Effective Consultation and Participation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

®V ®V ®V ®V ®V

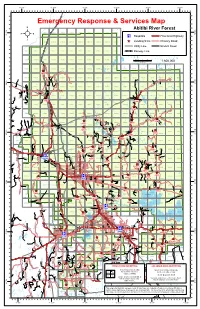

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 82°0'W 81°30'W 81°0'W 80°30'W 80°0'W 79°30'W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N ' N ' 0 0 3 ° 3 ! ° 450559 460559 470559 480559 490559 500559 510559 520559 530559 0 0 5 5 ! v® Hospitals Provincial Highway ! ² 450558 460558 470558 480558 490558 500558 510558 520558 530558 ^_ Landing Sites Primary Road ! ! ! ! Utility Line Branch Road 430557 440557 450! 557 460557 470557 480557 490557 500557 510557 520557 530557 Railway Line ! ! 430556 440556 450556 460556 470556 480556 490556 500556 510556 520556 530556 5 2.5 0 5 10 15 ! Kilometers 1:800,000 ! ! ! ! 45! 0! 555 430555 440555 460555 470555 480555 490555 500555 510555 520555 530555 540555 550555 560555 570555 580555 590555 600555 ! ad ! ! o ^_ e R ak y L dre ! P u ! A O ! it t 6 t 1 e r o 430554 440554 450554 460554 470554 480554 490554 500554 510554 520554 530554 540554 550554 560554 570554 580554 590554 600554 r R R d! o ! d a y ! a ad a p H d o N i ' N o d R ' 0 ! s e R n ° 0 i 1 ° ! R M 0 h r d ! ! 0 u c o 5 Flatt Ext a to red ! F a a 5 e o e d D 4 R ! B 1 430553 440553 45055! 3 460553 470553 480553 490553 500553 510553 520553 530553 540553 550553 560553 570553 580553 590553 600553 R ! ! S C ! ! Li ttle d L Newpost Road ! a o ! ng ! o d R ! o R a a o d e ! R ! s C ! o e ! ! L 450552! ! g k i 430552 440552 ! 460552 470552 480552 490552 500552 510552 520552 530552 540552 550552 560552 570552 580552 590552 600552 C a 0 e ! n ! L U n S 1 i o ! ! ! R y p L ! N a p l ! y 8 C e e ^_ ! r k ^_ K C ! o ! S ! ! R a m t ! 8 ! t ! ! ! S a ! ! ! w ! ! 550551 a ! 430551 440551 450551 -

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit Kapuskasing Iroquois Falls Hearst Timmins Porcupine Cochrane Moosonee Hornepayne Matheson Smooth Rock Falls Population Profile Foyez Haque, MBBS, MHSc Public Health Epidemiologist published by: Th e Porcupine Health Unit Timmins, Ontario October 2009 ©2009 Population Profile - 2006 Census Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude to those without whose support this Population Profile would not be published. First of all, I would like to thank the management committee of the Porcupine Health Unit for their continuous support of and enthusiasm for this publication. Dr. Dennis Hong deserves a special thank you for his thorough revision. Thanks go to Amanda Belisle for her support with editing, creating such a wonderful cover page, layout and promotion of the findings of this publication. I acknowledge the support of the Statistics Canada for history and description of the 2006 Census and also the definitions of the variables. Porcupine Health Unit – 1 Population Profile - 2006 Census 2 – Porcupine Health Unit Population Profile - 2006 Census Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 1 Preface . 5 Executive Summary . 7 A Brief History of the Census in Canada . 9 A Brief Description of the 2006 Census . 11 Population Pyramid. 15 Appendix . 31 Definitions . 35 Table of Charts Table 1: Population distribution . 12 Table 2: Age and gender characteristics. 14 Figure 3: Aboriginal status population . 16 Figure 4: Visible minority . 17 Figure 5: Legal married status. 18 Figure 6: Family characteristics in Ontario . 19 Figure 7: Family characteristics in Porcupine Health Unit area . 19 Figure 8: Low income cut-offs . 20 Figure 11: Mother tongue . -

(De Beers, Or the Proponent) Has Identified a Diamond

VICTOR DIAMOND PROJECT Comprehensive Study Report 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Overview and Background De Beers Canada Inc. (De Beers, or the Proponent) has identified a diamond resource, approximately 90 km west of the First Nation community of Attawapiskat, within the James Bay Lowlands of Ontario, (Figure 1-1). The resource consists of two kimberlite (diamond bearing ore) pipes, referred to as Victor Main and Victor Southwest. The proposed development is called the Victor Diamond Project. Appendix A is a corporate profile of De Beers, provided by the Proponent. Advanced exploration activities were carried out at the Victor site during 2000 and 2001, during which time approximately 10,000 tonnes of kimberlite were recovered from surface trenching and large diameter drilling, for on-site testing. An 80-person camp was established, along with a sample processing plant, and a winter airstrip to support the program. Desktop (2001), Prefeasibility (2002) and Feasibility (2003) engineering studies have been carried out, indicating to De Beers that the Victor Diamond Project (VDP) is technically feasible and economically viable. The resource is valued at 28.5 Mt, containing an estimated 6.5 million carats of diamonds. De Beers’ current mineral claims in the vicinity of the Victor site are shown on Figure 1-2. The Proponent’s project plan provides for the development of an open pit mine with on-site ore processing. Mining and processing will be carried out at an approximate ore throughput of 2.5 million tonnes/year (2.5 Mt/a), or about 7,000 tonnes/day. Associated project infrastructure linking the Victor site to Attawapiskat include the existing south winter road and a proposed 115 kV transmission line, and possibly a small barge landing area to be constructed in Attawapiskat for use during the project construction phase. -

BY COURIER July 31, 2014 Ms. Kirsten Walli Secretary Ontario

Hydro One Networks Inc. 7th Floor, South Tower Tel: (416) 345-5700 483 Bay Street Fax: (416) 345-5870 Toronto, Ontario M5G 2P5 Cell: (416) 258-9383 www.HydroOne.com [email protected] Susan Frank Vice President and Chief Regulatory Officer Regulatory Affairs BY COURIER July 31, 2014 Ms. Kirsten Walli Secretary Ontario Energy Board Suite 2700, 2300 Yonge Street P.O. Box 2319 Toronto, ON. M4P 1E4 Dear Ms. Walli: EB-2014-0244 – MAAD S86 Hydro One Networks Inc. Application to Purchase Haldimand County Utilities Inc. I am attaching two (2) paper copies of Hydro One Inc’s MAAD Application for the acquisition of Haldimand County Utilities Inc. Please note that information has been redacted in Exhibit A, Tab 3, Schedule 1, Attachment 6 pertaining to employee, property owner, and account information. An electronic copy of the complete application has been filed using the Board’s Regulatory Electronic Submission System. Sincerely, ORIGINAL SIGNED BY SUSAN FRANK Susan Frank attach. Filed: 2014-07-31 EB-2014-0244 Exhibit A Tab 1 Schedule 1 Page 1 of 6 1 ONTARIO ENERGY BOARD 2 3 IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c. 15 (the “Act”). 4 5 IN THE MATTER OF an application made by Hydro One Inc. for leave for Hydro One Inc., 6 acting through its subsidiary 1908872 Inc.. (referred to collectively hereinafter as “Hydro One 7 Inc.”) to purchase all of the issued and outstanding shares of Haldimand County Utilities Inc., 8 made pursuant to section 86(2)(b) of the Act. -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

Table of Contents/Table De Matières

Comptes publics de l’ Public Accounts of Ministry Ministère of des Finance Finances PUBLIC COMPTES ONTARIOONTARIO ACCOUNTS PUBLICS of de ONTARIO L’ONTARIO This publication is available in English and French. CD-ROM copies in either language may be obtained from: ServiceOntario Publications Telephone: (416) 326-5300 Toll-free: 1-800-668-9938 2011–2012 TTY Toll-free: 1-800-268-7095 Website: www.serviceontario.ca/publications For electronic access, visit the Ministry of Finance website at www.fin.gov.on.ca Le présent document est publié en français et en anglais. 2011-2012 On peut en obtenir une version sur CD-ROM dans l’une ou l’autre langue auprès de : D E TA I L E D S C H E D U L E S Publications ServiceOntario Téléphone : 416 326-5300 Sans frais : 1 800 668-9938 O F P AY M E N T S Téléimprimeur (ATS) sans frais : 1 800 268-7095 Site Web : www.serviceontario.ca/publications Pour en obtenir une version électronique, il suffit de consulter le site Web du ministère des Finances à www.fin.gov.on.ca D ÉTAILS DES PAIEMENTS © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012 © Imprimeur de la Reine pour l’Ontario, 2012 ISSN 0381-2375 (Print) / ISSN 0833-1189 (Imprimé) ISSN 1913-5556 (Online) / ISSN 1913-5564 (En ligne) Volume 3 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DE MATIÈRES Page General/Généralités Guide to Public Accounts.................................................................................................................................. 3 Guide d’interprétation des comptes publics ...................................................................................................... 5 MINISTRY STATEMENTS/ÉTATS DES MINISTÈRES Aboriginal Affairs/Affaires autochtones ........................................................................................................... 7 Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs/Agriculture, Alimentation et Affaires rurales......................................... -

2017, Jones Road, Near Blackhawk, RAIN (Photo: Michael Dawber)

Edited and Compiled by Rick Cavasin and Jessica E. Linton Toronto Entomologists’ Association Occasional Publication # 48-2018 European Skippers mudpuddling, July 6, 2017, Jones Road, near Blackhawk, RAIN (Photo: Michael Dawber) Dusted Skipper, April 20, 2017, Ipperwash Beach, LAMB American Snout, August 6, 2017, (Photo: Bob Yukich) Dunes Beach, PRIN (Photo: David Kaposi) ISBN: 978-0-921631-53-7 Ontario Lepidoptera 2017 Edited and Compiled by Rick Cavasin and Jessica E. Linton April 2018 Published by the Toronto Entomologists’ Association Toronto, Ontario Production by Jessica Linton TORONTO ENTOMOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION Board of Directors: (TEA) Antonia Guidotti: R.O.M. Representative Programs Coordinator The TEA is a non-profit educational and scientific Carolyn King: O.N. Representative organization formed to promote interest in insects, to Publicity Coordinator encourage cooperation among amateur and professional Steve LaForest: Field Trips Coordinator entomologists, to educate and inform non-entomologists about insects, entomology and related fields, to aid in the ONTARIO LEPIDOPTERA preservation of insects and their habitats and to issue Published annually by the Toronto Entomologists’ publications in support of these objectives. Association. The TEA is a registered charity (#1069095-21); all Ontario Lepidoptera 2017 donations are tax creditable. Publication date: April 2018 ISBN: 978-0-921631-53-7 Membership Information: Copyright © TEA for Authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Annual dues: reproduced or used without written permission. Individual-$30 Student-free (Association finances permitting – Information on submitting records, notes and articles to beyond that, a charge of $20 will apply) Ontario Lepidoptera can be obtained by contacting: Family-$35 Jessica E. -

Reliability Performance Overview February 21, 2018 Agenda

First Nations – Reliability Performance Overview February 21, 2018 Agenda Hydro One Operations Review Historical Reliability Performance First Nations Communities Supply 2017 Transmission Reliability Transmission Reliability Improvements 2017 Distribution Reliability Distribution Grid Modernization Planned Work on Assets Serving First Nations Communities 2 Privileged and Confidential – Internal Use Only TOR 170419 Operations Performance ... HYDRO ONE OPERATIONS REVIEW 1005 Distribution Stations 3 Privileged and Confidential – Internal Use Only TOR 170419 Operations Performance ... First Nations Communities Supply Distribution Lines - “Feeders” Generating Step-Up Transmission Step-down Distribution Customer Station Lines Transmission Transformer Stations (First Nation Stations Communities) First Nations Communities: Supplied from 68 Transmission Lines, 59 Transmission Delivery Points and 109 Distribution Feeders 4 4 Privileged and Confidential – Internal Use Only TOR 170419 Operations Performance ... 2017 Transmission System Reliability Performance 2017 Year End Overall Transmission Performance: SAIDI was 42.8 min and SAIFI was 1.1 interruptions per customer delivery point. Main causes of these interruptions are 1) Weather 2) Defective Equipment and 3) Unconfirmed 5 Privileged and Confidential – Internal Use Only TOR 170419 Operations Performance ... Tx System – Primary Causes of Interruptions: (~66% from Weather & Equipment Failures) Power outage causes (2017) Weather 48% Adverse weather (freezing rain, ice, lightning) Equipment -

Appendix a IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (Previously Submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013

Summary of Consultation to Support the Côté Gold Project Closure Plan Côté Gold Project Appendix A IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (previously submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013 Stakeholder Consultation Plan (2013) TC180501 | October 2018 CÔTÉ GOLD PROJECT PROVINCIAL INDIVIDUAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROPOSED TERMS OF REFERENCE APPENDIX D PROPOSED STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION PLAN Submitted to: IAMGOLD Corporation 401 Bay Street, Suite 3200 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2Y4 Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, a Division of AMEC Americas Limited 160 Traders Blvd. East, Suite 110 Mississauga, Ontario L4Z 3K7 July 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Provincial EA and Consultation Plan Requirements ........................................... 1-1 1.3 Federal EA and Consultation Plan Requirements .............................................. 1-2 1.4 Responsibility for Plan Implementation .............................................................. 1-3 2.0 CONSULTATION APPROACH ..................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Stakeholder Identification .................................................................................. -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: an Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: An Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents Superior-Greenstone District School Board 2014 2 Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region Acknowledgements Superior-Greenstone District School Board David Tamblyn, Director of Education Nancy Petrick, Superintendent of Education Barb Willcocks, Aboriginal Education Student Success Lead The Native Education Advisory Committee Rachel A. Mishenene Consulting Curriculum Developer ~ Rachel Mishenene, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Edited by Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student and M.Ed. I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution in the development of this resource. Miigwetch. Dr. Cyndy Baskin, Ph.D. Heather Cameron, M.A. Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Martha Moon, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Brian Tucker and Cameron Burgess, The Métis Nation of Ontario Deb St. Amant, B.Ed., B.A. Photo Credits Ruthless Images © All photos (with the exception of two) were taken in the First Nations communities of the Superior-Greenstone region. Additional images that are referenced at the end of the book. © Copyright 2014 Superior-Greenstone District School Board All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Superior-Greenstone District School Board Office 12 Hemlo Drive, Postal Bag ‘A’, Marathon, ON P0T 2E0 Telephone: 807.229.0436 / Facsimile: 807.229.1471 / Webpage: www.sgdsb.on.ca Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region 3 Contents What’s Inside? Page Indian Power by Judy Wawia 6 About the Handbook 7 -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties.