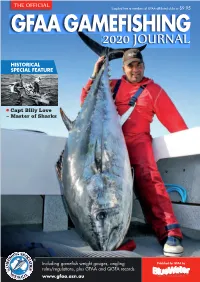

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Conservation and Ecology of Marine Forage Fishes— Proceedings of a Research Symposium, September 2012

Conservation and Ecology of Marine Forage Fishes— Proceedings of a Research Symposium, September 2012 Open-File Report 2013–1035 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Upper Left: Herring spawn, BC coast – Milton Love, “Certainly More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast,” reproduced with permission. Left Center: Tufted Puffin and sand lance (Smith Island, Puget Sound) – Joseph Gaydos, SeaDoc Society. Right Center: Symposium attendants – Tami Pokorny, Jefferson County Water Resources. Upper Right: Buried sand lance – Milton Love, “Certainly More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast,” reproduced with permission. Background: Pacific sardine, CA coast – Milton Love, “Certainly More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast,” reproduced with permission. Conservation and Ecology of Marine Forage Fishes— Proceedings of a Research Symposium, September 2012 Edited by Theresa Liedtke, U.S. Geological Survey; Caroline Gibson, Northwest Straits Commission; Dayv Lowry, Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife; and Duane Fagergren, Puget Sound Partnership Open-File Report 2013–1035 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2013 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Liedtke, Theresa, Gibson, Caroline, Lowry, Dayv, and Fagergren, Duane, eds., 2013, Conservation and Ecology of Marine Forage Fishes—Proceedings of a Research Symposium, September 2012: U.S. -

Appendix A. Navy Activity Descriptions

Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 APPENDIX A Navy Activity Descriptions Appendix A Navy Activity Descriptions Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 This page intentionally left blank. Appendix A Navy Activity Descriptions Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing TABLE OF CONTENTS A. NAVY ACTIVITY DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................................ A-1 A.1 Description of Sonar, Munitions, Targets, and Other Systems Employed in Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Events .................................................................. A-1 A.1.1 Sonar Systems and Other Acoustic Sources ......................................................... A-1 A.1.2 Munitions .............................................................................................................. A-7 A.1.3 Targets ................................................................................................................ A-11 A.1.4 Defensive Countermeasures ............................................................................... A-13 A.1.5 Mine Warfare Systems ........................................................................................ A-13 A.1.6 Military Expended Materials ............................................................................... A-16 A.2 Training Activities .................................................................................................. -

How Transient Patches Affect Population Dynamics: the Case of Hypoxia and Blue Crabs

Ecological Monographs, 76(3), 2006, pp. 415–438 Ó 2006 by the Ecological Society of America HOW TRANSIENT PATCHES AFFECT POPULATION DYNAMICS: THE CASE OF HYPOXIA AND BLUE CRABS 1,3 2 1 CRAIG A. AUMANN, LISA A. EBY, AND WILLIAM F. FAGAN 1Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 USA 2Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812 USA Abstract. Transient low-oxygen patches may have important consequences for the population dynamics of estuarine species. We investigated whether these transient hypoxic patches altered population dynamics of the commercially important blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) and assessed two alternative hypotheses for the causal mechanism. One hypothesis is that temporary reductions in habitat due to hypoxia increase cannibalism. The second hypothesis is that crab population dynamics result from food limitation caused by hypoxia- induced mortality of the benthos. We developed a spatially explicit individual-based model of blue crabs in a hierarchical framework to connect the autoecology of crabs with the spatial and temporal dynamics of their physical and biological environments. Three primary scenarios were run to examine the interactive effects of (1) hypoxic extent vs. static and transient patches, (2) hypoxic extent vs. prey abundance, and (3) hypoxic extent vs. cannibalism potential. Static patches resulted in populations limited by egg production and recruitment whereas transient patches led to populations limited by the effects of cannibalism and patch interactions. Crab survivorship was greatest for simulations with the largest hypoxic patches which also had the lowest prey abundance and lowest crab densities. In these simulations, nearly all crab mortality was accounted for by aggression, not starvation. -

Sharkcam Fishes

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2020. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 201 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 5.0. 24 February 2020. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index TABLE OF CONTENTS SILVERY FISHES (23) ........................... 47 African Pompano ......................................... 48 FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION .............. 6 Crevalle Jack ................................................. 49 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES ...................... 10 Permit .......................................................... 50 Sharks and Rays ........................................ 10 Almaco Jack ................................................. 51 Illustrations of SharkCam -

Fishing the Red River of the North

FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH The Red River boasts more than 70 species of fish. Channel catfish in the Red River can attain weights of more than 30 pounds, walleye as big as 13 pounds, and northern pike can grow as long as 45 inches. Includes access maps, fishing tips, local tourism contacts and more. TABLE OF CONTENTS YOUR GUIDE TO FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH 3 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT 4 RIVER STEWARDSHIP 4 FISH OF THE RED RIVER 5 PUBLIC ACCESS MAP 6 PUBLIC ACCESS CHART 7 AREA MAPS 8 FISHING THE RED 9 TIP AND RAP 9 EATING FISH FROM THE RED RIVER 11 CATCH-AND-RELEASE 11 FISH RECIPES 11 LOCAL TOURISM CONTACTS 12 BE AWARE OF THE DANGERS OF DAMS 12 ©2017, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources FAW-471-17 The Minnesota DNR prohibits discrimination in its programs and services based on race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, public assistance status, age, sexual orientation or disability. Persons with disabilities may request reasonable modifications to access or participate in DNR programs and services by contacting the DNR ADA Title II Coordinator at [email protected] or 651-259-5488. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to Minnesota DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4049; or Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C. Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. This brochure was produced by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife with technical assistance provided by the North Dakota Department of Game and Fish. -

July 2001 FBYC Web Site

July 2001 FBYC Web Site: http://www.FBYC.net Junior Week as 16 year olds.” After the From the Quarterdeck by Strother Scott, Commodore Leukemia Cup, from C.T. Hill, CEO of One of the joys of being your Compliments I received included – our lead sponsor – “I am very happy we commodore has been being at Club for “My kid just finished the Opti-kid at SunTrust chose to become a sponsor the last 10 days and watching in program – Jan Monnier does a really of your event. This is a good event for a wonder as the Club conducts large and great job with those children – we’ll good cause with good people. SunTrust complex functions and executes them be back again.” After Junior Week is proud to be associated with it.” perfectly. We have just concluded 2 from a member – “I want you to Our hopes are high for our traveling weekends of Opti-Kids (25 children), know that this year’s Junior Week Juniors. Our Coaches, Blake the biggest and best Junior Week ever was well run, the layout at the club Kimbrough (MRBYTEMAN@aol. held (110 students, 24 instructors and worked really well in spite of no com) and Anthony Kuppersmith 6 CITs), and the 2001 Southern Bay clubhouse. My wife and I and our ([email protected]) are ready and the Volvo Leukemia Cup (53 boats racing children have had a great time, it has calendar is set (see http://www.fbyc.net/ and over $80,000 raised). The turned out to be the best vacation Juniors/). -

Spp List.Xlsx

Common name Scientific name ANGIOSPERMS Seagrass Halodule wrightii Manatee grass Syringodium filiforme Turtle grass Thalassia testudinium ALGAE PHAEOPHYTA Y Branched algae Dictyota sp Encrusting fan leaf algae Lobophora variegata White scroll algae Padina jamaicensis Sargassum Sargassum fluitans White vein sargassum Sargassum histrix Saucer leaf algae Turbinaria tricostata CHLOROPHYTA Green mermaid's wine glass Acetabularia calyculus Cactus tree algae Caulerpa cupressoides Green grape algae Caulerpa racemosa Green bubble algae Dictyosphaeria cavernosa Large leaf watercress algae Halimeda discoidea Small-leaf hanging vine Halimeda goreaui Three finger leaf algae Halimeda incrassata Watercress algae Halimeda opuntia Stalked lettuce leaf algae Halimeda tuna Bristle ball brush Penicillus dumetosus Flat top bristle brush Penicillus pyriformes Pinecone algae Rhipocephalus phoenix Mermaid's fans Udotea sp Elongated sea pearls Valonia macrophysa Sea pearl Ventricaria ventricosa RHODOPHYTA Spiny algae Acanthophora spicifera No common name Ceramium nitens Crustose coralline algae Corallina sp. Tubular thicket algae Galaxaura sp No common name Laurencia obtusa INVERTEBRATES PORIFERA Scattered pore rope sponge Aplysina fulva Branching vase sponge Callyspongia vaginalis Red boring sponge Cliona delitrix Brown variable sponge Cliona varians Loggerhead sponge Spheciospongia vesparium Fire sponge Tedania ignis Giant barrel sponge Xestospongia muta CNIDARIA Class Scyphozoa Sea wasp Carybdea alata Upsidedown jelly Cassiopeia frondosa Class Hydrozoa Branching