Does the Wheel Come Full Circle in Former Yugoslavia?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queens of the Stone Age 9

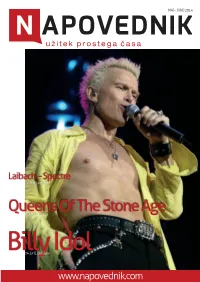

MAJ – JUNIJ 2014 Laibach – Spectre 16. maj, Ljubljana Queens Of The Stone Age 9. junij, Ljubljana Billy24. junij, Ljubljana Idol www.napovednik.com KAZALO 04 Ali že veste? 28 Prireditve Skuhna 06 Glasba 28 Skuhna – svetovna kuhinja po slovensko. Laibach Spectre ARTish 06 Preroki teme in apostoli noči v Križankah! 31 Prodajno-razstavni umetniški festival. Željko Bebek & Bend 06 Koncert v Cvetličarni ob 40-letnici delovanja. 32 Delavnice The Rolling Stones 07 Obisk treh koncertov organizirajo Koncerti.net. 36 Za otroke Queens of the Stone Age Mali raziskovalci morja 10 Po več kot desetih letih se vračajo v Ljubljano! 36 Raziskovalna avantura za otroke, stare od 6 do 12 let. Darko Brlek: Manj denarja, več muzike Družinski center Mala ulica 11 Intervju s prvim možem Festivala Ljubljana. 37 Javna dnevna soba za starše in otroke. 38 Kino Billy Idol 12 Slavni glasbenik junija prihaja v Halo Tivoli. Bajaga & Instruktori z gosti Komedija Sosedi 13 Veliki koncert ob 30-letnici legendarne skupine. 38 V kinematografih Cinneplexx bo teden dni pred drugimi! Punca ni nič kriva 16 Gledališče 38 Kino Šiška in Kinodvor pripravljata pin-up večer. Zeleni Jurij Možje X: Dnevi prihodnje preteklosti 16 Muzikal po ljudskih motivih. 40 Nadaljevanje sage o konfliktu med ljudmi in mutanti. Festival Prelet Zlohotnica 19 Mladinsko in Glej: pester program kar 15-ih predstav. 40 Angelina Jolie v akcijsko pustolovski drami. The Umbilical Brothers 21 V Siti Teater BTC se vračata slavna komika. 42 Avenija Mrtvec pride po ljubico 22 Predstava Svetlane Makarovič v PGK. 44 Mljask Dva koraka do hitrejšega metabolizma 26 Razstave 44 Pred obrokom naredite dve stvari … Emona: mesto v imperiju Recept 26 Razstava ob 2000-letnici urbane poselitve Ljubljane. -

List Ženskoga Đačkoga Doma Split / Broj 24, Godina 2020

POLETLIST ŽENSKOGA ĐAČKOGA DOMA SPLIT / BROJ 24, GODINA 2020. 1 SADRŽAJ Impressum .........................................................................2 Sadržaj ...............................................................................2 POLET Uvodnik ........................................................................... 3 Osobna iskaznica ............................................................ 4 UREDNIŠTVO Ime je znak ....................................................................... 5 Učenice DOMSKI DANI Antonela Dominiković, Ivana Čepo, Od Poleta do Poleta ...........................................................6 Issa Ćudina, Barbara Parunov, Gdje smo bili, što smo radili? ..........................................7 Dora Pašalić, Mija Sabljić, Anita Vudrag Blizanke u Ženskom đačkom domu ...................................11 Mentorica Činjenice i zanimljivosti o blizancima ...............................14 Đurđica Kamenjarin, prof. Brother from another mother ..............................................16 SURADNICE Fizička sličnost, slučajnost ili … ........................................16 Učenice VEZE Lea Ćelić, Mirela Dragojević, Obiteljske veze .................................................................17 Cecilija Jedretić, Morena Jerković, Rodbinske veze ................................................................19 Matija Knezović, Josipa Lozančić, Vršnjačke veze ..................................................................19 Ivana Lozančić, Natali Mikulandra, Veze u lektirnim djelima -

Acta Histriae

ACTA HISTRIAE ACTA ACTA HISTRIAE 23, 2015, 4 23, 2015, 4 ISSN 1318-0185 Cena: 11,00 EUR UDK/UDC 94(05) ACTA HISTRIAE 23, 2015, 4, pp. 591-822 ISSN 1318-0185 ACTA HISTRIAE • 23 • 2015 • 4 ISSN 1318-0185 UDK/UDC 94(05) Letnik 23, leto 2015, številka 4 Odgovorni urednik/ Direttore responsabile/ Darko Darovec Editor in Chief: Uredniški odbor/ Gorazd Bajc, Furio Bianco (IT), Flavij Bonin, Dragica Čeč, Lovorka Comitato di redazione/ Čoralić (HR), Darko Darovec, Marco Fincardi (IT), Darko Friš, Aleksej Board of Editors: Kalc, Borut Klabjan, John Martin (USA), Robert Matijašić (HR), Darja Mihelič, Edward Muir (USA), Egon Pelikan, Luciano Pezzolo (IT), Jože Pirjevec, Claudio Povolo (IT), Vida Rožac Darovec, Andrej Studen, Marta Verginella, Salvator Žitko Urednik/Redattore/ Editor: Gorazd Bajc Prevodi/Traduzioni/ Translations: Petra Berlot (angl., it., slo) Lektorji/Supervisione/ Language Editor: Petra Berlot (angl., it., slo) Stavek/Composizione/ Typesetting: Grafis trade d.o.o. Izdajatelj/Editore/ Published by: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko / Società storica del Litorale© Sedež/Sede/Address: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko, SI-6000 Koper-Capodistria, Kreljeva 3 / Via Krelj 3, tel.: +386 5 6273-296; fax: +386 5 6273-296; e-mail: [email protected]; www.zdjp.si Tisk/Stampa/Print: Grafis trade d.o.o. Naklada/Tiratura/Copies: 300 izvodov/copie/copies Finančna podpora/ Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije / Slovenian Supporto finanziario/ Research Agency Financially supported by: Slika na naslovnici/ Foto di copertina/ Picture on the cover: Saint Christopher Cynocephalus, represented with a wolf's head. Russian lubok (cca. 1700). File:ChristopherLubok.jpg. From Wikimedia Commons. -

Muzicki Program

MUZIČKI PROGRAM 2018 MAIN STAGE SUBOTA .. NEDELJA .. ČETVRTAK .. PETAK .. SREDA .. O RAINMAKER LOLE & RADI : - : : - : BLUES BAND THE FILTERS : - : HURLEUR IRON MAIDEN TRIBUTE : - : AERODROM : - : : - : FRAJLE : - : VIVA VOPS : - : ĐORĐE DAVID : - : RIBLJA ČORBA : - : BAND X : - : NEVERNE BEBE : - : YU GRUPA : - : E-PLAY : - : PARTIBREJKERS : - : DR NELE KARAJLIĆ : - : KIKI I PILOTI : - : DEJAN PETROVIĆ : - : ORTHODOX CELTS : - : LOLLOBRIGIDA : - : SIX PACK INSPEKTOR BLAŽA : - : : - : GOBLINI : - : LET I KLJUNOVI : - : ISKAZ INNOVATION STAGE NEDELJA .. PETAK .. SUBOTA .. SREDA .. ČETVRTAK .. BEND IZNENAĐENJA : - : SUNSHINE : - : THE STRANGLERS : - : VAN GOGH : - : RÓISÍN MURPHY : - : : - : BAD COPY ALTERNATIVE STAGE by NEDELJA .. PETAK .. SUBOTA .. SREDA .. ČETVRTAK .. BUNT : BUNT : BUNT : : - : : - : ALEJA VELIKANA MESIS : - : SERGIO LOUNGER BUNT : SITZPINKER : - : BUNT : NE SANJA TIŠMA I MASA : - : ARCTICK MONKEYS : - : VIS LIMUNADA : - : TRIBUTE OLA ČUTURILO : - : VATRA : - : FRAMEWORK : - : NIK : - : GILE & MAGIC BUSH STRAY DOGG : - : ZONA B STRAIGHT MICKEY : - : RIMLJANI ITE DOMA : - : : - : & THE BOYZ VELIKI PREZIR : - : NEŽNI DALIBOR : - : PEČITELJI : - : EX REVOLVERI : - : METALLICA TRIBUTE : - : PO PERO DEFFORMERO : - : ŠANK : - : ZOSTER : - : OBOJENI PROGRAM : - : M.O.R.T. : - : : - : KKN : - : BOLESNA ŠTENAD : - : ĐORĐE MILJENOVIĆ : - : LETU ŠTUKE DEPECHE TRIBUTE BAND : - : NBG : - : * ORGANIZATOR ZADRŽAVA PRAVO IZMENE PROGRAMA MUZIČKI PROGRAM 2018 INNOVATION ALTERNATIVE MAIN STAGE BY STAGE STAGE : - : BUNT : SITZPINKER : -

Ponuda Za LIVE 30.12.2017

powered by BetO2 kickoff_time event_id sport competition_name home_name away_name 2017-12-30 09:00:00 1050635 BASKETBALL South Korea KBL KCC Egis Seoul Thunders 2017-12-30 09:00:00 1050636 BASKETBALL South Korea WKBL Woori Bank Hansae Women Bucheon Keb Hanabank Women 2017-12-30 09:30:00 1050637 BASKETBALL Australia WNBL Women Melbourne Boomers Women Dandenong Women 2017-12-30 11:00:00 1050638 BASKETBALL Turkey Super Ligi Sakarya Pinar Karsiyaka 2017-12-30 11:30:00 1050733 BASKETBALL Turkey TBL Bahcesehir Koleji Socar Petkimspor 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050639 BASKETBALL China WCBA Bayi Women Xinjiang Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050640 BASKETBALL China WCBA Guangdong Women Jiangsu Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050641 BASKETBALL China WCBA Liaoning Women Beijing Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050642 BASKETBALL China WCBA Shenyang Women Zhejiang Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050643 BASKETBALL China WCBA Shandong Women Shanxi Xing Rui Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050644 BASKETBALL China WCBA Shanghai Women Shaanxi Tianze Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050866 BASKETBALL China WCBA Sichuan Women Heilongjiang Women 2017-12-30 12:30:00 1050758 BASKETBALL Turkey TBL Bakirkoy Yalova Belediye 2017-12-30 12:35:00 1050647 BASKETBALL China CBA Sichuan Guangzhou 2017-12-30 12:35:00 1050648 BASKETBALL China CBA Qingdao Beikong 2017-12-30 12:35:00 1050649 BASKETBALL China CBA Zhejiang Chouzhou Bank Jiangsu Dragons 2017-12-30 13:00:00 1050645 BASKETBALL China CBA Xinjiang Shenzhen 2017-12-30 13:15:00 1050650 BASKETBALL Turkey Super Ligi Usak Eskisehir Basket 2017-12-30 14:00:00 -

Annual Report Letno Poročilo

Annual Report Letno poročilo 2020 InnoRenew CoE Renewable Materials and Healthy Environments Research and Innovation Centre of Excellence InnoRenew CoE Center odličnosti za raziskave in inovacije na področju obnovljivih materialov in zdravega bivanjskega okolja Annual Report Letno poročilo 2020 Mentored by the Fraunhofer Institute for Wood Research, Wilhelm-Klauditz-Institut WKI (Fraunhofer WKI) Mentorstvo: Inštitut Fraunhofer Wilhelm-Klauditz (Fraunhofer WKI) Funded by the European Commission under Horizon 2020, the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (H2020 WIDESPREAD-2-Teaming #739574), and investment funding from the Republic of Slovenia and the European Regional Development Fund. Financiranje: Okvirni program Evropske unije Obzorje 2020 (H2020 WIDESPREAD-2-Teaming: #739574) in Republika Slovenija. Financiranje naložb Republike Slovenije in Evropske unije v okviru Evropskega sklada za regionalni razvoj. Cover photo / Naslovna fotografija Faksawat Poohphajai, Anna Sandak, Jakub Sandak: A microscopic image of pine sapwood roughness Mikroskopski posnetek hrapavosti beljave borovine 20 Annual Report 4 5 Letno poročilo 20 Table of contents Kazalo Foreword from the director ..................................................................................... 6 Predgovor direktorice ............................................................................................. 7 Foreword from the deputy director .......................................................................... 8 Predgovor namestnika direktorice ......................................................................... -

1 En Petkovic

Scientific paper Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1967 to 20031 UDC 811.163.41’322 DOI 10.18485/infotheca.2019.19.1.1 Ljudmila Petkovi´c ABSTRACT: The paper analyses the pro- [email protected] cess of creation and processing of the Yu- University of Belgrade goslav rock song lyrics corpus from 1967 to Belgrade, Serbia 2003, from the theoretical and practical per- spective. The data have been obtained and XML-annotated using the Python program- ming language and the libraries lyricsmas- ter/yattag. The corpus has been preprocessed and basic statistical data have been gener- ated by the XSL transformation. The diacritic restoration has been carried out in the Slovo Majstor and LeXimir tools (the latter appli- cation has also been used for generating the frequency analysis). The extraction of socio- cultural topics has been performed using the Unitex software, whereas the prevailing top- ics have been visualised with the TreeCloud software. KEYWORDS: corpus linguistics, Yugoslav rock and roll, web scraping, natural language processing, text mining. PAPER SUBMITTED: 15 April 2019 PAPER ACCEPTED: 19 June 2019 1 This paper originates from the author’s Master’s thesis “Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1945 to 2003”, which was defended at the University of Belgrade on March 18, 2019. The thesis was conducted under the supervision of the Prof. Dr Ranka Stankovi´c,who contributed to the topic’s formulation, with the remark that the year of 1945 was replaced by the year of 1967 in this paper. -

Poznati Učesnici Festivala "Omladina" Koji Će Biti Održan 07. I 08. Decembra

Poznati u česnici Festivala "Omladina" koji će biti održan 07. i 08. decembra Postavljeno: 21.10.2012 Posle dve decenije pauze i prošlogodišnje retrospektive jednog od najpopularnijih muzi čkih omladinskih festivala u bivšoj Jugoslaviji, Festival "Omladina" Subotica od ove godine će ponovo organizovati muzi čko takmi čenje i okupiti mlade autore iz nekoliko zemalja regiona. Festival će biti održan 07. i 08. decembra pod sloganom "Razli čitost koja spaja". Nostalgija Kako je saopšteno na konferenciji za novinare, na konkurs festivala pristigla su 193 rada iz Srbije, Crne Gore, BiH, Hrvatske, Slovenije, Makedonije, Ma đarske, i Bugarske, od kojih je odabrano 25 kompozicija koje će se na ći na finalnoj ve čeri Festivala Omladina 2012. Direktor festivala, kompozitor Gabor Len đel, najavio je da će o najboljim u česnicima odlu čivati internacionalini stru čni žiri koji će činiti Olja Deši ć iz Hrvatske, Tomaž Domicelj iz Slovenije, Brano Liki ć iz BiH i Peca Popovi ć iz Srbije. Len đel je najavio da će na Festivalu biti dodeljeno šest nagrada. "Takmi čarski deo festivala održa će se 8. decembra u 19 časova u Hali sportova, a u revijalnom delu nastupi će 'Bajaga i instruktori'. Prate ći program festivala uklju čuje 'Ve če nostalgije' koncertom Ibrice Jusi ća, 7. decembra u 19 časova u Velikoj ve ćnici Gradske ku će", kazao je on. Razli čiti muzi čki pravci Umetni čki direktor Festivala Kornelije Kova č izjavio je da će na festivalu biti zastupljeni razli čiti muzi čki pravci - od regea, preko popa i bluza, do repa. "Posebno raduje da smo ponovo uspeli da u festival uklju čimo ceo region jer na taj na čin ponovo uspostavljamo mostove koji su nekada bili porušeni. -

2009 08 12 AKTO 4 Catalog

279487115 АКТО_4 FESTIVAL FOR CONTEMPORARY ARTS TOPIC_GENERATIONS AKTO_4 Festival for Contemporary arts will be held from 12.08 - 16.08.09 in Bitola, Republic of Macedonia. Akto is a regional festival for contemporary art which includes visual arts, performing arts, music and theory of culture. The main objective of Akto Festival is to open the cultural frameworks of a modern society through “recomposing” and redifning them in a new context. The programme of the festival is based on two concepts. The frst concept is space/location_ Locations have been transformed in terms of their previous meanings. The basic idea of the festival is art pieces to come out of the standard location (galleries, museums, theatres) used for presenting art, and their setting up in new location. Re-moving of the pieces into new location transforms the piece itself (according to the parameter space). The second concept is the topic of the festival_ The topic of Akto_4 festival is Generations. The artistic pieces (according to the parameter Generations) are going to be presented in two categories: artistic pieces that have generations as a basic starting point and pieces that are transformation of an already fnished artistic forms (also according to the parameter Generations). The “new” piece is transformed from its basic form. It has new statics and dynamics. The topic Generations deals with the issue of generations and initiates several questions: Are the ties between today’s young generations with the generation of their parents broken? Are today’s young generations -

Prijedlozi Za Nominacije

glazbena nagrada 2021. SADRŽAJ OPĆE NAGRADE STR. 4-19 SVA GLAZBENA PODRUČJA 1 (KATEGORIJE 1-3) ALBUM GODINE PJESMA GODINE NOVI IZVOĐAČ GODINE POSEBNA GLAZBENA PODRUČJA STR. 20-35 ZABAVNA, POP, ROCK, ALTERNATIVNA, HIP HOP I ELEKTRONIČKA GLAZBA 2 (KATEGORIJE 4-13) NAJBOLJI ALBUM ZABAVNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM POP GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM ROCK GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM ALTERNATIVNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM HIP HOP GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM ELEKTRONIČKE GLAZBE NAJBOLJA ŽENSKA VOKALNA IZVEDBA NAJBOLJA MUŠKA VOKALNA IZVEDBA NAJBOLJA IZVEDBA GRUPE S VOKALOM NAJBOLJA VOKALNA SURADNJA JAZZ GLAZBA STR. 36-39 (KATEGORIJE 14-16) 3 NAJBOLJI ALBUM JAZZ GLAZBE NAJBOLJA SKLADBA JAZZ GLAZBE NAJBOLJA IZVEDBA JAZZ GLAZBE TAMBURAŠKA, POP- FOLKLORNA GLAZBA I WORLD MUSIC ALBUM STR. 40-43 4 (KATEGORIJE 17-19) NAJBOLJI ALBUM TAMBURAŠKE GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM POP-FOLKLORNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJI WORLD MUSIC ALBUM 2 ARANŽMAN, PRODUCENT GODINE, SNIMKA ALBUMA STR. 44-53 (IZVAN KLASIČNE GLAZBE) 5 (KATEGORIJE 20-22) NAJBOLJI ARANŽMAN PRODUCENT GODINE NAJBOLJA SNIMKA ALBUMA KLASIČNA GLAZBA STR. 56-61 (KATEGORIJE 23-27) 6 NAJBOLJI ALBUM KLASIČNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJA SKLADBA KLASIČNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJA IZVEDBA KLASIČNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJA SNIMKA ALBUMA KLASIČNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJA PRODUKCIJA ALBUMA KLASIČNE GLAZBE SVA GLAZBENA PODRUČJA STR. 62-77 (KATEGORIJE 28-36) 7 NAJBOLJI TEMATSKO-POVIJESNI ALBUM NAJBOLJI ALBUM POPULARNE DUHOVNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM BOŽIĆNE GLAZBE NAJBOLJI ALBUM S RAZNIM IZVOĐAČIMA NAJBOLJI KONCERTNI ALBUM NAJBOLJI INSTRUMENTALNI ALBUM (IZVAN KLASIČNE I JAZZ GLAZBE) 3 NAJBOLJA INSTRUMENTALNA IZVEDBA (IZVAN KLASIČNE I JAZZ GLAZBE) NAJBOLJI VIDEO BROJ NAJBOLJE LIKOVNO OBLIKOVANJE 4 3 OPĆE NAGRADE SVA GLAZBENA PODRUČJA (KATEGORIJE 1-3) ALBUM GODINE 1 PJESMA GODINE NOVI IZVOĐAČ GODINE 4 Kategorija 1 / ALBUM GODINE Ovo je kategorija za albume iz svih glazbenih područja s pretežno (51% ili više) novim snimkama. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2 | Messages and Voices Messages and Voices | 3

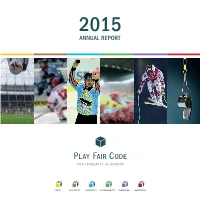

2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2 | Messages and Voices Messages and Voices | 3 “Betting fraud is the new threat to sport world- There is quite wide. With its education and training courses, consultations and information events, Play a lot to say about Fair Code is creating broad awareness of the threats of match-fixing. It is helping us protect the issue of our athletes and defend the integrity of sport.” match-fixing! Gerald KLUG AUSTRIAN MINISTER OF SPORT “People love to watch sports “We not only succeeded in organising nearly “Fairness and integrity are sport’s most im- 100 training and education courses aimed at portant attributes, and crucial prerequisites if because they don’t know our core target audiences in 2015; we also we want competitive sport to remain attrac- played an important role on the international tive – and that goes not just for spectators, stage once again, as a model for best prac- but also for the athletes themselves. Play Fair how it’s going to end!” tice. Play Fair Code has some extremely Code is playing a hugely important role in pre- Sepp Herberger exciting challenges facing it in the future, venting match-fixing in Austria, and by doing Former manager, German national football team especially the Council of Europe’s recent so, keeping sport clean, the way we all want it. Convention on the Manipulation of Sports That’s why I shall be continuing to work side- Competitions and the National Platform being by-side with Play Fair Code in 2016.” set up.” Günter KALTENBRUNNER Dietmar HOSCHER PRESIDENT, PLAY FAIR CODE BOARD OF DIRECTORS, CASINOS AUSTRIA „It has been a good thing to remind our-selves of this issue once again; it’s incre-dible just what vast sums of money the betting mafia are dealing with. -

ED121078.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME - ED 121 078 FL 007 541 AUTHOR Filipovic, Rudolf, Ed, TITLE Deports 4. The Yugoslav Serbo-Croatian-English ContrLstive Project. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.; Zagreb Univ. (Yugoslavia). Inst. of Linguistics, PUB DATE 71 NOTE 151p.; For related documents, see ED 096 839, ED 108 465, and FL 007 537-552 AVAILABLE FROMDorothy Rapp, Center for Applied Linguistics, 1611 N. Kent St., Arlington, Va. 22209 ($3.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$8.69 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Adverbs; *Contrastive Linguistics; Descriptive Linguistics; *English; Language Patterns; NominaIs; *Serbocroatian; Slavic Languages; *Syntax; *Verbs IDENTIFIERS *Tense (Verbs) ABSTRACT The fourth volume in this series contains nine articles dealing with various aspects of Serbo-Croatian-English contrastive analysis. They are: "Adverbial Clauses of Cause, Place and Manner in English and Serbo-Croatian," by Gordana Gavrilovic: "Intransitiv.t Verbs+Adverbials or Complements Containing Non-Finite Verb Forms," by Omer Hadziselimovic; "Number Agreement in English and Correspondent Structures in Serbo-Croatian," by Vladimir Ivir; "The Expression of Future Time in English and Serbo-Croatian," by Damir Kalogjera; "Additional Notes on Noun Phrases in the Function of Subject in English and Serbo-Croatian," by Ljiljana Mihailovic; "Elliptical sentences in English and Their Serbo-Croatian Equivalents," by Mladen Mihajlovic; "The English Preterit Tense and Its Serbo-Croatian Equivalents" and "The English Past Perfect Tense and Its Serbo - Croatian Equivalents," both by Leonardo Spalatin; and "Adverbial Modifiers in Intransitive Sentences in English and Serbo-Croatian," by Ljubica Vojnovic.(CLK) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources.