Economy 103-126

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

BC Agents Deployed by the Bank

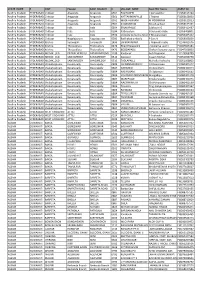

ZONE_NAM SOL_I STATE_NAME E DIST Mandal BASE_BRANCH D VILLAGE_NAME Bank Mitr Name AGENT ID Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 EACHANERI L Somasekhar FI2056105194 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 KATTAKINDAPALLE C Padma FI2056108800 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 MADHAVARAM M POORNIMA FI2056102033 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 PAIMAGHAM N Joshua Paul FI2056105191 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Irala Irala 0594 ERLAMPALLE Subhasini G FI2059410467 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Irala Irala 0594 Pathapalem G Surendra Babu FI2059408801 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Irala Irala 0594 Venkata Samudra AgraharamP Bhuvaneswari FI2059405192 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Nagalapuram Nagalapuram 0590 Baithakodiembedu P Santhi FI2059008839 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Krishna Surampalli Surampalli 1496 CHIKKAVARAM L Nagendra babu FI2149601676 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Krishna Thotavalluru Thotavalluru 0476 BhadriRajupalem J Sowjanya Laxmi FI2047605181 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Krishna Thotavalluru Thotavalluru 0476 BODDAPADU Chekuri Suryanarayana FI2047608950 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD MEDAK_OLD PATANCHERUVU PATANCHERUVU 1239 Kardanur Auti Rajeswari FI2123908799 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD MEDAK_OLD SANGAREDDY SANGAREDDY 0510 Kalabgor Ayyam Mohan FI2051008798 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD MEDAK_OLD SANGAREDDY SANGAREDDY 0510 TADLAPALLE Malkolla Yashodha FI2051008802 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Visakahaptnam Devarapally Devarapally 0804 CHINANANDIPALLE G.Dhanalaxmi -

Details of Grant-In-Aid Released Under Shelter House Scheme in 2012-2013 AWBI Code Amount S.No Name of Organization Address District State No

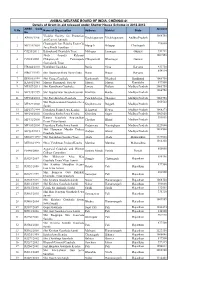

ANIMAL WELFARE BOARD OF INDIA, CHENNAI-41 Details of Grant-in-aid released under Shelter House Scheme in 2012-2013 AWBI Code Amount S.No Name of Organization Address District State No. Visakha Society for Protection 1068750 1 AP016/1998 Visakhapatnam Visakhapatnam Andhra Pradesh and Care of Animals Chattisgarh Jeev Raksha Evam Go 995805 2 MP224/2001 Mungeli Bilaspur Chattisgarh Seva Shodh Sansthan 3 GJ255/2011 Balmukund Charitable Trust Mithapur Jamnagar Gujarat 731241 Sheth Anandji Kalyanji 1061550 4 GJ188/2002 Chhapariyali Panjarapole Chhapariyali Bhavnagar Gujarat Ssarvajanik Trust 5 HR244/2010 Namdhari Gaushala Rania Sirsa Haryana 933750 854994 6 HR011/1991 Shri Gaushala Shala Dairy Datta Hansi Hissar Haryana 7 BH010/1999 Shri Ganga Gaushala Kankomath Dhanbad Jharkhand 1068750 8 KA001/1965 Mysore Pinjarapole Society Mysore Mysore Karnataka 877500 9 MP367/2011 Shri Kamdhenu Gaushala Jawara Ratlam Madhya Pradesh 1068750 1068750 10 MP135/1999 Shri Gupteshwar Gaushala Samiti Khirkiya Harda Madhya Pradesh 11 MP354/2010 Shri Ram Krishna Gaushala Panchdehariya Shajapur Madhya Pradesh 1068750 Shri Raghawanand Gaushala Seva 1055520 12 MP329/2008 Khejdameena Rajgarh Madhya Pradesh Samiti 13 MP137/1999 Dayodaya Pashu Sewa Kendra Behrawad Dewas Madhya Pradesh 1068273 14 MP256/2002 Dayodaya Pashu Sewa Kendra Khimlasa Sagar Madhya Pradesh 1003050 Karuna Gaushala Anusandhan 999859 15 MP332/2008 Chachar Bhind Madhya Pradesh Evam Vikas Samiti 16 MP186/2000 Dayodaya Pashu Sewa Samiti Gadarwara Narsinghpur Madhya Pradesh 1125000 Shri Hanuman Mandir -

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Dr. Muhammad Hameed

Dr. Muhammad Hameed Chairman Associate Professor Department of Archaeology University of the Punjab (Archaeologist, Historian, Museologist, Field Expert, Heritage Expert) Profile Completed MA in Archaeology from University of the Punjab in 2004. Dr. Hameed joined Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab as Lecturer in 2006. After serving the university for five years and getting overseas scholarship, he went to Berlin, Germany and completed his PHD in Gandhara Art, in 2015 from Free University Berlin. During his stay in Berlin, got several opportunity to become a part of the international research circle and attended international conferences, symposiums and workshops, about different aspects of South Asian Archaeology, held in Paris, Stockholm, Berlin, and Torun. The main research focuses on Buddhist Art with special interest in the Miniature Portable Shrines from Gandhara and Kashmir. The PHD dissertation provides the first catalogue of these objects. Study of origin of miniature portable shrines, their, types, iconography and religious significance are the main features of my research. Articles related to research areas have been published in HEC recognized journals as well as in international journals. Personal Info S/O: Muhammad Rafique DOB: 16-09-1981 NIC: 35401-9809372-3 Domicile: Sheikhupura (Punjab) Nationality: Pakistani Contact Info Off.: 042-99230322 Mobile: 03344063481 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Address: Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab, Lahore Pakistan Experience February -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Report on International Religious Freedom 2006: India

India Page 1 of 22 India International Religious Freedom Report 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respected this right in practice. However, the Government sometimes did not act swiftly enough to counter effectively societal attacks against religious minorities and attempts by some leaders of state and local governments to limit religious freedom. This resulted in part from legal constraints on national government action inherent in the country's federal structure and from shortcomings in its law enforcement and justice systems, although courts regularly upheld the constitutional provision of religious freedom. Despite Government efforts to foster communal harmony, some extremists continued to view ineffective investigation and prosecution of attacks on religious minorities, particularly at the state and local level, as a signal that they could commit such violence with impunity, although numerous cases were in the courts at the end of the reporting period. While the National Government took positive steps in key areas to improve religious freedom, the status of religious freedom generally remained the same during the period covered by this report. The United Progressive Alliance (UPA) continued to implement an inclusive and secular platform based on respect for the country's traditions of secular government and religious tolerance, and the rights of religious minorities. Terrorists attempted to provoke religious conflict by attacking Hindu Temples in Ayodhya and Varanasi. The Government reacted in a swift manner to rein in Hindu extremists, prevent revenge attacks and reprisal, and assure the Muslim community of its safety. -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Minutes of the Meet

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Minutes of the meeting of the Project Approval Board held on 14th June, 2018 to consider the Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B) 2018-19 of Samagra Shiksha for the State of Rajasthan. 1. INTRODUCTION The meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) for considering the Annual Work Plan and Budget (AWP&B) 2018-19 under Samagra Shiksha for the State of Rajasthan was held on 14-06-2018. The list of participants who attended the meeting is attached at Annexure-I. Sh Maneesh Garg, Joint Secretary (SE&L) welcomed the participants and the State representatives led by Shri Naresh Pal Gangwar, Secretary (Education), Government of Rajasthan and invited them to share some of the initiatives undertaken by the State. 2. INITIATIVES OF THE STATE Adarsh and Utkrisht Vidyalaya Yojana: An Adarsh Vidyalaya (KG/Anganwadi-XII) has been developed in each Gram Panchayat as center of excellence. An Utkrisht Vidyalaya (KG/Anganwadi-VIII) has also been developed in each Gram Panchayat under the mentorship of Adarsh school to ensure quality school coverage for other villages in the Gram Panchayat. Panchayat Elementary Education Officer- Principals of Adarsh school have been designated as ex-officio Panchayat Elementary Education Officer (PEEO) to provide leadership and mentorship to all other government elementary schools in the Gram Panchayat. These PEEOs have been designated as Cluster Resource Centre Facilitator (CRCF) for effective monitoring. Integration of Anganwadi centers with schools- Around 38000 Anganwadi centers have been integrated with schools having primary sections for improving pre-primary education under ECCE program of ICDS. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Gujarat State

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENEATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUNDWATER YEAR BOOK – 2018 - 19 GUJARAT STATE REGIONAL OFFICE DATA CENTRE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD May - 2020 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENEATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUNDWATER YEAR BOOK – 2018 -19 GUJARAT STATE Compiled by Dr.K.M.Nayak Astt Hydrogeologist REGIONAL OFFICE DATA CENTRE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD May - 2020 i FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board, West Central Region, has been issuing Ground Water Year Book annually for Gujarat state by compiling the hydrogeological, hydrochemical and groundwater level data collected from the Groundwater Monitoring Wells established by the Board in Gujarat State. Monitoring of groundwater level and chemical quality furnish valuable information on the ground water regime characteristics of the different hydrogeological units moreover, analysis of these valuable data collected from existing observation wells during May, August, November and January in each ground water year (June to May) indicate the pattern of ground water movement, changes in recharge-discharge relationship, behavior of water level and qualitative & quantitative changes of ground water regime in time and space. It also helps in identifying and delineating areas prone to decline of water table and piezometric surface due to large scale withdrawal of ground water for industrial, agricultural and urban water supply requirement. Further water logging prone areas can also be identified with historical water level data analysis. This year book contains the data and analysis of ground water regime monitoring for the year 2018-19. -

Religious Spots Within Forts and Fort Sites

Eurasian Journal of Humanities Vol. 1. Issue 1. (2015) ISSN: 2413-9947 Religious spots within forts and fort sites: a study in cultural history of Bundelkhand region in India Purushottam Singh Vikramajit Singh Sanatan Dharm College Kanpur India [email protected] Abstract Bundelkhand geographically situated in exactly the south of the Ganges plane is memorable due to the ancient references. Firstly, saints, devotees, hermits were attracted from Ganges plane towards the isolated, solitary pleasing zone of Vindhyatavi. (Singh, Rajendra, 1994, pp.1, 2) The history of Bundelkhand starts from the Chedi dynasty. (Singh, Rajendra, 1990, pp.80-85) The two famous cities of that time Shuktimati and Shahgeet are now a matter of research. After Chedis, Gupta rulers and Harsh Vardhan became the main rulers, but Chandelas were the first ruler who constructed with the capital of the region of Chedis. (Majumdar, 1951, p.252) The Bundelas and Marathas can also be regarded in this sense. There was no fort without religious spots. The religious spots in the forts of Bundelkhand were the center of belief not only for royal families but also become the center of faith and reverence of general people. Therefore these sites have gained unique and peerless fame. The religious sites within the forts played an important role in preserving and recharging the cultural heritage up to the centuries in Bundelkhand. These became the cause of cultural and religious harmony between the royal families and general people. These religious centers always released the message of prayer, peace and wish of prosperity from the royal family. Many times these temples and other spots provided the faithful with links between the royal families and general people which resulted to be the cause of welfare rule in the region.