Singularities Vol-4-Issue-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIAN POETRY – 20 Century Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

th INDIAN POETRY – 20 Century Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. Part I : Early 20th Century Part II : Late 20th Century Early 20th Century Poetry Overview Poetry, the oldest, most entrenched and most respected genre in Indian literary tradition, had survived the challenges of the nineteenth century almost intact. Colonialism and Christianity did not substantially alter the writing of poetry, but the modernism of the early twentieth century did. We could say that Indian poetry in most languages reached modernity through two stages: first romanticism and then nationalism. Urdu, however, was something of an exception to this generalisation, in as much as its modernity was implicated in a romantic nostalgia for the past. Urdu Mohammad Iqbal Mohammad Iqbal (1877?-1938) was the last major Persian poet of South Asia and the most important Urdu poet of the twentieth century. A philosopher and politician, as well, he is considered the spiritual founder of Pakistan. His finely worked poems combine a glorification of the past, Sufi mysticism and passionate anti-imperialism. As an advocate of pan-Islam, at first he wrote in Persian (two important poems being ‗Shikwah,‘ 1909, and ‗Jawab-e-Shikwah,‘ 1912), but then switched to Urdu, with Bangri-Dara in 1924. In much of his later work, there is a tension between the mystical and the political, the two impulses that drove Urdu poetry in this period. Progressives The political came to dominate in the next phase of Urdu poetry, from the 1930s, when several poets formed what is called the ‗progressive movement.‘ Loosely connected, they nevertheless shared a tendency to favour social engagement over formal aesthetics. -

Contemporary Indian English Fiction Sanju Thoma

Ambedkar University Delhi Course Outline Monsoon Semester (August-December 2018) School: School of Letters Programme with title: MA English Semester to which offered: (II/ IV) Semester I and III Course Title: Contemporary Indian English Fiction Credits: 4 Credits Course Code: SOL2EN304 Type of Course: Compulsory No Cohort MA English Elective Yes Cohort MA other than English For SUS only (Mark an X for as many as appropriate): 1. Foundation (Compulsory) 2. Foundation (Elective) 3. Discipline (Compulsory) 4. Discipline (Elective) 5. Elective Course Coordinator and Team: Sanju Thomas Email of course coordinator: [email protected] Pre-requisites: None Aim: Indian English fiction has undeniably attained a grand stature among the literatures of the world. The post-Salman Rushdie era has brought in so much of commercial and critical success to Indian English fiction that it has spurred great ambition and prolific literary activities, with many Indians aspiring to write English fiction! Outside India, Indian English fiction is taken as representative writings from India, though at home the ‘Indianness’ of Indian English fiction is almost always questioned. A course in contemporary Indian English fiction will briefly review the history of Indian English fiction tracing it from its colonial origins to the postcolonial times to look at the latest trends, and how they paint the larger picture of India. Themes of nation, culture, politics, identity and gender will be taken up for in-depth analysis and discussions through representative texts. The aim will also be to understand and assess the cross-cultural impact of these writings. Brief description of modules/ Main modules: Module 1: What is Indian English Fiction? This module takes the students through a brief history of Indian English fiction, and also attempts to problematize the concept of Indian English fiction. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Vedanta and Cosmopolitanism in Contemporary Indian Poetry Subhasis Chattopadhyay

Vedanta and Cosmopolitanism in Contemporary Indian Poetry Subhasis Chattopadhyay illiam blake (1757–1827) burnt I have felt abandoned … into W B Yeats (1865–1939). A E I discovered pettiness in a gloating vaunting WHousman (1859–1936) absorbed both Of the past that had been predatory4 Blake and Yeats: The line ‘When I walked down meandering On the idle hill of summer, roads’ echoes Robert Louis Stevenson’s (1850– Sleepy with the flow of streams, 94) The Vagabond. Further glossing or annotation Far I hear the steady drummer of Fraser’s poems are not needed here and will Drumming like a noise in dreams … Far the calling bugles hollo, be done in a complete annotated edition of her High the screaming fife replies, poems by this author. The glossing or annotation Gay the files of scarlet follow: proves her absorption of literary influences, which Woman bore me, I will rise.1 she may herself not be aware of. A poet who does The dream-nature of all reality is important not suffer theanxiety of influence of great poets to note. This is Vedanta. True poetry reaffirms before her or him is not worth annotating. the truths of Vedanta from which arises cos- In ‘From Salisbury Crags’,5 she weaves myths mopolitanism. Neither the Cynics nor Martha as did Blake and Yeats before her.6 Housman too Nussbaum invented cosmopolitanism. This de- wove myths into his poetry. scription of hills and vales abound in Yeats’s2 and Mastery of imagery is essential for any poet. Housman’s poetry. Pride in being resilient is seen Poets may have agendas to grind. -

International Journal of the Frontiers of English Literature and the Patterns of ELT ISSN : 2320 - 2505

International Journal of The Frontiers of English Literature and The Patterns of ELT ISSN : 2320 - 2505 1 Page January 2013 www.englishjournal.mgit.ac.in Volume I, Issue 1 International Journal of The Frontiers of English Literature and The Patterns of ELT ISSN : 2320 - 2505 Another One Bites the Dark: Reading Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis as a Continuum of Aravind Adiga’s Dark India Exploration K. Koteshwar Research Scholar The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. e-mail : [email protected] Jeet Thayil’s first novel, Narcopolis is set mostly in Bombay in the 70s and 80s, and sets out to tell the city's secret history, when opium gave way to new cheap heroin. Thayil has said, he wrote the novel, “to create a kind of memorial, to inscribe certain names in stone”. As one of the characters (in Narcopolis) says, “it is only by repeating the names of the dead that we honor them. I wanted to honor the people I knew in the opium dens, the marginalized, the addicted and deranged, people who are routinely called the lowest of the low; and I wanted to make some record of a world that no longer exists, except within the pages of a book.” he told the Indian newspaper, The Hindu, that he had been an alcoholic (like many of the Bombay poets) and an addict for almost two decades: "I spent most of that time sitting in bars, getting very drunk, talking about writers and writing, and never writing. It was a colossal waste. I feel very fortunate that I got a second chance." Thayil has been writing poetry since his adolescence, paying careful attention to form. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Films 2018.Xlsx

List of feature films certified in 2018 Certified Type Of Film Certificate No. Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/Le (Video/Digita Producer Name Production House Type ngth l/Celluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH 1 LITTLE GANDHI VFL/1/68/2018-MUM 13 June 2018 91.38 Video HOUSE OF FILM - U ENGLISH SUBTITLE Assamese SVF 1 AMAZON ADVENTURE Assamese DIL/2/5/2018-KOL 02 January 2018 140 Digital Ravi Sharma ENTERTAINMENT UA PVT. LTD. TRILOKINATH India Stories Media XHOIXOBOTE 2 Assamese DIL/2/20/2018-MUM 18 January 2018 93.04 Digital CHANDRABHAN & Entertainment Pvt UA DHEMALITE. MALHOTRA Ltd AM TELEVISION 3 LILAR PORA LEILALOI Assamese DIL/2/1/2018-GUW 30 January 2018 97.09 Digital Sanjive Narain UA PVT LTD. A.R. 4 NIJANOR GAAN Assamese DIL/1/1/2018-GUW 12 March 2018 155.1 Digital Haider Alam Azad U INTERNATIONAL Ravindra Singh ANHAD STUDIO 5 RAKTABEEZ Assamese DIL/2/3/2018-GUW 08 May 2018 127.23 Digital UA Rajawat PVT.LTD. ASSAMESE WITH Gopendra Mohan SHIVAM 6 KAANEEN DIL/1/3/2018-GUW 09 May 2018 135 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das CREATION Ankita Das 7 TANDAB OF PANDAB Assamese DIL/1/4/2018-GUW 15 May 2018 150.41 Digital Arian Entertainment U Choudhury 8 KRODH Assamese DIL/3/1/2018-GUW 25 May 2018 100.36 Digital Manoj Baishya - A Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 9 HAPPY MOTHER'S DAY Assamese DIL/1/5/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 108.08 Digital U Chavan Society, India Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 10 GILLI GILLI ATTA Assamese DIL/1/6/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 85.17 Digital U Chavan Society, India SEEMA- THE UNTOLD ASSAMESE WITH AM TELEVISION 11 DIL/1/17/2018-GUW 25 June 2018 94.1 Digital Sanjive Narain U STORY ENGLISH SUBTITLES PVT LTD. -

Download Download

ASIATIC, VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2017 The Poetic Cosmos and Craftsmanship of a Bureaucrat Turned Poet: An Interview with Keki N. Daruwalla Goutam Karmakar1 National Institute of Technology Durgapur, India Keki Nasserwanji Daruwalla (1937-) occupies a distinctive position in the tradition of Indian English Poetry. The poet’s inimitable style, use of language and poetic ambience is fascinating. Daruwalla was born in pre-partition Lahore. His father Prof. N.C. Daruwalla moved to Junagadh, and later to Rampur and Ludhiana where the poet did his masters in English literature at Government College, Ludhiana (affiliated to Punjab University). In 1958, he joined the Indian Police Service and served the department remarkably well until 1974. An analyst of International relations in the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), he retired as Secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat and as Chairman JIC (Joint 1 Goutam Karmakar is currently pursuing his PhD in English at the National Institute of Technology Durgapur, India. He is a bilingual writer and his articles and research papers have been published in many International Journals. He has contributed papers in several edited books on Indian English literature. Email: [email protected]. Asiatic, Vol. 11, No. 1, June 2017 250 Goutam Karmakar Intelligence Committee). In 1970, he published his first volume of poetry Under Orion and has subsequently published several more: Apparition in April (1971), Crossing of Rivers (1976), Winter Poems (1980), The Keeper of the Dead (1982), Landscapes (1987), A Summer of Tigers (1995), Night River (2000), Map Maker (2002), The Scarecrow and the Ghost (2004), Collected Poems 1970-2005 (2006), The Glass blower – Selected Poems (2008) and Fire Altar: Poems on the Persians and the Greeks (2013). -

7.The Scheme, Syllabus and Model Question Papers Rf Bachelor of Multi Media & Communication(B.M.M.C.) Programme (CBCSS-OBE) W.E.I 2020, Ar

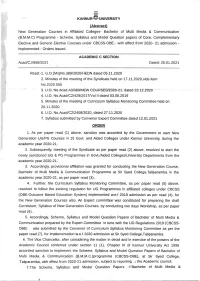

ftra. KANNURryAUNIVERSITY (Abstract) New Generation Courses in Atfiliated Colleges- Bachelor of Multi Media & Communication (B.M.M.C) Programme - Scheme, Syllabus and Model Question papers of Core, Complementary Elective and Generic Elective Courses under CBCSS-OBE - with effect from 2O2O- 27 admission - implemented - Orders issued. ACADEMIC C SECTION AcadlCLl8581202l Daled: 25.07.2o2L Read:-1. G.O.(Ms)No.389/2020/HEDN dated 05.11.2020 2. Minutes of the meeting of the Syndicate held on 17.11.2020,vide item No.2020.550 3. U.O. NO.Acad.A3/389/NEW COURSES/2020-2I,', dared 23.L2:2020 4. U.O. No.Acad 1C2142912077 Nol ll dared 03.06.2019 5. Minutes of the meeting of Curriculum Syllabus Monitoring Committee held on 20.LL.2020 6. U. O. No.Acad I Czl 24081 2O2O, date d 27 . LL.ZO2O 7. Syllabus submitted by Convenor Expert Committee dated 12.OL.2O2L ORDER 1. As per paper read (1) above, sanction was accorded by the Government to start New Generation UG/PG Courses in 15 Govt. and Aided Colleges under Kannur University, during the academic yeat 2O2O-27. 2. Subsequently, meetlng of the Syndicate as per paper read (2) above, resolved to start the newly sanctioned UG & PG Programmes in Govt./Aided Colleges/University Depa(ments from the academic yeat 2O2O-2!. 3. Accordingly, provisional affiliation was granted for conducting the New Generation Course, Bachelor of Multi Media & Communication Programme at Sir Syed College,Taliparamba in the academic year 2O2O-2t, as per paper read (3). 4. Further, the Curriculum Syllabus Monitoring Committee, as per paper read (5) above, resolved to follow the existing regulation for UG Programmes in affiliated colleges under CBCSS (OBE-Outcome Based Education System) implemented w.e.f 2019 admission as per read (4), for the New Generation Courses also. -

12Th Pune International Film Festival (09Th - 16Th January 2014 ) SR

12th Pune International Film Festival (09th - 16th january 2014 ) SR. NO. TITLE RUNTIME YEAR DIRECTOR COUNTRY OPENING FILM 1 Ana Arabia Ana Arabia 81 2013 Amos Gitai Israel, France AWARDEES FILM 1 Jait Re Jait Win, Win 116 1977 JABBAR PATEL INDIA 2 Swayamvaram One's Own Choice 131 1973 ADOOR GOPALKRISHNAN INDIA 3 Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Muqaddar Ka Sikandar 189 1978 PRAKASH MEHRA INDIA WORLD COMPETITION 1 Das Wochenende The Weekend 97 2012 Nina Grosse Germany 2 DZIEWCZYNA Z SZAFY The Girl From The Wardrobe 89 2012 Bodo Kox Poland 3 I Corpi Estranei Foreign Bodies 102 2013 Mirko Locatelli Italy 4 Mr. Morgan's Last Love Mr. Morgan's Last Love 116 2013 Sandra Nettelbeck Germany, Belgium 5 Thian Zhu Ding A Touch of Sin 129 2013 Zhangke Jia China, Japan 6 Night Train to Lisbon Night Train to Lisbon 110 2013 Bille August Germany, Portugal, Switzerland 7 La Pasión de Michelangelo The Passion of Michelangelo 97 2012 Esteban Larraín Chile, France, Argentina 8 Dom s Bashenkoy House with Turret 111 2012 Eva Neymann Poland Joanna Kos-Krauze, Krzysztof 9 Papusza Papusza 131 2013 Poland Krauze 10 Buqälämun Chameleon 73 2013 Ru Hasanov, Elvin Adigozel Azerbaijan, France, Russia 11 Rosie Rosie 106 2013 Marcel Gisler Switzerland, Germany 12 Queen of Montreuil Queen of Montreuil 87 2012 Solveig Anspach France 13 Fasle Kargadan Rhino Season 88 2012 Bahman Ghobadi Iraq, Turkey 14 Kanyaka Talkies Virgin Talkies 115 2013 K.R. Manoj India MARATHI COMPETITION 1 72 Miles Ek Pravas 72 Miles Ek Pravas 96 2013 Rajeev Patil INDIA Sumitra Bhave,Sunil 2 Astu So Beit 123 -

Media in Kerala

MEDIA IN KERALA THIRUVANANTHAPURAM MEDIA IN KERALA THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Print Media STD CODE: 0471 Chandrika .................................... 3018392, ‘93, ‘94, 3070100,101,102 Kosalam, TC -25/2029(1) Dharmalayam Road, Thampanoor, Thiruvananthapuram. Fax ................................................................................... 2330694 Email ................................................... [email protected] Shri. C V. Sreejith (Bureau Chief) .............................. 9895842919 Shri. K.Anas (Reporter) ............................................. 9447500569 Shri. Sinu .S.P.Kurup (Reporter) ............................ 0472-2857157 Shri. Firdous Thaha (Reporter) .................................. 9895643595 Shri. K.R.Rakesh (Reporter) ...................................... 9744021782 Shri. Jitha Kanakambaran (Reporter) ......................... 9447765483 Shri. Arun P Sudhakaran (Sub-editor) ........................ 9745827659 Shri. K Sasi (Chief Photographer) .............................. 9446441416 Daily Thanthi ........................................................................... 2320042 T.C.42/824/4,Anandsai bldg.,2nd floor,thycaud ,Tvm-14 Email ......................................................... [email protected] Shri.S.Jesu Denison(Staff Reporter) ............................ 9847424238 Deccan Chronicle .......................................................... 2735105, 06, 07 St. Joseph Press Building, Cotton Hills, Thycaud P.O., Thiruvananthapuram -14 Email .......................................................... -

Research Paper Literature Margins of Mumbai: a Study on Representation of Margin in Jeet Thayil’S Narcopolis

Volume-3, Issue-11, Nov-2014 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Research Paper Literature Margins of Mumbai: a Study on Representation of Margin in Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis Veena S M.A English and Comparative Literature ABSTRACT The study tries to analyze the representation of minority in Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis against the tradition of Bombay novels. It performs a thematic study on the novel and also the representation of the androgynous protagonist. KEYWORDS : Bombay Novels, Minority, Eunuch, Androgynous protagonist, Opium, Opium dens and Addiction “Bombay was central, had been so from the moment of its creation: castrated resulting in her erasure of distinct sexual identity and con- the bastard child of a Portuguese English wedding, and yet the most sequently addiction to opium. She works for her husband Rashid who Indian of Indian cities . all rivers flowed into its human sea. It was is also the den owner. an ocean of stories; we were all its narrators and everybody talked at once.” (Rushdie 350) Other people whose lives centers around opium include Salim, a co- caine peddler who is brutally sodomized by his master; Newton Xavi- Starting from the Midnight’s Children and The Moor’s Last Sigh, er, a famous artist and junkie drunk and Mr. Lee a Chinese drug deal- the city has become the setting of several novels in English owing er who initiates Dimple towards opium. It also deal with two kind of to its cultural, social and ethnic diversities that form a conglomerate. people put together in the same society – the one with choices and It was followed by a number of novels of Rohinton Mistry (Such A the one without them (Ahrestani 2) While Dimple, Salim and Mr.