Introduction M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2015 PPI Tech/Info Job Ranking

POLICY BRIEF The 2015 PPI Tech/Info Job Ranking BY MICHELLE DI IONNO AND MICHAEL MANDEL NOVEMBER 2015 Introduction This policy brief reports the top 25 tech counties in the country, based on the 2015 PPI Tech/Info Job Index. The top three counties are in the Bay Area—first is San Francisco Country, followed by Santa Clara County (Silicon Valley), and San Mateo County. Travis County, home of Austin, Texas, takes fourth place, with Utah County (Provo, Utah) ranking fifth. The top 25 list also includes well-known tech hubs such as King County (Seattle), New York County (New York City), Middlesex County (Cambridge, Mass.) and Suf- folk County (Boston). However, the PPI Tech/Info Job Index also identifies some unexpectedly strong performers, including East Baton Rouge Parish (Baton Rouge, La.) and St. Charles County (St. Louis, Mo. Metro Area). The PPI Tech/Info This is the third year that we have ranked counties by the PPI Tech/Info Job Index, Index provides an which is based on the number of jobs added in their tech/info industries from 2011 to 2014, relative to the size of the local economy. PPI defines the tech/info sector as objective measure of including telecom, tech, and content industries, including wired and wireless tele- the importance of com, Internet search and publishing, and movie production (see complete list of in- telecom, tech, and cluded industries in the methodology section). content job growth to As in previous years, we find that the local economies with the highest PPI local economies. Tech/Info Job Index tend to have a faster growth rate of non-tech jobs. -

Policy Playbook for 2009

Part I: Initiative Guide Introduction: Coping with the Downturn, Keeping Focus 1 Jumpstart Oregon Stimulus Proposal 3 Taking Stock of What We Face 6 Oregon Business Plan Framework 8 Summary of Initiative Recommendations 12 Our Progress on Oregon Benchmarks 16 Part II: Cluster Guide Industry Clusters: The Structure of the Oregon Economy 21 Natural Resource Clusters 23 High Technology Clusters 39 Metals, Machinery, and Manufacturing Clusters 52 Sports Apparel and Recreation Product Clusters 58 Clean Technology Industry Clusters 61 2008-2009 Oregon Business Plan Steering Committee Steven D. Pratt (Chair), ESCO Corporation Eric Blackledge, Blackledge Furniture, At-large Member Sam Brooks, S. Brooks & Associates; Chair, Oregon Association of Minority Entrepreneurs David Chen, Equilibrium Capital; Chair, Oregon InC Robert DeKoning, Routeware, Inc.; Vice Chair, Oregon Council, AeA Kirby Dyess, Austin Capital Management; Oregon State Board of Higher Education Dan Harmon, Hoffman Corporation; Chair, Associated Oregon Industries Steve Holwerda, Fergusen Wellman Capital Management, Inc.; Chair, Portland Business Alliance Randolph L. Miller, The Moore Company; At-large Member Michael Morgan, Tonkin Torp, LLP.; Chair, Oregon Business Association Michael R. Nelson, Nelson Real Estate; Member, Oregon Transportation Commission Peggy Fowler, Portland General Electric; Chair, Oregon Business Council Walter Van Valkenburg, Stoel Rives LLP; Chair, Oregon Economic and Community Development Commission Brett Wilcox, Summit Power Alternative Resources; At-large -

High-Tech.Pdf

OREGON KEY INDUSTRIES Clean Technology Wood & Forest Products Advanced Manufacturing High Technology Outdoor Gear & Activewear Firms (2010): 7,997 Employees (2010): 84,285 SNAPSHOT Average Wage (2010): $86,126 Y Export Value (2011): $7.59 billion Sales (2007): $41.5 billion INDUSTR “There is a large pool of technical talent in Portland with Home to the Silicon Forest, the local concentration of high-tech companies the kind of skills we need, it is have made a name for Oregon across the globe. Three companies sparked the evolution of high-tech in Oregon: Tektronix in the 1960s, Mentor close to a wide range of outdoor Graphics in the ‘70s and Intel in the ‘80s. These companies have each activities, it is an incredible place spun-off hundreds of other startups, and evolved into a robust to live and an easy place to supply chain that can provide a competitive advantage to any technology company looking at expansion. recruit workers.” Matt Tucker The largest cluster of Oregon technology companies is located around the CTO & co-founder, Jive Software city of Hillsboro, anchored by Intel’s largest facility in the world and supported by a highly skilled and experienced workforce. This buildup of WWW.OREGON4BIZ.COM talent and infrastructure has spawned other sectors such as bioscience, digital displays and software development. Oregon is home to more than 1,500 software companies, and is particularly strong in the areas of finance, open source, education, mobile and healthcare applications. Healthcare-associated software companies have helped grow a strong bioscience industry that benefits from a renowned research facility in Oregon Health and Sciences University, located in Portland. -

Office Building on 18.95 Acres: Renovation Or Redevelopment Offering

COOLEY office building on 18.95 acres: renovation or redevelopment offering 9830 NE ECKERT DR HILLSBORO, OREGON Conceptual Entry TABLE OF EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 INVESTMENT OVERVIEW 6 CONTENTS THE COMMUNITY 8 RENOVATION CONCEPT PLANS 11 FLOOR PLANS 12 COMPARABLES 14 LOCATION 18 MARKET OVERVIEW 20 Conceptual EXECUTIVE S U M M A RY Colliers is pleased to present this dual-faced opportunity to own 18.95 acres COOLEY in AmberGlen, a neighborhood in east Hillsboro. AmberGlen includes a mixture of office and commercial areas with a growing number of high-density residential units being added as a result of the AmberGlen Community Plan. The AmberGlen Community Plan seeks to transform the neighborhood into high- density mixed uses catered to a larger residential base while preserving the 18.95 existing office uses. New developments include Aloft Hotels, a 136-room hotel acres opened in 2017; The Arbory and Windsor Apartments, both completed in 2018 and adding 325 units. Equally opportunistic is the vision of a high-amenity corporate office setting. The existing 68,000 RSF building once functioned as institutional lab space for OHSU. The unique design and base building structure offers incredible renovation opportunities for the discriminate corporate user. Renderings throughout this brochure have been originated by GBD architects to assist in visualizing a modern look with contemporary elements for today’s dynamic office user. COOLEY OFFICE BUILDING | OFFERING MEMORANDUM COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL P. 5 LOCATION INVESTMENT The site is located in the AmberGlen Business Park near the Tanasbourne retail environment along NW 185th Ave and Highway 26. This area is COOLEY established as a regional retail hub at the gateway to the high-tech corridor known locally as the Silicon Forest. -

CSET Issue Brief

SEPTEMBER 2020 The Chipmakers U.S. Strengths and Priorities for the High-End Semiconductor Workforce CSET Issue Brief AUTHORS Will Hunt Remco Zwetsloot Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 3 Key Findings ...................................................................................................... 3 Workforce Policy Recommendations .............................................................. 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 7 Why Talent Matters and the American Talent Advantage .............................. 10 Mapping the U.S. Semiconductor Workforce .................................................. 12 Identifying and Analyzing the Semiconductor Workforce .......................... 12 A Large and International Workforce ........................................................... 14 The University Talent Pipeline ........................................................................ 16 Talent Across the Semiconductor Supply Chain .......................................... 21 Chip Design ................................................................................................ 23 Electronic Design Automation ................................................................... 24 Fabrication .................................................................................................. 24 Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment (SME) Suppliers -

WASHINGTON STREET STATION 20 Units • Hillsboro, Oregon OFFERING MEMORANDUM

WASHINGTON STREET STATION 20 Units • Hillsboro, Oregon OFFERING MEMORANDUM www.hfore.com (503) 241.5541 2 HFO INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ASSET SUMMARY DETAILED UNIT MIX Location 433 SE Washington Street Unit Type Unit Count Average Sq Ft Total Sq Ft % of Total Units City, State Hillsboro, OR 97123 1 Bed / 1 Bath 2 548 1,096 10.0% County Washington 1 Bed / 1 Bath 8 600 4,800 40.0% 2 Bed/ 2 Bath Total Units 20 6 1,243 7,458 30.0% Townhome Year Built 2012 2 Bed / 2 Bath 4 1,330 5,320 20.0% Approx. NR Sq Ft 18,674 Total / Averages 20 934 18,674 100.0% Average Unit Size 934 Washington Street Station is a 20-unit community in the heart of downtown PRICE SUMMARY Hillsboro. The property offers tenants spacious one-bed, one-bath and large two- bed, two-bath layouts. Apartments average 934 square feet and have modern Price $4,400,000 fixtures and amenities throughout. Price Per Unit $220,000 Washington Street Station is situated on SE Washington Street between SE 4th and Per Square Foot $236 5th Streets just one block from the Hillsboro Central MAX station. Its accessible Projected Cap Rate 5.91% location offers numerous amenities within walking distance including Walgreens, Starbucks, Insomnia Coffee, Shute Park, Tuality Community Hospital, and an abundance of restaurants and retailers. Washington Street Station’s rents currently TOURS AND INQUIRIES average $1,409 per unit or $1.51 per square foot; projected rents average $1,480 per unit or $1.58 per sq ft. -

Tektronix Oscilloscope by Oregon Journal This Photograph Depicts a Tektronix Employee Studying an Invention by the Company--A Storage Oscilloscope

Tektronix Oscilloscope By Oregon Journal This photograph depicts a Tektronix employee studying an invention by the company--a storage oscilloscope. The Washington County high-technology firm's new products recorded faster electronic signals than other oscilloscopes on the market. Recognition for its oscilloscopes was nothing new to Tektronix. Research institutions and government laboratories had acknowledged Tektronix's superior product by the 1950s. Business soared as the company met the demands of the Korean War and the emerging television and computer industries. The company's success continued into the 1960s and 1970s. The company's 7834 storage oscilloscope gained accolades for Tektronix by winning a prestigious annual industrial research design award that identified it as one of the top one hundred technical innovations of 1977. Its high profits allowed it to invest resources into research and development projects and educational programs designed to keep employees current on new developments in the field. The number of firms specializing in high technology in the Portland area boomed during the 1960s; whereas there had been five companies in 1950, there were twenty-two by 1962. Tektronix led the pack in employees and sales figures. By 1980 it was the largest private employer in Oregon and was helping revive the state's economy after the deterioration of the timber industry in the late 1970s. The company's size and influence helped gain notoriety for the Tualatin Valley as a high-technology center, and soon the media began referring to the area as the Silicon Forest, a reference to the Silicon Valley in Santa Clara, California. -

Tech Entrepreneurs Defy Rec

Tech entrepreneurs defy recession http://blog.oregonlive.com/business_impact/print.html?entry=/2009/05/te... Tech entrepreneurs defy recession By Mike Rogoway, The Oregonian May 01, 2009, 9:10PM Photo by Olivia Bucks/The Oregonian T.J. VanSlyke, right, helps Christine Alex with her blogs at Beer and Blog, a weekly meetup of Oregon techies in Southeast Portland. Here's what the recession feels like among Portland's new breed of high-spirited, high-tech entrepreneurs: Any night of the week you'll find software developers and Web designers sharing coffee or beer in cubicles, lofts, bars, cafes and theaters. It's business and pleasure wrapped together. These aren't the heads-down geeks of yore, but a hyper-social, mixed-gender crew shouting out to one another across Twitter, Facebook and a score of other online communities. Even as Intel, Hewlett-Packard, Tektronix and other Oregon tech stalwarts are slashing jobs, new companies are springing up by the bushel in Old Town, the Pearl and Portland's inner eastside. These startups are taking advantage of the social media craze to invent new Web tools that broadcast a user's location online, for example, or stream advertising onto MySpace and other online communities. But stalwarts they are not, and may never be, even as the state looks for ways out of its deepening recession. Oregon has long lacked the money, scale and leadership to be a great incubator for tech startups. Those weaknesses are less important these days, as the recession humbles big cities and mega-companies. The trend toward grass-roots technology Online chat and collaboration plays to Portland's strengths. -

Sunset Science Park

Sunset Science Park By State of Oregon, Department of Planning and Development This 1962 aerial photograph depicts a section of Beaverton bordered by the Sunset Highway between Cornell and Murray roads. The cluster of buildings near the center of the photograph is Sunset High School. The photograph appeared in a state publication, Grow with Oregon. The accompanying article announced a groundbreaking ceremony for Sunset Science Park. Broken white lines on the photograph highlight the construction site. Electro Scientific Industries (ESI), a well established Portland manufacturer of high-precision electronic equipment, purchased the one-hundred-acre site to build an industrial park modeled after Science Park near Stanford University in California. The idea was to attract science-oriented manufacturing industries interested in research and development by creating a complex that resembled a college campus. Many local citizens did not initially approve of the park - which was designed to house the clean plants of light industry - because they associated all industry with dirty smokestacks. The site's proximity to schools, recreation centers, and housing developments concerned them. Support of the project by Governor Mark Hatfield helped ESI officials win over the community. ESI's move to the science park resulted from the company's steady growth since its beginning as Brown Engineering Company, which had manufactured impedance bridges during World War II. Impedance bridges, devices that measure alternating-current resistance in electrical equipment, continued to be the company's primary product after Douglas Strain, a partner, purchased the company with his father in 1953 and changed its name to ESI. The U.S. -

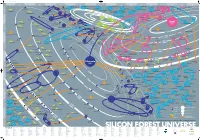

Silicon Forest Universe

15239 Poster 9/16/02 1:03 PM Page 1 AB CDE FGH I JKL M N O P Q R S Pearlsoft COMSAT General Integrated Systems Ashwood Group '85 Qualis Design fka CPU International Nel-Tech Development '98 Qsent '01 Briefsmart.com '00 Relyent TrueDisk Trivium Systems '80 '74 '99 '90 Gearbeat '81 Relational Systems Galois 3DLand Teradyne in 2001 '85 '00 '98 Solution Logic SwiftView Imagenation '89 Metro One IronSpire '84 Smart Mediary Systems Connections 13 Telecommunications WireX GenRad in 1996 '00 CyberOptics E-Core Salu Logiplex '79 MyHealthBank Semiconductor Cotelligent Technologies Fujitsu America Barco Metheus '77 '99 Group Knowledge fka United Data Biotronik Timlick & Associates in 1999 Gadget Labs Adaptive Solutions Wave International Processing Cascade Laser '98 Webridge Axis Clinical Software Mitron Basicon '91 GemStone fka Servio Logic Source Services '83 Integra Telecom Accredo FaxBack Polyserve Metheus Intersolv Babcock & Jenkins Electro '79 Informedics Scientific Sliceware Graphic Software Systems Industries IBM 12 in 1999 Atlas Telecom 1944 Sequent Computer ProSight Credence in 2001 19 ADC Kentrox '78 Oracle '69 Merant Datricon 60s Informix Systems FEI Sage Software fka Polytron MKTX 197 Mikros Nike 0s Etec Systems '63 19 Sentrol in 1995 Intel 80s SEH America Teseda Oregon Graduate Institute Flight Dynamics 1976 '97 1990 Purchasing Solutions Fluence ~ Relcom Vidco Mushroom Resources Cunningham & Cunningham '99 Myteam.com Praegitzer Industries Integrated Measurement Systems Zicon Digital World Lucy.Com Nonbox in 2001 ATEQ 11 Software Access -

Silicon Forest and Server Farms: the (Urban) Nature of Digital Capitalism in the Pacific Northwest

CULTURE MACHINE CM • 2019 Silicon Forest and Server Farms: The (Urban) Nature of Digital Capitalism in the Pacific Northwest Anthony M Levenda (Arizona State University) and Dillon Mahmoudi (University of Maryland, Baltimore County) Introduction Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified. The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and been transformed in accordance with it. To what degree the powers of social production have been produced, not only in the form of knowledge, but as immediate organs of social practice, of the real life process. (Marx, 1973: 706) Access to inexpensive hydro-resources, such as hydro- electricity and water for cooling, cheap land, and proximity to undersea networks have created a spatial sweet spot for big tech companies such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon in the Pacific Northwest. These factors are leveraged as ‘natural’ reasons for the growth of the data center industry in the region, often accompanied by promises of new jobs and a rhetoric of economic transition from forestry to data. In reality, broader social and environmental implications are neglected in deference to companies that sell visions of big-data-driven economic growth for local communities devastated by crises of capital. -

Strategies for Innovative and Effective ICT Components & Systems Manufacturing in Europe

Strategies for Innovative and Effective ICT Components & Systems Manufacturing in Europe Case Studies Annex ANNEX TO THE FINAL REPORT A study prepared for the European Commission DG Communications Networks, Content & Technology This study was carried out for the European Commission by Authors : Gabriella Cattaneo, Stefania Aguzzi, Alain Pétrissans, Stéphane Krawczyk, Sebastien Lamour, Henrik Noes Piester, Malene Stidsen Internal identification Contract number: 30-CE-0455328/00-14 SMART number: 2011/0063 DISCLAIMER By the European Commission, Directorate-General of Communications Networks, Content & Technology. The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. ISBN 978-92-79-30927-4 DOI: 10.2759/24160 Copyright © European Union, 2013. All rights reserved. Certain parts are licensed under conditions to the EU. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. 2 2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Figures ..................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Tables......................................................................................................................